8.2 Integrating Evidence into Your Writing

Suzan Last; Candice Neveu; and Robin L. Potter

Writing in both academic and professional contexts often entails correctly and fluently incorporating and engaging with other writers’ words and ideas in your own writing. In business, whether you are writing a recommendation report or a brief, your credibility will ride on your ability to integrate other people’s ideas into your work seamlessly and ethically.

The three main ways to integrate evidence from sources into your writing include quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing. Each method requires a citation because you are using another person’s words and/or ideas. Even if you do not quote directly but paraphrase source content and express it in your own words, you still must give credit to the original authors for their ideas. Similarly, if you quote someone who says something that is “common knowledge,” you still must cite this quotation, as you are using their sentence structure, organizational logic, and/or syntax.

With the increasing use of LLMs in producing content, however, it’s important to understand the difference between what constitutes evidence and other forms of information, so you can determine what has enough value to be integrated as support for your arguments and statements. In addition, given that LLM output is used in various ways (as is, with some revisions, and with extensive revisions), having a good understanding of where the human cognitive load lies will help you determine the ways to integrate that content into your work. This chapter, then, describes the differences between evidence and output, discusses the human-AI co-creation gradient, and focuses largely on discussing how to integrate evidence into your documents.

Differentiating Evidence from LLM Output

When considering the use of AI output such as when discussing scientific, policy-related, organizational, or management matters, it is important to be clear about what constitutes evidence and what is output as they are fundamentally different. This difference helps to determine how you should treat the integration of this material into your work.

Evidence

Evidence consists of information and/or data that is verifiable and reliable and that is used to support claims, hypotheses, or other type of assertions (CEBMa, n.d.). Instead of relying on opinion or intuition, organizations must use evidence to guide their decision making. Evidence can be drawn from rigorous scientific studies or derived from “local organizational or business indicators like company metrics or observations of practice conditions” (CEBMa, n.d.). Sometimes, personal experience can be considered evidence. The key characteristic of evidence is that it is objective and verifiable in that researchers can confirm the information through repeated observations, experimentation, or data collection (CEBMa, n.d.).

If you are not completing original research by conducting observations, experiments, and statistical analyses, you can obtain important reporting on that type of research through reliable secondary sources, which do provide analyses and other types of information on original evidence.

Complex or extensive research requires that the evidence be synthesized (collected and combined) so that we can make sense and integrate it into the overall research objective. Cornell University Library (2025) describes the various ways in which research can be synthesized:

- Systematic Review: Using a methodical approach, systematic research focuses on a broad topic and results in the comparison, evaluation, and categorization of information. This time-consuming approach is used to discover the “effect of an intervention” (Cornell University Library, 2025).

- Literature (Narrative) Review: You may have seen literature reviews in the preambles of many published research papers. This type of comprehensive, synthesized research typically seeks to find out about previous studies on a topic to situate current work. General in scope, literature reviews can be conducted using various methodologies.

- Scoping Review or Evidence Map: The scoping and mapping process helps to gather and categorize information with the objective of identifying gaps in research and critically evaluating the work done on a topic.

- Rapid Review: The rapid review, as suggested by the name, consists of a systematic review that is completed within a specified and limited amount of time. This process is used when decisions are required in short order, but the process embodies a risk of bias due to the limited search.

- Umbrella Review: An umbrella search reviews other systematic reviews on a specified topic. This approach is used when you must sift through various intervention options.

- Meta-analysis: A meta-analysis consists of applying statistical analysis to “evaluate, synthesize, and summarize results” (Cornell University Library, 2025) obtained from various studies.

Many of these methods, such as the systematic review, the scoping review, and the umbrella review, can be time consuming, taking several months to a year or so to complete if done by humans alone. With the release of subscriber-only OpenAI Deep Research, the time can be significantly reduced to 30 minutes to an hour or so for all methods described above (Google Gemini’s Deep Research is not designed for this type of synthesis because it accesses internet materials only and not substantive research materials). OpenAI’s Deep Research is a research-dedicated tool that combines reasoning capabilities, LLM features, and agentic independence such that it is able to creatively and autonomously embark on diversified and focused research synthesis tasks. This application is reported to be effective in synthesizing large amounts of research information and producing reports that contain accurate quotes with few hallucinations (Mollick, 2025). While the applications can do the tedious work of gathering, analyzing, and categorizing information, the human user still is responsible for the accuracy, verification, and fair use of the information.

Deep research tools are not the same as LLMs, which are general purpose tools that do not have comparable research capabilities.

GenAI Output

GenAI output consists of content that is generated as a result of a prompt provided by a human. LLMs like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini enable multimodal content generation and are most used to generate text. LLM output is not research evidence nor does it provide reliable reporting on research results, so it is not recommended for use to support claims. Quoting LLM output does not boost your credibility in any way. Instead, use the output as a kind of gateway to further research.

LLMs function by using prediction and probability to generate content based on large data sets that contain copyrighted and uncopyrighted materials. They do not reproduce existing text, are not experts in any field, and are fallible. Therefore, they do not produce knowledge:

- LLMs do not complete original research through observation, experimentation, or methodical data collection, so they are not sources of primary research.

- Some LLMs are more biased than others and censorship is becoming more of a concern for models based both overseas and in the United States. In the United States, for example, current governmental limitations on the use of terms like “advocacy, biased, gender, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender), diversity, inclusion, marginalized, and underserved” (Anonymous, 2025) means that scientific research being reported by original researchers may not include important information affecting specific groups and areas of concern. That research will be reflected in the LLM output, so it too may integrate the censorship and bias, which may work against your best intentions. China’s Deep Seek, a research tool similar to the U.S.-based deep research tools, will not provide output about any topic that challenges the Chinese government’s official view of events.

- LLMs often produce content containing claims that are unsupported by verifiable sources.

- While Copilot output is increasingly accompanied by citations and references, beware of the following:

- LLM output does not contain quotations, so readers cannot know if the content is authentic or synthetic.

- LLM output may include citations, but often they do not match or align with the claims or statements in the output (see the example below).

- Some LLMs are better than others in providing verifiable sources, so depending on which one you use, the accuracy of the source information provided may be cause for concern.

- Many of the data sets upon which several LLMs were trained are current only to a certain year; output will not offer content beyond that year. Copilot, however, is connected to the internet, so it will produce citations that are current to what is available on the internet, but it does not access key scholarly databases like Semantic Scholar, so its output will be limited to articles that are available on the internet (and not behind paywalls).

- Often the output has an authoritative tone that signals that the content is correct when it may not be. As a result of this “linguistic persuasion,” the user can mistake the content as being an accurate and authentic form of knowledge when it is not (Stricker, 2025).

- Though the applications are improving, the output often contains hallucinations or fake information that would shatter the credibility of any researcher if the information were to be integrated into business documents.

In short, LLMs do not produce knowledge; they create synthetic knowledge (Stricker, 2025)–fake, inauthentic, unreviewed, and suspect content. While you can make use of the LLMs to support summarizing, drafting, and revising, it is ill advised to make use of general purpose LLM output as is for evidence in your business documents. Use of LLM output without carefully reviewing all content can result in significant financial, reputational, safety, individual, and organizational harm.

Check out the following example of a less than helpful Copilot output in which citations are included but lead to sources that are far from being considered evidence or even useful.

First, the example below does not offer citations relating to any peer-reviewed research. The sources that have been included are all culled from internet websites. So, while the internet does often offer helpful information, the information contained on many blog sites and internet articles is usually not cited.

Second, the example below clearly shows how Copilot provides citations that are not aligned with the topic areas or statements in the output. Here, many of the sources do pertain to women and sustainability, but they do not relate to the retail business in relation to women’s wear or the specific topic areas included in the listing. For example, consider the source provided for the Circular Fashion topic. The article does discuss how to integrate women into sustainability initiatives generally, but does not discuss their involvement in creating initiatives relating circular fashion.

Third, while the prompt asks for information specific to women’s wear, Copilot produces sources that feature women working in the sustainability arena, but they do not discuss sustainability in women’s wear in particular.

Example of Poor Copilot Reference Materials

Prompt: Copilot, (n.d.)

I’m working on a report on the topic of sustainability in the retail business, specifically when it comes to women’s wear. Please create a list of topics accompanied with verifiable research sources.

Output:

That sounds like an interesting and important report! Here are some key topics related to sustainability in the women’s wear retail business, along with verifiable research sources (table and article critique added):

| Topic and Source Generated by Copilot | Relevance of the Source Provided by Copilot |

Sustainable Materials and Fabrics:

|

The article aligns with the topic but does not mention materials and fabrics. |

Ethical Supply Chains:

|

The article does mention ethical sourcing, but not does not discuss the role of women in the process. |

Circular Fashion:

|

The article discusses various ways to integrate women in sustainability initiatives, but does not discuss circular fashion in any way and so is not aligned with the topic. |

Consumer Behavior and Demand:

|

The article profiles 5 women working in the sustainability space, but only one mentions sustainable fashion. |

Innovative Business Models:

|

The article is behind a subscription wall; only one of three women mentioned work in circular economies; no mention of direct-to-consumer brands in the preview. |

Regulatory and Compliance Issues:

|

The webpage focuses on the mission and vision of the organization Women in Sustainable Retail and does not discuss ESG regulations or compliance issues. |

Technological Innovations:

|

The article offers profiles of 10 women involved in ESG initiatives, but does not provide any discussion of blockchain for the supply chain industry. |

References

[1] Sustainable Business Practices: How Women Entrepreneurs Are Leading the …

[2] Sustainable Business Practices Led by Women – Hill Country Woman

[3] Women and Sustainability: Integrating Women Into Your Business … – BSR

[4] Celebrating women in sustainability: 5 women working … – Economist Impact

[5] The Future Is Female: Women Redefining Sustainability Leadership in 2025

[6] Home | Women in Sustainable Retail – WiSR

[7] Top 10: Women in ESG | Sustainability Magazine

[8] 20 Notable Women Who Led Corporate Sustainability in 2024

[9] Year in Review: Top 100 Women 2024 | Sustainability Magazine

All in all, Copilot in this instance does not prove to be effective in revealing any sources that offer substantial and meaningful discussion of the topics listed. So while the topic areas provided by Copilot offer some potential avenues of research, the sources provided offer little help and possibly more work than if you had gone straight to reliable databases for research. It may be tempting to use output as is, but as shown by this example it is a practice fraught with credibility perils. You will always be responsible for the work you integrate into your work, so be vigilant.

If you are working with such output then your options are as follows:

- Use detailed follow up prompts to direct the LLM to narrow the focus of its response to the area of research you are interested in learning more about and check all sources again.

- Use the Seneca Libraries research tools to access the databases for scholarly articles.

- Do your own web search using Google Scholar.

- Use Elicit to complete an AI-assisted search on Semantic Scholar.

Integrating LLM Output into Your Work

When integrating evidence from verifiable secondary sources like peer reviewed journals, websites, government documents, and the like, you would quote, summarize, or paraphrase the content and indicate origin by including an in-text citation.

LLM content, however, is being used by writers in a variety of ways:

- In whole and lightly edited (such as output created for correspondence)

- In part (such as when summarizing or paraphrasing original source materials)

- In whole or in part as human-AI co-created content

LLM output can also be integrated into your work but in a substantially revised form and following corroboration or checking of the output’s content. Given that LLMs have been pretrained on large data sets and produce text often with no clear provenance, tracing the statements to the original text can be challenging if not impossible. To be sure that the information is accurate, then, statements and claims must be corroborated or verified by finding original research material that you could confidently cite (while also acknowledging the output).

Differentiating between human-generated content and synthetic content and everything in between becomes essential when integrating both traditional sources and output into your work as their differences have implications for how they are integrated and understood.

Human-Generated Content vs Synthetic Content

How you integrate LLM output into your work will depend on where the cognitive load resides (see Chapter 2.6 Workflow and GenAI Co-Creation for more on the shifts in rhetorical or cognitive load). When completing rigorous secondary research, we have traditionally searched for documents that have been wholly created by humans and that have been peer reviewed. These kinds of documents are still the best kind to use for evidence because the content within often reports on original research or interprets it and is largely credible and verifiable because they have been reviewed prior to publication. With the release of LLMs and other genAI tools, however, and despite strong cautions, some people are now integrating into their documents content that has been created in whole or in part by machines that may have the appearance of evidence, but in fact is not such as discussed above. So what is the correct way to acknowledge the use of output? The answer is not easy to determine.

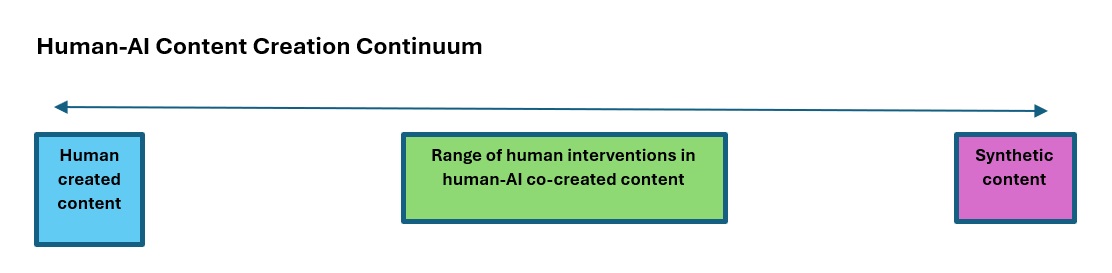

First, let’s consider the range of human involvement in the creation of content we typically integrate into our work. Drawing on the work of Alan Knowles (2024), we can conceptualize content creation along a continuum that looks like this:

Knowles explains that the degree to which AI is involved in content creation is a sign of how much of a shift in cognitive load has occurred. For example, when a text is wholly synthetic (AI-created), humans have had no involvement in the creation of that text; human cognitive load has been totally shifted to the machine. On the other hand, when a text is wholly human-created, AI has not been used in any way to create that text, humans retain the entire cognitive load or function in the creation of that text. Having the understanding that content can now be wholly created by humans, wholly created by AI, as well as co-created by humans and AI to varying degrees (depending on the degree of human revisions) will help us to understand the recommended practices for both integrating and citing content created in the Age of AI. The table below offers a tentative guide on integrating LLM output into your work.

Table 8.2.1 How to Integrate LLM Output into Your Work

| Degree of Output Use | Location of the Cognitive Load | Method of Integration into User Text | Citation or Declaration |

| Output is co-created through active human-AI engagement | Shared cognitive load in which the output contains considerable content provided by the user | Seamless integration using the user’s voice | Declare use |

| AI output is extensively revised | Human-leaning cognitive load | Seamless integration using the user’s voice | Declare use |

| AI output slightly revised | AI-leaning cognitive load | Signal AI use | Citation required |

| Used entirely as is or quoted in parts (not advised) | Cognitive load is fully shifted to AI | When quoted in parts

When used entirely as is |

Citation required |

Whichever method you use, it’s good practice to keep a record of your interactions with the LLM, including prompts and output versions. Some LLMs like Copilot/ChatGPT will allow you to keep a record of your prompting interactions on the application. For others, you would have to copy the prompts and output and keep them in a file on your computer. Should any questions arise about your use of LLM output, you can then refer to your record of interactions.

Integrating Quotations from Original Texts into Your Work

Using Direct Quotations

Direct quotations are comprised of brief amounts of text that are exact copies of the original. Quotes are typically used when you feel you cannot restate the idea in a better way than the original.

PURPOSE: Using direct quotations allows you to integrate someone else’s ideas into your argument using their own words. Quoting has several benefits:

- Integrating quotations provides direct evidence from reliable sources to support your argument.

- Using the words of verified sources conveys your credibility by showing you have done research into the area you are writing about and have consulted relevant and authoritative sources.

- Selecting effective quotations illustrates that you can extract the important aspects of information and use them effectively in your own argument.

Because LLMs are not recognized as human and statements contained in LLM output are always derived from training data and because claims made in the output always need verification for accuracy through verifiable external source materials, it is highly ill advised to quote LLM content. Always verify the output content, find verifiable sources, and substantially rewrite the output so that it is a co-created piece of content that you can then integrate into your document, followed by a declaration of AI use.

WHEN: When using direct quotations, be careful not to over-quote. Quotations should be used sparingly because too many quotations can interfere with the flow of ideas and make it seem like you don’t have ideas of your own. The same applies for LLM output. Typically, no more than a brief paragraph is quoted. Paraphrasing can be more effective in some cases.

So, when should you use quotations?

- If the language of the original source uses the best possible phrasing or imagery, and no paraphrase or summary could be as effective.

- If the use of language in the quotation is itself the focus of your analysis (e.g., if you are analyzing the author’s use of a particular image, metaphor, or other rhetorical strategies).

Knowledge Check

(Integrating Research into Your Paper, 2013)

How to Integrate Quotations Correctly

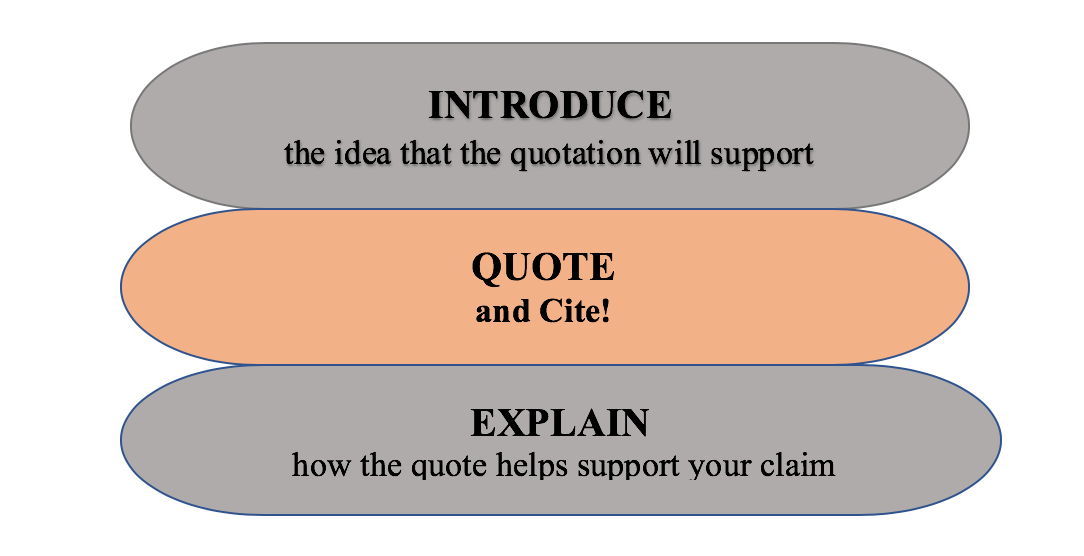

Integrating quotations into your writing happens on two levels: argumentative and grammatical. At the argument level, the quotation is being used to illustrate or support a point that you have made in your report, and you will follow it with some analysis, explanation, comment, or interpretation that ties that quote to your argument. Never quote and run: Don’t leave your reader to determine the relevance of the quotation. A quotation, statistic, or bit of data cannot speak for itself; you must provide context and an explanation for quotations you use. Essentially, you should create a “quotation sandwich” (see Figure 8.2.2). Remember the acronym I.C.E. → Introduce – Cite – Explain.

The second level of integration is grammatical. This involves integrating the quotation into your own sentences so that it flows smoothly and fits logically and syntactically. The three main methods to integrate quotations grammatically include the following:

- Seamless Integration Method: Embed the quoted words as if they were an organic part of your sentence (if you read the sentence aloud, your listeners would not know there was a quotation).

- Signal Phrase Method: Use a signal phrase (Author + Verb) to introduce the quotation, clearly indicating that the quotation comes from a specific source

- Colon Method: Introduce the quotation with a complete sentence ending in a colon.

Consider the following opening sentence (and famous comma splice) from A Tale of Two Cities (1859) by Charles Dickens, as an example:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. . .”

1. Seamless Integration: Embed the quotation, or excerpts from the quotation, as a seamless part of your sentence:

Charles Dickens begins his novel with the paradoxical observation that the eighteenth century was both “the best of times” and “the worst of times” (Dickens, 1859).

2. Signal Phrase: Introduce the author and then the quote using a signal verb (scroll down to see a list of common verbs that signal you are about to quote someone):

Describing the eighteenth century, Charles Dickens observes, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” (Dickens, 1859).

3. Colon: If you use your own introductory words form a complete sentence, you can use a colon to introduce and set off the quotation. This can give the quotation added emphasis.

Dickens defines the eighteenth century as a time of paradox: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” (Dickens, 1859).

The eighteenth century was a time of paradox: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” (Dickens, 1859).

Reference:

Dickens, C. (1859). A tale of two cities. Serialized. Discovering Dickens: A Community Reading Project. Stanford University. https://dickens.stanford.edu/dickens/archive/tale/cities_issue1.html

Knowledge Check

Editing Quotations

When you use quotation marks around the material, this indicates that you have used the exact words of the original author. See the example below.

“Corporate Social Responsibility, or ‘CSR,’ refers to the need for businesses to be good corporate citizens. CSR involves going beyond the law’s requirements in protecting the environment and contributing to social welfare. It is widely accepted as an obligation of modern business” (McCombs School of Business, 2022).

McCombs School of Business. (2022). Ethics Unwrapped: Corporate Social Responsibility. The University of Texas at Austin. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary/corporate-social-responsibility

Sometimes the text you want to quote will not fit grammatically or clearly into your sentence without making some changes. Perhaps you need to replace a pronoun in the quote with the actual noun to make the context clear, or perhaps the verb tense does not fit. Two key ways to edit a quotation to make it fit grammatically with your own sentence are as follows:

- Use square brackets: To reflect changes or additions to a quote, place square brackets around any words that have been changed or added.

- Use ellipses (3 dots): To show that some text has been removed, use the ellipses. Three dots indicate that some words have been removed from the sentence; four dots indicate that a substantial amount of text has been deleted, including the period at the end of a sentence.

You are allowed to change the original words, to shorten the quoted material or integrate material grammatically, but only if you signal those changes appropriately with square brackets or ellipses:

Example 1: The authors observed that “[s]ome people contend that companies owe no duty to society outside making as much money as possible within the law” (McCombs School of Business, 2022).

Example 2: “CSR goes beyond earning money for shareholders. It’s concerned with protecting the interests of all stakeholders. . . Examples of CSR include adopting humane employee practices, caring for the environment, and engaging in philanthropic endeavours (McCombs School of Business, 2022).

Integrating Lengthy Quotations

When making use of any segment of text that extends beyond four lines, the quoted material is formatted by indentation. In this case the indentation signals that the text is quoted. Add a citation at the end.

Use of an Extended Quotation

Your paragraph would precede the quotation such as this sentence, then the quotation would be integrated in an indented format as follows:

Corporate Social Responsibility, or ‘CSR,’ refers to the need for businesses to be good corporate citizens. CSR involves going beyond the law’s requirements in protecting the environment and contributing to social welfare. It is widely accepted as an obligation of modern business.

CSR goes beyond earning money for shareholders. It’s concerned with protecting the interests of all stakeholders, such as employees, customers, suppliers, and the communities in which businesses operate. Examples of CSR include adopting humane employee practices, caring for the environment, and engaging in philanthropic endeavours.

Some people contend that companies owe no duty to society outside making as much money as possible within the law. But those who support Corporate Social Responsibility believe that companies should pursue a deeper purpose beyond simply maximizing profits. (McCombs School of Business, 2022)

Integrating Paraphrases and Summaries

Instead of using direct quotations, you can paraphrase and summarize evidence to integrate it into your argument more succinctly. Both paraphrase and summary requires you to read the source carefully, understand it, and then rewrite the idea in your own words. Using these forms of integration demonstrates your understanding of the source, because rephrasing requires a good grasp of the core ideas.

(Comparing Paraphrasing and Quoting, 2020)

Paraphrase and summary differ in that a paraphrase focuses on a smaller, specific section of text that when paraphrased may be close to the length of the original. Summaries, on the other hand, are condensations of large chunks of text, so they are much shorter (about 1/3 of the original length) than the original and capture only the main ideas. For more information on how to write a summary, see Chapter 8.1: Writing Summaries.

Regardless of whether you are quoting, paraphrasing or summarizing, you must cite your source any time you use someone else’s intellectual property—whether in the form of words, ideas, language structures, images, statistics, data, or formulas—in your document. When using LLM output as described in Table 8.2.1, you can either cite or declare your use of it.

(Paraphrasing Process Demonstrated, 2020)

Using Signal Verbs

Use signal verbs to introduce summaries and paraphrased content. Verbs like “says,” “writes,” or “discusses” tend to be commonly over-used to signal a quotation and are rather vague. In very informal situations, people use “talks about” (avoid “talks about”). All these verbs do not provide much information about the rhetorical purpose of the author.

The list of signal verbs below offers suggestions for introducing quoted, paraphrased, and summarized material that convey more information than verbs like “says” or “writes” or “discusses.” When choosing a signal verb, try to indicate the author’s rhetorical purpose: What is the author doing in the quoted passage? Is the author describing something? Explaining something? Arguing? Giving examples? Estimating? Recommending? Warning? Urging? Be sure the verb you choose accurately represents the intention of the source text. For example, don’t use “concedes” if the writer isn’t actually conceding a point. Look up any words you don’t know and add ones that you like to use.

Table 8.2.2 Commonly used signal verbs (Last, 2019)

| Making a claim | Recommending | Disagreeing or Questioning | Showing | Expressing Agreement | Additional Signal Verbs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| argue

assert believe claim emphasize insist remind suggest hypothesize maintains |

advocate

call for demand encourage exhort implore plead recommend urge warn |

challenge

complicate criticize qualify counter contradict refute reject deny question |

illustrates

conveys reveals demonstrates proposes points out exemplifies indicates |

agree

admire endorse support affirm corroborate verify reaffirm |

responds

assumes speculates debates estimates explains implies uses |

Be careful with the phrasing after your signal verb. In some cases, you will use “that” to join the signal phrase to the summarized or paraphrased text:

Smith argues that bottled water should not be allowed on college campuses (Smith, 20XX).

But not all signal verbs can be followed by “that.”

It would be incorrect to write the following:

-

-

- The author persuades that …x

- The writers convince that … x

- The speaker expressed that …x

- He analyzes that …x

- She informs that … x

- They described that …x

- I support that … x

-

We can use clauses with that after these verbs related to thinking:

Think I think that you have an excellent point.

Believe He believes that unicorns exist.

Expect She expects that things will get better.

Decide He decided that it would be best to buy the red car.

Hope I hope that you know what you are doing.

Know I know that you will listen carefully

Understand She understood that this would be complicated.

And after verbs related to saying:

Say She said that she would be here by 6 pm.

Admit He admits that the study had limitations.

Argue She argues that bottled water should be banned on campus.

Agree He agrees that carbon taxes are effective.

Claim They claim that their methods are valid.

Explain He explained that the rules are complicated.

Suggest They suggest that you follow instructions carefully.

But some verbs require an object (a person or thing) before you can use “that”:

Tell tell a person that… tell as story… tell the truth

Describe describe the mechanism

Convince convince an audience that you are credible

Persuade persuade a reader that this is a worthwhile idea

Inform inform a colleague that their proposal has been accepted

Remind remind the client that …

Analyze analyze a process; analyze a text; analyze the problem

Summarize summarize a text; summarize an idea

Support I support the idea that all people are created equal

Exercise: Integrating Quotations

References

Last, S. (2019) Technical writing essentials. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/

McCombs School of Business. (2022). Ethics Unwrapped: Corporate Social Responsibility. The University of Texas at Austin. https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary/corporate-social-responsibility

Seneca Libraries. (2013). Integrating research into your paper [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LVew23RFBSk

Stricker, J. K. (2025, February 5). The Synthetic Knowledge Crisis. The Future of Higher Education Blog. Substack.

WUWritingCenter. (2020). Comparing paraphrasing and quoting [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_mMSReRhqqw&t=15s

WUWritingCenter. (2020). Paraphrasing process demonstrated [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZJXWaOWqT0