7.3 Finding and Evaluating Research Information

In the era of AI hallucinations, “fake news,” deliberate misinformation, and “alternative facts,” businesses must rely on solid and verifiable information to move their efforts forward. Finding reliable information can be easy, if you know where to look and how to evaluate it. You may already be familiar with traditional sources of information, like library databases, government publications, journals, and the like, but with the increasing use of AI in data gathering, you may also want to consider non-traditional sources as well. This chapter will guide you on finding credible sources and evaluating research information using traditional and non-traditional resources.

Finding Research Information

Research can be obtained from primary and secondary sources. Primary research consists of original work, like experiments, focus groups, interviews, and the like, that generates raw information or data that are then interpreted in reporting. Secondary research consists of finding information and data that have been gathered by others and typically reported and published in some usable form. More often than not, researchers use both types of research in order to create a balance between original data and those already interpreted by other researchers.

Primary Research

Primary research is any research that you do yourself in which you collect raw data directly from the “real world” rather than from articles, books, or internet sources that have already collected and analyzed the data. Primary research in business is most often gathered through interviews, surveys and observations:

- Interviews: one-on-one or small group question and answer sessions. Interviews will provide detailed information from a small number of people and are useful when you want to get an expert opinion on your topic. For such interviews, you may need to have the participants sign an informed consent form before you begin.

- Surveys/Questionnaires: a form of questioning that is less flexible than interviews, as the questions are set ahead of time and cannot be changed. These involve much larger groups of people than interviews but result in fewer detailed responses. Informed consent is made a condition of survey completion: The purpose of the survey/questionnaire and how data will be treated are explained in the introductory. Participants then choose to proceed or not.

- Naturalistic observation in non-public venues: involves taking organized notes about occurrences related to your research. Observations allow you to gain objective information without the potentially biased viewpoint of an interview or survey. In naturalistic observations, the goal is to be as unobtrusive as possible, so that your presence does not influence or disturb the normal activities you want to observe. If you want to observe activities in a specific workplace, classroom, or other non-public places, you must first seek permission from the manager of that place and let participants know the nature of the observation. Observations in public places do not normally require approval. However, you may not photograph or video your observations without first getting the participants’ informed voluntary consent and permission.

While these are the most common methods, others are also gaining traction. Some examples of primary research include engaging with people and their information via social media, creating focus groups, engaging in beta-testing or prototype trials, medical and psychological studies, etc., some of which require a detailed review process.

Secondary Research

Secondary research information can be obtained from a variety of sources, some of which involve a slow publication process such as academic journals, while others involve a more rapid publication process, such as magazines (see Figure 7.3.1). Academic journals typically involve a slow publication process due to the peer review cycle. They contain articles written by scholars, often presenting their original research, reviewing the original research of others, or performing a “meta-analysis” (an analysis of multiple studies that analyze a given topic). The peer review process involves the evaluation and critique of pre-publication versions of articles, which give the authors the opportunity to justify and revise their work. Once this process is complete (it may take several review cycles and up to two years), the article is then published. This often rigorous peer review process is what helps to validate research reporting and why such articles are considered of greater reliability than unreviewed materials.

Figure 7.3.1 Examples of Popular vs Scholarly Sources (Last, 2019).1

Valid information can also be found in popular publications, however. Such publications have a more rapid publication process without peer review. Though the contents of articles published here are often of high quality, they are always the subject of extra scrutiny and skepticism when used in research because of the lack of peer oversight. In addition, such publications may have editorial boards that serve specific political, religious, economic, or social agendas, which may create a bias in the type of content offered. So be selective as to which popular publication you turn to for information.

For more information on popular vs scholarly articles, watch this Seneca Libraries video: Popular and Scholarly Resources.

Traditional academic sources: Scholarly articles published in academic journals are usually required sources in academic research; they are also an integral part of business reports. But they are not the only sources for credible information. Since you are researching in a professional field and preparing for the workplace, you will draw upon many kinds of traditional credible sources. Table 7.3.1 lists several types of such sources.

Table 7.3.1 Typical traditional academic research sources for business

| [Skip Table] |

|

| Traditional Academic Secondary Sources | Description |

|---|---|

| Academic Journals, Conference Papers, Dissertations, etc. |

Scholarly (peer-reviewed) academic sources publish primary research done by professional researchers and scholars in specialized fields, as well as reviews of that research by other specialists in the same field. For example, the Journal of Computer and System Sciences publishes original research papers in computer science and related subjects in system science; the International Journal of Business Communication is one of the most highly ranked journals in the field. |

| Reference Works—often considered tertiary sources |

Specialized encyclopedias, handbooks, and dictionaries can provide useful terminology and background information. For example, the Encyclopedia of Business and Finance is a widely recognized authoritative source. You may cite Wikipedia or dictionary.com in a business report, but be sure to compare the information to other reliable sources before use. |

| Books

Chapters in Books |

Books written by specialists in a given field usually contain reliable information and a References section that can be very helpful in providing a wealth of additional sources to investigate. For example, The Essential Guide to Business Communication for Finance Professionals by Jason L. Snyder and Lisa A.G. Frank. has an excellent chapter on presentation skills. |

| Trade Magazines and Popular Science Magazines |

Reputable trade magazines contain articles relating to current issues and innovations; therefore, they can be useful in determining what is “cutting edge,” or finding out what current issues or controversies are affecting business. Examples include The Harvard Business Review, The Economist, and Forbes. |

| Newspapers (Journalism) |

Newspaper articles and media releases offer a sense of what journalists and people in industry think the general public should know about a given topic. Journalists report on current events and recent innovations; more in-depth “investigative journalism” explores a current issue in greater detail. Newspapers also contain editorial sections that provide personal opinions on these events and issues. Choose well-known, reputable newspapers such as The Globe and Mail. |

| Industry Websites (.com) |

Commercial websites are generally intended to “sell” a product or service, so you have to select information carefully. These websites can also give you insights into a company’s “mission statement,” organization, strategic plan, current or planned projects, archived information, white papers, business reports, product details, costs estimates, annual reports, etc. |

| Organization Websites (.org) |

A vast array of .org sites can be very helpful in supplying data and information. These are often public service sites and are designed to share information with the public. |

| Government Publications and Public Sector Websites (.gov/.edu/.ca) |

Government departments often publish reports and other documents that can be very helpful in determining public policy, regulations, and guidelines that should be followed. Statistics Canada, for example, publishes a wide range of data. University websites also offer a wide array of non-academic information, such as strategic plans, facilities information, etc. |

| Patents |

You may have to distinguish your innovative idea from previously patented ideas; you can look these up and get detailed information on patented or patent-pending ideas. |

| Public Presentations |

Public consultation meetings and representatives from business and government speak to various audiences about current issues and proposed projects. These can be live presentations or video presentations available on YouTube or TED talks. |

| Other |

Can you think of some more? (Radio programs, podcasts, social media, etc.) |

You may want to check out Seneca Libraries Business Library Guide for information on various academic sources for business research information.

Business-related sources: The use of AI and other technologies such as sensors and satellites in information collection has also led to other types of information sources that may not be considered the norm, but which nonetheless offer equally valuable and credible research information. Some of these are used to collect large amounts of data (big data). Here in Table 7.3.2 is a selection of such sources (Note: Copilot and Elicit are the only approved AI tools at Seneca):

Table 7.3.2 Business-related secondary sources (CIRI, 2018; Microsoft, 2025)*

*NOTE: These non-traditional research sources are used in business and industry, but would not normally be used for academic research.

| Business-Related Secondary Sources | Description |

| Automated Searches | AI tools like Elicit and Consensus will use key words and research questions to quickly aggregate relevant academic publications available in the Semantic Scholar database. Such tools offer additional features, such as summarization, insights, and citations. ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude, and other LLM models are also being used for searches. Though their accuracy and citations are improving and vary from model to model, output must be carefully reviewed prior to use. |

| Social Media

LinkedIn, X, Blue Sky, Mastodon, Facebook Groups |

Depending on who you follow, you can find brief useable content and links to articles and other information that can be used as research sources on social media. For example, experts on LinkedIn, Blue Sky, and X often share their published research, blog posts, videos, and other materials that are then discussed by other experts. The original posts, attachments/links, and comments are all rich sources of information, but they must be carefully evaluated prior to use. |

| Alternative Media | News sources such as found in Canadian sites like Rabble and magazines like The Walrus offer timely articles on current events, politics, and social issues. A variety of alternative news sources exist that satisfy a range of political and social perspectives, both from the left and the right, so you must use a critical lens to evaluate these sources for bias. |

| Alternative Financial and Other Worlds | Cryptocurrency and metaverse (simulated worlds and gaming) data are growing sources of information for consumer behaviour, investment, game development, and financial trends. |

| Blogs | Experts in various fields post theories, research findings, and developing thinking on the latest topics in their field on blogs like WordPress or Substack or on personal websites. Be selective as blog postings usually consist of work in progress, so the thinking can change depending on what the author’s research reveals over time. |

| Online Communities | Sites like Reddit and Discord are digital communities where posts are organized according to interest areas. Carefully evaluate all information for credibility and accuracy as the posts are often opinion and experience based. |

| Crowdsourcing Platforms | Research into new products, services, and tools that are in the pre-release phases can be done by searching not only patents but also crowdsourcing platforms like Kickstarter and StackExchange. |

| Sensor and Wearable Technologies | Sensor and wearable technology data such as heart monitors, fitness sensors, diabetes monitors, car health, smart meters, and the like all aid in the collection of personal, physical, mechanical, and environmental data. |

| Mobile and Transactional Applications | Mobile apps will collect data on user behaviour, consumer preferences, and other information. Transactional technologies will capture data relating to financial, retail, consumer behaviour and preferences, and the like |

| Website and Other Internet Technologies | The internet can collect data about consumer behaviours and operations from various devices as they link to the network. Specific websites collect data on usage, page views, and consumer behaviours. Some tools will scrape the internet to collect data on competitors, market price trends, and product availability. |

| Satellite and Geolocation Technologies | Satellite data and imagery, such as gathered by Orbital Insight, can assist with geospatial information gathering that can be used areas like supply chain, real estate, as well as governance and geopolitics. Geolocation data is collected from devices that permit the gathering of information based on geographical location. SafeGraph and Placer.ai, for example, gather data and create insights relating to location, foot traffic, community context, and more to develop marketing and branding information. |

| Weather and Environmental Technologies | In the real estate, manufacturing, supply chain, aviation, and agricultural sectors, for example, instruments gather data that will provide information on weather patterns and trends, air and water quality, soil and air conditions, water levels and conditions, as well as other factors. |

Be reminded that when gathering, storing, and using data, especially that related to people’s personal information, you must abide by the Canadian federal and provincial privacy laws. Please refer to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) and Ontario’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) for more information. See more about protecting people’s information in Chapter 7.5 Research Ethics.

Knowledge Check

Deep Research Reasoners and Agents

LLMs have developed autonomous reasoning capabilities to the point that the technologies can now complete complex research, and paired with agentic technologies, they can do so autonomously (McFarland, 2025; Mollick, 2025). Open AI’s Deep Research and Google’s Deep Research, for example, are AI agents (autonomous, task-focused AI tools) that are able to produce copious and largely reliable analyses, summaries, insights, and other materials based on materials and direction provided by researchers.

The Google and OpenAI tools are not the same, however. As Alex McFarland (2025), AI Journalist, points out, the capabilities of each model differ substantially. For example, OpenAI’s Deep Research will go about the research in a less structured manner than Google’s model resulting in broader and more comprehensive research results that are reliable and of high quality (Mollick, 2025). The output reveals that the agent in OpenAI’s case, will take a more creative approach that follows information as it is revealed and takes unexpected avenues of search to reveal deep information. In addition OpenAI’s model will show its reasoning process (McFarland, 2025; Mollick, 2025). On the other hand, Google’s Deep Research uses a more structured approach that relies heavily on information provided by the user (McFarland, 2025). The output will be limited to primary information, reports, and links that are often culled from websites including paywalled sites that vary in quality and reliability (Mollick, 2025).

The kind of research you are doing will help determine what you want to pay for access. According to McFarland (2025), if you are a professional in finance, academia, or policy, for example, it would be worth it to use OpenAI’s model; on the other hand, if you are a casual user, then the Google model would be better suited for you. Be reminded that Copilot is the only approved LLM for use at Seneca and really should not be used for research purposes.

Evaluating Research Materials

Mark Twain, supposedly quoting British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, famously said, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” On the other hand, H.G. Wells has been (mis)quoted as stating, “statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write” (Quora, n.d.). The fact that the actual sources for both “quotations” are unverifiable makes their sentiments no less true. The effective use of statistics can play a critical role in influencing public opinion as well as persuading in the workplace. However, as the fame of the first quotation indicates, statistics can be used to mislead rather than accurately inform—whether intentionally or unintentionally.

The importance of critically evaluating your sources for authority, relevance, timeliness, and credibility can therefore not be overstated. Anyone can put anything on the internet; and people with strong web and document design skills can make this information look very professional and credible—even if it isn’t. Moreover, LLMs are notorious for producing content that is in accurate and often unverifiable. Since much research is currently done online, and many sources are available electronically, developing your critical evaluation skills is crucial to finding valid, credible evidence to support and develop your ideas. In fact, corroboration of information has become such a challenging issue that there are sites like this List of Predatory Journals that regularly update its online list of journals that subvert the peer review process and simply publish for profit.

When evaluating research sources, regardless of their origin (LLM or traditional research) be careful to critically evaluate the authority, content, and purpose of the material, using questions in Table 7.3.3. You should also ensure that the claims included in LLM output include source information and that you corroborate or check those sources for accuracy. For more information on evaluating sources, also view this brief Seneca Libraries video, Evaluating Websites.

And it may be tempting to use a LLM to go through the output it created to check for accuracy and bias. But why would you do that? If it created erroneous or unsupported content to begin with, you would not want it to check its own output. That’s your responsibility. Here are some tools to help you through this process.

Table 7.3.3 A question-guide for evaluations of the authority, content, and purpose of information

| [Skip Table] |

|

| Authority Researchers Authors Creators |

Who are the researchers/authors/creators? Who is their intended audience? What are their credentials/qualifications? What else has this author written? Is this research funded? By whom? Who benefits? Who has intellectual ownership of this idea? How do I cite it? Where is this source published? What kind of publication is it? Authoritative Sources: written by experts for a specialized audience, published in peer-reviewed journals or by respected publishers, and containing well-supported, evidence-based arguments. Popular Sources: written for a general (or possibly niche) public audience, often in an informal or journalistic style, published in newspapers, magazines, and websites with a purpose of entertaining or promoting a product; evidence is often “soft” rather than hard. |

|---|---|

|

Content |

Methodology What is the methodology of the study? Or how has evidence been collected? Is the methodology sound? Can you find obvious flaws? What is its scope? Does it apply to your project? How? How recent and relevant is it? What is the publication date or last update? |

|

Data Is there sufficient data to support their claims or hypotheses? Do they offer quantitative and/or qualitative data? Are visual representations of the data misleading or distorted in some way? |

|

|

Purpose |

Why has this author presented this information to this audience? Why am I using this source? Will using this source bolster my credibility or undermine it? Am I “cherry-picking” – using inadequate or unrepresentative data that only supports my position, while ignoring substantial amount of data that contradicts it? Could “cognitive bias” be at work here? Have I only consulted the kinds of sources I know will support my idea? Have I failed to consider alternative kinds of sources? Am I representing the data I have collected accurately? Are the data statistically relevant or significant? |

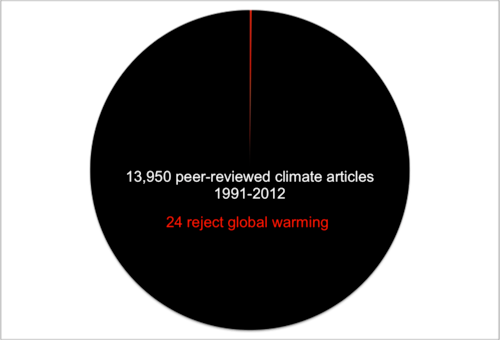

We all have biases when we write or argue; however, when evaluating sources, you want to be on the lookout for bias that is unfair, one-sided, or slanted. Here is an example: Given the pie chart in Figure 7.3.2, if you only consulted articles that rejected global warming in a project related to that topic, you would be guilty of cherry-picking and cognitive bias.

When evaluating a source, consider whether the author has acknowledged and addressed opposing ideas, potential gaps in the research, or limits of the data. Look at the kind of language the author uses: Is it slanted, strongly connotative, or emotionally manipulative? Is the supporting evidence presented logically, credibly, and ethically? Has the author cherry-picked or misrepresented sources or ideas? Does the author rely heavily on emotional appeal? There are many logical fallacies that both writers and readers can fall prey to (see Table 7.3.4 and for more information refer to Chapter 3.4 ). It is important to use data ethically and accurately, and to apply logic correctly and validly to support your ideas.

Table 7.3.4 Common logical fallacies

| [Skip Table] | |

| Bandwagon Fallacy |

Argument from popularity – “Everyone else is doing it, so we should too!” |

|---|---|

| Hasty Generalization |

Using insufficient data to come to a general conclusion. E.g., An Australian stole my wallet; therefore, all Australians are thieves! |

| Unrepresentative Sample |

Using data from a particular subset and generalizing to a larger set that may not share similar characteristics. E.g., Giving a survey to only female students under 20 and generalizing results to all students. |

| False Dilemma |

“Either/or fallacy” – presenting only two options when there are usually more possibilities to consider E.g., You’re either with us or against us. |

| Slippery Slope |

Claiming that a single cause will lead, eventually, to exaggerated catastrophic results. |

| Slanted Language |

Using language loaded with emotional appeal and either positive or negative connotation to manipulate the reader |

| False Analogy |

Comparing your idea to another that is familiar to the audience but which may not have sufficient similarity to make an accurate comparison E.g., Governing a country is like running a business. |

| Post hoc, ergo prompter hoc |

“After this; therefore, because of this” E.g., A happened, then B happened; therefore, A caused B. Just because one thing happened first, does not necessarily mean that the first thing caused the second thing. |

| Circular Reasoning |

Circular argument – assuming the truth of the conclusion by its premises. E.g., I never lie; therefore, I must be telling the truth. |

| Ad hominem |

An attack on the person making an argument does not really invalidate that person’s argument. It might make them seem a bit less credible, but it does not dismantle the actual argument or invalidate the data. |

| Straw Man Argument |

Restating the opposing idea in an inaccurately absurd or simplistic manner to more easily refute or undermine it. |

| Others? |

There are many more… can you think of some? For a bit of fun, check out Spurious Correlations. |

Please refer to Chapter 3.4 Writing to Persuade to find out how you can check your work for logical fallacies.

Knowledge Check

Critical thinking lies at the heart of evaluating sources. You want to be rigorous in your selection of evidence because, once you use it in your paper, it will either bolster your own credibility or undermine it.

Notes

- Cover images from journals are used to illustrate the difference between popular and scholarly journals, and are for noncommercial, educational use only.

References

Canadian Investor Relations Institute (CIRI).(2018) CIRI advisor – Using Non-Traditional Data for Market and Competitive Int….pdf

Government of Canada. Statistics Canada. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/start

Last, S. (2019). Technical writing essentials. BCcampus. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/

Microsoft. (2025, January 20). Non-traditional sources of information. Copilot 4o, Microsoft Enterprise Version.

McFarland, A. (2025, updated February 5). Google Gemini vs. OpenAI Deep Research: Which Is Better? – Techopedia

Mollick, E. (2025, February 3). The End of Search, The Beginning of Research

Seneca Libraries. (2013, July 2). Evaluating Websites [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/35PBCC5TKxs

Seneca Libraries. (2013, July 2). Popular and Scholarly Resources [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/wPj-BBB0le4

Seneca Libraries. (2021, January 4 updated). Writing and Communicating Technical Information: Key Resources. Seneca College. https://library.senecacollege.ca/technical/keyresources

What is the source of the H.G. Wells quote, ‘Statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write/”? (n.d.). Quora. https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-source-of-the-H-G-Wells-quote-Statistical-thinking-will-one-day-be-as-necessary-for-efficient-citizenship-as-the-ability-to-read-and-write

Wright-Tau, C. (2013). There’s No Denying It: Global Warming is Happening | Home on the Range