5.5 Intercultural Communication

Intercultural communication is communication between people with differing cultural identities. Culture and identity are created, understood, and transformed through intercultural communication. Given the almost “border-less” nature of business, it is essential to become adept at communicating effectively and respectfully with others from different cultures. Another reason you should study intercultural communication is to foster greater self-awareness (Martin & Nakayama, 2010).

Defining Culture

Culture is the term used to describe this dimension of meaningful collective existence. Culture refers to the shared symbols that people create to solve real-life problems. Human social life is necessarily conducted through the meanings humans attribute to things, actions, others, and themselves. In a sense, people do not live in direct, immediate contact with the world and each other; instead, they live only indirectly through the medium of the shared meanings provided by culture. This mediated experience is the experience of culture.

Culture can be defined as patterns of learned and shared behavior that are cumulative and transmitted across generations. We see patterns in the systematic and predictable ways of behavior or thinking across members of a culture. Patterns reflect how people think and feel, as well as what they believe. These patterns emerge from adapting, sharing, and storing cultural information. Patterns can be both similar and different across cultures. For example, in both Canada and India it is considered polite to bring a small gift to a host’s home. In Canada, it is more common to bring a bottle of wine and for the gift to be opened right away. In India, by contrast, it is more common to bring sweets, and often the gift is set aside to be opened later.

Culture is the product of people sharing with one another. Humans cooperate and share knowledge and skills with other members of their networks. The ways they share, and the content of what they share, helps make up culture. Older adults, for instance, remember a time when long-distance friendships were maintained through letters that arrived in the mail every few months. Contemporary youth culture accomplishes the same goal through the use of instant text messages on smartphones.

Behaviors, values, norms are acquired through a process known as enculturation that begins with parents and caregivers because they are the primary influence on young children. Caregivers teach kids, both directly and by example, about how to behave and how the world works. They encourage children to be polite, reminding them, for instance, to say “Thank you.” They teach kids how to dress in a way that is appropriate for the culture.

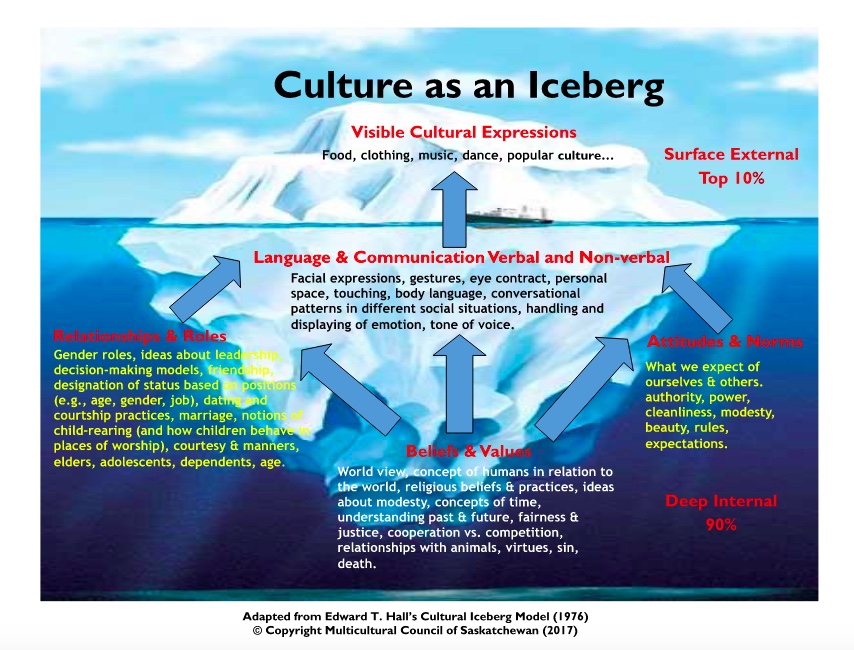

Culture can be easily mistaken for the superficial signs that offer some indications of cultural expression. However, culture is much deeper than the eye can see, as shown in the culture iceberg of Figure 5.5.1, which is an adaptation of Edward Hall’s original version and which is commonly used to help visualize the hidden depths of culture.

Many misunderstandings can be avoided by remembering that in whatever context you find yourself, factors that may not be readily evident may be at play in your interactions with others. Using this empathetic understanding will allow you to seek a deeper understanding while developing a mindful approach or response. Ethnocentrism, however, may make you far less likely to be able to bridge the gap with others and often increases intolerance of difference. Business and industry are no longer regional, and in your career, you will necessarily cross borders, languages, and cultures. A skilled business communicator knows that the best approach is derived from an accepting, understanding, patient, and open mindset.

Knowledge Check

Clarifying Terms

Although they are often used interchangeably, it is important to note the distinctions between the terms referring to culture.

First, communication with yourself is called intrapersonal communication, which may also be intracultural, as you may only represent one culture. But most people belong to multiple groups, each with their own culture. For example, consider a person who resides in Ontario and visits Quebec on business. She begins to communicate verbally in French. She may then often find herself thinking and speaking to herself not in English but in French if she is fluent in that language. Surely the language in this case brings back lived experience and informs how thinking occurs and which expressions are used that reflect the culture around. Sometimes a conversation with yourself reveals competing goals, objectives, needs, wants, or values. How did you learn of those goals, or values? Similarly, you may struggle with the demands of various groups and their expectations and could consider this struggle intercultural conflict.

Multiculturalism refers to both the existence of a diversity of cultures within one territory and to a way of conceptualizing and managing cultural diversity. As a policy, multiculturalism seeks to both promote and recognize cultural differences while addressing the inevitability of cultural tensions. Critics of multiculturalism identify four related problems:

- Multiculturalism only superficially accepts the equality of all cultures; e.g., there are only two official languages in Canada.

- Multiculturalism obliges minority individuals to assume the limited cultural identities of their ethnic group of origin, which leads to stereotyping.

- The ideal of multiculturalism isolates groups who do not integrate into existing Canadian society.

- Multiculturalism is based on recognizing group rights which undermines constitutional protections of individual rights.

According to Olds College, “Cross-cultural approaches typically go a bit deeper, the goal being to be more diplomatic or sensitive. They account for some interaction and recognition of difference through trade and cooperation, which builds some limited understanding—such as, for instance, bowing instead of shaking hands, or giving small but meaningful gifts. . . . Sadly, they are not always nuanced comparisons; a common drawback of cross-cultural comparisons is that we can wade into stereotyping and ethnocentric attitudes—judging other cultures by our own cultural standards—if we aren’t mindful” (2020).

Intercultural societies, on the other hand, show deep comprehension and respect for differences. Members of an intercultural society learn and grow from one another. Interactions within the society are based not on tolerance but on acceptance and lead to the mutual exchange of ideas and norms to build deeper relationships. For businesses to succeed in the global economy, intercultural relationships must be developed for sustained growth and cooperation. This can be achieved through mindful intercultural communication, which will be discussed below.

Understanding Intercultural Communication

The American anthropologist Edward T. Hall is often cited as a pioneer in the field of intercultural communication (Leeds-Hurwitz, 1990; Chen & Starosta, 2000). Born in 1914, Hall spent much of his early adulthood in the multicultural setting of the American Southwest, where Native Americans, Spanish-speakers, and descendants of pioneers came together from diverse cultural perspectives. He then traveled the globe during World War II and later served as a U.S. State Department official. Whereas culture had once been viewed by anthropologists as a single, distinct way of living, Hall saw how individual perspective influences interaction.

By focusing on interactions rather than cultures as separate from individuals, he asked people to evaluate the many cultures they belong to or are influenced by, as well as those with whom they interacted. While his view makes the study of intercultural communication far more complex, it also brings a healthy dose of reality to the discussion. Hall is generally credited with eight contributions to the study of intercultural communication as follows:

- Focus on the interactions: Avoid focusing on the generalities of culture; rather, focus on the interactions versus general observations.

- Shift to a local perspective: A global perspective greatly widens the context within which interactions occur. Shift to a local perspective rather than focusing on a global perspective to make the analysis of interactions understandable and manageable.

- Strive to understand local signs: Time, space, gestures, and gender roles can be studied, even if we lack a larger understanding of the entire culture.

- Learn the rules: People create rules for themselves in each community that we can learn from, compare, and contrast.

- Honor personal experience: Personal experience has value in addition to more comprehensive studies of interaction and culture.

- Use linguistics as a model: Descriptive linguistics serves as a model to understand cultures, and the U.S. Foreign Service adopted it as a basis for training

- Apply understanding to trade and commerce: Intercultural communication can be applied to international business. U.S. Foreign Service training yielded applications for trade and commerce and became a point of study for business majors

- Recognize the interconnectivity of culture and communication: Culture and communication are intertwined and bring together many academic disciplines.

(Chen & Starosta, 2000; Leeds-Hurwitz, 1990; McLean, 2005).

Hall indicated that emphasis on a culture as a whole, and how it operated, might lead people to neglect individual differences. Individuals may hold beliefs or practice customs that do not follow their own cultural norm. When you resort to the mental shortcut of a stereotype, you lose these unique differences. Stereotypes can be defined as a generalization about a group of people that oversimplifies their culture (Rogers & Steinfatt, 1999). Similarly, the American psychologist Gordon Allport explored how, when, and why people formulate or use stereotypes to characterize distinct groups. When you do not have enough contact with people or their cultures to understand them well, you tend to resort to stereotypes (Allport, 1958).

In addition, prejudice involves a negative preconceived judgment or opinion that guides conduct or social behaviour (McLean., 2005). As an example, imagine two people walking into a room for a job interview. You are tasked to interview both. Will the candidates’ dress, age, or gender influence your opinion of them? Will their race or ethnicity be a conscious or subconscious factor in your thinking process? Allport’s (1958) work would indicate that those factors and more will make you likely to use stereotypes to guide your expectations of them and your subsequent interactions with them. Sometimes prejudices also assume similarity, thinking that people are all basically similar. This denies cultural, racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and many other valuable, insightful differences. In summary, ethnocentric tendencies, stereotyping, and assumptions of similarity can make it difficult to learn about cultural uniqueness and build understanding.

Knowledge Check

Exploring Cultural Characteristics: The Business Context

Figure 5.5.2 Culture Characteristics

Groups come together, form cultures, and grow apart across time. How do you become a member of a community, and how do you know when you are full member? What aspects of culture do people have in common, and how do they relate to business communication? Researchers who have studied cultures around the world have identified certain characteristics that define a culture. These characteristics are expressed in different ways, but they tend to be present in nearly all cultures.

Initiations

Across the course of your life, you have undoubtedly passed several rites of initiation but may not have taken notice of them. Did you earn a driver’s license, register to vote, or acquire the permission to purchase alcohol? In North American culture, these three common markers indicate the passing from a previous stage of life to a new one, with new rights and responsibilities.

Cultures tend to have rituals for becoming a new member. A newcomer starts out as an unaffiliated person with no connection or even possibly awareness of the community. Newcomers who stay around and learn about the culture become members. Most cultures have a rite of initiation that marks the passage of the individual into the community; some of these rituals may be so informal as to be hardly noticed (e.g., the first time a coworker asks you to join the group to eat lunch together), while others may be highly formalized (e.g., the ordination of clergy into religious service). The unaffiliated person becomes a member, the new member becomes a full member, and individuals rise in terms of responsibility and influence.

Rites of initiation mark the transition of the role or status of the individual within the group. Your first day on the job may have been a challenge as you learned your way around the physical space, but the true challenge was to learn how the group members in your department communicate with each other. In every business, there are groups, power struggles, and unspoken ways that members earn their way from the role of a “newbie” to that of a full member. The newbie may get the tough account, the office without a window, or the cubicle next to the photocopier, denoting low status. As new members learn to navigate through the community—establishing their reputation and being promoted—they pass the rite of initiation and acquire new rights and responsibilities.

Over time, the person comes to be an important part of the business, a “keeper of the flame.” The “flame” may not exist in physical space or time, but it does exist in the minds of those members in the community who have invested time and effort in the business. It is not a flame to be trusted to a new person, as it can only be transferred as the person develops trust with the group. Along the way, there may be personality conflicts and power struggles over resources and perceived scarcity (e.g., there is only one promotion and everyone wants it). All these challenges are to be expected in any culture.

Shared History and Traditions

Cultures celebrate heroes, denigrate villains, and have specific ways of completing jobs and tasks. In business and industry, the emphasis may be on effectiveness and efficiency, but the practice can often be “because that is the way we have always done it.” Traditions serve to guide our performance and behaviour and may be limited to small groups or celebrated across the entire company.

Think for a moment about the history of a business like Tim Hortons—what are your associations with Tim Horton; what are the relationships between hockey, coffee, and donuts? Traditions form as the organization grows and expands, and stories are told and retold to educate new members on how business should be conducted. The history of every culture, of every corporation, influences the present to the point that the phrase “we’ve tried that before” can become a stumbling block for members of the organization, for example, as it grows and adapts to new market forces.

Traditions can serve to bind a group together or to constrain it. Institutions tend to formalize processes and then have a hard time adapting to new circumstances. While the core values or mission statement may hold true, the method of doing things that worked in the past may not be as successful as it once was. Adaptation and change can be difficult for individuals and companies, and yet all communities, cultures, and communication contexts are dynamic, or always changing. As much as we might like things to stay the same, they will always change—and we will change with (and be changed by) them.

Shared Values and Principles

Cultures all hold values and principles that are commonly shared and communicated from older members to younger (or newer) ones. In organizations, these are often communicated through action, attitude, and goals, and new employees learn of these through those around them. Established organizations may explicitly describe the values and principles; however, often they are not so clearly evident and are learned with time and experience.

Shared Purpose and Mission

Cultures share a common sense of purpose and mission. Why are we here and whom do we serve? In business, the answers to these questions often can be found in mission and vision statements of almost every organization. Individual members will be expected to acknowledge and share the mission and vision and make them real through action. Without action, the mission and vision statements are simply an arrangement of words. As a guide to individual and group behavioural norms, they can serve as a powerful motivator and a call to action. For example, Boeing Canada’s Purpose and Mission, and Aspiration statements are as follows:

Purpose and Mission: Connect, Protect, Explore and Inspire the World through Aerospace Innovation

Aspiration: Best in Aerospace and Enduring Global Industrial Champion

Based on these two statements, employees might expect a culture of innovation, quality, and safety as core to their work. What might those concepts mean in your everyday work if you were part of Boeing “culture?”

Employees at the administrative level and those who aspire to leadership roles would also find mission and values explained more fully in the organization’s strategic plans, which often set out key goals for a specific period, say 2-5 years. These plans are important documents that serve to guide administrators in designing their departmental-level goals and projects such that they align with the overall purpose and goals of the organization as a whole.

Shared Symbols, Boundaries, Status, and Language

Many people learn early in life what a stop sign represents, but not everyone knows what a ten-year service pin on a lapel, or a corner office with two windows means. Cultures have common symbols that mark them as a group; the knowledge of what a symbol stands for helps to reinforce who is a group member and who is not. Cultural symbols include dress, such as the Western business suit and tie in North America. Symbols also include slogans or sayings, such as “Mr. Christie you make good cookies” or “Noooobody”. The slogan may serve a marketing purpose but may also embrace a mission or purpose within the culture. Family crests and clan tartan patterns serve as symbols of affiliation. Symbols can also be used to communicate rank and status within a group.

Space and status are other common cultural characteristics; space may be a nonverbal symbol that represents status and power. In most of the world’s cultures, a person occupying superior status is entitled to a physically elevated position. In business, the corner office may offer the best view with the most space. Movement from a cubicle to a private office may also be a symbol of transition within an organization, involving increased responsibility as well as power. Parking spaces, the kind of vehicle you drive, and the transportation allowance you have may also serve to communicate symbolic meaning within an organization.

In some organizations, however, this notion of status is resisted. Think, for example, of how Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook has insisted on working in the same open plan office space as his other employees, thus signaling a wish to be fully involved as any other employee in the day to day operations of the organization. Regardless, whatever the context, boundaries are important to consider. Would you sit on your boss’s desk or in his chair with your feet up on the desk in his presence? Most people indicate they would not, because doing so would communicate a lack of respect, violate normative space expectations, and invite retaliation.

Communities have their own vocabulary and way in which they communicate. Consider the person who uses a sewing machine to create a dress and the accountant behind the desk who uses software to create a spreadsheet; both are professionals and both have specialized jargon used in their field. If they were to change places, the lack of skills would present an obstacle, but the lack of understanding of terms, how they are used, and what they mean would also severely limit their effectiveness. Those terms and how they are used are learned over time and through interaction. While a textbook can help, it cannot demonstrate use in live interactions.

Read the following web article: Culture at Work: The Tyranny of ‘Unwritten Rules’

Knowledge Check

Understanding Divergent Cultural Characteristics

People have viewpoints, and they are shaped by their interactions with communities. Cultures reflect inequality, diversity, and the divergent range of values, symbols, and meanings across communities. Let’s examine several points of divergence across cultures.

Figure 5.5.3 Image of teamwork (Pixabay.com)

Individualistic versus Collectivist Cultures

The Dutch researcher Geert Hofstede explored the concepts of individualism and collectivism across diverse cultures (Hofstede, 2005). He found that in individualistic cultures like the United States and Canada, people value individual freedom and personal independence, and perceive their world primarily from their own viewpoint. They perceive themselves as empowered individuals, capable of making their own decisions, and able to make an impact on their own lives.

Cultural viewpoint is not an either/or dichotomy, but rather a continuum or range. You may belong to some communities that express individualistic cultural values, while others place the focus on a collective viewpoint. Collectivist cultures (Hofstede, 1982), including many in Asia and South America, and many Indigenous cultures, focus on the needs of the nation, community, family, or group of workers. Ownership and private property is one way to examine this difference. In some cultures, property is almost exclusively private, while others tend toward community ownership. The collectively owned resource returns benefits to the community. Water, for example, has long been viewed as a community resource, much like air, but that has been changing as business and organizations have purchased water rights and gained control over resources. How does someone raised in a culture that emphasizes the community interact with someone raised in a primarily individualistic culture? How could tensions be expressed and how might interactions be influenced by this point of divergence?

Trompenaar’s research (1998) suggested cultures may change more quickly than we realize and showed Mexico and the former communist countries of Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union have high levels of individualism. Mexico’s involvement in NAFTA and the global economy could explain the shift from a communitarian culture. This contrasts with Hofstede’s earlier research, which found these countries to be collectivist and shows the dynamic and complex nature of culture. Countries with high communitarianism include Germany, China, France, Japan, and Singapore.

Explicit-Rule Cultures versus Implicit-Rule Cultures

Do you know the rules of your business or organization? Did you learn them from an employee manual or by observing the conduct of others? Your response may include both options, but not all cultures communicate rules in the same way. In an explicit-rule culture, where rules are clearly communicated so that everyone is aware of them, the guidelines and agenda for a meeting are announced prior to the gathering. In an implicit-rule culture, where rules are often understood and communicated non-verbally, there may be no agenda. Everyone knows why they are gathered and what role each member plays, even though the expectations may not be clearly stated. Power, status, and behavioural expectations may all be understood, and to the person from outside this culture, it may prove a challenge to understand the rules of the context.

“Outsiders” often communicate their “otherness” by not knowing where to stand, when to sit, or how to initiate a conversation if the rules are not clearly stated. While it may help to know that implicit-rule cultures are often more tolerant of deviation from the understood rules, the newcomer will be wise to learn by observing quietly—and to do as much research ahead of the event as possible.

High context and low context cultures

High context cultures are replete with implied meanings beyond the words on the surface and even body language that may not be obvious to people unfamiliar with the context. Low context cultures are typically more direct and tend to use words to attempt to convey precise meaning.

For example, an agreement in a high context culture might be verbal because the parties know each other’s families, histories, and social position. This knowledge is sufficient for the agreement to be enforced because the shared understanding is implied and highly contextual. A low context culture usually requires highly detailed, written agreements that are signed by both parties, sometimes mediated through specialists like lawyers, as a way to enforce the agreement. This is low context because the written agreement spells out all the details so that not much is left to the imagination or “context.”

Watch the video below for an illustration of how communication can be altered when two different cultures communicate.

Uncertainty-Accepting Cultures versus Uncertainty-Rejecting Cultures

When people meet each other for the first time, they often use what they have previously learned to understand their current context. People also do this to reduce uncertainty. Some cultures, such as the United States and Britain, are highly tolerant of uncertainty, while others go to great lengths to reduce the element of surprise. Whereas a U.S. business negotiator might enthusiastically agree to try a new procedure, the Egyptian counterpart would likely refuse to get involved until all the details are worked out.

Charles Berger and Richard Calabrese (1975) developed the Uncertainty Reduction theory to examine this dynamic aspect of communication. Here are seven axioms of uncertainty:

1. There is a high level of uncertainty at first. As we get to know one another, our verbal communication increases and our uncertainty begins to decrease.

2. Following verbal communication, nonverbal communication increases, uncertainty continues to decrease, and more nonverbal displays of affiliation, like nodding one’s head to indicate agreement, will start to be expressed.

3. When experiencing high levels of uncertainty, we tend to increase our information-seeking behaviour, perhaps asking questions to gain more insight. As our understanding increases, uncertainty decreases, as does the information-seeking behaviour.

4. When experiencing high levels of uncertainty, the communication interaction is not as personal or intimate. As uncertainty is reduced, intimacy increases.

5. When experiencing high levels of uncertainty, communication will feature more reciprocity, or displays of respect. As uncertainty decreases, reciprocity may diminish.

6. Differences between people increase uncertainty, while similarities decrease it.

7. Higher levels of uncertainty are associated with a decrease in the indication of liking the other person, while reductions in uncertainty are associated with liking the other person more.

Time Orientation

Edward T. Hall and Mildred Reed Hall (1987) state that monochronic cultures consider one thing at a time, whereas polychronic cultures schedule many things at one time, and time is considered in a more fluid sense. In monochromatic time, interruptions are to be avoided, and everything has its own specific time. Even the multi-tasker from a monochromatic culture will, for example, recognize the value of work first before play or personal time. Canada, Germany, and Switzerland are often noted as countries that value a monochromatic time orientation.

Polychromatic time looks a little more complicated, with business and family mixing with dinner and dancing. Greece, Italy, Chile, and Saudi Arabia are countries where one can observe this perception of time; business meetings may be scheduled at a fixed time, but when they actually begin may be another story. Also note that the dinner invitation for 8 p.m. may in reality be more like 9 p.m. If you were to show up on time, you might be the first person to arrive and find that the hosts are not quite ready to receive you.

When in doubt, always ask before the event; many people from polychromatic cultures will be used to foreigner’s tendency to be punctual, even compulsive, about respecting established times for events. The skilled business communicator is aware of this difference and takes steps to anticipate it. The value of time in different cultures is expressed in many ways, and your understanding can help you communicate and do business more effectively.

Short-Term versus Long-Term Orientation

Figure 5.5.4 Short-Term/Long-Term. (ecampusontario)

Do you want your reward right now or can you dedicate yourself to a long-term goal? You may work in a culture whose people value immediate results and grow impatient when those results do not materialize. Geert Hofstede (2001) discusses this relationship of time orientation to a culture as a “time horizon,” and it underscores the perspective of the individual within a cultural context. Many countries in Asia, influenced by the teachings of Confucius, value a long-term orientation, whereas other countries, including Canada, have a more short-term approach to life and results. Indigenous peoples are known for holding a long-term orientation driven by values of deep, long-term reflection and community consultation.

If you work within a culture that has a short-term orientation, you may need to place greater emphasis on reciprocation of greetings, gifts, and rewards. For example, if you send a thank-you note the morning after being treated to a business dinner, your host will appreciate your promptness. While there may be a respect for tradition, there is also an emphasis on personal representation and honour, a reflection of identity and integrity. Personal stability and consistency are also valued in a short-term oriented culture, contributing to an overall sense of predictability and familiarity.

Long-term orientation is often marked by persistence, thrift and frugality, and an order to relationships based on age and status. A sense of shame for the family and community is also observed across generations. What an individual does reflects on the family and is carried by immediate and extended family members.

Direct versus Indirect

In Canada, business correspondence is expected to be short and to the point. “What can I do for you?” is a common question when a business person receives a call from a stranger; it is an accepted way of asking the caller to state his or her business. In some cultures it is quite appropriate to make direct personal observation, such as “You’ve changed your hairstyle,” while for others it may be observed, but never spoken of in polite company. In indirect cultures, such as those in Latin America, business conversations may start with discussions of the weather, or family, or topics other than business as the partners gain a sense of each other, long before the topic of business is raised. Again, the skilled business communicator researches the new environment before entering it, as a social faux pas, or error, can have a significant impact.

Materialism versus Relationships

Members of a materialistic culture place emphasis on external goods and services as a representation of self, power, and social rank. If you consider the plate of food before you, and consider the labour required to harvest the grain, butcher the animal, and cook the meal, you are focusing more on the relationships involved with its production than the foods themselves. Caviar may be a luxury, and it may communicate your ability to acquire and offer a delicacy, but it also represents an effort. Cultures differ in how they view material objects and their relationship to them, and some value people and relationships more than the objects themselves.

Low-Power versus High-Power Distance

In low-power distance cultures, according to Hofstede (2009), people relate to one another more as equals and less as a reflection of dominant or subordinate roles, regardless of their actual formal roles as employee and manager, for example. In a high-power distance culture, you would probably be much less likely to challenge the decision, to provide an alternative, or to give input. If you are working with people from a high-power distance culture, you may need to take extra care to elicit feedback and involve them in the discussion because their cultural framework may preclude their participation. They may have learned that less powerful people must accept decisions without comment, even if they have a concern or know there is a significant problem. Unless you are sensitive to cultural orientation and power distance, you may lose valuable information.

While these previous points have quite commonly been used to improve our understanding of divergence, we can also consider Trompenaars’ Model of National Culture Differences as an additional framework for understanding intercultural communication. Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner (1998) created the following description specifically for general business and management by conducting a large-scale survey of 8,841 managers and organization employees from 43 countries. Their model of national culture differences has several dimensions: four orientations refer to how we deal with each other, one refers to time, and one addresses the environment.

1. Universalism vs. Particularism

Universalism is the belief that we can apply ideas and practices everywhere without modification. Particularism is the belief that circumstances dictate how we should apply ideas and practices. It asks, “What is more important, rules or relationships?” Cultures with high universalism see one reality and focus on formal rules. Business meetings are characterized by rational, professional arguments with a “get down to business” attitude.

Trompenaars’ research found high universalism in the United States, Canada, UK, Australia, Germany, and Sweden. Cultures with high particularism view reality more subjectively and place a greater emphasis on relationships. It is important to get to know the people you are doing business with during meetings in a particularist environment. Someone from a universalist culture is wise not to dismiss personal meanderings as irrelevant or mere small talk during business meetings. Countries that have high particularism include Venezuela, Indonesia, China, South Korea, and Russia.

2. Neutral vs. Emotional

People from a neutral culture hold their emotions in check, while those in an emotional culture express their feelings openly. The Japanese and British cultures are neutral cultures. Examples of high emotional cultures include the Netherlands, Mexico, Italy, Israel, and Spain. In emotional cultures, people often smile, talk loudly, and greet each other with enthusiasm. When people from a neutral culture do business in an emotional culture, they should be ready for an animated and boisterous meeting and try to respond warmly. Those from an emotional culture doing business in a neutral culture should not be put off by a lack of emotion.

3. Specific vs. Diffuse

This category examines how individuals separate their personal and public lives. In a “specific” culture, individuals readily share their large public space and lives with others. They guard a small private space closely, which they only share with close friends and associates. In a “diffuse” culture, public and private space have less defined boundaries. Individuals guard their public space carefully because those who enter their public space can easily also enter their private space. Fred Luthans and Jonathan Doh (2021) gives the following example:

American students address their university professor as “Doctor Smith” in a university setting, but others often call the professor by their first name when shopping at a store and other public settings. His status changes because, according to American cultural values, people have large public spaces and often conduct themselves differently depending on their public role. Bob has a private space that is off-limits to students who must call him “Doctor Smith” in class.

In highly-diffuse cultures, people have a similar public and private life. In Germany, people will address a university professor formally, as Herr Professor Doktor Schmidt, at the university, local market, and bowling alley. People maintain a great deal of formality.

4. Achievement vs. Ascription

In an achievement culture, people are accorded status based on how well they perform. In an ascription culture, status is based on who or what a person is. Great attention is paid to one’s title and societal status. Do you have to prove yourself to obtain status, or does a person receive it? Achievement cultures include the United States, Austria, Israel, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Some ascription cultures are Venezuela, Indonesia, and China.

When people from an achievement culture do business in an ascription culture, it is important to have older, senior members with formal titles, and respect should be shown to their counterparts. However, for an ascription culture doing business in an achievement culture, it is important to bring knowledgeable members who can prove to be proficient to other groups, and respect should be shown for the knowledge and information of their counterparts.

5. Sequential versus synchronous time

As the Halls had discovered, time can be experienced differently by various cultures. Trompenaars discovered that a more literal and specific experience and measure of time is the sequential one: minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, years. Cultures that experience time sequentially are very time-conscious, valuing time as a scarce commodity. However, other cultures may experience time more synchronously. As suggested by this term, “lots can happen at the same time,” the experience of time can be multi-dimensional as the past, present, and future are experienced in an interconnected flow (MindTools, n.d.).

6. Internal direction versus outer direction

The environment also plays an important part in how we experience culture: either in an internal-directed or outer-directed manner. How you perceive the environment will determine how you proceed in decision-making and in your actions. Internal-directed cultures believe that they can control their world; whereas outer-directed cultures believe that forces outside of their control affect their work (MindTools, n.d.). This belief system will affect how work is completed in teams.

Read the following Harvard Business Review article: Research: The Biggest Culture Gaps Are Within Countries, Not Between Them

Improving Your Intercultural Competence

As Edward Hall notes, experience has value. If you do not know a culture, you should consider learning more about it firsthand if possible. The people you interact with may not be representative of the culture as a whole, but that is not to say that what you learn from them lacks validity. Quite the contrary; Hall asserts that you can, in fact, learn something without understanding everything, and given the dynamic nature of communication and culture, who is to say that your lessons will not serve you well? Consider a study abroad experience if that is an option for you, or learn from an international student. Be open to new ideas and experiences, and start investigating. Many have gone before you, and today, unlike in generations past, much of the information is accessible. Your experiences will allow you to learn about another culture and yourself, and help you to avoid prejudice.

OpenMed (n.d.) suggests: “for an individual to handle intercultural relationships well, it is necessary to have (a) adequate knowledge of the cultures of contact, (b) cognitive skills to develop positive interpersonal relationships, and (c) problem solving and relationship building skills (Maya Jariego, 2002; Maya Jariego, Holgado & Santolaya, 2006).” See Table 5.4.1 for an overview of eight intercultural competencies that facilitate communication.

Table 5.5.1 8 Skills for effective intercultural communication (partially adapted from OpenMed, n.d.)

|

How can you prepare to work with people from cultures different than your own? Start by doing your homework. People are, for the most part, kind and understanding, so if you make some mistakes along the way, be kind to yourself. Reflect on what happened, learn from it, and move on. Most people are keen to share their culture with others, so your guests will be happy to explain various practices to you.

Content for this chapter has been remixed and partially adapted from a variety of OER sources including but not limited to the following texts:

- Business Writing for Everyone, Cruthers, (2020).

- Communication in the Real World, University of Minnesota (2016).

- Introduction to Professional Communication, Ashman, (2018).

Other texts are included in the References.

References

Allport, G. W. (1958, December). Personality: Normal and abnormal. The Sociological Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1958.tb01072.x

Ashman, M. (2018). Introduction to professional communication. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/professionalcomms/chapter/7-5-intercultural-communication/

Berger, C.R. & Calabrese, R.J. (1975). Some exploration in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human communication research March 2006 1(2):99 – 112. DOI:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1975.tb00258.x

Caldararu, A; Clements, J.; Gayle, R.; Hamer, C.; & MacMinn Varvos, M. (2021). What is culture and intercultural competence? Canadian settlement in action: History and future. NorQuest College. https://openeducationalberta.ca/settlement

Chen, G-M. & Starosta, W. (2000). The development and validation of the intercultural sensitivity scale. Human Communication, Vol. 3, pp 1-5.

Collins, S. (2021). High context and low context communication [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1vgRBENL5es

Confederation College & Paterson Library Commons. (2021). Key terms. Intercultural business communication. OER. CC 4.0. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/communications/chapter/key-terms/

Cruthers, A. (2020). Business writing for everyone. OER. CC 4.0. https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/businesswriting/chapter/intercultural-communication/

Dingwall, J.R.; Labrie, C.; McLennon, T.; & Underwood, L. (n.d.). Professional Communications. OER. CC 4.0. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/profcommsontario/

Extenda Touch. (2021). Cultural Competence [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ugzWjl2tv0

Hall, E.T. & Hall, M. R. (1987). Hidden differences: Doing business with the Japanese. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday.

Hammer, M.R. (2009). The Intercultural Development Inventory. In M.A. Moodian (Ed.). Contemporary leadership and intercultural competence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1982). Culture’s consequences. (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2009, June). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede Model in context. Online readings in psychology and culture (Unit 17, Chapter 14). International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology.

Little, W. (2013, 2016). Introduction to sociology. (2nd Canadian Edition.) https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology2ndedition/chapter/chapter-3-culture/

Luthans, F. & Doh, J. (2021). International management: Culture, strategy, and behavior. McGraw Hill.

Leeds-Hurwitz, W. (1990). Notes in the history of intercultural communication: The Foreign Service institute and the mandate for intercultural training. Quarterly Journal of Speech. Vol. 6(3).

Lindner, M. (2013). Edward T. Hall’s cultural iceberg. Prezi presentation retrieved from https://prezi.com/y4biykjasxhw/edward-t-halls-cultural-iceberg/?utm_source=prezi-view&utm_medium=ending-bar&utm_content=Title-link&utm_campaign=ending-bar-tryout.

Martin, J. N., and Thomas K. Nakayama, Intercultural communication in contexts, 5th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 4.

Maya Jariego, I. (2002). Estrategias de entrenamiento de las habilidades de comunicación intercultural. Portularia. Revista de Trabajo Social, 2, 91-108.

Maya Jariego, I., Holgado, D. & Santolaya, F. J. (2006). Diversidad en el trabajo: estrategias de mediación intercultural [Multimedia]. Sevilla: Fondo Social Europeo.

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication (p. 10). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

MindTools. (n.d.) The seven dimensions of culture. https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/seven-dimensions.htm

Multicultural Council of Saskatchewan. (2017). Image: Cultural iceberg. https://mcos.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/culture-as-an-iceberg-detailled-handout.pdf

Olds College. (n.d.). Cross-cultural communication. Professional Communications. OER. CC 4.0. By Dingwall, J.R.; Labrie, C.; McLennon, T.; & Underwood, L. Professional Communications. OER. CC 4.0. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/profcommsontario/ https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/profcommsontario/

OpenMed. (n.d.). 8 Skills for effective intercultural communication. In Lesson 4.1 The importance of intercultural communication in Open Education. OER. CC 4.0. https://course.openmedproject.eu/lesson-4-1-the-importance-of-intercultural-communication-in-open-education/

Rogers, E.M. & Steinfatt, R.M. (1999). Intercultural communication. Waveland Press, Incorporated.

Saylor.org. (2020, mod.). Trompenaars model of national cultural differences. BUS403: Negotiations and Conflict Management. OER. CC 3.0. https://learn.saylor.org/mod/page/view.php?id=8170

The seven dimensions of culture: Understanding and managing cultural differences. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/seven-dimensions.htm.

Trompenaars, F. & Hampden-Turner, C. (1998). Riding the waves of culture. McGraw-Hill.

University of Minnesota. (2016). Communication in the real world. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/

Worthy, L.D.; Lavigne, T.; & Romero, F. (2020). Culture and psychology: How people shape and are shaped by culture. OER. CC 4.0. https://open.maricopa.edu/culturepsychology/chapter/defining-culture/

Image Descriptions

Figure 5.4.1 image description: This diagram is showing a large circle with the words Global Village in it and four surrounding circles with the words political, ethical, legal, and economic in them. [Return to Figure 18.6]

Figure 5.4.3 image description: This diagram shows a long arrow pointing to the right and the words long term underneath, short arrow pointing to the left with the words short term underneath. [Return to Figure 18.8]