9.1 Correspondence Formats and Conventions

Most routine business communication occurs through brief documents known as correspondence, which includes text messages, emails, memos, and letters. These forms of communication enable employees and other stakeholders to transmit information, requests, invitations, data and many other forms of content quickly mostly through electronic media in order to accomplish daily tasks. While texting has its own conventions, emails, memos, and letters are created using standardized formats and structure that make for efficient creation and reading. For example, letters have a familiar look because of the standard components that are used to format such documents. Formats serve to do the following:

- Signal the level of formality

- Set expectations about the message and purpose of the document

- Help to create a degree of standardization in the documentation circulating within and outside of organizations

- Inform readers on how to read the document

Texting

Whatever digital device you use, brief messages or notes have become a common way to connect. Using short messaging service (SMS) also known as texting is useful for short exchanges and is a convenient way to stay connected with others when talking on the phone would be cumbersome. Texting is not useful for long or complicated messages, and careful consideration should be given to the audience. However, it has become a method for employees to keep in frequent communication regarding dynamic situations and ongoing projects.

When texting, always consider your audience and your company, and choose words, terms, or abbreviations that will deliver your message appropriately and effectively. Since not all employees are familiar with abbreviations and acronyms used in texting or comfortable with texting overall, always ask before beginning interactions using this method.

If your work situation allows or requires you to communicate via text messages, keep the following tips in mind:

- Know your recipient: “? % dsct” may be an understandable way to ask a close associate the correct discount amount that should be offered a certain customer, but if you are writing a text to your boss, it might be wiser to write, “what % discount does Murray get on $1K order?”

- Anticipate unintentional misinterpretation: Texting often uses symbols, abbreviations, and acronyms to represent thoughts, ideas, and emotions. Given the complexity of communication, and the useful but limited capacity of texting, be aware of its limitation to prevent misinterpretation. Spell it out when in doubt.

- Use appropriately: Contacting someone too frequently can border on harassment. Texting is a tool. Use it when appropriate, but don’t abuse it.

- Don’t text and drive: Research shows that the likelihood of an accident increases dramatically if the driver is texting behind the wheel (Shapely, 2020). Being in an accident while conducting company business would reflect poorly on your judgment as well as on your employer.

Knowledge Check

Email is familiar to most students and workers. It is used to send brief, routine business communications and information electronically. Over the years, it has become the primary form of communication for companies (Bovee, Thill, & Scribner, 2016, p.127) because it is rapid and inexpensive. In fact, it has largely replaced print format letters for external (outside the company) correspondence, and by-and-large has taken the place of memos for internal (within the company) communication (Guffey, 2008).

Email can be very useful for messages that have more content than a text message, but it is still best used for fairly brief messages or brief notices. It is used to send requests, confirm conversations (Writing and Communication Centre, n.d.), and to transmit documents in attachments. You may also use emails to request information about a company or organization, such as whether they anticipate job openings in the near future. In this case, you would send an email of inquiry, asking for information. Keep your request brief, introducing yourself in the opening paragraph and then clearly stating your purpose and/or request in the second paragraph. If you need very specific information, consider placing your request in list form for clarity. Conclude in a friendly way that shows appreciation for the help you will receive.

Many organizations use automated emails to acknowledge communications from the public or to remind associates that periodic reports or payments are due. You may also be assigned to “populate” a form email in which standard paragraphs are used but you choose from a menu of sentences to make the wording suitable for a particular transaction.

Email Format

Most people will recognize the similarity between memo and email formats since the email header has been modeled on the memo header.

Cc.:

Bcc.:

Subject:________________________________________________The message is then inserted here using the document design characteristics discussed in previous chapters.

The sample email below demonstrates the principles listed above.

From: Steve Jansen <sjansen@aplaccounting.com>

To: All Employees <allemployees@aplconstruction.com>

CC: Jane Singh <jsingh@aplaccounting.com>

BCC:

Date: September 12, 20XX

Subject: New Accounting Software Training

Dear Colleagues:

Please sign up for the next available Quickly Tax Books training offered free of charge by the company. Quickly Books training is a program offered to all employees who must work on the new Canadian Revenue Agency (CRA) tax submissions.

As you know, our company wants to ensure accuracy and compliance when completing business tax form submissions. Using Quickly Tax Books will allow us to complete the tax reports and submit them to the CRA without technical issues.

The training will consist of a hands-on workshop where you will be guided through the process of completing the tax forms. Complex business tax situations will be covered so that you can learn easy methods for troubleshooting them. The workshop will be led by our own Christine Althos, who has led many other previous workshops.

If you are working on this year’s business tax forms and have not as yet taken this training, please sign up for the next workshop scheduled for Friday, October 9 from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. For more information on the Quickly Tax Books training program, please visit https://www.quicklytaxbooks.co

Please let me know if you will attend by responding to this message via email.

Steve Jansen

CEO, APL Accounting, Inc.

Copied: Jane Singh, Manager, Human Resources

Guidelines for Use

Emails may be informal in personal contexts, but business communication requires attention to detail, awareness that your email reflects you and your company, and a professional tone so that it may be forwarded to any third party if necessary. Email often serves to exchange information within organizations. Although email may have an informal feel, remember that when used for business purposes, it must convey professionalism and respect. Never write or send anything that you wouldn’t want to be read in public or in front of your company president.

As with all writing, professional communications require attention to the specific writing context, and it may surprise you that even elements of form can indicate a writer’s strong understanding of audience and purpose. The principles explained here apply to the educational context as well; use them when communicating with your instructors and classroom peers.

Open with a proper salutation: Salutations demonstrate respect and avoid mix-ups in case a message is accidentally sent to the wrong recipient. Be aware of their levels of formality. Consider, for example, the difference between a salutation like “Dear Ms. Abenaki,” (external and formal in tone) and “Hi Barry,” (internal and informal).

Include a clear, brief, and specific subject line: An effective subject line helps the recipient understand the essence of the message, so make it brief, concrete, and specific. For example, “EMS software proposal attached” or “Financial specifications for project Y” inform the reader of the subject of the message. Avoid using a subject line that is too vague, like “Proposal.”

Ensure that the content is accurate: To avoid costly decisions based on inaccurate information, ensure that the content of the message is accurate. In particular, if you make use of an LLM to draft your message, ensure that you review it for accuracy and precision. Remember that the LLM will not have context-specific information; it’s up to you to add that content to the message as you are revising it. In critical communications, you should ask a colleague for a second look before sending the message.

Close with a signature: Identify yourself by creating a signature block that automatically contains your name and business contact information. You can do this using the settings in the email software.

Avoid abbreviations: An email is not a text message, and the audience may not find your wit cause to ROTFLOL (roll on the floor laughing out loud). Do not use abbreviations, acronyms, or symbols. However, some email software includes emojis, which you should use sparingly and only with trusted recipients.

Be brief: Omit unnecessary words.

Use a readable structure and format: Divide your message into brief paragraphs for ease of reading. A readable email should get to the point and conclude in three small paragraphs or less. Use this basic structure for multi-paragraph messages: Open with the purpose statement and background, add details/explanation, end with a courteous close or an action request.

Reread, revise, and review: Catch and correct spelling and grammar mistakes before you press “send.” It will take more time and effort to undo the problems caused by a hastily and poorly written email than to take the time to get it right the first time. Some email software makes this process easy by flagging errors.

LLMs can be helpful in the review process. If your message does not contain confidential or private information, you can upload your document to the LLM with a request for it to give you feedback on areas needing improvement.

Reply promptly: Watch out for your own emotional response—never reply in anger—but make a habit of replying to all emails within 24 hours, even if only to say that you will provide the requested information the next day.

Follow up: If you don’t get a response in 24 hours, email or call. Spam filters may have intercepted your message, so your recipient may never have received it. In pressing situations, you can resend your message with an “In case you missed it. . .” opening, showing that you understand that your recipient may be busy to the point of having missed your message. Be sparing in your follow ups. If you do not receive an immediate reply, you simply may have to wait.

Use “Reply All” sparingly: Do not send your reply to everyone who received the initial email unless your message absolutely needs to be read by the entire group.

Avoid using all caps: Capital letters are used on the Internet to communicate emphatic emotion or yelling and are considered rude.

Test links: If you include a link, test it to make sure it is working. You can do this by sending yourself a test message.

Consider file size and options: Audio and visual files are often quite large; avoid exceeding the recipient’s mailbox limit or triggering the spam filter. If your file is of an excessive size, upload it to cloud storage and share the file using a link.

Tip: Add the address of the recipient last to avoid sending your message prematurely. This will give you time to do a last review of what you’ve written, make sure links work and that you’ve added the attachment, etc., before adding the sender’s address and hitting Send.

This following video by Indeed Career Tips offers up-to-date effective strategies on how to compose a professional email.

(Email Etiquette: Tips for Professional Communication in the workplace, 2022)

Check out the University of Waterloo’s Writing Professional Emails in the Workplace for more information.

Knowledge Check

When organizing the content for a lengthy email, use the message structure described below for memos: opening and background, details, and action close.

Memos

Memoranda, or memos, were once the most versatile document forms used in professional settings; however, they have largely been replaced by emails. Memos are “in-house” documents (sent within an organization) to pass along or request information, outline policies, present short reports, and propose ideas. While they are often used to inform, they can also be persuasive documents. A company or institution typically has its own “in-house” style or template that is used for documents such as letters and memos. Nowadays, memos are used when signatures are required, to elevate the importance of a message, or to facilitate storage in a computer file (since it is most often transmitted as an email attachment.

Memo Format

The Header Block appears at the top left side of your memo, directly underneath the word MEMO or MEMORANDUM in large, bold, capitalized letters. This section contains detailed information on the recipient, sender, and purpose. It includes the following lines:

TO: Give the recipient’s full name, and position or title within the organization

FROM: Include the sender’s (your) full name and position or title

DATE: Include the full date on which you sent the memo

SUBJECT: Write a brief phrase that concisely describes the main content of your memo.

Place a horizontal line under your header block, and place your message below.

Memos look much like emails and are characterized by a simple header formatted as follows:

MEMORANDUM

To:

From:

Date:

Subject:

___________________________________________

The message is then inserted here using the document design characteristics discussed in previous chapters.

In the “From:” field, handwrite your initials after your typed name to authenticate the document if you are to print the memo for distribution. In the “Subject” line, you would include a brief phrase announcing the subject in a concrete and specific way. See the above Guidelines for Effective Professional Emails for more information about subject lines.

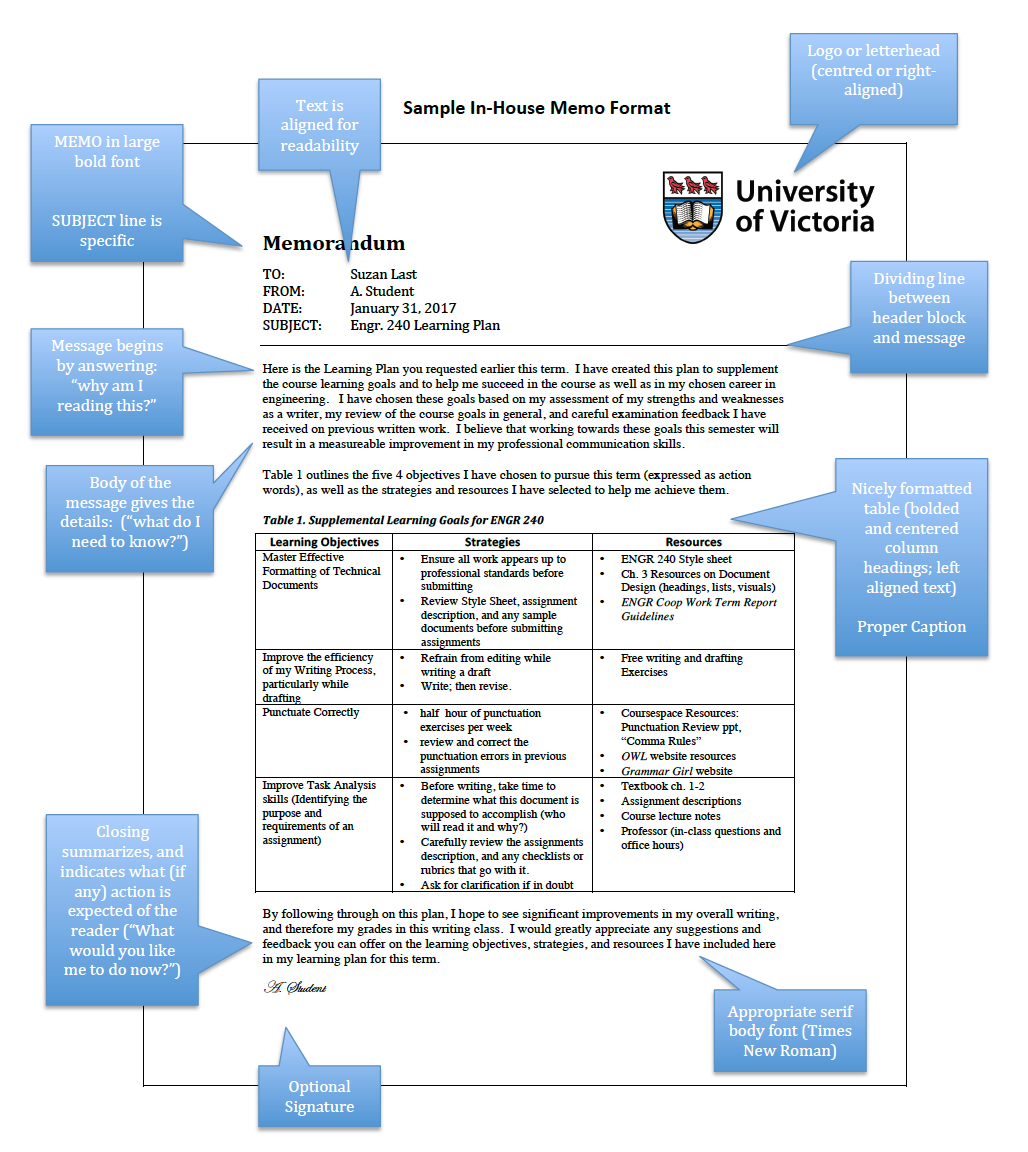

Figure 9.1.1 shows a sample of an “in-house” memo style, with annotations pointing out various relevant features. The main formatted portions of a memo are the Logo or Letterhead (optional), the Header Block, and the Message. The attached Memos PowerPoint reviews some of these features in detail.

Asking an LLM to Create a Memo Format

Use the following direction in your prompt to ask the LLM to format your document in a memo format:

Prompt: Help me to format this document as a memo. I want to include the following elements in the header: To:, From:, Date:, Subject:. Organize these in the appropriate place on the page. Also add a line below the header to separate the header from the message.

Memo Message Structure

The length of a memo can range from a few short sentences to a multi-page report that includes figures, tables, and appendices. Whatever the length, there is a straightforward organizational principle you should follow. Organize the content of your memo so that it answers the following questions for the reader (this structure also applied to email messages):

- Opening and background: Why do I have to read this and what are the circumstances leading to this message?

- Details: What do I need to know?

- Closing: What am I expected to do now?

Memos (and most emails) are generally very direct and concise. There is no need to start with general introductions before getting to your point. Your readers are colleagues within the same organization and are likely familiar with the context in which you are writing. Think of the message as building blocks:

This structure applies to longer email messages as well as letters. For more information on writing memos, check out the memo page on the Online Writing Lab at Purdue University: Parts of a Memo. Examples of various types of correspondence follow in the upcoming chapters.

Knowledge Check

Asking an LLM to Organize Information for Memos and Email

For memos and emails that convey information or make requests, you can use the following direction in your prompt to ask the LLM to help you organize the draft message according to conventions:

Prompt: Help me to organize the contents of the message according to business conventions by giving me some feedback on how I can include the following:

Opening and background: An opening that includes a main message or purpose statement, and background information that sets the context for the reader.

Details: Include the details I’ve included in this prompt [your prompt would contain specific detail that should be in the message.]

Closing: End on a friendly but professional note that builds good will and informs the reader about what they are supposed to do (if anything is to be done).

Letters

Letters are brief messages sent to recipients that are often outside the organization. They are often created using company letterhead templates and are generally limited to one or two pages. While email and text messages may be used more frequently today, the business letter remains a common form of written communication for formal, external matters. It can serve to introduce you to a potential employer, convey a project estimate to a client or partner, or announce or market a product or service, for example. Often, the letter format is used for short reports when more substantial information, like site observations, must be conveyed to an external party.

There are many types of letters, and many adaptations in terms of form and content.

This section covers the elements of a traditional block-style letter. Letters may serve to introduce your skills and qualifications to prospective employers (cover letter), deliver important or specific information, document an event or decision, or introduce an attached report or long document (letter of transmittal). Figure 9.1.2 shows a basic letter of transmittal meant to introduce a report to its recipient. Often, writers will include a paragraph acknowledging key individuals who have provided assistance.

James Singh

123 Anywhere Street

Toronto, ON M1X 1X1

March 15, 20XX

Ms. Kitty Hawk, Administrator

XYZ Company

456 Anywhere Street

Toronto, ON M0L 0L0

Dear Ms. Hawk:

As requested, please find enclosed the report titled “Diversity Initiatives in Thriving Canadian Organizations.” This report provides a comprehensive analysis of diversity initiatives within Canadian organizations and discusses their impact on organizational performance and culture.

The report offers an in-depth overview of diversity initiatives implemented across business sectors in Canada. It discusses the benefits of fostering a diverse and inclusive workplace, including enhanced creativity, breadth of information and perspectives, improved employee satisfaction, and better decision-making processes. The report also addresses the challenges organizations face in implementing these initiatives and provides recommendations for overcoming these obstacles.

Our findings have led to the following key conclusions:

- Diversity programs importantly contribute to a positive organizational culture by promoting respect and inclusion among employees.

- Organizations with strong diversity initiatives enjoy better financial performance and higher employee retention.

- The most successful diversity programs have ongoing commitment from leaders and follow a continuous improvement process.

I hope the insights and recommendations in this report will prove to be valuable additions to your organization’s diversity and inclusion efforts. Please do not hesitate to contact me if you would like to discuss any of the information presented in the document.

Thank you for your time and consideration.

Sincerely,

James Singh, Diversity Specialist

Encl.

LLM Declaration: This example has been created with the assistance of Copilot, using the following prompt on March 13, 2025:

Craft a letter of transmittal for a report on the importance of diversity initiatives in Canadian organizations. The transmittal letter must have a clear transmittal statement, overview of the report including conclusions, a courteous close.

Figure 9.1.2 Sample letter of transmittal (Co-created with Copilot, March 15, 2025)

A typical letter format has ten main parts:

- Letterhead/logo: Sender’s name and return address; often includes the company name and logo

- Date: Written in full

- The receiver’s block: Name, position, company, and address of the recipient

- Salutation: “Dear ______: ” use the recipient’s name, if known; use a colon for punctuation (this differs from email salutations which require a less formal comma). A common salutation may be “Dear Mr. (full name).” If you are unsure about titles (i.e., Mrs., Ms., Mr., Mx., Dr.), you may simply write the recipient’s name (e.g., “Dear Cameron Rai”) followed by a colon. The salutation “To whom it may concern” is appropriate for letters of recommendation or other letters that are intended to be read by any and all individuals. If this is not the case with your letter, but you are unsure of how to address your recipient, make every effort to find out to whom the letter should be specifically addressed. Avoid the use of impersonal salutations like “Dear Prospective Customer,” as the lack of personalization can alienate a future client.

- The introduction: Establishes the overall purpose of the letter. This is your opening paragraph, which may include an attention statement, a reference to the purpose of the document, and an introduction of the person or topic depending on the type of letter. An emphatic opening involves using the most significant or important element of the letter in the introduction. Readers tend to pay attention to openings, and it makes sense to outline the expectations for the reader up front. Just as you would preview your topic in a speech, the clear opening in your introductions establishes context and facilitates comprehension.

- The body: Articulates the details of the message: your explanation, a series of facts, or a number of questions belong in the body of your letter. Readers may skip over information in the body of your letter, so make sure you emphasize the key points clearly. You may choose organizational devices to draw attention, such as a bullet or numbered list. The body contains your core content, but brevity is important and so is clear support for the main point(s). Specific, meaningful information needs to be clear, concise, and accurate.

- The conclusion: Restates the main point and may include a call to action. It definitely should end with good will. An emphatic closing mirrors your introduction with the added element of tying the key points together, clearly demonstrating their relationship. The conclusion can serve to remind the reader, but should not introduce new information. A clear summary sentence will strengthen your writing and enhance your effectiveness. If your letter requests or implies action, the conclusion needs to make clear what you expect to happen. This paragraph reiterates the main points and their relationship to each other, reinforcing the main point or purpose.

- The signature block: Include a complimentary close like “Sincerely,” and about 4 line spaces for the signature, the sender’s name and role, along with company email address and phone extension. “Sincerely” or “Cordially” are standard business closing statements. Closing statements are normally placed one or two lines under the conclusion and include a hanging comma, as in “Sincerely,”. If you are creating your letter in an email message box, you do not need to include the 4 line spaces below “Sincerely.” Simply include your name right below that word.

- Enclosure note: Just like an e-mail with an attachment, the letter sometimes has additional documents that are delivered with it. The Enclosure line indicates what the reader can look for in terms of documents included with the letter, such as brochures, reports, or related business documents. Only include this note if you are in fact including additional documentation. The enclosure note can be non-specific as in “Encl.” or it can be more specific by including a list of enclosed or attached documents.

- Complementary copies: The abbreviation “CC” once stood for carbon copies but now refers to complementary copies. Just like a “CC” option in an e-mail, it indicates the relevant parties that will also receive a copy of the document.

Keep in mind that letters represent you and your company in your absence. In order to communicate effectively and project a positive image, remember that

- your language should be clear, concise, specific, and respectful,

- each word should contribute to your purpose,

- each paragraph should focus on one idea,

- the parts of the letter should form a complete message, and

- the letter should be free of errors.

Asking an LLM to Format a Letter

Use the following direction in your prompt to ask the LLM to format your document as a letter:

Prompt: Help me to format this document as a letter. I want to include the standard components of the letter header, including the following: Return Address, Date, Inside Address, Subject.

Knowledge Check

Letters with Specific Purposes

Letters within the professional context may take on many purposes, such as communicating with suppliers, partner organizations, clients, government agencies, and so on. In business, you may write letters for many possible reasons. Below is a list of the most common kinds of letters:

Transmittal Letters: When you send a report or some other document, such as a resumé, to an external audience, send it with a cover letter that contains a brief explanation of the purpose of the enclosed document and a summary of the document’s contents. Click the link to download a Letter-of-Transmittal-Template.

Letters of Confirmation: In certain formal circumstances such as in the case of a job offer or a formal invitation, it is customary to follow up with a message of confirmation formatted as a letter. You may send the letter attached to a brief email transmittal message. Using a separate letter signals your awareness of the context and shows your ability to adapt messages for specific situations.

Recommendation Letters: You will often during the course of your career be asked to send letters of recommendation for colleagues with whom you have worked or whom you have supervised. Such letters are typically attached to a brief email transmittal message sent to your colleague’s potential new employer. Sometimes these letters are required for your colleague’s grant applications. Such letters are often a pleasure to write as they are opportunities to highlight the many strengths demonstrated by your colleague when working with you.

Information in this chapter was partially adapted from the following sources:

“Professional Communications” chapter in Technical Writing by Annemarie Hamlin, Chris Rubio, Michele DeSilva, and “Writing Letters” in Business Writing for Everyone by Arly Cruthers. These sources are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

References

Bovee, C.L., Thill, J.V., & Scribner, J.A. (2016). Business communication essentials. 4th Canadian Edition. Toronto: Pearson Education, p. 127.

Cruthers, A. (2020). Writing letters. Business writing for everyone. https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/businesswriting/chapter/writing-letters/

[Email icon]. https://www.iconfinder.com/icons/4417125/%40_email_envelope_letter_icon. Free for commercial use.

Guffey, M. (2008). Essentials of business communication (7th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Hamlin, A., Rubio, C., & DeSilva, M. Technical writing. https://coccoer.pressbooks.com/chapter/professional-communications/. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

Indeed. (2022). Email Etiquette: Tips for professional communication in the workplace [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3eLzpJcst5Y

Khan, Md. M. (2015, December 20). Email etiquette. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/email-etiquette-mamun-khan

Shapley, J. (2020, March 18). Distracted driving can be deadly. Put down the phone. The Houston Chronicle. https://www.houstonchronicle.com/opinion/editorials/article/Distracted-driving-can-be-deadly-Put-down-the-15137381.php

[Texting image]. https://www.flickr.com/photos/13604571@N02/2094946972. CC BY-NC 2.0.Writing and Communication Centre. (n.d.). Writing Professional emails in the workplace. University of Waterloo. https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/resources-writing-professional-emails-workplace