6.3 Collaborative Writing

Suzan Last; Candice Neveu; and Robin L. Potter

An important part of planning for collaborative writing is to make decisions on how the team will work to create the deliverable, which often consists of an analysis of results of research that are conveyed using a report, presentation, or some other form of documentation. These decisions are already challenging to make given that you must plan for coordinating drafts and documentation, decide which strategies to use to create the final product, and confirm the roles various team members should take on so as to draw effectively on expertise and strengths.

With the increasing use of genAI in the workplace, including in teams, an additional decision must be made: To what extent will the team allow for genAI assistance in the workflow such as during the planning phase (exploration, brainstorming, outlining) as well as when creating content (outlining, drafting, revisions) for the final deliverable? And what kind of oversight will the team enforce so as to ensure a quality deliverable? There is no doubt that the technology can assist with many facets of the team coordination (as discussed in Chapter 6.1), and it can also greatly facilitate the production of content. However, and depending on the business or industry in which you find yourself, use of AI-generated content can have serious implications on business success, your own and organizational credibility, as well as safety, in some cases. Making well-reasoned decisions based on consensus on how you will integrate genAI technologies into your team’s workflow can lead to success (for more on workflow and genAI, see Chapter 2.6).

Recent surveys give us some insights into the importance of effective communication in the smooth functioning of teams. The results obtained from BIT.AI (2020) shown below indicate that collaborative writing makes up a significant portion of overall writing tasks.

86% of employees and executives cite lack of collaboration or ineffective communication for workplace failures (Salesforce).

33% of millennials want collaborative work spaces (Mercer).

37% of employees say “working with a great team” is their primary reason for staying (Gusto).

33% of employees say the ability to collaborate makes them more loyal (The Economist).

14% of the McKinsey employee workweek is spent on communicating and collaborating internally (McKinsey).

Like any kind of teamwork, collaborative writing requires the entire team to be focused on a common objective; according to Lowry et al., an effective team “negotiates, coordinates, and communicates during the creation of a common document” (2004). The collaborative writing process, like the Tuckman team formation model, is iterative and social, meaning the team works together and moves back and forth throughout the process. Many collaboration platforms exist that facilitate the collaborative writing process. Such platforms often include project folders and applications, such as SMS, timelines, work logs and tracking, and the like. Whatever technology you use to support your team’s work, however, nothing replaces good planning.

Knowledge Check

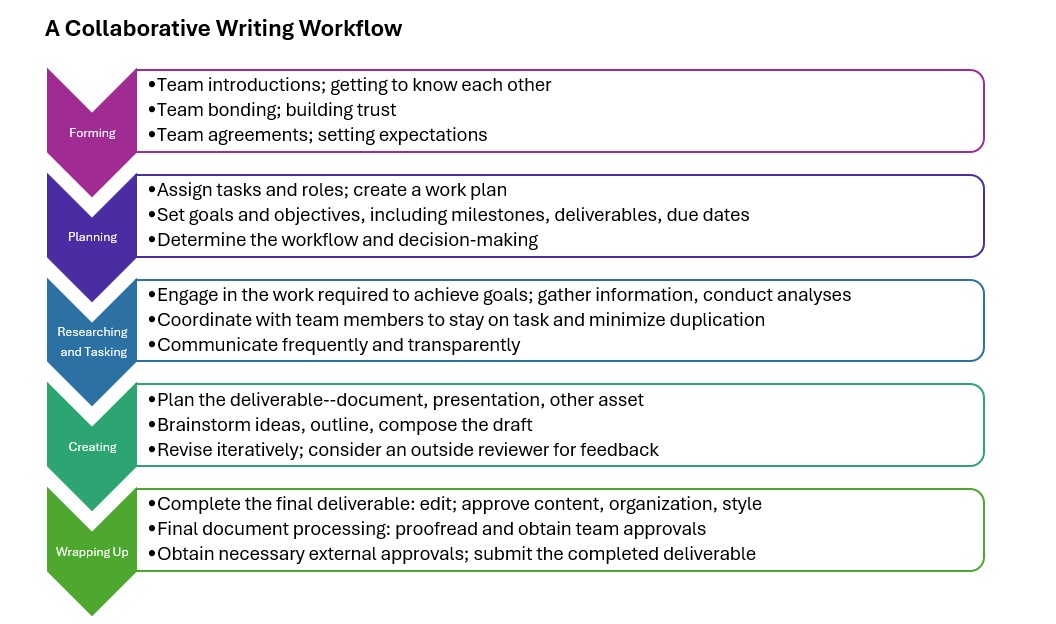

Successful collaborative writing is made easier when you understand the different strategies you can apply, how best to control the document, and the different roles people can assume. Figure 6.3.1 outlines the various activities involved at various stages of the collaborative writing process:

Integrating GenAI into the Collaborative Workflow

When integrating the use of a LLM into the work of a team, the team members must first carefully consider the workflow: what needs to be done, which tools would serve the team the best, and when to integrate the technology into the process. Completing an analysis of the workflow and identifying key tasks or roles it can perform and precisely at what point in the process will help the team plan for the integration of the LLM into the workflow. Remember that everyone shares responsibility for the work of the team, so well-considered and transparent use of AI technologies is essential to help establish and retain trust and confidence in the work being done by each team member.

Consider how a LLM can be integrated into the collaborative workflow to afford the team some assistance and efficiencies. With voice access and response along with camera access, the LLM can be seamlessly integrated into real-time interactions during an ongoing workflow. Here are suggested areas where a LLM could be found to be helpful:

Forming: In the forming stage, it’s all up to the team members. Developing interpersonal relationships has not as yet been supplanted by genAI, thankfully. However, it can be used to assist in formulating the team agreements: Asking the LLM, for example, to draft a set of team agreements based on criteria specified by the team can be a time-saving step.

Planning: As discussed in Chapter 6.1, planning the team workflow can be greatly facilitated with the assistance of a LLM. Given specific details and criteria, the LLM can be asked to draft the workplan including a task timeline, deliverables, and due dates.

Researching/Tasking: Using a two-lane approach to the research process is essential to the production of deliverables that align with organizational goals and reflect the team’s knowledge and expertise. A two-lane approach combines both human only and human-AI co-creation activities. If the team has analyzed the workflow and identified the strategic moments when integrating a LLM would offer the most benefit, the process will be efficient. Typically, team members would want to complete preliminary research without the use of a LLM so that they can gain important knowledge about the situation at hand. They would then also narrow the focus of the work and further research. At that point, using dedicated AI-assisted applications like Elicit and LLMs would expand and add depth to the research and help with problem and data analyses along with summarizing articles.

Creating: Once the research has been compiled, it makes the most sense for the team members to create the outline since they have the prior knowledge about the topic and have done the research. They can then ask a LLM to look over the outline for gaps and make suggestions for additional areas to be included. Once the outline has been drafted and research sources have been identified and situated in the outline, the team could then ask the LLM to draft the report in segments in a co-creative workflow. The draft would then be carefully reviewed by all team members. The review of the draft document of course would help to ensure accuracy, corroborate claims, and verify citations and other information. The team could also ask the LLM to review its own output for gaps. The same process could be followed for interim reporting, such as periodic or progress reports throughout the project, if it is an extended one.

Wrapping Up: After the draft has been edited, the LLM could then again be enlisted to review the edited version to provide suggestions on further improvements. The LLM could be asked to format citations and bibliographies. It can also be asked to format the document so that it is designed for readability, which would include headings and subheadings, along with listing for items in a series. A final check could be made to ensure the organization, tone, and style of writing is professional and suited to the context and audience. It the document is to be distributed across geographical boundaries, the LLM can be asked to edit for localization and even translate the text into other languages. If a project completion report is required, the team would outline the report including key information, and could ask the LLM to complete the draft that would then go through the same quality control process as the main deliverable.

The process is iterative, and the integration of the LLM is done in a discerning way, allowing the team to claim ownership over the deliverable and have confidence in its contents.

Collaborative Writing Strategies, Control, and Roles

Collaborative writing strategies are methods a team uses to coordinate the writing of a collaborative document. The five main strategies (see Table 6.3.1) each have their advantages and disadvantages. Can you think of any other benefits or limitations?

| [Skip Table] |

|||

| Writing Strategy |

When to Use | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-author

One member writes for the entire group. |

For simple tasks; when little buy-in is needed; for small groups. |

Efficient; consistent style. |

May not clearly represent the group’s intentions; less consensus produced |

| Sequential

Each member is in charge of writing a specific part and write in sequence. |

For asynchronous work with poor coordination; when it’s hard to meet often; for straightforward writing tasks; small groups. |

Easy to organize; simplifies planning. |

Can lose sense of group; subsequent writers may invalidate previous work; lack of consensus; version control issues |

| Parallel Writing: Horizontal Division

Members are in charge of writing a specific part but write in parallel. Segments are distributed randomly. |

When high volume of rapid output is needed; when software can support this strategy; for easily segmented, mildly complex writing tasks; for groups with good structure and coordination; small to large groups. |

Efficient; high volume of output. |

Redundant work can be produced; writers can be blind to each other’s work; stylistic differences; doesn’t recognize individual talents well. |

| Parallel Writing: Stratified Division

Members are in charge of writing a specific part but write in parallel. Segments are distributed based on talents or skills. |

For high volume rapid output; with supporting software; for complicated, difficult-to-segment tasks; when people have different talents/skills; for groups with good structure and coordination; small to large groups. |

Efficient; high volume of quality output; better use of individual talent. |

Redundant work can be produced; writers can be blind to each other’s work; stylistic differences; potential information overload. |

| Reactive Writing

Members create a document in real time, while others review, react, and adjust to each other’s changes and addition without much pre-planning or explicit coordination. |

Small groups; high levels of creativity; high levels of consensus on process and content. |

Can build creativity and consensus. |

Very hard to coordinate; version control issues. |

Document management reflects the approaches used to maintain version control of the document and describes who is responsible for it. Four main control modes are listed in Table 6.3.2, along with their pros and cons. Can you think of any others, based on your experience?

| Mode | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centralized | When one person controls the document throughout the process. | Can be useful for maintaining group focus and when working toward a strict deadline. | Non-controlling members may feel a lack of ownership or control of what goes into the document. |

| Relay | When one person at a time is in charge but the control changes in the group. | Democratic | Less efficient |

| Independent | When one person maintains control of his/her assigned portion. | Useful for remote teams working on distinct parts. | Often requires an editor to pull it together; can reflect a group that lacks agreement. |

| Shared | When everyone has simultaneous and equal privileges, such as when a document has shared electronic access. | Can be highly effective; helps to avoid redundancies; non-threatening; good for groups working remotely. | One person is the account holder where the document is stored. |

Roles refer to the different responsibilities participants might take on, depending on the activity. Table 6.3.3 describes several roles within a collaborative writing team. Which role(s) have you had in a group project? Are there ones you always seem to do? Ones that you prefer, dislike, or would like to try?

| Role | Description |

|---|---|

| Writer | A person who is responsible for writing a portion of the content |

| Consultant | A person who is external to the project and has no ownership or responsibility for producing content but who offers content and process-related feedback (peer reviewers outside the team; instructor) |

| Editor | A person who is responsible for the overall content production of the writers, and can make both style and content changes; typically has ownership of the content production |

| Reviewer | A person, internal or external, who provides specific content feedback but is not responsible for making changes |

| Team Leader | A person who is part of the team and may fully participate in authoring and reviewing the content, but who also leads the team through the processes, planning, rewarding, and motivating. |

| Facilitator | A person external to the team who leads the team through processes but doesn’t give content-related feedback. |

| AI-Assistant | An LLM that is enlisted by the team to assist at specific and agreed-upon moments during the document creation process. (Potter, 2024) |

Knowledge Check

Digital Collaboration Tools: A Sample List

Collaborative writing is made easier through the use of digital tools. Below is a shortlist of some Seneca-approved collaboration tools.

- Adobe Spark: Collaboratively create videos, infographics, slide decks, and more using the Adobe Spark suite of tools.

- Canva: Use Canva to collaboratively create, edit, and share infographics and other types of documents. Use free templates and images to create your own infographics, slide decks, and more.

- GenAI applications: Both LLMs and AI-enhanced collaboration platforms can be used to help teams get the job done. LLMs can serve as effective team members to help plan and delegate work, problem solve, and perform project-related tasks. AI-enhanced collaboration software like Teams, Google Workspace, and Slack, to name a few, allow project work shared and modified within one platform.

- Google Drive: Create collaboratively using Google Drive tools, which includes a suite of free document creation software, including Google Docs, Google Slides, Google Forms, which you can share with team members for real-time document creation and editing.

- Learn@Seneca: Use Blackboard Group tools to stay connected with your team. Using the Conversations features allow students to communicate with each other and stay on task.

- OneDrive: Store and share your documents using this cloud-based tool.

- Padlet: Brainstorm ideas with your team members using this bulletin-board-style tool.

- Wakelet: Curate and share your research materials, including links, videos, and images, with your team members using Wakelet.

- Zoom: Use Zoom to hold virtual meetings, share document links, display your work on screen, and conduct face-to-face or text chats.

The following video reviews a few online collaboration tools.

Exercise: Follow up and reflect

Refer back to the warm-up in Exercise 6.1.1 at the start of this section. Using the tables above, analyze your example to determine the writing strategy and mode that best describes your experience, and what role(s) you took on.

How effective was the strategy that you used? Would another strategy have been more effective?

References

BIT.AI. (2020). 21 Collaboration statistics that show the power of collaboration. https://blog.bit.ai/collaboration-statistics/

Educational Technology Advisory Committee. (n.d.). Educational technology tool finder. Seneca College Employee Pages.

GreggU. (2019) Using technolgy for collaboration in writing [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJlJCwmnV8M

Gimenez, J. & Thondhlana, J. (2012). Collaborative writing in engineering: Perspectives from research and implications for undergraduate education. European Journal of Engineering Education, 37(5), pp. 471-487. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2012.714356

Last, S. (2019). Technical writing essentials: Introduction to professional communications in the technical fields. OER. BCcampus. CC BY 4.0. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/

Lowry, P. B., Curtis, A., & Lowry, M. R. (2004). Building a taxonomy and nomenclature of collaborative writing to improve interdisciplinary research and practice. Journal of Business Communication, 41, pp. 66-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943603259363

McCahan, S., Anderson, P., Kortschot, M., Weiss, P. E., & Woodhouse, K. A. (2015). Introduction to teamwork. In Designing engineers: An introductory text. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, p. 14.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2012). The social economy: Unlocking value and productivity through social technologies. McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/the-social-economy

Swartz, J., Pigg, S., Larsen, J. Helo Gonzalez, J., De Haas, R. & Wagner, E. (2018). Communication in the workplace: What can NC State students expect? Report from the Professional Writing Program. North Carolina State University, 2018.