3.3 Communicating with Precision

So far we have discussed the importance of writing with the reader in mind; of striking the right tone for your audience, message, and purpose; of writing constructively; and of the importance of inclusive communication. Two additional key characteristics of professional communication are precision and conciseness. This precision and concision must be evident at all levels, from the overall document, to paragraphing, to sentence structure to word choice, and even to punctuation. Every word or phrase should have a distinct and useful purpose. If it doesn’t, cut it or revise.

Though some LLM models are improving, overall LLMs notoriously produce content that lacks precision and concision. Their outputs often do the following:

- Create redundancies: The output often contains statements that are restated multiple times but using different words.

- Include irrelevant information: The output will often include information that does not pertain to the context or situation you have described in your prompt.

- Made up “facts”: The output will express what appear to be facts but which are incorrect or outright false

For these reasons, routinely engaging in a careful review of the information contained in the outputs is necessary. Below you will discover how to edit both your own and LLM output to achieve accuracy and precision in your writing.

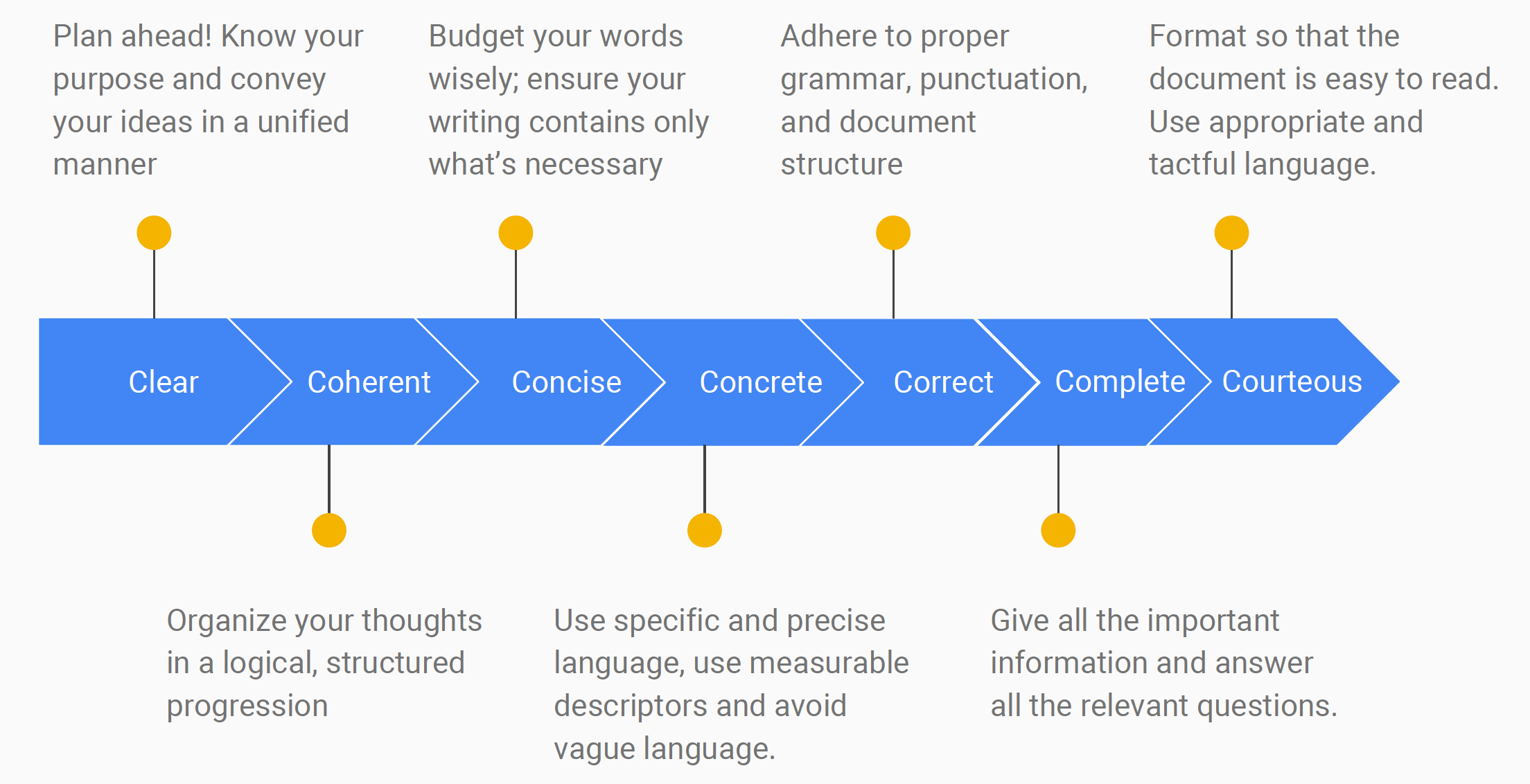

The 7 Cs of Professional Writing

The 7 Cs are simply seven words that begin with C that characterize a strong professional style. Applying the 7 Cs of professional communication will result in writing that is

- Clear

- Coherent

- Concise

- Concrete

- Correct

- Complete

- Courteous

CLEAR writing involves knowing what you want to say before you say it because often a lack of clarity comes from unclear thinking or poor planning; this, unfortunately, leads to confused or annoyed readers. Clear writing conveys the purpose of the document immediately to the reader; it matches vocabulary to the audience, avoiding jargon and unnecessary specialized or obscure language while at the same time being precise. In clarifying your ideas, ensure that each sentence conveys one idea, and that each paragraph thoroughly develops one unified concept.

COHERENT writing ensures that the reader can easily follow your ideas and your train of thought. One idea should lead logically into the next through the use of transitional words and phrases, structural markers, planned repetition, sentences with clear subjects, headings that are clear, and effective and parallel lists. Writing that lacks coherence often sounds “choppy” and ideas seem disconnected or incomplete. Coherently connecting ideas is like building bridges between islands of thought so the reader can easily move from one idea to the next.

CONCISE writing uses the least words possible to convey the most meaning while still maintaining clarity. Avoid unnecessary padding, awkward phrasing, overuse of “to be” forms (is, are, was, were, am, be, being), long preposition strings, vagueness, unnecessary repetition and redundancy. Use active verbs whenever possible, and take the time to choose a single word rather than a long phrase or cliched expression. Think of your word count like a budget; be cost-effective by making sure every word you choose does effective work for you. Cut a word, save a buck! As William Zinsser (1980) asserts, “the secret of good writing is to strip every sentence to its cleanest components.”

CONCRETE writing involves using specific, precise language to paint a picture for your readers so that they can more easily understand your ideas. If you have to explain an abstract concept or idea, try to use examples, analogies, and precise language to illustrate it. Use measurable descriptors whenever possible; avoid vague terms like “big” or “good.” Try to get your readers to “see” your ideas by using specific terms and descriptions. For example, when describing an amount use actual values like 0.1 ml or 250 grams.

CORRECT writing uses standard English punctuation, sentence structure, usage, and grammar. Being correct also means providing accurate information, as well as using the right document type and format for the task. Ensuring that your document is correct will obviously help to avoid misinterpretation and costly errors. It is also a sign of respect for your audience in that you have taken the time to review and polish your work.

COMPLETE writing includes all requested information and answers all relevant questions–as well as anticipated questions. The more concrete and specific you are, the more likely your document will be complete and useful. Review your checklist of specifications before submitting your document to its intended reader.

COURTEOUS writing entails designing a reader-friendly, easy-to-read document; using tactful language and appropriate modes of addressing the audience; and avoiding potentially offensive terminology, usage, and tone. As we have discussed in an early section, without courtesy you cannot be constructive.

In some cases, some of these might come into conflict: what if being too concise results in a tone that sounds terse or an idea that seems incomplete? In such a situation, you have the flexibility to adapt the language to suit the circumstances.

Figure 3.3.1 illustrates one method of putting all the 7Cs together.

Be mindful of the tradeoffs, and always give priority to being clear: Writing that lacks clarity cannot be understood and therefore cannot achieve its purpose. Writing that adheres to the 7 Cs helps to establish your credibility as a business professional.

Knowledge Check

Exercise: Revise for clarity

Remember the librarian’s “garbled memo” from the Case Studies in Chapter 1.4? Try revising it so that it adheres to the 7 Cs; make it clear, coherent, concrete and concise, while also being complete, courteous and correct.

MEMO

When workloads increase to a level requiring hours in excess of an employee’s regular duty assignment, and when such work is estimated to require a full shift of eight (8) hours or more on two (2) or more consecutive days, even though unscheduled days intervene, an employee’s tour of duty shall be altered so as to include the hours when such work must be done, unless an adverse impact would result from such employee’s absence from his previously scheduled assignment.

Sentence Variety and Length

While variety makes for interesting writing, too much of it can also reduce clarity and precision. Business writing tends to use simple sentence structures more often than the other types. That said, simple does not necessarily mean “simplistic,” short, or lacking in density. Remember that in grammatical terms, simple just means that it has one main clause (one subject and one predicate). You can still convey quite a bit of concrete information in a simple sentence.

The other consideration for precise writing is length. Your sentences should vary in length just as they can vary in type. However, avoid having too many long sentences because they take longer to read and are often more complex, which is appropriate in academic writing but less so in business writing. The goal is to aim for an average of around 20 to 30 words per sentence. Reserve the short sentences for main points, and use longer sentences for supporting points that clarify or explain relationships. If you feel the sentence is too long, break it into two sentences. You don’t want your reader to have to read a sentence twice to understand it. If you make compound or complex sentences, ensure that you use appropriate coordinating or subordinating strategies to make the relationship between clauses perfectly clear. See Appendix C for information on simple, compound, and complex sentence structures.

Precise Wording

Business writing is precise writing. Vague, overly general, hyperbolic or subjective/ambiguous terms are simply not appropriate in this genre. You do not want to choose words and phrasing that could be interpreted in more than one way. For example, if you asked someone to define what makes a “good dog,” you might get responses like “obedient, effective hunter/retriever, well-behaved, affectionate, loyal, therapeutic, goofy” and “all dogs are good!” Choose words that most precisely, concisely, and accurately convey the idea you want to convey. Below are some guidelines and examples to follow for using precise wording.

Replace Abstract Nouns with Verbs

Verbs, more than nouns, help convey ideas concisely, so where possible, avoid using nouns derived from verbs. Often these abstract nouns end in –tion and –ment. See examples in the following chart.

| Abstract Noun | Verb |

| acquisition | acquire |

| analysis | analyze |

| recommendation | recommend |

| observation | observe |

| application | apply |

| confirmation | confirm |

| development | develop |

| ability | able, can |

| assessment | assess |

For example, change the noun into a verb as follows:

Instead of: The inspector made the recommendation for the secure disposal of sensitive documents.

Use: The inspector recommended the secure disposal of sensitive documents.

The second sentence is clearer and more concise than the first.

Knowledge Check

Prefer Short Words to Long Words and Phrases

The goal is to communicate directly and plainly so use short, direct words whenever possible. In other words, don’t use long words or phrases when short ones will do. Write to express, not impress.

| Long | Short |

| cognizant; be cognizant of | aware, know |

| commence; commencement | begin, beginning |

| utilize; utilization | use (v), use (n) |

| inquire; make an inquiry | ask |

| finalize; finalization | complete, end |

| afford an opportunity to | permit, allow |

| at this point in time | now, currently |

| due to the fact that | because, due to |

| has the ability to | can |

Knowledge Check

Avoid Clichés

Clichés are expressions that you have probably heard and used hundreds of times. They are overused expressions that have largely lost their meaning and impact.

| Clichés | Alternatives |

| as plain as day | plainly, obvious, clear |

| ballpark figure | about, approximately |

| few and far between | rare, infrequent |

| needless to say | of course, obviously |

| last but not least | finally, lastly |

| as far as ___ is concerned | ? |

Avoid Cluttered Constructions

This category includes redundancies, repetitions, and “there is/are” and “it is” constructions.

| Redundancies | ||

| combine/join |

fill |

unite |

| finish |

refer/return/revert |

emphasize/stress |

| examine (closely) | ||

| rely/depend |

||

| plan |

protest |

|

| estimate/approximate |

gather/assemble |

|

| years |

||

| in |

||

Regarding “there are/is” or “it is” sentence constructions–the general rule is to avoid beginning sentences with these words since they do not contain information. Rather, begin with information words as follows:

Instead of: There are five computer monitors that need replacing.

Use: Five computer monitors need replacing.

This second sentence is much more concise and clear than the previous one.

Use Accurate Wording

Sometimes this requires more words instead of fewer, so do not sacrifice clarity for concision. Make sure your words convey the meaning you intend. Avoid using words that have several possible meanings; do not leave room for ambiguity or alternate interpretations of your ideas. Keep in mind that readers of business messages tend to choose literal meanings, so avoid figurative language that might be confusing (for example, using the word “decent” to describe something you like or think is good). Separate facts from opinions by using phrases like “we recommend,” “we believe,” or “in our opinion.” Use consistent terminology rather than looking for synonyms that may be less precise.

Qualify statements that need qualifying, especially if there is the possibility for misinterpretation. Do not overstate through the use of absolutes and intensifiers. Avoid overusing intensifiers like “extremely,” and avoid absolutes like “never, always, all, none” as these are almost never accurate. Remember Obiwan Kenobi’s warning:

“Only a Sith deals in absolutes.” (Lucas, 2005)

We tend to overuse qualifiers and intensifiers, so below are some that you should be aware of and consider whether you are using them effectively.

| Overused Intensifiers | |||||

| absolutely | actually | assuredly | certainly | clearly | completely |

| considerably | definitely | effectively | extremely | fundamentally | drastically |

| highly | in fact | incredibly | inevitably | indeed | interestingly |

| markedly | naturally | of course | particularly | significantly | surely |

| totally | utterly | very | really | remarkably | tremendously |

| Overused Qualifiers | |||||

| apparently | arguably | basically | essentially | generally | hopefully |

| in effect | in general | kind of | overall | perhaps | quite |

| rather | relatively | seemingly | somewhat | sort of | virtually |

For a comprehensive list of words and phrases that should be used with caution, see Kim Blank’s “Wordiness, wordiness, wordiness list” (2015).

Knowledge Check

Prefer the Active Voice

The active voice emphasizes the person/thing doing the action in a sentence. For example, The outfielder throws the ball. The subject, “outfielder” actively performs the action of the verb “throw.” The passive voice emphasizes the recipient of the action. In other words, something is being done to something by somebody: The ball was thrown (by the outfielder). Passive constructions are generally wordier and often leave out the person/thing doing the action.

| Active | Passive |

| S →V →O | S ←V ←O |

| Subject → actively does the action of the verb → to the object of the sentence | Subject ← passively receives the action of the verb ← from the object |

| Subject → acts → on object

Example: Bineshii submitted the report. |

Subject ← is acted upon ← by the object

Example: The report was submitted by Bineshii. |

Whenever possible, use the active voice to convey who or what performs the action of the verb. The active voice is used most of the time in business communication because it is a clear, direct, and concise way of conveying ideas. It is appropriate, however, to use the passive voice when you want to distance yourself from the message, such as when delivering negative news. While the passive voice has a place—particularly if you want to emphasize the receiver of an action as the subject of the sentence or the action itself, or if you do not know who is performing the action, or if you want to avoid using the first person—its overuse results in writing that is wordy, vague, and stuffy.

Precise writing encapsulates many of the 7 Cs; it is clear, concise, concrete, and correct. But it is also accurate and active. To write precisely and apply the 7 Cs, look critically at your sentences, perhaps in a way you may not have done before: Consider the design of those sentences, from the words to the phrases to the clauses, to ensure that you are communicating your message effectively.

Asking a LLM to Check for Style

You can ask the LLM to check your work so that it contains effective business style. Do the following:

- Upload or paste your text into the LLM

- Include the following in your prompt:

Prompt: . . . Read through the text that has been provided. Check my work to ensure that it meets the standards for business style, including precise words, use of the active voice, and the 7 Cs (concise, clear, complete, courteous, concrete, correct, and coherent). Please guide me on specific ways that I can make improvements.

The Importance of Verbs

Much of the style advice given so far revolves around the importance of verbs. Sentences can function efficiently or inefficiently, and the use of a strong verb is one way to make them work effectively. Here are some key principles regarding the effective use of verbs in your sentences. While effective sentences may occasionally deviate from the suggestions in this list, try to follow these guidelines as often as possible:

- Keep the subject and the verb close together; avoid separating them with words or phrases that could create confusion.

- Place the verb near the beginning of the sentence (and close to the subject).

- Maintain a high verb/word ratio in your sentence.

- Opt for active verb constructions over passive ones.

- Avoid “to be” verbs (am, is, are, was, were, being, been, be).

- Try to turn nominalizations (abstract nouns or -tion words) back into verbs.

Use the verb strength chart in Table 3.3.1 as a guide to “elevate” weaker verbs (or words with implied action) in a sentence to stronger forms.

| [Skip Table] | ||

| Verb Forms | Verb Strength | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Command/Imperative |

STRONG

WEAK |

Edit the report thoroughly Communicate respectfully in the workplace. |

| Active Indicative*

(S → V) |

He edits reports regularly. She consistently communicates respectfully. |

|

| Active conditional |

He would edit the reports if she would let him. She would communicate respectfully if she had more training. |

|

| Gerunds ( __ -ing)

Infinitives (to ___) (these do not function as verbs in your sentence; actual verbs are highlighted in yellow) |

While editing reports, he gets quite tired. Communicating effectively takes skill. It takes a lot of time to edit reports. To communicate respectfully, one must get a sense of the audience. |

|

| Passive (S ← V)

Passive Conditional |

Reports are edited by him. The report would be edited by him if… The report was written by him. Reports would be written by him if… |

|

| Nominalizations (verbs turned into abstract nouns)

Participles (nouns or adjectives that used to be verbs) |

Report writing is thoughtful work. A well-written report is a thing of beauty. Written work must be free of errors. |

|

While you are not likely to use the command form very often, unless you are writing instructions, the second strongest form, Active Indicative, is the one you want to use most often (say, in about 80% of your sentences).

Knowledge Check

Part of the skill of using active verbs lies in choosing the verbs that precisely describe the action you want to convey. Many have gotten in the habit of choosing a small selection of verbs most (to be, to do, to get, to make, to have, to put); as a result, these often-used verbs have come to have so many possible meanings that they are almost meaningless. Try looking up “make” or “have” in the dictionary; you will see pages and pages of possible meanings! Whenever possible, avoid these bland verbs and use more precise, descriptive verbs, as indicated in Table 3.3.2.

| [Skip Table] |

|

| Bland Verbs | Descriptive Verbs |

|---|---|

|

Signal Verbs: Says |

Describe the rhetorical purpose behind what the author/speaker “says”: Explains, clarifies |

|

Is, are, was, were being been Is verb-ing |

Instead of indicating what or how something “is,” describe what it DOES, by choosing a precise, active verb. Replace progressive form (is ___ing) with the indicative form She is describing → She describes |

|

Get, gets |

Usually too colloquial (or passive); instead you could use more specific verbs such as Become, acquire, obtain, receive, prepare, achieve, earn, contract, catch, understand, appreciate, etc. |

|

Do, does |

Avoid using the emphatic tense in formal writing: It does work → it works. I do crack when I see apostrophe errors → I crack when I see apostrophe errors. Instead: Perform, prepare, complete, etc. |

|

Has, have Has to, have to |

This verb has many potential meanings! Try to find a more specific verb that “have/has” or “has to”:

Instead of “have to” try: Must, require, need, etc. |

|

Make |

Build, construct, erect, devise, create, design, manufacture, produce, prepare, earn, etc. Make a recommendation → recommend |

For more detailed information on using signal verbs when introducing quotations, see Chapter 8.2: Integrating Source Evidence into Your Writing.

Knowledge Check

Exercise: Improve the following sentences by elevating the verb and cutting clutter

- Market share is being lost by the company, as is shown in the graph in Figure 3.

- A description of the product is given by the author.

- An investigation of the incident has been conducted by her.

- His task is regional database systems handbook preparation.

- While a recommendation has been made by the committee, an agreement to increase the budget will have to be approved by the committee.

Exercise: Revision practice

The following paragraph on The Effects of Energy Drinks does not conform to the 7 Cs and contains far too many “to be” verbs. Revise this paragraph so that it has a clear topic sentence, coherent transitions, correct grammar, and concise phrasing. In particular, try to eliminate all “to be” verbs (am, is, are, was, were, being, been, be), and rephrase using strong, descriptive, active verbs. The first 7 are highlighted for you. Try to cut the word count (260) in half.

After trying the exercise, click on the link below to compare your revision to effective revisions of this passage done by other students:

Sample Revisions of Exercise 3.3.3 (.docx)

Table 3.3.3 sums up many key characteristics of effective professional style that you should try to avoid (poor style) and implement (effective style) while writing business documents.

| Poor Style | Effective Style |

|---|---|

| Low VERB/WORD ratio per sentence | High VERB/WORD ratio per sentence |

| Excessive ‘is/are’ verbs | Concrete, descriptive verbs |

| Excessive passive verb constructions | Active verb constructions |

| Abstract or vague nouns | Concrete and specific nouns |

| Many prepositional phrases | Few prepositional phrases |

| Subject and verb are separated by words or phrases | Subject and verb are close together |

| Verb is near the end of the sentence | Verb is near the beginning of the sentence |

| Main idea (subject-verb relationship) is difficult to find | Main idea is clear |

| Sentence must be read more than once to understand it | Meaning is clear the first time you read it |

| Long, rambling sentences | Precise, specific sentences |

Knowledge Check

The characteristics discussed in this chapter will help you to create messages and documents that help the reader to focus on the information and reduce the risk of misunderstandings and mistakes.

References

Blank, K. G. (2015, November 3). Wordiness list. Department of English, University of Victoria. http://web.uvic.ca/~gkblank/wordiness.html

Lucas, G. (Director). (2005). Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith. [Film].

Zicari, A. & Hildemann, J. Figure 2.2.1. Used with permission.

Zinsser, W. (1980). Simplicity. http://www.geo.umass.edu/faculty/wclement/Writing/zinsser.html