5.4 Decolonizing the Canadian Workplace

Tricia Nicola Hylton

“Colonialization as a system [did] not go away, it remains”

(Decolonisation, 2023)

One of the many misconceptions about colonization is that it ended when colonizing powers departed occupied lands. However, in Decolonisation (2023), Dr. Ndlovu-Gatsheni explained that the departure of colonial powers from occupied lands only signified the “end of colonization as an event” (2:45), not of colonialism as a system. Colonialism was not simply the occupation of land and the stealing of resources. Colonialism also involved instituting the colonial worldview: the process of replacing the values, beliefs, economic, political, and educational systems of Indigenous populations with those of the colonizing nation (Deconlonisation, 2023; Wilson & Hodgson, 2017). Dr. Ebalaroza-Tunnell (2024) states, “Colonialism wasn’t just about physical land grabs; it also imposed dominant ideologies and systems of knowledge…that prioritized Eurocentric viewpoints, hierarchical structures, and an “extractive” approach to work” (para. 7).

For persons and nations once colonized, the colonial worldview has resulted in many detrimental effects. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (n.d.) and the United Nations High Commission (2023) argue that the cause of modern-day discrimination, inequality, and injustice is rooted in colonialism. Specifically, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (n.d.) states that a direct connection exists between colonialism and

- contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, and xenophobia, and

- intolerance faced by Africans, people of African descent, people of Asian descent, and Indigenous Peoples.

In addition, The United Nations High Commission (2023) adds the following groups to those negatively impacted by the colonial worldview:

- persons of diverse sexual orientations,

- persons of diverse gender identities and expressions and/or sex characteristics, and

- women and children.

This understanding of colonization is important when discussing decolonization. Introduced in Unit 5.1: Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion: Terminology, decolonization involves a very intricate and complex process of breaking down the ideologies, systems, and structures established by the colonial worldview, and normalized over time, to establish new ideologies, systems, and structures (Decolonisation, 2023). This Unit does not propose to examine the full breadth of issues associated with decolonization. Instead, this Unit will take a specific look at decolonization as a strategy to deconstruct the ideologies, systems, and structures that exist in the Canadian work environment.

The Colonial Worldview and Its Impact

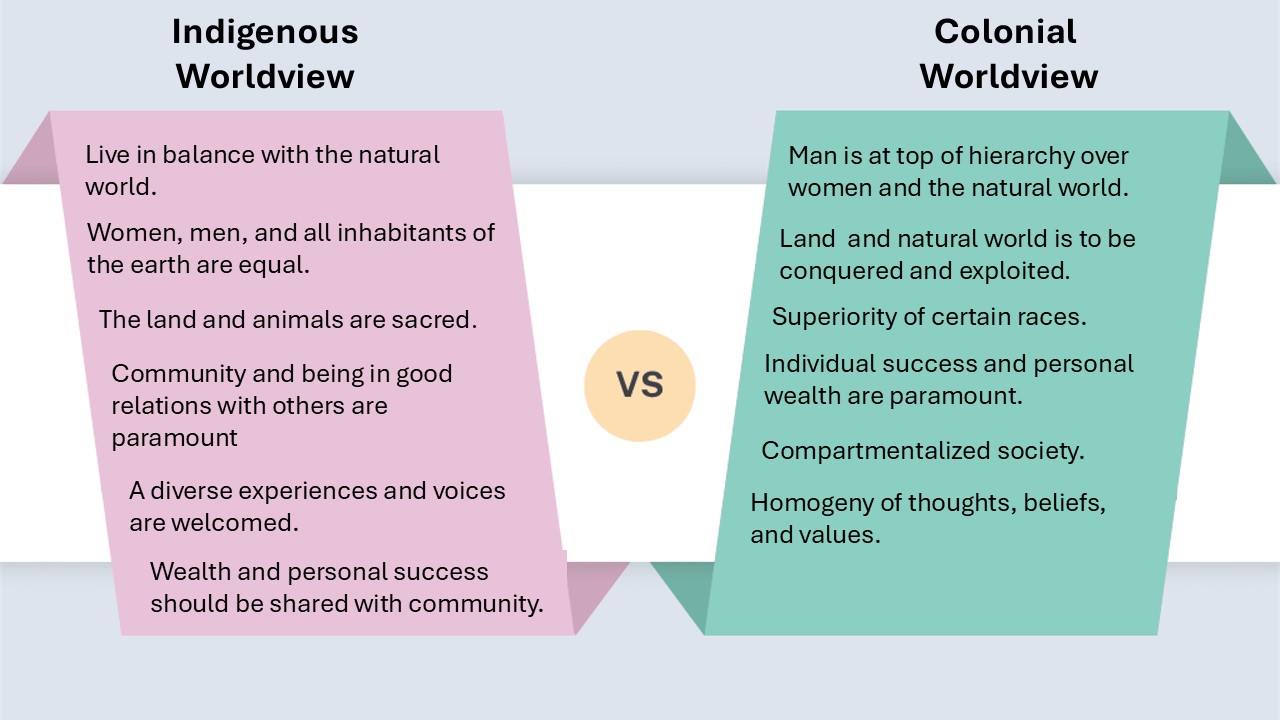

We’ll begin our discussion by examining the characteristics of the colonial worldview and how these characteristics materialize in the Canadian work environment. Common characteristics of the colonial worldview include:

- Valuing individualism and competition and seeking success for oneself above all else,

- Believing the environment and its resources can be owned and exploited for the accumulation of wealth and personal enjoyment,

- Instituting a hierarchical order in society that declares some (e.g. men) as more important, powerful, and influential than others (e.g. women),

- Placing importance on the accumulation of material things as a symbol of status and power, and

- Acknowledging only one correct view of the world.

(Intercultural Communications, n.d.; Wilson & Hodgson, 2018; Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc. 2016; Ermine, 2007).

Case Study 1 provides two examples of how these characteristics are experienced in the Canadian workplace by members of racialized and marginalized groups.

Case Study 1: The Canadian Public Service

According to the Canadian Encyclopedia (2013), the Canadian Public Service supports the development and administration of government services such as healthcare, national defence, and justice. Those within the Public Service act as agents of the presiding government, elected officials, and governmental departments. In this role, the Public Service is a reflection and representative of Canadian values. The following two examples detail the experience of two racialized and marginalized groups employed in Canada’s Public Service.

Example 1:

The Black Executives Network (BEN), a support group of Black executives working in the federal Public Service, released a report in November 2024 based on interviews with 100 current and former Black Public Service executives. The report detailed the experience of systemic racism endured by former and current members of the BEN in the Public Service. Some of the more disturbing findings in the report include:

- being called the N-word

- being threatened with physical violence,

- being denied career advancement opportunities,

- enduring instances of workplace harassment and intimidation,

- encountering threats of reputational harm, and

- having the merit of professional credentials, experience, and position questioned and/or undermined.

(CBCNews, 2024)

Example 2:

The report, Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation (2017), details the experiences, barriers, and challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples working in the Public Service. Based on 2,100 responses from current and former Indigenous Public Service employees, the following are some the more important challenges and barriers encountered:

- undervaluing of experience and expertise,

being denied career advancement and promotion opportunities,

being denied career advancement and promotion opportunities,- experiencing unfair and inaccessible hiring practices,

- enduring general harassment and discrimination practices, and

- combatting lack of respect for Indigenous cultures.

Of note, the report also found that Indigenous employees reported significantly higher levels of harassment and discrimination than non-Indigenous employees and that only 3.7% of senior positions in the Canadian Public Service were held by an Indigenous Person (Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation, 2017).

The experiences of Black executives and Indigenous employees in Canada’s Public Service are disturbing, and should be. The importance of these negative interactions occurring in Canada’s largest single employer (CBCNews, 2024) cannot be overstated. However, as untenable as these practices are, the question that must be asked and answered is do these practices embody the characteristics of the colonial worldview?

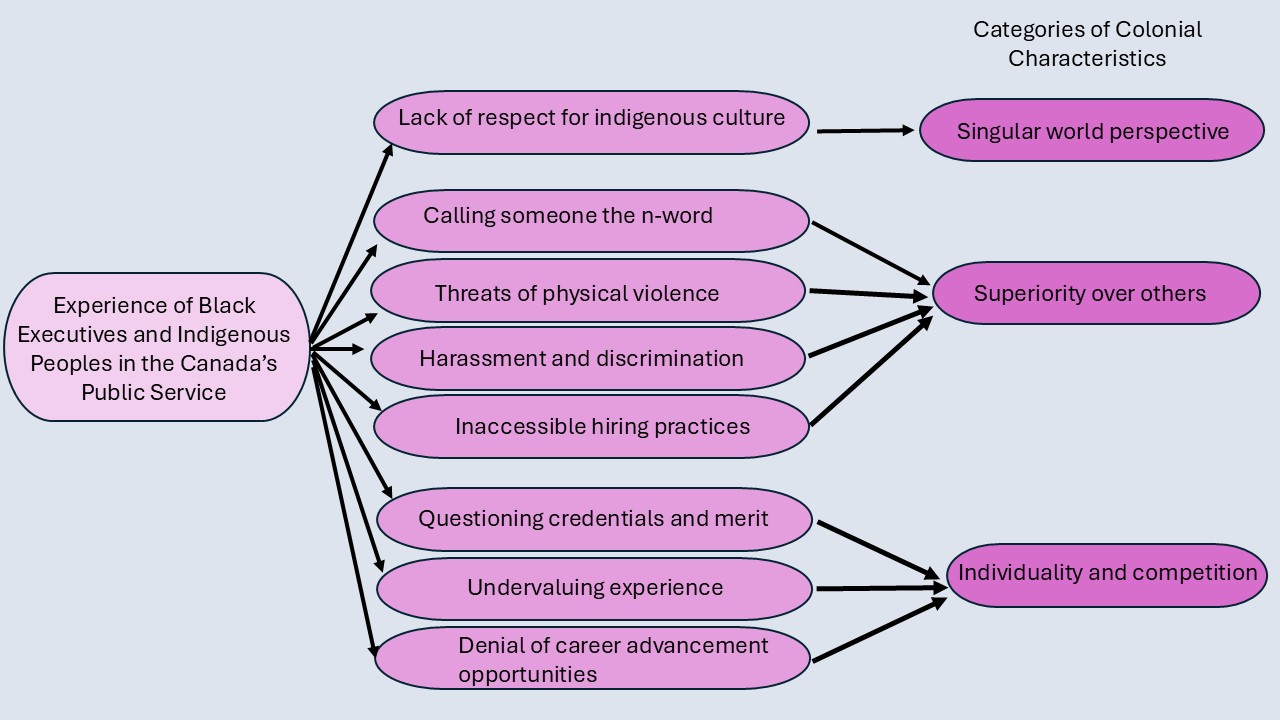

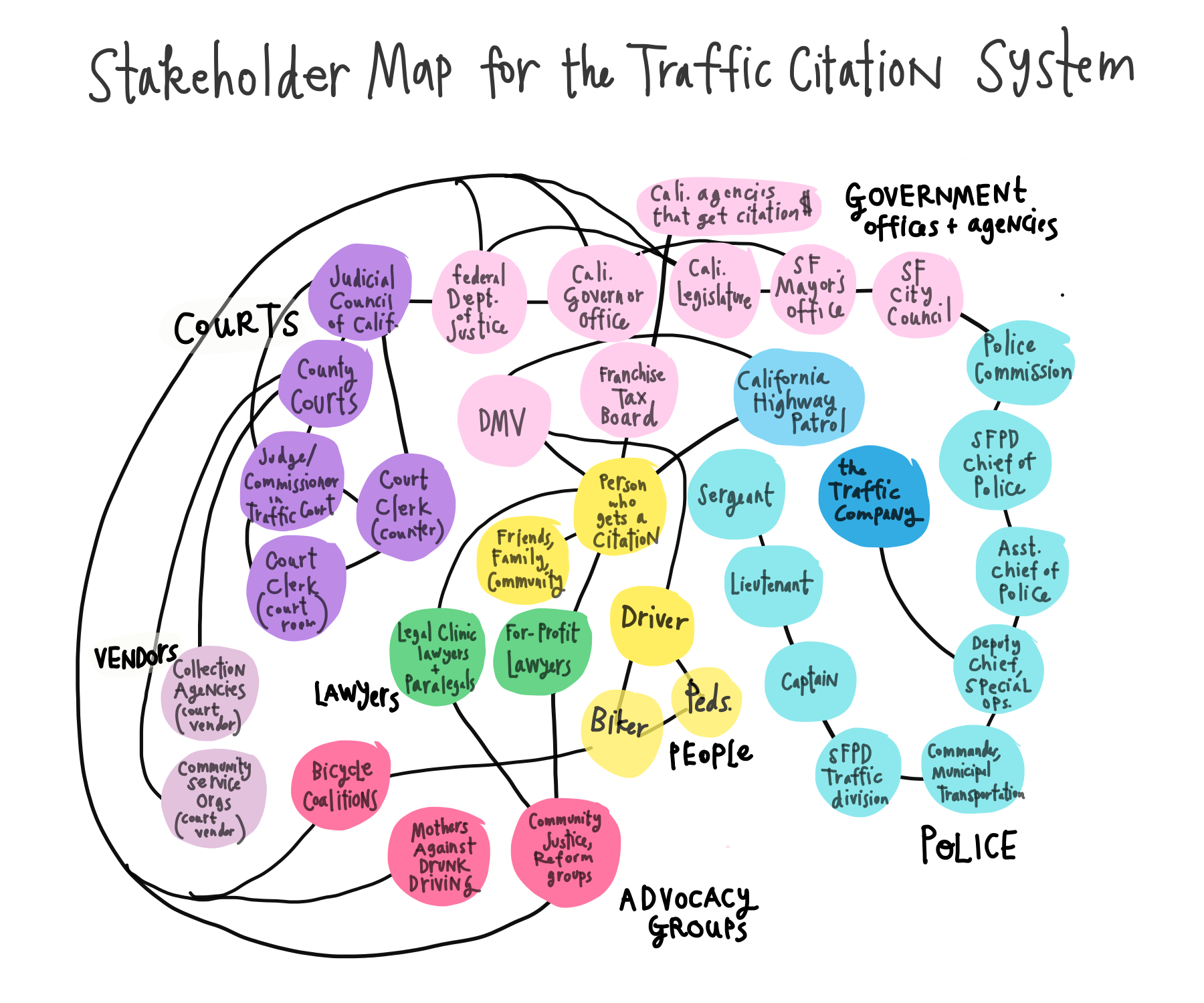

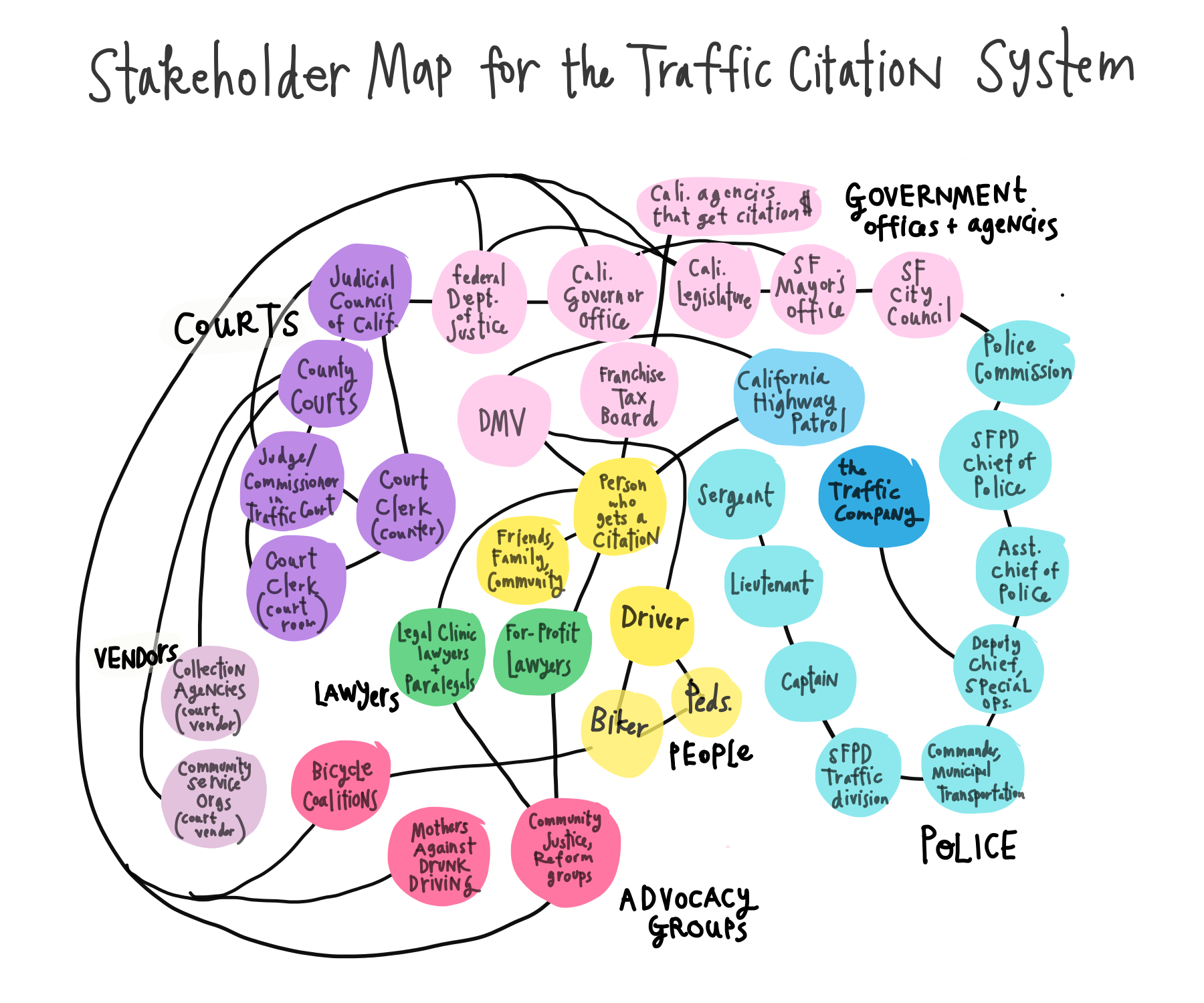

One measurement to answer this question is to assess the noted negative behaviours towards Black executives and Indigenous Public Service employees against the characteristics of the colonial worldview described above (Intercultural Communications, n.d.; Wilson & Hodgson, 2018; Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc. 2016). An analysis of Figure 14.1 reveals that the treatment of Black executives and Indigenous employees fall under three categories of the colonial worldview: adherence to a singular worldview, acceptance of the notion that some are superior to others, and validation of individualism and competition.

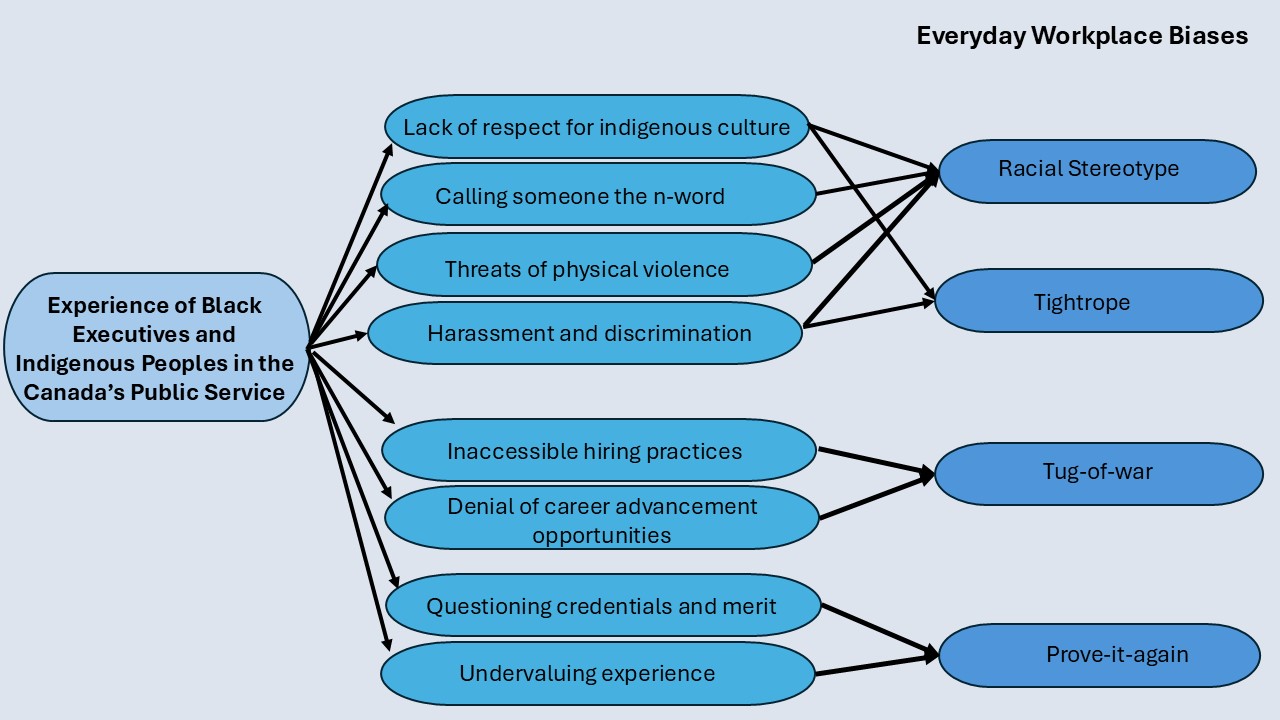

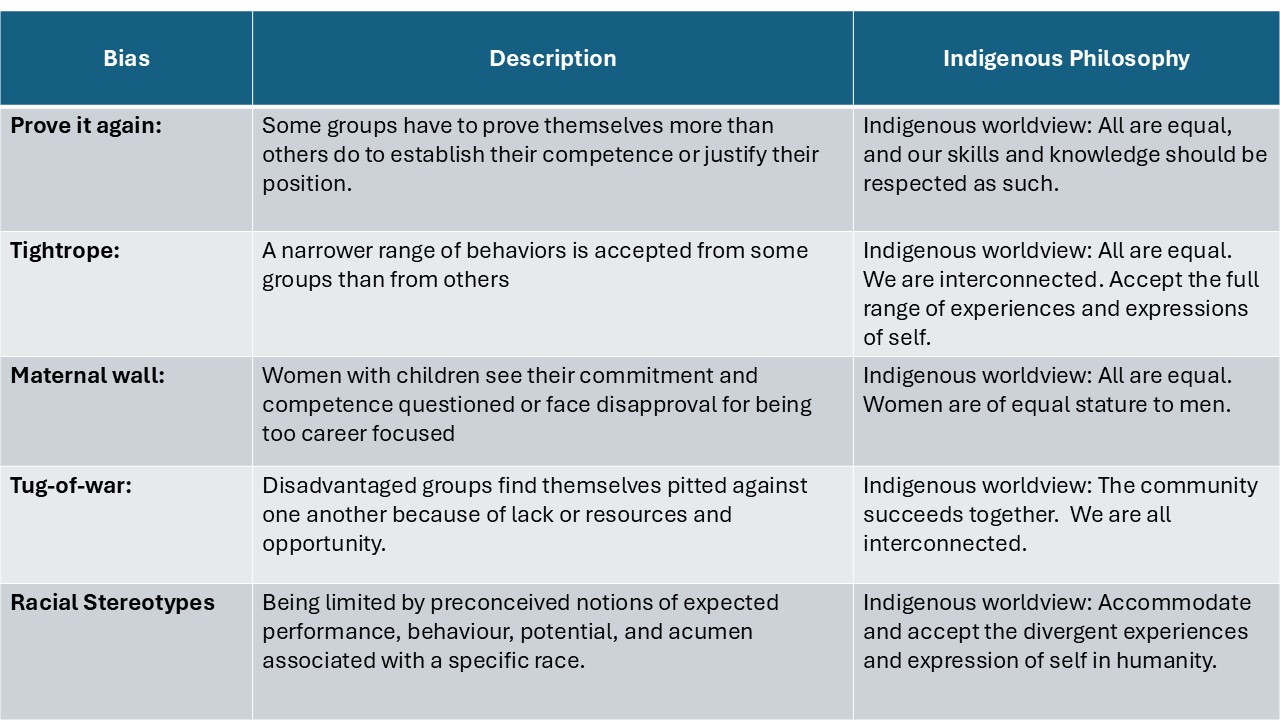

A second measurement to answer the question: do the practices towards Black executives and Indigenous Public Service employees embody the characteristics of the colonial worldview was introduced in Unit 5.2: EDI in the Canadian Workplace. There, Williams (2020) offers the finding of a 10-year study that identified five patterns of bias experienced in everyday business interactions: the tightrope bias, the maternal wall bias, the racial stereotype bias, the tug-of-war bias, and the prove-it-again bias . An examination of Figure 5.4.2 reveals the treatment of Black executives and Indigenous Public Service employees reflects four of the biases identified: the prove-it-again bias, racial stereotype bias, the tug-of-war bias, and the tightrope bias.

Although Case Study 1 highlights the actions of those within Canada’s Public Service, there is a case to be made for the broad scale existence of the colonial worldview in business structures and systems across this country. Ironically, the case is made by the existence of equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) policies. As we will discuss, there would be no need for EDI policies and initiatives if current business systems and structures were not rooted in the colonial worldview.

Exercise: Reader Reflection

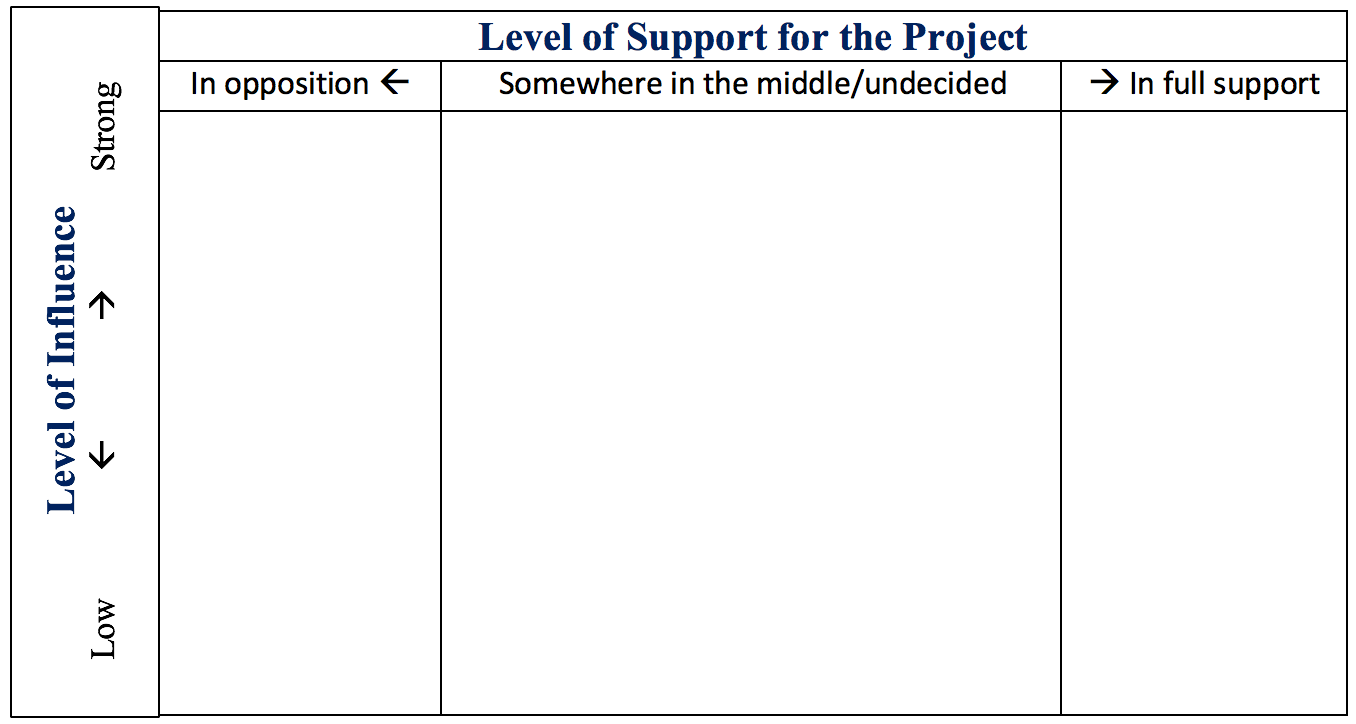

Use the template below to plot the practices experienced or observed in a past or current workplace against the characteristics of the colonial worldview and the five patterns of everyday business biases.

EDI and the Colonial Worldview

Figures 5.4.1 and 5.4.2 reveal that the colonial worldview is alive and well in Canada’s largest employer. The harmful behaviours discussed in Case Study 1 demonstrate what scholars refer to as the the invisible, broadly accepted, and unchallenged existence of colonial values and beliefs (Decolonisation, 2023; Ermine, 2007; Sue, 2021; Sue et al., 2020) that continue to inform, influence, and affect everyday interactions. Ermine (2007) explains the phenomenon this way:

This notion of universality remains simmering, unchecked, enfolded as it is, in the subconscious of the masses and recreated from the archives of knowledge and systems, rules and values of colonialism that in turn wills into being the intellectual, political, economic, cultural, and social systems and institutions of this country (p. 198).

In the business context, policies introduced to remedy the adverse impacts of the colonial worldview are classified under the banner of EDI. Golden (2024) notes, the genesis of EDI policies is rooted in “a time when societal movements and legal changes began to reshape the corporate world” (para. 2) to balance recognized inequities in business structures and systems. Taking shape during the 1960s (Golden, 2024), initially EDI policies focused on redressing racial and gender inequality. However, by the 1990s, EDI policies “began to recognize and address the diverse needs of various identity groups, including ethnic, religious, and LGBTQ+ communities” (Golden, 2024, para. 11).

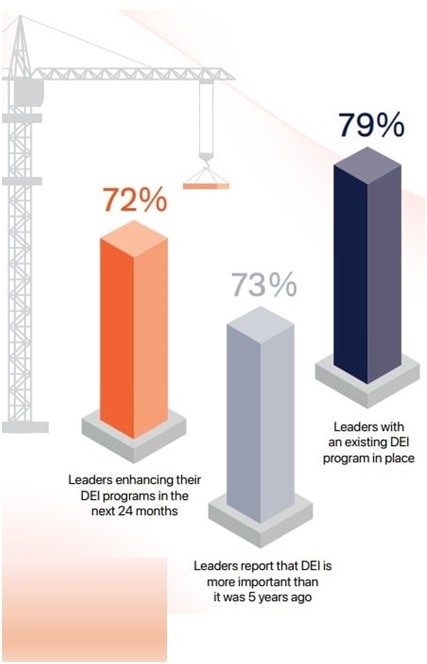

Today, 60+ years after the first EDI policies were introduced (Golden, 2024), as demonstrated by Case Study 1, the inequities that existed in business structures and systems are not yet balanced. In fact, several recent reports on the state of EDI in business reveal that, both domestically and internationally, businesses continue to support existing EDI policies and plan to increase their financial commitments to EDI policies in coming years as a strategy to address continued and ongoing inequities in the workplace (Benefits Canada, 2023; Carufel, 2024; Workday, 2024). The following statistics and Figure 5.4.3 illustrate this finding:

-

Figure 5.4.3 reveals the perspective of business leaders on the importance of EDI initiatives (Carufel, 2024). In 2023, 72% of Canadian business leaders increased financial support of EDI policies and initiatives (Benefits Canada, 2023).

- In 2024, a survey of 2,600 global business leaders found that 78% believed EDI policies had risen in importance and planned on increasing their organization’s EDI budget (Workday, 2024).

- In 2024, a survey of over 400 executives in mid-to-large U.S. companies reported that

- 79% of respondents confirmed the existence of EDI policies at their firm,

- 78% of respondents planned on increasing the support for EDI policies over the next two years, and

- 73% of respondents believed the importance of EDI policies had grown over the last five years.

(Carufel, 2024).

These statistics, among others, are an indication that the invisible and broadly accepted ideologies of the colonial worldview (Decolonisation, 2023; Ermine, 2007; Sue, 2021; Sue et al., 2020) are present in our modern workspaces. A problem that does not exist, does not need a solution. Workspaces that are diverse, equitable, and inclusive do not need EDI policies to balance the playing field. The continued and growing need of EDI policies confirms the broad scale influence of the colonial worldview in business systems and structures and the continued and growing need for strategies to counteract and temper that influence.

What can be done to decolonize ‘workplaces into spaces where knowledge is democratized, power is shared, and equity thrives” (Ebalaroza-Tunnell, 2024, para. 2)? The remainder of this Unit will examine this question from a structural and individual perspective.

Decolonizing Business Systems and Structures: An Indigenous Perspective

Can equity, diversity, and inclusion truly happen within business systems and structures founded on hierarchy, dominance, exploitation, and authority? Can a system meant to benefit some and not others create an inclusive playing field where everyone can thrive? Williams (2020) answers these questions with a resounding no: “To address structural [inequity], you need to change structures…we need to fix the business system” (1:10).

Changing society’s structures and systems will require a massive, intentional, and sustained ideological shift away from the established values and beliefs of the colonial worldview towards the values and beliefs of an alternative worldview. This ideological shift, at its essence, is the process of decolonization (Decolonisation, 2023). Ermine (2007) writes that in order “to redesign social systems[,] we need…[to] accept that a monoculture with a claim to one model of humanity and one model of society” (p. 198) is a fallacy. Such an ideological shift would reshape social systems to reflect the beliefs and values of the alternative worldview, and specifically for the purpose of this discussion, reshape business systems and structures in a similar manner.

According to Kouri-Towe and Martel-Perry (2024) decolonization can be examined through two alternative worldviews: the Indigenous and Afro-centric worldviews. In addition, decolonization can also be examined through a number of individual approaches, including gender equality, sexual equality, racial equality, and environmental equality. This Unit will examine the process and impacts of decolonization through the lens of the Indigenous worldview. The University of Alberta (n.d.) explains the Indigenous worldview this way:

Indigenous Ways of Knowing are based on the idea that individuals are trained to understand their environment according to teachings found in stories. These teachings are developed specifically to describe the collective lived experiences and date back thousands of years. The collective experience is made-up of thousands of individual experiences. And these experiences come directly from the land and help shape the codes of conduct for indigenous societies. A key principle is to live in balance and maintain peaceful internal and external relations. This is linked to the understanding that we are all connected to each other. The hierarchical structure of Western world views that places humans on the top of the pyramid does not exist. The interdependency with all things promotes a sense of responsibility and accountability. The people would respond to the ecological rhythms and patterns of the land in order to live in harmony. (00:30).

Continue learning about the Indigenous worldview and how it differs from the colonial worldview by viewing the full video, World View.

Rose (2021) suggests that in many ways, the Indigenous worldview offers an opposing philosophy on how to interact with and value the world we live in. The author offers that integral to the Indigenous worldview is the understanding that “all living things are connected…contribute to the circle of life equally and should be acknowledged and respected as such” (3:27). Review figure 5.4.4 for differences in characteristics between the Indigenous worldview to those of the colonial worldview.

Figure 5.4.4 illustrates quite a few differences in the belief and value systems of the colonial and Indigenous worldviews. Of note are

- a shift away from a singular worldview to a worldview that is inclusive of diverse experiences and voices,

- a shift away from superiority of some over others to equality and balance for all,

- a shift away from competition to collaboration and cooperation,

- a shift away from individualism to collectivism and community, and

- a shift away from exploiting resources to honouring and safeguarding them.

These shifts are not superficial. They suggest a fundamental rewiring of the way we think about and interact with each other and our environment. Central to our conversation is the possibility of applying the Indigenous worldview as a vehicle to decolonize the workplace. Let’s examine this possibility further.

Equality: The Indigenous worldview does not include a hierarchical structure that places one race over another, men over women, or humans over nature. Thus, the Indigenous worldview embedded with the philosophy of equality could create work environments that

- respect the skills and contributions of all employees equally,

- are stewards of the land, animals, and other natural resources, and

- welcome the skills and contribution of all employees at all levels of operation.

Variation: The Indigenous worldview acknowledges and welcomes the diversity that exists within humanity. The Indigenous worldview embedded with the philosophy of variation could result in work environments that promote

- innovative, collaborative, and democratic, and

- empathetic, supportive, and inclusive

Community/interconnectedness: Being in good relations with your community is at the heart of the Indigenous worldview (Rose, 2021). A work culture embedded with this value could result in work environments that

- do not exploit workers,

- ensure a basic living wage,

- provide safe work environments,

- support a work-life balance, and

- employ sustainable business practices.

EXERCISE: Reader Reflection

The list presented above is not exhaustive as the Indigenous worldview would result in many other changes to work environments. Share your thoughts on what other changes you believe would result from the establishment of the Indigenous worldview in the workplace.

Another measure by which the Indigenous worldview can be assessed to evaluate its potential to decolonize the systems and structures that make up our work environment is the degree to which it avoids or prevents the five patterns of biases experienced in everyday business interactions (Williams, 2020). Table 5.4.1 presents each bias, its description, and how the Indigenous worldview is likely to impact their occurrence in the workplace.

Table 5.4.1 How Indigenous Worldview Can Change Five Types of Bias

EDI and the Indigenous Worldview

An important observation when reviewing the potential results of implementing the Indigenous worldview in business structures and systems is the organic occurrence of behaviours and practices that are typically considered the outcome of EDI policies and initiatives. Aspects of equity, diversity, and inclusion are not planned, legislated, or imposed under the Indigenous worldview. Instead, practices that are currently the result of EDI policies naturally occur, directly connect, and are enmeshed with the Indigenous worldview.

The possibilities above of an alternative way of doing and thinking in the many workspaces across this country is not imagery or hypothetical. Work environments that reflect the principles of the Indigenous worldview already exist. The following case study of Sanala Planning, an Indigenous owned and run business, is one example of the Indigenous worldview in action.

Case Study 2: Sanala Planning

Originally Alderhill Planning, Sanala Planning is based in Kamloops, BC. and is owned and run by Jessie Hemphill, a member of the Sqilxw People (Sanala, n.d.). Founded in 2016, the company’s mandate is to “work with governments, businesses and First Nations communities to support organizational development, providing everything from trauma-informed facilitation to comprehensive community plans, to workshops on reconciliation and decolonization” (Kilawna, 2022, para. 4). Through community consultations, a bottom-up approach was utilized to ensure the company’s business plan, mission, and activities aligned with the needs and wants of the communities served by the organization.

A first business practice to be highlighted here is one that is not typically associated with the business environment: empathy. Hemphill says this trait contributes to “a really safe [and] nurturing place to work” (Kilawna, 2022, para. 30). Allowing staff members to breast feed during Zoom meetings, designating office space for spiritual practice, and giving employees the flexibility to openly acknowledge and share mental health challenges (Kilawna, 2022) are some of practices that support this trait. Other alternative business practices employed by Sanala Planning include

- a non-hierarchical and inclusive decision-making process with employees,

- a shortened work week (4 days/week), and

- reduced daily work hours.

(Kilawna, 2022).

Many aspects of the Indigenous worldview can be observed in the creation and day-to-day business practices of Sanala Planning: community engagement, collaboration, work-life balance, empathy, and a democratic power structure. Of significance is the understanding that these practices have not undermined Salana Planning’s ability to be financially successful. According to Kilawna (2022), Sanala Planning has a market value of $2 million.

Although, businesses like Sanala Planning exist, businesses established to reflect the Indigenous worldview are not commonplace. However, opportunity exists to integrate Indigenous values and beliefs into business systems and structures. Ermine (2007), Fielding News (2022), and Egale Canada (2024) offer the following strategies to accomplish this goal:

- Do your research to continue learning the histories, teachings, practices, beliefs and values of Indigenous Peoples.

- Challenge your own understanding and acceptance of current business systems and structures. Do the hard work necessary to bring to light many of the unchallenged values and beliefs that form the basis of current business systems and structures.

- Advocate for the Indigenization of workplace practices by using your knowledge of the Indigenous worldview to promote an ideological shift in workplace practices.

- Promote the establishment of physical spaces that create communal connection and spiritual awareness.

Exercise: Reader Reflection

Compare the business practices of Sanala Planning to an organization/business that you currently work for or previously worked for. Reflect on the differences and similarities between the two organizations. How do you think these differences and similarities affect or affected the work environment?

Decolonizing Organizational Structure: Individual Action

Systemic and structural change in the workplace will undoubtedly take time. In the meantime, there is much you can do on an individual level to decolonize your current and future work environments for all equity seeking groups.

1. Allyship

The concept of allyship was introduced in Unit 5.1: Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion: Terminology. There, an ally is defined as a person who supports equity seeking persons or groups through action by interrupting behaviours and situations counter to fairness and equality (para. 34). Working with this definition, Ravishankar (2023) offers the following strategies to help recognize and disrupt patterns of inequity in the workspace:

- Learn about the stereotypes, experiences, and identities of the marginalized group you would like to support. Here the author suggests contacting different organizations that advocate for the rights of marginalized groups. If you are interested in supporting one particular group or notice specific harmful behaviours in your workplace that you would like to address, speak directly to those affected to understand how best to lend your support.

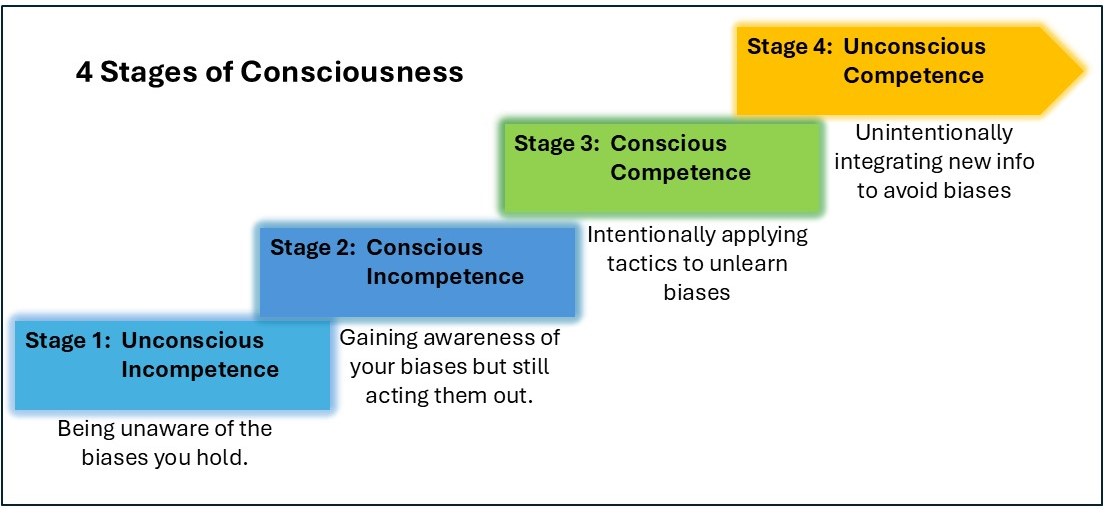

- Unlearn your own personal biases. We all carry some biases, many of which may be unconscious. Biases are products of our worldview. Reflect on your own behaviours and thoughts to make the unconscious, conscious. When you better understand the bias you hold, you can address them and begin your journey towards allyship. Review Figure 5.4.5 for a model of how to work your way from being unaware of your own biases towards conscious awareness and action.

- Voice your opposition to instances of microaggressions, discrimination, racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, etc. when you witness these behaviours in the work environment. The author notes that saying something “as simple as “Not cool,” or “That’s not funny”” (para. 17) is suitable when you encounter such behaviours at work.

- Model the behaviour you would like to see in your workplace. By treating people appropriately, you can provide an example for others of how to interact respectfully with diverse members or your work environment. The author suggests that the use of inclusive language (see 3.2) is one way to model behaviour of how to treat others respectfully.

The publication, Skoden (2022), includes the Ally Bill of Responsibilities developed by Dr. Lynn Gehl. Developed from an Indigenous perspective, the Ally Bill of Responsibilities provides an extensive list of what it means to be a responsible ally.

2. Be Curious, Take Accountability, and Unlearn to Relearn

In the TedX Talk, Deconlonizing the Workforce (2024), the speaker, Toni Lowe, offers three tactics that can further help decolonize the workforce.

Strategy 1: Be curious. Lowe (2024) offers that when certain dynamics occur in the workplace, you have a responsibility to investigate the reason for the observed behaviour, thought, or action. For example, Case Study 1 revealed that Indigenous Public Service employees were asked to complete IQ tests that non-Indigenous employees were not (Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation, 2017). Thus, when similar situations occur in your workplace, Lowe (2024) encourages you to become curious and ask questions like:

- What is happening?

- Why is this happening?

- What belief forms the basis for this action?

- Do I believe this?

- Is this true?

- What else do I believe that may not be true?

The answers to questions like these, the author suggests, may lead to a new awareness of inequities in your work environment.

Step 2: Take accountability. Reflect on your role in the current system. Consider if your “silence, complacency, or advantage” (Lowe, 2024) props-up or confronts the status quo. The author explains that reflecting on your role in the system is the first step towards taking accountability for your actions or inactions, acknowledging the lived experience of racialized and marginalized groups, and embracing your power to influence your environment.

Step 3: Unlearn to Re-learn. In agreement with Ravishankar (2023), Lowe (2024) also imparts the importance of recognizing and addressing unconscious biases. The author argues that in doing so, you will be able to clearly see your choice to stop participating in and supporting an outdated worldview that no longer makes sense for a modern world (Lowe, 2024).

3. Believe Lived Experiences. A simple but effective strategy to decolonize the workplace is based on a study on the effects of microaggression in the work environment. Sue (2021) concludes that an important aspect of decolonizing the work environment is for members of dominant groups to acknowledge and believe the lived experiences of maltreatment endured by racialized and marginalized colleagues. Although, the experience of racialized and marginalized groups is often very different from the experience of members of the dominant groups in the same work environment, the author encourages members of dominant groups to not ignore, deny, doubt, discredit, or minimize these lived experiences (Sue, 2021). Instead, Sue et al. (2019) directs individuals to

- Reaffirm and validate the lived experience of racialized and marginalized groups by believing their experiences,

- Be vocal and visible in your support for the fair treatment of every employee,

- Be vocal and visible in your opposition to the maltreatment of any employee, and

- Seek support from and mobilize with like minded employees to develop better workplace practices and policies.

Exercise: Reader Reflection

- Which of the individual decolonizing strategies above are you most comfortable integrating into your current and/or future workplace? Explain why.

- Can you think of other strategies that could also decolonize the workplace.

Colonialism and the colonial worldview are not issues of the past. Instead, the colonial worldview continues to affect all aspect of Canadian society, including our workspaces. The review of the practices within the Canadian Public Service demonstrated the colonial worldview at work by revealing discriminatory, racist, hostile and exclusionary treatment of Black and Indigenous employees. Such actions, however, are not confined to the Canadian Public Service. Instead, the continued existence and growing importance of EDI policies in our workspaces indicates the presence of continued inequities towards racialized and marginalized groups. A strategy to decolonize the workplace at the structural and systemic level was offered via the Indigenous worldview. Here, we saw that the Indigenous worldview provides an alternative to the recognized imbalances in current business structures and systems because of its capacity to create workspaces that organically reflect the principles of EDI. The example of Sanala Planning is offered as an illustration of the potential of the Indigenous worldview to create successful and financially profitable work environments. At the individual level, the Unit ends by speaking directly to you, the reader, whose role is central in creating decolonized workspaces. By adapting the individual actions discussed above, you can become agents of change in “paving a way for a workforce where everyone can thrive” (Lowe, 2024, 14:11).

References

Benefits Canada. (2023). 72% of business leaders increased investment in DEI over past year: survey. News. https://www.benefitscanada.com/news/bencan/72-of-business-leaders-increased-investment-in-dei-over-past-year-survey/

Beebe, S., Beebe, S., Ivy, D., & Watson, S. (2005). Communication principles for a lifetime (Canadian Edition). Pearson.

Carufel, R. (2024). Despite a year of attacks and criticism, business leaders continue to support DEI initiatives: New research examines DEI progress and today’s challenges. Agility PR solutions. Despite a year of attacks and criticism, business leaders continue to support DEI initiatives: New research examines DEI progress and today’s challenges – Agility PR Solutions

CGSMUS. (2023). Decolonisation [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Km_TmRuk7Q

Doerr, A. (2013). Public service. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/public-service

Ebalaroza-Tunnell, G. (2024). Decolonizing the workplace: Building a more equitable future. Medium. https://medium.com/@DrGerryEbalarozaTunnell/decolonizing-the-workplace-building-a-more-equitable-future-87022f903187

Egale Canada. (2024). Indigenous workbook. Building bridges. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://egale.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/2.-Indigenization-Workbook_Final.pdf

Ermine, W. (2007). The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal 6(1). https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ilj/issue/view/1822

Fielding News. (2022). Why making vital distinctions between Indigenous and dominant worldviews is not a “binary thinking problem”. Fielding Graduate University. https://www.fielding.edu/making-vital-distinctions-between-indigenous-and-dominant-worldviews/

Golden, H. (2024). History of DEI: The evolution of diversity training programs – NDNU. Notre Dame de Namur University. https://www.ndnu.edu/history-of-dei-the-evolution-of-diversity-training-programs/

Government of Canada. (2017). Many voices one mind: A pathway to reconciliation. https://www.canada.ca/en/government/publicservice/wellness-inclusion-diversity-public-service/diversity-inclusion-public-service/knowledge-circle/many-voices.html#toc7

Indigenous Canada. (n.d.). World View. University of Alberta. https://www.coursera.org/lecture/indigenous-canada/indigenous-worldviews-xQwnm

Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc. (2016). Indigenous worldview vs. western worldview. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/indigenous-worldviews-vs-western-worldviews

Kilawna, K. (2022). Meet the sqilxw women who are decolonizing the workplace. IndigiNews. https://indiginews.com/features/elaine-alec-shares-what-it-means-to-decolonize-the-workplace?gad_source=1&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI_8HK2e-BiQMVBDYIBR2UfDUEEAAYAyAAEgLUh_D_BwE

Kouri-Towe, N., & Martel-Perry, M. (2024). Better practices in the classroom. Concordia University. https://opentextbooks.concordia.ca/teachingresource/

Potter, R., & Hylton. T. (2019). Intercultural relations. Technical writing essentials. https://pressbooks.senecapolytechnic.ca/technicalwriting/wp-admin/post.php?post=2253&action=edit

Public Service Alliance of Canada. (2024). Shocking internal report exposes rampant discrimination at the head of Canada’s public service. https://psacunion.ca/shocking-internal-report-exposes-rampant

Ravishankar, R. A. (2023). A guide to becoming a better ally. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2023/06/a-guide-to-becoming-a-better-ally

Rose, M. (2021). Indigenous worldview: What is it, and how it is different [Video]? Youtube . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4KzqMMYatc4

Sanala. (n.d.). salana.com. https://www.sanalaplanning.com/

Skoden. (2022). Teaching, talking, and sharing about and for reconciliation. Seneca College. Skoden – Simple Book Publishing

Sue, D. W. (2021). Microaggressions and the “lived experience” of marginality. Division 45. https://division45.org/microaggressions-and-the-lived-experience-of-marginality/

Sue, D. W., Calle, C. Z., Mendez, N., Alsaidi, S., Glaeser, E. (2020). Microintervention strategies: What you can do to disarm and dismantle individual and systemic racism and bias. https://www.google.ca/books/edition/Microintervention_Strategies/GaIQEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover.

TedxTalks. (2024). Decolonizing the workplace [Video]. TedxFrisco. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lg7fMbN1MjI

Thurton, D. (2024). Internal report describes a ‘cesspool of racism’ in the federal public service. CBCNews. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/racism-federal-public-service-black-1.7378963

United Nations. (2023). Summary of the panel discussion on the negative impact of the legacies of colonialism on the enjoyment of human rights. General Assembly. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/sessions-regular/session54/A_HRC_54_4_accessible.pdf

Unit Nations (n.d.). Racism, discrimination are legacies of colonialism. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/get-involved/stories/racism-discrimination-are-legacies-colonialism#:~:text=Cal%C3%AD%20Tzay%20added%20that%20the,of%20language%20and%20culture%2C%20and

Wilson, K., & Hodgson, C. (2018). Colonization. Pulling Together: Foundations Guide. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfoundations/chapter/colonization/

Williams, J. (2020). Why corporate diversity programs fail and why small tweaks can have big impacts [Video]. TedxMileHigh. https://www.ted.com/talks/joan_c_williams_why_corporate_diversity_programs_fail_and_how_small_tweaks_can_have_big_impact

Williams, J. C., & Mihaylo, S. (2019). How the best bosses interrupt biases on their teams. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/11/how-the-best-bosses-interrupt-bias-on-their-teams

Workday. (2024). Workday DEI landscape report: Business leaders remain committed in 2024. Human Resources. https://blog.workday.com/en-us/workday-dei-landscape-report-business-leaders-remain-committed-2024.html#:~:text=While%20DEI%20faced%20challenges%20in,of%2011%25%20compared%20to%20last

In the era of AI hallucinations, “fake news,” deliberate misinformation, and “alternative facts,” businesses must rely on solid and verifiable information to move their efforts forward. Finding reliable information can be easy, if you know where to look and how to evaluate it. You may already be familiar with traditional sources of information, like library databases, government publications, journals, and the like, but with the increasing use of AI in data gathering, you may also want to consider non-traditional sources as well. This chapter will guide you on finding credible sources and evaluating research information using traditional and non-traditional resources.

Finding Research Information

Research can be obtained from primary and secondary sources. Primary research consists of original work, like experiments, focus groups, interviews, and the like, that generates raw information or data that are then interpreted in reporting. Secondary research consists of finding information and data that have been gathered by others and typically reported and published in some usable form. More often than not, researchers use both types of research in order to create a balance between original data and those already interpreted by other researchers.

Primary Research

Primary research is any research that you do yourself in which you collect raw data directly from the “real world” rather than from articles, books, or internet sources that have already collected and analyzed the data. Primary research in business is most often gathered through interviews, surveys and observations:

- Interviews: one-on-one or small group question and answer sessions. Interviews will provide detailed information from a small number of people and are useful when you want to get an expert opinion on your topic. For such interviews, you may need to have the participants sign an informed consent form before you begin.

- Surveys/Questionnaires: a form of questioning that is less flexible than interviews, as the questions are set ahead of time and cannot be changed. These involve much larger groups of people than interviews but result in fewer detailed responses. Informed consent is made a condition of survey completion: The purpose of the survey/questionnaire and how data will be treated are explained in the introductory. Participants then choose to proceed or not.

- Naturalistic observation in non-public venues: involves taking organized notes about occurrences related to your research. Observations allow you to gain objective information without the potentially biased viewpoint of an interview or survey. In naturalistic observations, the goal is to be as unobtrusive as possible, so that your presence does not influence or disturb the normal activities you want to observe. If you want to observe activities in a specific workplace, classroom, or other non-public places, you must first seek permission from the manager of that place and let participants know the nature of the observation. Observations in public places do not normally require approval. However, you may not photograph or video your observations without first getting the participants’ informed voluntary consent and permission.

While these are the most common methods, others are also gaining traction. Some examples of primary research include engaging with people and their information via social media, creating focus groups, engaging in beta-testing or prototype trials, medical and psychological studies, etc., some of which require a detailed review process.

Secondary Research

Secondary research information can be obtained from a variety of sources, some of which involve a slow publication process such as academic journals, while others involve a more rapid publication process, such as magazines (see Figure 7.3.1). Academic journals typically involve a slow publication process due to the peer review cycle. They contain articles written by scholars, often presenting their original research, reviewing the original research of others, or performing a “meta-analysis” (an analysis of multiple studies that analyze a given topic). The peer review process involves the evaluation and critique of pre-publication versions of articles, which give the authors the opportunity to justify and revise their work. Once this process is complete (it may take several review cycles and up to two years), the article is then published. This often rigorous peer review process is what helps to validate research reporting and why such articles are considered of greater reliability than unreviewed materials.

Figure 7.3.1 Examples of Popular vs Scholarly Sources (Last, 2019).1

Valid information can also be found in popular publications, however. Such publications have a more rapid publication process without peer review. Though the contents of articles published here are often of high quality, they are always the subject of extra scrutiny and skepticism when used in research because of the lack of peer oversight. In addition, such publications may have editorial boards that serve specific political, religious, economic, or social agendas, which may create a bias in the type of content offered. So be selective as to which popular publication you turn to for information.

For more information on popular vs scholarly articles, watch this Seneca Libraries video: Popular and Scholarly Resources.

Traditional academic sources: Scholarly articles published in academic journals are usually required sources in academic research; they are also an integral part of business reports. But they are not the only sources for credible information. Since you are researching in a professional field and preparing for the workplace, you will draw upon many kinds of traditional credible sources. Table 7.3.1 lists several types of such sources.

Table 7.3.1 Typical traditional academic research sources for business

| [Skip Table] |

|

| Traditional Academic Secondary Sources | Description |

|---|---|

| Academic Journals, Conference Papers, Dissertations, etc. |

Scholarly (peer-reviewed) academic sources publish primary research done by professional researchers and scholars in specialized fields, as well as reviews of that research by other specialists in the same field. For example, the Journal of Computer and System Sciences publishes original research papers in computer science and related subjects in system science; the International Journal of Business Communication is one of the most highly ranked journals in the field. |

| Reference Works—often considered tertiary sources |

Specialized encyclopedias, handbooks, and dictionaries can provide useful terminology and background information. For example, the Encyclopedia of Business and Finance is a widely recognized authoritative source. You may cite Wikipedia or dictionary.com in a business report, but be sure to compare the information to other reliable sources before use. |

| Books

Chapters in Books |

Books written by specialists in a given field usually contain reliable information and a References section that can be very helpful in providing a wealth of additional sources to investigate. For example, The Essential Guide to Business Communication for Finance Professionals by Jason L. Snyder and Lisa A.G. Frank. has an excellent chapter on presentation skills. |

| Trade Magazines and Popular Science Magazines |

Reputable trade magazines contain articles relating to current issues and innovations; therefore, they can be useful in determining what is “cutting edge," or finding out what current issues or controversies are affecting business. Examples include The Harvard Business Review, The Economist, and Forbes. |

| Newspapers (Journalism) |

Newspaper articles and media releases offer a sense of what journalists and people in industry think the general public should know about a given topic. Journalists report on current events and recent innovations; more in-depth “investigative journalism” explores a current issue in greater detail. Newspapers also contain editorial sections that provide personal opinions on these events and issues. Choose well-known, reputable newspapers such as The Globe and Mail. |

| Industry Websites (.com) |

Commercial websites are generally intended to “sell" a product or service, so you have to select information carefully. These websites can also give you insights into a company’s “mission statement,” organization, strategic plan, current or planned projects, archived information, white papers, business reports, product details, costs estimates, annual reports, etc. |

| Organization Websites (.org) |

A vast array of .org sites can be very helpful in supplying data and information. These are often public service sites and are designed to share information with the public. |

| Government Publications and Public Sector Websites (.gov/.edu/.ca) |

Government departments often publish reports and other documents that can be very helpful in determining public policy, regulations, and guidelines that should be followed. Statistics Canada, for example, publishes a wide range of data. University websites also offer a wide array of non-academic information, such as strategic plans, facilities information, etc. |

| Patents |

You may have to distinguish your innovative idea from previously patented ideas; you can look these up and get detailed information on patented or patent-pending ideas. |

| Public Presentations |

Public consultation meetings and representatives from business and government speak to various audiences about current issues and proposed projects. These can be live presentations or video presentations available on YouTube or TED talks. |

| Other |

Can you think of some more? (Radio programs, podcasts, social media, etc.) |

You may want to check out Seneca Libraries Business Library Guide for information on various academic sources for business research information.

Business-related sources: The use of AI and other technologies such as sensors and satellites in information collection has also led to other types of information sources that may not be considered the norm, but which nonetheless offer equally valuable and credible research information. Some of these are used to collect large amounts of data (big data). Here in Table 7.3.2 is a selection of such sources (Note: Copilot and Elicit are the only approved AI tools at Seneca):

Table 7.3.2 Business-related secondary sources (CIRI, 2018; Microsoft, 2025)*

*NOTE: These non-traditional research sources are used in business and industry, but would not normally be used for academic research.

| Business-Related Secondary Sources | Description |

| Automated Searches | AI tools like Elicit and Consensus will use key words and research questions to quickly aggregate relevant academic publications available in the Semantic Scholar database. Such tools offer additional features, such as summarization, insights, and citations. ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude, and other LLM models are also being used for searches. Though their accuracy and citations are improving and vary from model to model, output must be carefully reviewed prior to use. |

| Social Media

LinkedIn, X, Blue Sky, Mastodon, Facebook Groups |

Depending on who you follow, you can find brief useable content and links to articles and other information that can be used as research sources on social media. For example, experts on LinkedIn, Blue Sky, and X often share their published research, blog posts, videos, and other materials that are then discussed by other experts. The original posts, attachments/links, and comments are all rich sources of information, but they must be carefully evaluated prior to use. |

| Alternative Media | News sources such as found in Canadian sites like Rabble and magazines like The Walrus offer timely articles on current events, politics, and social issues. A variety of alternative news sources exist that satisfy a range of political and social perspectives, both from the left and the right, so you must use a critical lens to evaluate these sources for bias. |

| Alternative Financial and Other Worlds | Cryptocurrency and metaverse (simulated worlds and gaming) data are growing sources of information for consumer behaviour, investment, game development, and financial trends. |

| Blogs | Experts in various fields post theories, research findings, and developing thinking on the latest topics in their field on blogs like Wordpress or Substack or on personal websites. Be selective as blog postings usually consist of work in progress, so the thinking can change depending on what the author's research reveals over time. |

| Online Communities | Sites like Reddit and Discord are digital communities where posts are organized according to interest areas. Carefully evaluate all information for credibility and accuracy as the posts are often opinion and experience based. |

| Crowdsourcing Platforms | Research into new products, services, and tools that are in the pre-release phases can be done by searching not only patents but also crowdsourcing platforms like Kickstarter and StackExchange. |

| Sensor and Wearable Technologies | Sensor and wearable technology data such as heart monitors, fitness sensors, diabetes monitors, car health, smart meters, and the lise all aid in the collection of personal, physical, mechanical, and environmental data and the like. |

| Mobile and Transactional Applications | Mobile apps will collect data on user behaviour, consumer preferences, and other information. Transactional technologies will capture data relating to financial, retail, consumer behaviour and preferences, and the like |

| Website and Other Internet Technologies | The internet can collect data about consumer behaviours and operations from various devices as they link to the network. Specific websites collect data on usage, page views, and consumer behaviours. Some tools will scrape the internet to collect data on competitors, market price trends, and product availability. |

| Satellite and Geolocation Technologies | Satellite data and imagery, such as gathered by Orbital Insight, can assist with geospatial information gathering that can be used areas like supply chain, real estate, as well as governance and geopolitics. Geolocation data is collected from devices that permit the gathering of information based on geographical location. SafeGraph and Placer.ai, for example, gather data and create insights relating to location, foot traffic, community context, and more to develop marketing and branding information. |

| Weather and Environmental Technologies | In the real estate, manufacturing, supply chain, aviation, and agricultural sectors, for example, instruments gather data that will provide information on weather patterns and trends, air and water quality, soil and air conditions, water levels and conditions, as well as other factors. |

Be reminded that when gathering, storing, and using data, especially that related to people's personal information, you must abide by the Canadian federal and provincial privacy laws. Please refer to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) and Ontario’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) for more information. See more about protecting people's information in Chapter 7.5 Research Ethics.

Deep Research Reasoners and Agents

LLMs have developed autonomous reasoning capabilities to the point that the technologies can now complete complex research, and paired with agentic technologies, they can do so autonomously (McFarland, 2025; Mollick, 2025). Open AI's Deep Research and Google's Deep Research, for example, are AI agents (autonomous, task-focused AI tools) that are able to produce copious and largely reliable analyses, summaries, insights, and other materials based on materials and direction provided by researchers.

The Google and OpenAI tools are not the same, however. As Alex McFarland (2025), AI Journalist, points out, the capabilities of each model differ substantially. For example, OpenAI's Deep Research will go about the research in a less structured manner than Google's model resulting in broader and more comprehensive research results that are reliable and of high quality (Mollick, 2025). The output reveals that the agent in OpenAI's case, will take a more creative approach that follows information as it is revealed and takes unexpected avenues of search to reveal deep information. In addition OpenAI's model will show its reasoning process (McFarland, 2025; Mollick, 2025). On the other hand, Google's Deep Research uses a more structured approach that relies heavily on information provided by the user (McFarland, 2025). The output will be limited to primary information, reports, and links that are often culled from websites including paywalled sites that vary in quality and reliability (Mollick, 2025).

The kind of research you are doing will help determine what you want to pay for access. According to McFarland (2025), if you are a professional in finance, academia, or policy, for example, it would be worth it to use OpenAI's model; on the other hand, if you are a casual user, then the Google model would be better suited for you. Be reminded that Copilot is the only approved LLM for use at Seneca and really should not be used for research purposes.

Evaluating Research Materials

Mark Twain, supposedly quoting British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, famously said, "There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics." On the other hand, H.G. Wells has been (mis)quoted as stating, "statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write" (Quora, n.d.). The fact that the actual sources for both “quotations” are unverifiable makes their sentiments no less true. The effective use of statistics can play a critical role in influencing public opinion as well as persuading in the workplace. However, as the fame of the first quotation indicates, statistics can be used to mislead rather than accurately inform—whether intentionally or unintentionally.

The importance of critically evaluating your sources for authority, relevance, timeliness, and credibility can therefore not be overstated. Anyone can put anything on the internet; and people with strong web and document design skills can make this information look very professional and credible—even if it isn't. Moreover, LLMs are notorious for producing content that is in accurate and often unverifiable. Since much research is currently done online, and many sources are available electronically, developing your critical evaluation skills is crucial to finding valid, credible evidence to support and develop your ideas. In fact, corroboration of information has become such a challenging issue that there are sites like this List of Predatory Journals that regularly update its online list of journals that subvert the peer review process and simply publish for profit.

When evaluating research sources, regardless of their origin (LLM or traditional research) be careful to critically evaluate the authority, content, and purpose of the material, using questions in Table 7.3.3. You should also ensure that the claims included in LLM output include source information and that you corroborate or check those sources for accuracy. For more information on evaluating sources, also view this brief Seneca Libraries video, Evaluating Websites.

And it may be tempting to use an LLM to go through the output it created to check for accuracy and bias. But why would you do that? If it created erroneous or unsupported content to begin with, you would not want it to check its own output. That's your responsibility. Here are some tools to help you through this process.

Table 7.3.3 A question-guide for evaluations of the authority, content, and purpose of information

| [Skip Table] |

|

| Authority Researchers Authors Creators |

Who are the researchers/authors/creators? Who is their intended audience? What are their credentials/qualifications? What else has this author written? Is this research funded? By whom? Who benefits? Who has intellectual ownership of this idea? How do I cite it? Where is this source published? What kind of publication is it? Authoritative Sources: written by experts for a specialized audience, published in peer-reviewed journals or by respected publishers, and containing well-supported, evidence-based arguments. Popular Sources: written for a general (or possibly niche) public audience, often in an informal or journalistic style, published in newspapers, magazines, and websites with a purpose of entertaining or promoting a product; evidence is often “soft” rather than hard. |

|---|---|

|

Content |

Methodology What is the methodology of the study? Or how has evidence been collected? Is the methodology sound? Can you find obvious flaws? What is its scope? Does it apply to your project? How? How recent and relevant is it? What is the publication date or last update? |

|

Data Is there sufficient data to support their claims or hypotheses? Do they offer quantitative and/or qualitative data? Are visual representations of the data misleading or distorted in some way? |

|

|

Purpose |

Why has this author presented this information to this audience? Why am I using this source? Will using this source bolster my credibility or undermine it? Am I “cherry-picking” – using inadequate or unrepresentative data that only supports my position, while ignoring substantial amount of data that contradicts it? Could “cognitive bias” be at work here? Have I only consulted the kinds of sources I know will support my idea? Have I failed to consider alternative kinds of sources? Am I representing the data I have collected accurately? Are the data statistically relevant or significant? |

Knowledge Check

Beware of Logical Fallacies

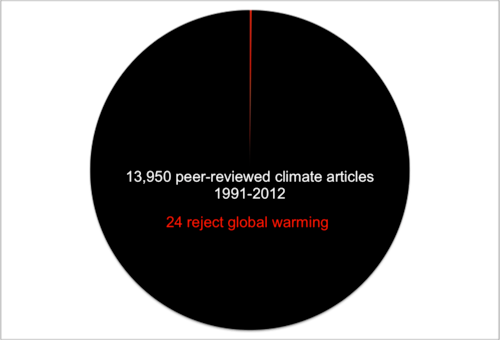

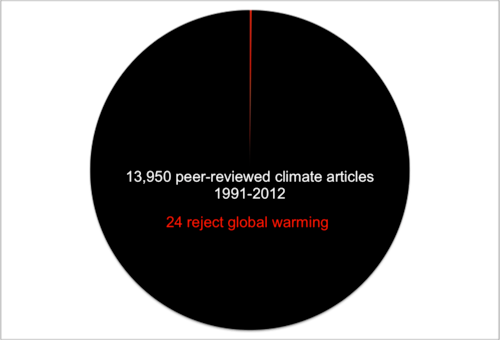

We all have biases when we write or argue; however, when evaluating sources, you want to be on the lookout for bias that is unfair, one-sided, or slanted. Here is an example: Given the pie chart in Figure 7.3.2, if you only consulted articles that rejected global warming in a project related to that topic, you would be guilty of cherry-picking and cognitive bias.

When evaluating a source, consider whether the author has acknowledged and addressed opposing ideas, potential gaps in the research, or limits of the data. Look at the kind of language the author uses: Is it slanted, strongly connotative, or emotionally manipulative? Is the supporting evidence presented logically, credibly, and ethically? Has the author cherry-picked or misrepresented sources or ideas? Does the author rely heavily on emotional appeal? There are many logical fallacies that both writers and readers can fall prey to (see Table 7.3.4 and for more information refer to Chapter 3.4 ). It is important to use data ethically and accurately, and to apply logic correctly and validly to support your ideas.

Table 7.3.4 Common logical fallacies

| [Skip Table] | |

| Bandwagon Fallacy |

Argument from popularity – “Everyone else is doing it, so we should too!” |

|---|---|

| Hasty Generalization |

Using insufficient data to come to a general conclusion. E.g., An Australian stole my wallet; therefore, all Australians are thieves! |

| Unrepresentative Sample |

Using data from a particular subset and generalizing to a larger set that may not share similar characteristics. E.g., Giving a survey to only female students under 20 and generalizing results to all students. |

| False Dilemma |

“Either/or fallacy” – presenting only two options when there are usually more possibilities to consider E.g., You're either with us or against us. |

| Slippery Slope |

Claiming that a single cause will lead, eventually, to exaggerated catastrophic results. |

| Slanted Language |

Using language loaded with emotional appeal and either positive or negative connotation to manipulate the reader |

| False Analogy |

Comparing your idea to another that is familiar to the audience but which may not have sufficient similarity to make an accurate comparison E.g., Governing a country is like running a business. |

| Post hoc, ergo prompter hoc |

“After this; therefore, because of this” E.g., A happened, then B happened; therefore, A caused B. Just because one thing happened first, does not necessarily mean that the first thing caused the second thing. |

| Circular Reasoning |

Circular argument - assuming the truth of the conclusion by its premises. E.g., I never lie; therefore, I must be telling the truth. |

| Ad hominem |

An attack on the person making an argument does not really invalidate that person’s argument. It might make them seem a bit less credible, but it does not dismantle the actual argument or invalidate the data. |

| Straw Man Argument |

Restating the opposing idea in an inaccurately absurd or simplistic manner to more easily refute or undermine it. |

| Others? |

There are many more… can you think of some? For a bit of fun, check out Spurious Correlations. |

Please refer to Chapter 3.4 Writing to Persuade to find out how you can check your work for logical fallacies.

Knowledge Check

Critical thinking lies at the heart of evaluating sources. You want to be rigorous in your selection of evidence because, once you use it in your paper, it will either bolster your own credibility or undermine it.

Notes

- Cover images from journals are used to illustrate the difference between popular and scholarly journals, and are for noncommercial, educational use only.

References

Canadian Investor Relations Institute (CIRI).(2018) CIRI advisor - Using Non-Traditional Data for Market and Competitive Int....pdf

Government of Canada. Statistics Canada. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/start

Last, S. (2019). Technical writing essentials. BCcampus. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/

Microsoft. (2025, January 20). Non-traditional sources of information. Copilot 4o, Microsoft Enterprise Version.

McFarland, A. (2025, updated February 5). Google Gemini vs. OpenAI Deep Research: Which Is Better? - Techopedia

Mollick, E. (2025, February 3). The End of Search, The Beginning of Research

Seneca Libraries. (2013, July 2). Evaluating Websites [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/35PBCC5TKxs

Seneca Libraries. (2013, July 2). Popular and Scholarly Resources [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/wPj-BBB0le4

Seneca Libraries. (2021, January 4 updated). Writing and Communicating Technical Information: Key Resources. Seneca College. https://library.senecacollege.ca/technical/keyresources

What is the source of the H.G. Wells quote, ‘Statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write/”? (n.d.). Quora. https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-source-of-the-H-G-Wells-quote-Statistical-thinking-will-one-day-be-as-necessary-for-efficient-citizenship-as-the-ability-to-read-and-write

Wright-Tau, C. (2013). There’s No Denying It: Global Warming is Happening | Home on the Range

In the era of AI hallucinations, “fake news,” deliberate misinformation, and “alternative facts,” businesses must rely on solid and verifiable information to move their efforts forward. Finding reliable information can be easy, if you know where to look and how to evaluate it. You may already be familiar with traditional sources of information, like library databases, government publications, journals, and the like, but with the increasing use of AI in data gathering, you may also want to consider non-traditional sources as well. This chapter will guide you on finding credible sources and evaluating research information using traditional and non-traditional resources.

Finding Research Information

Research can be obtained from primary and secondary sources. Primary research consists of original work, like experiments, focus groups, interviews, and the like, that generates raw information or data that are then interpreted in reporting. Secondary research consists of finding information and data that have been gathered by others and typically reported and published in some usable form. More often than not, researchers use both types of research in order to create a balance between original data and those already interpreted by other researchers.

Primary Research

Primary research is any research that you do yourself in which you collect raw data directly from the “real world” rather than from articles, books, or internet sources that have already collected and analyzed the data. Primary research in business is most often gathered through interviews, surveys and observations:

- Interviews: one-on-one or small group question and answer sessions. Interviews will provide detailed information from a small number of people and are useful when you want to get an expert opinion on your topic. For such interviews, you may need to have the participants sign an informed consent form before you begin.

- Surveys/Questionnaires: a form of questioning that is less flexible than interviews, as the questions are set ahead of time and cannot be changed. These involve much larger groups of people than interviews but result in fewer detailed responses. Informed consent is made a condition of survey completion: The purpose of the survey/questionnaire and how data will be treated are explained in the introductory. Participants then choose to proceed or not.

- Naturalistic observation in non-public venues: involves taking organized notes about occurrences related to your research. Observations allow you to gain objective information without the potentially biased viewpoint of an interview or survey. In naturalistic observations, the goal is to be as unobtrusive as possible, so that your presence does not influence or disturb the normal activities you want to observe. If you want to observe activities in a specific workplace, classroom, or other non-public places, you must first seek permission from the manager of that place and let participants know the nature of the observation. Observations in public places do not normally require approval. However, you may not photograph or video your observations without first getting the participants’ informed voluntary consent and permission.

While these are the most common methods, others are also gaining traction. Some examples of primary research include engaging with people and their information via social media, creating focus groups, engaging in beta-testing or prototype trials, medical and psychological studies, etc., some of which require a detailed review process.

Secondary Research

Secondary research information can be obtained from a variety of sources, some of which involve a slow publication process such as academic journals, while others involve a more rapid publication process, such as magazines (see Figure 7.3.1). Academic journals typically involve a slow publication process due to the peer review cycle. They contain articles written by scholars, often presenting their original research, reviewing the original research of others, or performing a “meta-analysis” (an analysis of multiple studies that analyze a given topic). The peer review process involves the evaluation and critique of pre-publication versions of articles, which give the authors the opportunity to justify and revise their work. Once this process is complete (it may take several review cycles and up to two years), the article is then published. This often rigorous peer review process is what helps to validate research reporting and why such articles are considered of greater reliability than unreviewed materials.

Figure 7.3.1 Examples of Popular vs Scholarly Sources (Last, 2019).1

Valid information can also be found in popular publications, however. Such publications have a more rapid publication process without peer review. Though the contents of articles published here are often of high quality, they are always the subject of extra scrutiny and skepticism when used in research because of the lack of peer oversight. In addition, such publications may have editorial boards that serve specific political, religious, economic, or social agendas, which may create a bias in the type of content offered. So be selective as to which popular publication you turn to for information.

For more information on popular vs scholarly articles, watch this Seneca Libraries video: Popular and Scholarly Resources.

Traditional academic sources: Scholarly articles published in academic journals are usually required sources in academic research; they are also an integral part of business reports. But they are not the only sources for credible information. Since you are researching in a professional field and preparing for the workplace, you will draw upon many kinds of traditional credible sources. Table 7.3.1 lists several types of such sources.

Table 7.3.1 Typical traditional academic research sources for business

| [Skip Table] |

|

| Traditional Academic Secondary Sources | Description |

|---|---|

| Academic Journals, Conference Papers, Dissertations, etc. |

Scholarly (peer-reviewed) academic sources publish primary research done by professional researchers and scholars in specialized fields, as well as reviews of that research by other specialists in the same field. For example, the Journal of Computer and System Sciences publishes original research papers in computer science and related subjects in system science; the International Journal of Business Communication is one of the most highly ranked journals in the field. |

| Reference Works—often considered tertiary sources |

Specialized encyclopedias, handbooks, and dictionaries can provide useful terminology and background information. For example, the Encyclopedia of Business and Finance is a widely recognized authoritative source. You may cite Wikipedia or dictionary.com in a business report, but be sure to compare the information to other reliable sources before use. |

| Books

Chapters in Books |

Books written by specialists in a given field usually contain reliable information and a References section that can be very helpful in providing a wealth of additional sources to investigate. For example, The Essential Guide to Business Communication for Finance Professionals by Jason L. Snyder and Lisa A.G. Frank. has an excellent chapter on presentation skills. |

| Trade Magazines and Popular Science Magazines |

Reputable trade magazines contain articles relating to current issues and innovations; therefore, they can be useful in determining what is “cutting edge," or finding out what current issues or controversies are affecting business. Examples include The Harvard Business Review, The Economist, and Forbes. |

| Newspapers (Journalism) |

Newspaper articles and media releases offer a sense of what journalists and people in industry think the general public should know about a given topic. Journalists report on current events and recent innovations; more in-depth “investigative journalism” explores a current issue in greater detail. Newspapers also contain editorial sections that provide personal opinions on these events and issues. Choose well-known, reputable newspapers such as The Globe and Mail. |

| Industry Websites (.com) |

Commercial websites are generally intended to “sell" a product or service, so you have to select information carefully. These websites can also give you insights into a company’s “mission statement,” organization, strategic plan, current or planned projects, archived information, white papers, business reports, product details, costs estimates, annual reports, etc. |

| Organization Websites (.org) |

A vast array of .org sites can be very helpful in supplying data and information. These are often public service sites and are designed to share information with the public. |

| Government Publications and Public Sector Websites (.gov/.edu/.ca) |

Government departments often publish reports and other documents that can be very helpful in determining public policy, regulations, and guidelines that should be followed. Statistics Canada, for example, publishes a wide range of data. University websites also offer a wide array of non-academic information, such as strategic plans, facilities information, etc. |

| Patents |

You may have to distinguish your innovative idea from previously patented ideas; you can look these up and get detailed information on patented or patent-pending ideas. |

| Public Presentations |

Public consultation meetings and representatives from business and government speak to various audiences about current issues and proposed projects. These can be live presentations or video presentations available on YouTube or TED talks. |

| Other |

Can you think of some more? (Radio programs, podcasts, social media, etc.) |

You may want to check out Seneca Libraries Business Library Guide for information on various academic sources for business research information.

Business-related sources: The use of AI and other technologies such as sensors and satellites in information collection has also led to other types of information sources that may not be considered the norm, but which nonetheless offer equally valuable and credible research information. Some of these are used to collect large amounts of data (big data). Here in Table 7.3.2 is a selection of such sources (Note: Copilot and Elicit are the only approved AI tools at Seneca):

Table 7.3.2 Business-related secondary sources (CIRI, 2018; Microsoft, 2025)*

*NOTE: These non-traditional research sources are used in business and industry, but would not normally be used for academic research.

| Business-Related Secondary Sources | Description |

| Automated Searches | AI tools like Elicit and Consensus will use key words and research questions to quickly aggregate relevant academic publications available in the Semantic Scholar database. Such tools offer additional features, such as summarization, insights, and citations. ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude, and other LLM models are also being used for searches. Though their accuracy and citations are improving and vary from model to model, output must be carefully reviewed prior to use. |

| Social Media

LinkedIn, X, Blue Sky, Mastodon, Facebook Groups |

Depending on who you follow, you can find brief useable content and links to articles and other information that can be used as research sources on social media. For example, experts on LinkedIn, Blue Sky, and X often share their published research, blog posts, videos, and other materials that are then discussed by other experts. The original posts, attachments/links, and comments are all rich sources of information, but they must be carefully evaluated prior to use. |

| Alternative Media | News sources such as found in Canadian sites like Rabble and magazines like The Walrus offer timely articles on current events, politics, and social issues. A variety of alternative news sources exist that satisfy a range of political and social perspectives, both from the left and the right, so you must use a critical lens to evaluate these sources for bias. |

| Alternative Financial and Other Worlds | Cryptocurrency and metaverse (simulated worlds and gaming) data are growing sources of information for consumer behaviour, investment, game development, and financial trends. |

| Blogs | Experts in various fields post theories, research findings, and developing thinking on the latest topics in their field on blogs like Wordpress or Substack or on personal websites. Be selective as blog postings usually consist of work in progress, so the thinking can change depending on what the author's research reveals over time. |

| Online Communities | Sites like Reddit and Discord are digital communities where posts are organized according to interest areas. Carefully evaluate all information for credibility and accuracy as the posts are often opinion and experience based. |

| Crowdsourcing Platforms | Research into new products, services, and tools that are in the pre-release phases can be done by searching not only patents but also crowdsourcing platforms like Kickstarter and StackExchange. |

| Sensor and Wearable Technologies | Sensor and wearable technology data such as heart monitors, fitness sensors, diabetes monitors, car health, smart meters, and the like all aid in the collection of personal, physical, mechanical, and environmental data. |

| Mobile and Transactional Applications | Mobile apps will collect data on user behaviour, consumer preferences, and other information. Transactional technologies will capture data relating to financial, retail, consumer behaviour and preferences, and the like |

| Website and Other Internet Technologies | The internet can collect data about consumer behaviours and operations from various devices as they link to the network. Specific websites collect data on usage, page views, and consumer behaviours. Some tools will scrape the internet to collect data on competitors, market price trends, and product availability. |

| Satellite and Geolocation Technologies | Satellite data and imagery, such as gathered by Orbital Insight, can assist with geospatial information gathering that can be used areas like supply chain, real estate, as well as governance and geopolitics. Geolocation data is collected from devices that permit the gathering of information based on geographical location. SafeGraph and Placer.ai, for example, gather data and create insights relating to location, foot traffic, community context, and more to develop marketing and branding information. |