A1: Indigenous Peoples: A Brief History

For many of us, information contained in history books is considered an accurate reflection of our past. But what happens when that information is not factual or true? What happens when history reflects the perspective of “those who held the most power [and] chose the stories that were to become a part of history” (Johnson, n.d., para 2). What happens when history is used as a tool of the powerful to justify and retain power? Canadian history, as told by history books, has “discounted, ignored, and erased from history” (Johnson, n.d., para 2) the existence and contributions of Indigenous peoples. This chapter looks to the seldom acknowledged vibrant life being lived on Turtle Island long before colonization by Europeans. If we are to understand the present, it is important to have more than the colonizers’ version of history.

Pre-Colonial Contact

Typically, for decades, the Canadian history shared and taught began with colonization — with explorers and adventurers discovering a vast land that was sparsely populated by savages. Thankfully, that narrative is beginning to change. What can be said though with certainty about what life was like on Turtle Island before colonization?

Given the vastness and climate diversity of the land now known as Canada, it is important to consider how the way of life would have differed for people living in different regions of this land. One of the things that would have been common though is a connection to water not just for survival, but as a significant cultural signifier. The traditions and ways of life of the many nations across Turtle Island were influenced by the water features near them.

A lot of what is known about the way of life on Turtle Island pre-contact comes from the archeological evidence, but also from the journals and reports of the early colonists. We know that plants were being used for medicinal purposes, maple sugaring was common, and corn, beans, squash, rice, and other vegetables were being harvested.

Pan-Indigenizing, making overarching statements that apply to all Indigenous people, is problematic. This is especially the case when it comes to governance and leadership. From the stories and traditions that have been passed down, some communities were hierarchical, either with patriarchal or matriarchal leadership, while others relied solely on the circle governance model of all voices being heard in decision-making. It is also known that Two-Spirit people were highly revered and looked to for guidance as they hold the gifts of both genders and can see things from more than one gender viewpoint.

One final element of life to mention here is that of cooperation and sharing. Many alliances, confederacies, and treaties between nations were held long before colonization. These were always undertaken in the spirit of cooperation, the sharing of resources, trade, and peace.

For a detailed look at what is known about the way of life pre-contact, see: The Standard of Living Before European Settlement.

PBS aired a four-episode series called Native America that examines the way of life in the Americas before colonization. While heavily focused on the United States and South America, much can be learned about the history of the land we are presently on through this series. You can access the series through clips provided on the Native America in the Classroom website.

Colonial History and Legacy

It is important to understand that the history of colonization begins with rather peaceful and mutually beneficial interactions between Europeans and First Nations and Inuit populations. During first contact, Europeans relied on Indigenous people for successful trade and even survival. Early on there was an agreement between Indigenous people and Europeans to share the land. Both parties could see the mutual benefits of their trade relationship. This posture of friendship by Europeans was a facade used to win over trust in order to establish invasive strategies to displace Indigenous people.

A key strategy in the domination of Turtle Island is the Doctrine of Discovery; a doctrine of superiority that legitimized the colonization of sovereign Indigenous nations globally in the name of Christianity. This global take-over included the land of Indigenous people in what is now Canada.

The Doctrine of Discovery claimed that if land was vacant, it could be claimed by explorers in the name of the Monarchy. Since Indigenous people were non-Christian this meant they were less than human (savages), and therefore since the land was uninhabited by humans, Christian Europeans had the right to colonize whatever land they discovered.

The notion of terra nullius, meaning empty land, was also used to legitimize colonization. If the land was empty of humans, it was free for the taking. Since Indigenous people were non-Christian, they were uncivilized, nonhuman, or savage, and therefore the land was terra nullius and taking it was justified.

The Royal Proclamation

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 is a document that outlined European settlement of Indigenous land. King George III issued this document to provide guidelines of how Britain could claim territory. While much of the language in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 can be difficult to understand, the essence of the Proclamation is that Indigenous rights and territory are recognized by the Crown (at the time the British King but now the federal government). The Proclamation acknowledges that Indigenous title to land will continue to exist and that it would continue to exist as such unless ceded by a treaty. At the time, it was only the Crown that could purchase land and anyone that wished to buy land had to buy it from the Crown.

Although the Proclamation promises protection of Indigenous lands (when the proclamation states: their land shall never be molested or disturbed), this is still a colonial document that establishes a colonial view of land as possession. Also, it is a document that was created without the consultation of Indigenous peoples.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 is still a legitimate official document. Despite this, the settlement of Europeans began to grow in numbers, mostly without consultation or negotiation with Indigenous peoples of the territory. Sometimes, however, treaties were established between Indigenous peoples and the government to ensure Indigenous people were compensated for the land taken, although the fairness of these treaties are contested.

The following video provides an overview of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and its impact.

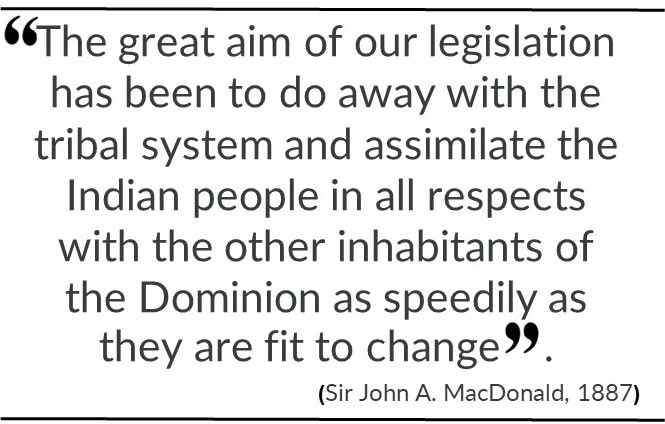

The Indian Act

Although Indigenous people had laws that were established long before colonization, the federal government wanted a more structured relationship of control over them, their communities, lands, and resources. The Indian Act was created with the purpose of assimilating First Nations people into European-Canadian society. The Indian Act has been historically discriminatory and oppressive, which has contributed to several violations of human rights. Many amendments have been made to the Act over the years but it is still a current piece of legislation used to outline various rules and regulations involving reserve land, governmental responsibilities of band councils, and other aspects of life for Indians with status. It is the Indian Act that defines who can and cannot acquire status.

Although Indigenous people had laws that were established long before colonization, the federal government wanted a more structured relationship of control over them, their communities, lands, and resources. The Indian Act was created with the purpose of assimilating First Nations people into European-Canadian society. The Indian Act has been historically discriminatory and oppressive, which has contributed to several violations of human rights. Many amendments have been made to the Act over the years but it is still a current piece of legislation used to outline various rules and regulations involving reserve land, governmental responsibilities of band councils, and other aspects of life for Indians with status. It is the Indian Act that defines who can and cannot acquire status.

For more information on the Indian Act, visit the webpage 21 Things You May Not Have Known About the Indian Act and read the list.

Treaties

Intent

The traditions and protocols of Indigenous treaties existed long before first contact with Europeans. Indigenous people had engaged in their own forms of governance for hundreds of years; sharing resources and building alliances between nations. For First Nations people, treaties are considered sacred. To honour their sacredness, protocols and negotiations involved ceremonial aspects such as a pipe ceremony or an exchange of symbolic items.

The peaceful and harmonious alliances between Indigenous groups that were formed hundreds of years ago still exist today. One of the most well-known examples of this is the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (also known as Six Nations or Iroquois Confederacy) and is considered the first democracy. The Haudenosaunee includes Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, and later included Tuscarora. There is also the Three Fires Confederacy beginning in the 1600s that is made up of Ojibway, Potawatomi, and Odawa nations. The Wabanaki Confederacy dates as far back as the 1680s and includes the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqey, Peskotomuhkatiyik, Abenaki, and Penobscot.

The Dish with One Spoon treaty between the Anishinaabe, Mississaugas, and Haudenosaunee nations living around the Great Lakes is an example of the spirit and intent in which First Nations would have entered into treaty agreements with Europeans. The sharing of resources for the sustenance of all in a spirit of peace and friendship was at the foundation of the treaty process from a First Nations perspective.

During early contact with Europeans, First Nations began negotiating peaceful co-existence with the newcomers. A well-known example of this is the Two-Row Wampum between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch that would ensure friendship, peace, and respect for as long as the sun shines, the grass grows, and the rivers flow. Indigenous groups across Turtle Island were familiar with the process of negotiation and treaty-making by the time of European contact; however, they were not prepared for the different approaches to the treaty process that Europeans would bring.

The Treaty Relationship

Treaties are not a thing of the past; they are living agreements with current obligations. We are all treaty people, and it is our responsibility to become educated on what it means to be a treaty partner.

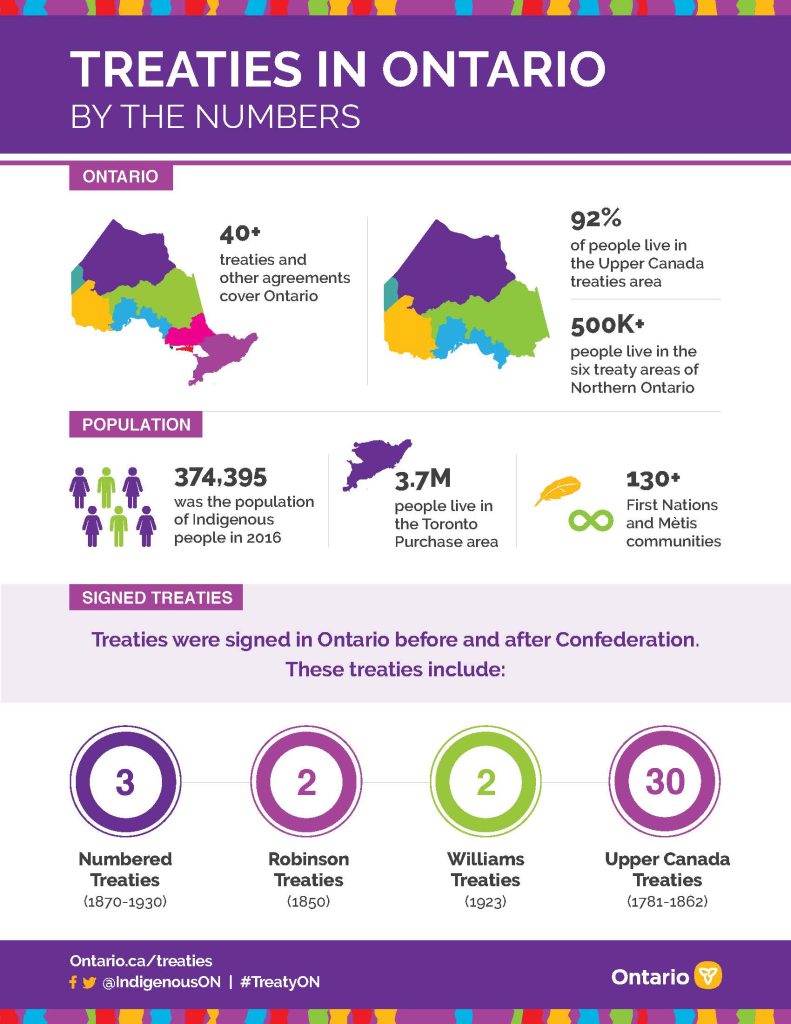

Treaties are legally binding agreements that set out the rights, responsibilities and relationships of First Nations and the federal and provincial governments. Ontario, where Seneca Polytechnic is located, and other areas in Canada, would not exist as it is today without treaties. They form the basis of the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Although many treaties were signed more than a century ago, treaty commitments are just as valid today as they were then (Ontario.ca, n.d.). A map of the many treaties that make-up Ontario is below. As you review the map, consider what Ontario would look like today if indigenous peoples were not removed from their land.

To gain more knowledge of what it means to be a treaty person, see We are all Treaty People below, a video that promotes Treaty Education within the Mi’kma’ki Territory (Nova Scotia).

The Government of Canada under the current Trudeau Liberal government has established ten principles respecting the Government of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples. As you read through these principles, consider how well the Government (Crown) is doing in living up to these principles, and what could you be doing to hold the government accountable to upholding these principles?

According to the GOC (2021) “these Principles are a starting point to support efforts to end the denial of Indigenous rights that led to disempowerment and assimilationist policies and practices. They seek to turn the page in an often troubled relationship by advancing fundamental change whereby Indigenous peoples increasingly live in strong and healthy communities with thriving cultures. To achieve this change, it is recognized that Indigenous nations are self-determining, self-governing, increasingly self-sufficient, and rightfully aspire to no longer be marginalized, regulated, and administered under the Indian Act and similar instruments” (para. 6).

When looking at treaties, it’s important to consider the different worldviews of Indigenous Peoples and European settlers. For Indigenous Nations, treaties were viewed as an equal relationship where both nations can live together and share the land. On the other hand, European settler governments didn’t view Indigenous Peoples as equals. They viewed treaties as a way to assimilate and remove Indigenous Peoples from their lands (Historica Canada).

Conclusion

The nation of Canada was founded on patriarchal, monarchist, Christian, white European colonialism. This chapter has presented some of this history and its ongoing impact on people who are First Nations, Métis, and Inuit. While some progress and change is happening, a very long road to reconciliation lies ahead for Canada and Indigenous peoples. In our next chapter, we’ll examine Canada’s path towards reconciliation.

Attributions

This page has been edited and remixed from the following sources. Supplemental information has been provided by Tricia Hylton.

College Libraries Ontario. (n.d.). Maamwi. The Learning Portal. https://tlp-lpa.ca/maamwi

“Skoden” Copyright © 2022 by Seneca College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

CBC News. (2018). How to talk about Indigenous people [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XEzjA5RoLv0

Chippewas of Rana First Nation. (2016). Justice Murray Sinclair on the Royal Proclamation of 1763 [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSQsyZDGoX0&t=2s.

Government of Canada. (n.d.). Principles of respecting the Government’s of Canada relationship with Indigenous Peoples. Canada’s System of Justice. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/principles-principes.html.

HistoricaCanada.ca. (n.d.) Treaties in Canada: Education guide. http://education.historicacanada.ca/files/104/Treaties_Printable_Pages.pdf

Johnson, S. (n.d.) Historical primer. Native land digital. https://native-land.ca/resources/teachers-guide/

Ontario.ca. (n.d.). Treaties in Ontario: By the Numbers [Infographic]. First Nations, Inuit and Metis. iao-treaties-in-toronto-infographic-en-2021-03-10.pdf (ontario.ca).

TheFPSChannel. (2021). Treaty education [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RElug0TiAZw

TVO Today. (2019). The Indian Act Explained [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OhBrq7Ez-rQ