7.4 Stakeholder Engagement and Consultation

Primary research undertaken when embarking on any large scale project will most likely include “public engagement,” or stakeholder consultation. Public engagement is the broadest term used to describe the increasingly necessary process that companies, organizations, and governments must undertake to achieve a “social license to operate.” Stakeholder engagement includes humans in the decision making process and can range from simply informing the public about plans for a project, to engaging them in more consultative practices like getting input and feedback from various groups, and even to empowering key community stakeholders in the final decisions.

For projects that have social, economic, and environmental impacts, and especially for those that foster an Indigenous World View, respect for the Sustainable Development Goals, respect for the rights of Indigenous peoples, and a commitment to social change, stakeholder consultation is an increasingly critical part of the planning stage. Creating an understanding of how projects will affect a wide variety of stakeholders is beneficial for both the company initiating the project and the people who will be affected by it. Listening to stakeholder feedback and concerns can be helpful in identifying and mitigating risks that could otherwise slow down or even derail a project. It can also be an opportunity to build into the project values and actions that work towards improving environmental conditions as well as uplifting communities and the individuals who belong there. For stakeholders, the consultation process creates an opportunity to be informed, as well as to inform the company about local contexts that may not be obvious, to raise issues and concerns, and to help shape the objectives and outcomes of the project.

What is a Stakeholder?

Stakeholders include any individual or group who may have a direct or indirect “stake” in the project – anyone who can be affected by it, or who can have an effect on the actions or decisions of the company, organization, or government. They can also be people who are simply interested in the matter, but more often they are potential beneficiaries or risk-bearers. They can be internal – people from within the company or organization (owners, managers, employees, shareholders, volunteers, interns, students, etc.) – and external, such as community members or groups, investors, suppliers, consumers, policy makers, etc. Increasingly, arguments are being made for considering non-human stakeholders such as the natural environment (Driscoll & Starik, 2004). The following video, Identifying Stakeholders (2018) further explains the process of identifying stakeholders.

Stakeholders can contribute significantly to the decision-making and problem-solving processes. People most affected by the problem and most directly impacted by its effects can help you

- understand the context, issues and potential impacts,

- determine your focus, scope, and objectives for solutions, and

- establish whether further research is needed into the problem.

People who are attempting to solve the problem can help you

- refine, refocus, prioritize solution ideas,

- define necessary steps to achieving them, and

- implement solutions, provide key data, resources, etc.

There are also people who could help solve the problem, but lack awareness of the problem or their potential role. Consultation processes help create the awareness of the project to potentially get these people involved during its early stages.

Knowledge Check

Stakeholder Mapping

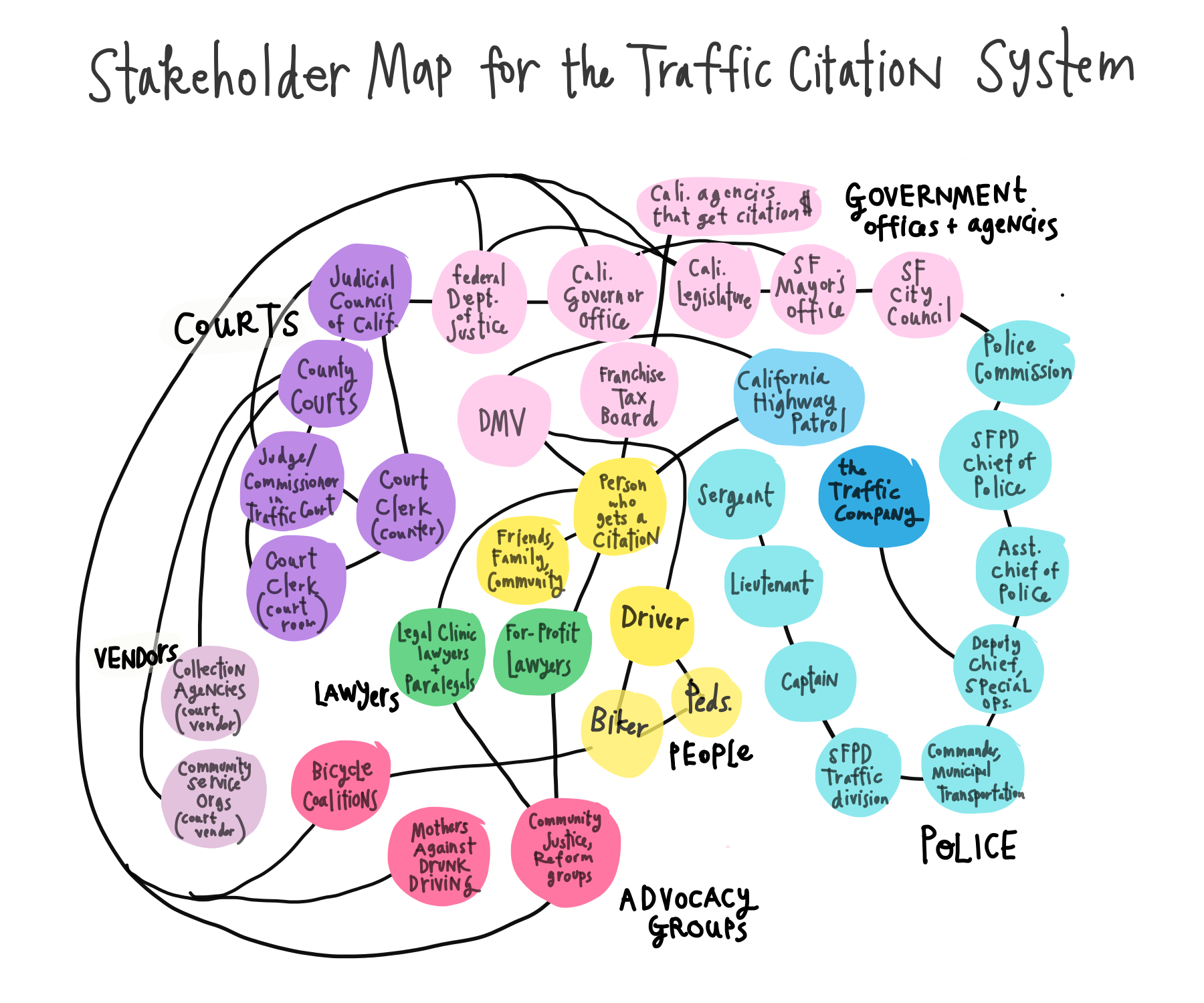

The more a stakeholder group will be materially affected by the proposed project, the more important it is for them to be identified, properly informed, and encouraged to participate in the consultation process. Determining who the various stakeholders are, as well as their level of interest in the project, the potential impact it will have on them, and the power they have to shape the process and outcome is critical. You might start by brainstorming or mind-mapping all the stakeholders you can think of. See Figure 7.4.1 as an example.

LLMs can be used for the mapping process and can reveal stakeholders that you would not think of on your own. To enlist the LLM for assistance follow this process:

Asking the LLM to Generate a Differentiated List of Stakeholders

You can adapt the following example to create a prompt that would assist in identifying stakeholders using an LLM. For the process to be effective, you will need to include specific information about the proposed project or issue, being mindful of your company’s confidentiality policy.

The City of Toronto is thinking of implementing an automated traffic citation system. Before implementation, the City will be consulting with various community stakeholders, including small and large businesses, residents, local community groups, health care and social work agencies, and Indigenous groups. The City will also include in the consultation process law enforcement and potential vendors. Please help me to develop a categorized list of potential stakeholders for this project. I want to classify those who will offer strong support, who would be neutral, and those in opposition.

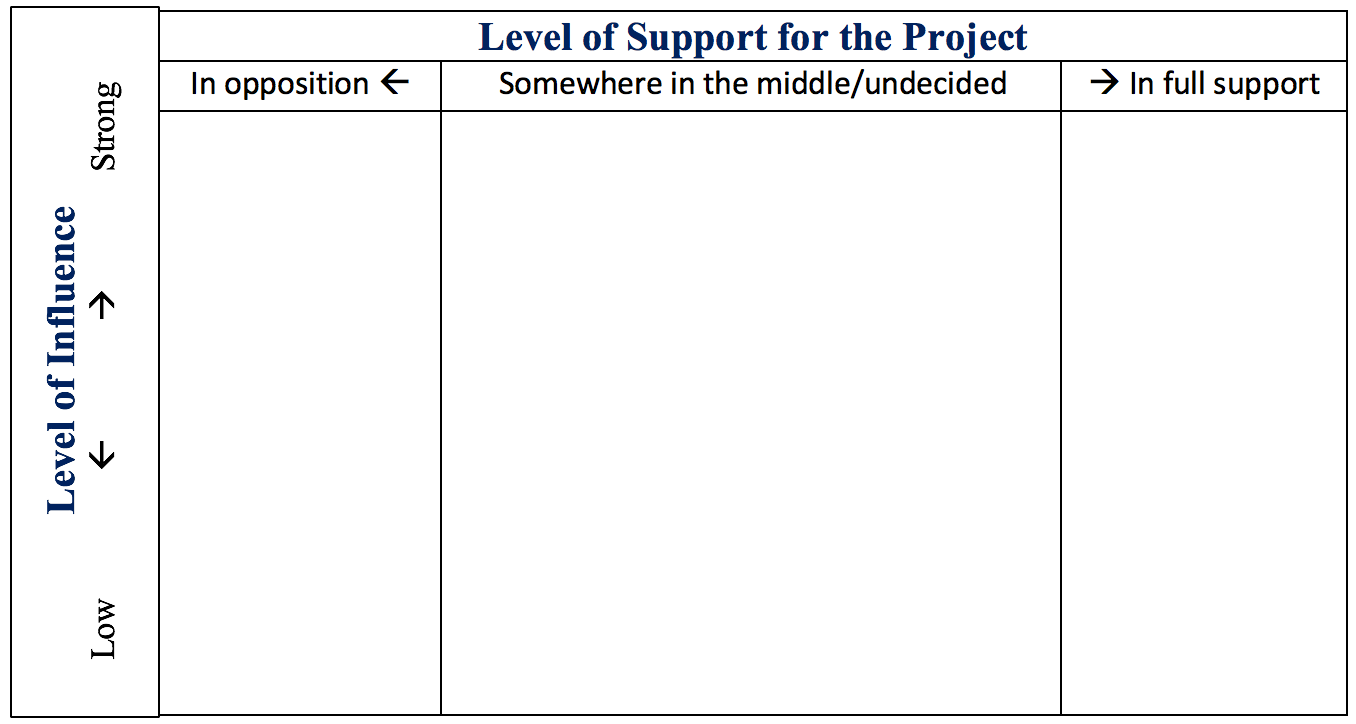

Once stakeholders who may be impacted have been identified, they can be organized into categories or a matrix. One standard method of organizing stakeholders is to determine which are likely to be in support of the project and which are likely to oppose it, and then determine how much power or influence each of those groups has (see Figure 7.4.2 for a visualization of such a matrix).

For example, a mayor of a community has a strong level of influence. If the mayor is in full support of the project, this stakeholder would go in the top right corner of the matrix. Someone who is deeply opposed to the project, but has little influence or power, would go at the bottom left corner.

A matrix like this can help you determine what level of engagement is warranted: where efforts to “consult and involve” might be most needed and most effective, or where more efforts to simply “inform” might be most useful. You might also consider the stakeholders’ level of knowledge on the issue, level of commitment (whether in support or opposed), and resources available.

As you proceed through the stakeholder mapping and especially when using an LLM to assist, be alert for the potential for bias and exclusion. The process is intended to draw as many relevant stakeholders into the consultation. In addition, there may be other factors that should be included in the matrix, so think beyond the boundaries of this example. The factors will be determined by the project and populations involved. Being aware of personal, group, and institutional bias along with contextual variables, for example, will help with keeping a more open mindset and account for a multitude of insights needed to proceed thoroughly.

Levels of Stakeholder Engagement

Levels of engagement can range from simply informing people about what you plan to do to actively seeking consent and placing the final decision in their hands. This range, presented in Figure 7.4.3, is typically presented as a “spectrum” or continuum of engagement from the least to most amount of engagement with stakeholders.

These components are briefly described below:

- Inform: Provide stakeholders with balanced and objective information to help them understand the project, the problem, and the solution alternatives. (There is no opportunity for stakeholder input or decision-making.)

- Consult: Gather feedback on the information given. The level of input can range from minimal interaction (online surveys, etc.) to extensive. It can be a one-time contribution or ongoing/iterative opportunities to give feedback to be considered in the decision-making process.

- Involve: Work directly with stakeholders during the process to ensure that their concerns and desired outcomes are fully understood and taken into account. Final decisions are still made by the consulting organization, but with well-considered input from stakeholders.

- Collaborate: Partner with stakeholders at each stage of decision-making, including developing alternative solution ideas and choosing the preferred solution together. The goal is to achieve consensus regarding decisions.

- Empower: Place final decision-making power in the hands of stakeholders. Voting ballots and referenda are common examples. This level of stakeholder engagement is rare and usually includes a small number of people who represent important stakeholder groups.

Review the following video, What is Stakeholder Engagement? (2020), for an additional overview of this process.

Depending on the type of project, the potential impacts and the types and needs of stakeholders, you may engage in a number of levels and strategies of engagement across this spectrum using a variety of different methods. Your approach may focus on one or several of these as shown in Table 7.4.1:

Table 7.4.1 Typical tools for public engagement

| Inform | Consult | Involve / Collaborate / Empower |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Knowledge Check

The Consultation Process: Basic Steps

There is no single “right” way of consulting with stakeholders. Each situation will be different so each consultation process will be context-specific and will require a detailed plan. A poorly planned consultation process can lead to a lack of trust between stakeholders and the company. Therefore, it is critical that the process be carefully mapped out in advance, and that preliminary work is done to determine the needs and goals of the process and the stakeholders involved. In particular, ensure that whatever tools you use are fully accessible to all the stakeholders you plan to consult. For example, an online survey is not of much use to a community that lacks robust Wi-Fi infrastructure. Consider the following steps to structure your consultation process:

- Situation Assessment: Who needs to be consulted about what and why? Define internal and external stakeholders, determine their level of involvement, interest level, and potential impact, their needs and conditions for effective engagement.

- Goal-setting: What is your strategic purpose for consulting with stakeholders at this phase of the project? Define clear understandable goals and objectives for the role of stakeholders in the decision-making process. Determine what questions, concerns, and goals the stakeholders will have and how these can be integrated into the process. Integrate applicable Sustainable Development Goals from the outset so they are not treated as an afterthought.

- Planning/Requirements: Based on situation assessment and goals, determine what engagement strategies to use and how to implement them to best achieve these goals. Ensure that strategies consider issues of accessibility and inclusivity and consider vulnerable populations. Consider legal or regulatory requirements, policies, or conditions that need to be met. For example, because the research will involve humans, the project should be approved by a Research Ethics Board prior to engagement with the public. (For more information on research involving human subjects, go to Chapter 7.5.) During this phase, you should also determine how you will collect, record, track, analyze and disseminate the data.

- Process and Event Management: In this phase, you will devise strategies to keep the planned activities moving forward and on-track, and adjust strategies as needed. Be sure to keep track of all documentation.

- Evaluation: Design an evaluation metric to gauge the success of the engagement strategies; collect, analyze, and act on the data collected throughout the process. Determine how will you report the results of the engagement process back to the stakeholders.

In situations when projects will affect Indigenous communities, land, and resources, you are obligated by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights to apply the practice of “free, prior, and informed consent of indigenous peoples” (OHCHR, 2013).

Communicating Effectively in Stakeholder Engagement

Effective communication is the foundation of stakeholder consultation. The ability to create and distribute effective information, develop meaningful relationships, build trust, and listen to public input is essential.

The basic communication skills required for any successful stakeholder engagement project include:

- Effective Writing: the ability to create clear and concise written messages using plain language and structural conventions.

- Visual Rhetoric: the ability to combine words, images, and graphics to support, clarify, and illustrate ideas and make complex issues understandable to a general audience.

- Public Speaking/Presenting: the ability to present information to large audiences in a comfortable and understandable way. The ability to create effective visual information that increases the audience’s understanding.

- Interpersonal and Intercultural Skills: the ability to relate to people in face-to-face situations, to make them feel comfortable and secure, and to be mindful of cultural factors that may affect interest level, accessibility, impact, values, or opinions.

- Collaboration Skills: the ability to work effectively with little friction with team members. Collaboration typically involves frequent and open communication, cooperation, good will, information sharing, problem-solving, and empathy.

- Active Listening: the ability to focus on the speaker and portray the behaviours that provide them with the time and safety needed to be heard and understood. The ability to report back accurately and fully what you have heard from participants.

Note that when communicating with Indigenous Elders and Chiefs, specific protocols should be followed to honour the traditions, culture, and history of Indigenous people.

Caring for Your Stakeholders: Introductory Principles

Most often, stakeholder engagement and consultation will obviously involve the participation of humans since they are the ones who will be providing the input needed to move a project forward. Because some past consultations have been conducted in ways that inflicted harm on participants, strict guidelines have been developed for the ethical treatment of humans in research. When first embarking on a human-involved research project, you must first check-in with your professor or workplace manager, who will determine if an application for approval must be submitted to the Research Ethics Board (REB) at the institution or organization. This approval process helps to ensure that the research methods as well as data collection, storage, and use will all align with ethical practices and laws.

The basic guidelines in the chart below are typically part of the process of ensuring that you are transparent and careful with how you approach your research and human participants and subjects. Be reminded that when gathering, storing, and using data, especially those gathered from people, you must abide by the Canadian federal and provincial privacy laws. Please refer to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) and Ontario’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) for more information. See more about protecting people’s information in Chapter 7.5 Research Ethics.

Recruiting Participants

When recruiting potential participants, you must give them the following information before you begin:

- Researcher name(s): Inform them of your name and contact information

- Affiliation: Provide a) the name of your institution or organization, b) your department, and c) your instructor’s or manager’s name and contact information

- Project Description: Include a brief description of the project in lay language that can be understood by the participants and clearly identifies the problem being addressed; mention the names of key people on your project team

- Purpose: Describe the purpose of your research or consultation/engagement project (objectives), and the benefits you hope will come from this project (overall goal). Your activity should not involve any deception (e.g., claiming to be gathering one kind of information, such as “do you prefer blue or green widgets?”, but actually gathering another kind, such as “what percentage of the population is blue/green colour blind?”). See Chapter 7.5 for more on the topic of ethics violations.

- Use of information: Inform participants of the way in which the results will be presented and/or disseminated.

Informed Consent

You must gain the informed consent of the people you will be surveying, interviewing, or observing. This can be done using a consent form they can sign in person, or through an “implied consent” statement such as on an electronic survey. The consent form should include all the information in the “recruiting” section above. In addition, you should

- include a full description of all data collection methods, procedures, and instruments, as well as expectations regarding the amount of time required for participation

- inform participants that their participation is voluntary and that they may withdraw at any time without consequence, even if they have not completed the survey or interview,

- disclose any and all risks or discomfort that participation in the study may involve, and how these risks or discomfort will be addressed, and

- ensure that all participants are adults (19 years of age or older) and fully capable of giving consent; do not recruit from vulnerable or at-risk groups, and do not collect demographic data regarding age, gender, or any other information not relevant to the study (e.g., phone numbers, medications they are taking, whether they have a criminal records, etc.).

- include a method by which the participants can signal their consent or include an implied consent statement as as the following: “By completing and submitting this survey, you are indicating your consent for the collection and use of information provided.”

Managing the Data

Participants should be told what will happen to the data you gather:

- Survey data are anonymous if you do not track who submitted responses. In anonymous surveys, let participants know that once they submit their survey, it cannot be retrieved and removed from the overall results.

- Inform participants of the means by which their anonymity will be protected and data will be kept confidential as well as how the raw data, including tapes, digital recordings, notes, and other types of data will be disposed of at the end of the project.

- Let survey participants know a) that your research results will be reported without their names and identifiers, b) where the data will be stored, c) how it will be “published”, and d) what will happen to the raw data once your project is complete.

- Let interview participants know how their information will be used and if their names will be included or cited.

There may be additional issues that must addressed, such as accessibility and cultural considerations, but those listed above are typically included. If you are unsure whether a particular line of inquiry or method of data collection requires ethics approval, you should ask your instructor or manager. Most importantly, you should always be completely transparent and honest about what and how you are researching.

It may seem like “a lot of fuss” to go through simply to ask people whether they prefer blue widgets or green widgets, but there are important reasons for these guidelines. People participating in your research need to be reassured that you are doing this for a legitimate reason and that the information you are gathering will be treated with respect and care.

For more information about research ethics, see Chapter 7.5.

Asking Questions in Surveys and Interviews (adapted from Divjak, 2007-2025)

Questionnaire Surveys

Invented by Sir Francis Galton, a questionnaire is a research instrument consisting of a set of questions (items) intended to capture responses from respondents in a standardized manner. Questions should be designed in such a way that respondents are able to read, understand, and respond to them in a meaningful way. Surveys are commonly used to gather information from stakeholders because they are efficient in gathering lots of data, are of low cost, and, when designed well, can reveal valuable information.

Here are the steps involved applying a survey in your study:

Constructing a survey questionnaire is an art. Numerous decisions must be made about the content of questions, their wording, format, and sequencing, all of which can have important consequences for the survey responses. In the process, you must use the ethical principles discussed in Chapter 7.5 to guide you. Primarily, you would want to avoid doing anything that would cause physical or emotional harm to your participants. For example, carefully word sensitive or controversial questions and avoid inserting unintended bias or asking leading questions. You want to design questions to get meaningful and accurate responses rather than ambiguous information that is impossible to quantify or analyze. As a result, constructing a survey questionnaire is not a linear straightforward process. Instead, it is an iterative process, in which you would most probably need to produce several versions of the questionnaire and revise them a few times before coming up with a final version of your questionnaire.

Where to start? To write effective survey questions begin by identifying what you wish to know. In other words, refer to the research questions (general and specific) that have guided your research process to ensure that you collect all relevant data through the survey.

Let’s say you want to understand how students make a successful transition from high school to college. Perhaps you wish to identify which students are comparatively more or less successful in this transition and which factors contribute to students’ success or lack thereof. Let’s suppose you have set up the following general research question: Which factors contribute to students’ success or failure in the process of transition from high school to university? To understand which factors shape (un)successful students’ transitions to university, you’ll need to include questions in your survey about all the possible factors that could affect this transition. Consulting the literature on the topic will certainly help, but you should also take the time to do some brainstorming on your own and to talk with others about what they think may be important.

Perhaps time or space limitations won’t allow you to include every item you’ve listed, so rank your questions so as to include those that are the most important.

LLMs can assist in drafting survey questions when they are provided with specific information about your project. Remember that the LLM output will often produce generalized information and content, so a careful review of the questions and revision for your specific research goals is essential.

Asking the LLM to Draft Survey Questions (adapted from Microsoft Copilot, 2025)

Use the following key elements in your prompt when asking an LLM to draft survey questions:

- Purpose of the Survey: Clearly state the objective of the survey. This helps the LLM understand the context and generate relevant questions.

- Example: “Create survey questions that will help to assess the inclusivity of our workplace environment [specify the type of business or industry].”

- Target Audience: Specify who the survey is intended to address (respondents). This ensures the questions are appropriate for the respondents.

- Example: “The survey is for all employees across different departments and levels.”

- Type of Questions: Indicate the types of questions you want (e.g., multiple choice, Likert scale, open-ended*).

- Example: “Include a mix of multiple choice, Likert scale, and open-ended questions.”*Find out about question types in the sections below.

- Key Topics or Areas: List the main topics or areas you want to cover in the survey.

- Example: “Focus on experiences of inclusion, diversity, and equity in the workplace.”

- Number of Questions: Specify the desired number of questions.

- Example: “Generate 12 questions.”

- Tone and Language: Mention any specific tone or language preferences.

- Example: “Use a respectful and inclusive tone.”

- Additional Instructions: Include any other specific instructions or constraints.

-

- Example: “Ensure questions are sensitive to diverse backgrounds and identities.”

Here’s a sample prompt incorporating these elements:

Prompt for LLM to Create Survey Questions

Help me to develop a survey to assess the inclusivity of our workplace environment. The survey is intended for all employees across different departments and levels. Include a mix of multiple choice, Likert scale, and open-ended questions. I want to focus on experiences of inclusion, diversity, and equity in the workplace. Guide me as I generate 12 questions using a respectful and inclusive tone. Ensure that I develop questions are sensitive to diverse backgrounds and identities.

By including these elements, you can provide clear and comprehensive instructions to LLMs, ensuring the generated survey questions are relevant and effective in assessing the topic area you are investigating.

Response Formats

Questions may be unstructured (open-ended) or structured (closed-ended). Unstructured questions ask respondents to provide a response in their own words, while structured questions ask respondents to select an answer from a given set of choices (response options).

Generally, structured (closed-ended) questions predominate in surveys but sometimes survey researchers include open-ended questions as a way to gather additional details from respondents. An open-ended question does not include response options; instead, respondents are asked to reply to the question using their own words. These questions are generally used to find out more about a survey participant’s experiences or feelings about the topic. If, for example, a survey includes closed-ended questions asking respondents to report on their involvement in extracurricular activities during college, an open-ended question could ask respondents why they participated in those activities or what they gained from their participation. While responses to such questions may also be captured using a closed-ended format, allowing participants to share some of their responses in their own words can make the experience of completing the survey more satisfying to them and can reveal motivations or explanations that had not occurred to the researcher.

There shouldn’t be too many unstructured (open-ended) questions included in surveys, as respondents might be reluctant to write down detailed, elaborated, and in-depth responses to such questions. Apart from that, there are other reasons behind this rationale (e.g., complexity of analyzing open-ended responses, especially in the case of large samples).

Designing Good Survey Questions

Responses obtained in survey research are very sensitive to the types of questions asked. Poorly framed or ambiguous questions will likely result in responses with very little value. Every question in a survey should be carefully scrutinized for the following issues:

Is the question clear and understandable?

Survey questions should be stated in clear and straight-forward language, preferably in active voice, and without complicated words or jargon that may not be understood by a typical respondent. The only exception is if your survey is targeted at a specialized group of respondents, such as doctors, lawyers and researchers, who use such jargon in their everyday environment. Make sure that the language you are using is concise and precise; avoid metaphoric expressions.

In the above example of the transition to college, the criterion of clarity would mean that respondents must understand what exactly you mean by “transition to college”. If you are going to use that phrase in your survey you need to clearly define what the phrase refers to.

Also, pay attention to the usage of words that may have different meanings, e.g., in different parts of the country or among different segments of survey respondents. Let’s take an example of the word “wicked”. This term could be associated with evil; however, it in contemporary subcultures, it means “very,” “really,” “extremely” (Nikki, 2004).

Is the question worded in a negative manner?

Negatively-worded questions should be avoided, and in all cases, avoid double-negatives. Such questions as “Should your local government not raise taxes?” and “Did you not drink during your first semester of college?” tend to confuse many respondents and lead to inaccurate responses. Instead, you could ask: “What is your opinion on your local government intention to raise taxes?” and “Did you drink alcohol in your first semester of college?” These examples are obvious, but hopefully clearly illustrate the importance of careful wording for questions.

Is the question ambiguous?

Survey questions should not contain words or expressions that may be interpreted differently by different respondents (e.g., words like “any” or “just”). For instance, if you ask a respondent “What is your annual income?”, it is unclear whether you referring to salary/wages, or also dividend, rental, and other income, whether you referring to personal income, family income (including spouse’s wages), or personal and business income? Different interpretation by various respondents will lead to incomparable responses that cannot be interpreted correctly.

Does the question have biased or value-laden words?

Bias refers to any property of a question that encourages subjects to answer in a certain way. Kenneth Rasinky (1989, cited in Bhattacherjee, 2012) examined several studies on people’s attitude toward government spending, and observed that respondents tend to indicate stronger support for “assistance to the poor” and less for “welfare”, even though both terms had the same meaning. In this study, more support was also observed for “halting rising crime rate” (and less for “law enforcement”), “solving problems of big cities” (and less for “assistance to big cities”), and “dealing with drug addiction” (and less for “drug rehabilitation”). A biased language or tone tends to skew observed responses. It is often difficult to anticipate in advance the biasing wording, but to the greatest extent possible, survey questions should be carefully scrutinized to avoid biased language.

Is the question on two topics?

Avoid creating questions that are on two topics because the respondent can only respond to one of the topics at a time. For example, “Are you satisfied with the hardware and software provided for your work?” In this example, how should a respondent answer if he/she is satisfied with the hardware but not with the software or vice versa? It is always advisable to separate two-topic questions into separate questions: (1) “Are you satisfied with the hardware provided for your work?” and (2) “Are you satisfied with the software provided for your work?” Another example of a confusing question: “Does your family favour public television?” Some people in the family may favour public TV for themselves, but favour certain cable TV programs such as Sesame Street for their children. Ensure that your questions clearly address one topic.

Is the question too general?

Sometimes, questions that are too general may not accurately convey respondents’ perceptions. If you asked someone how they liked a certain book and provide a response scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely well”, if that person selected “extremely well”, what does that mean? Instead, ask more specific behavioural questions, such as “Will you recommend this book to others?” or “Do you plan to read other books by the same author?” Likewise, instead of asking “How big is your firm?” (which may be interpreted differently by respondents), ask “How many people work for your firm, and/or what is the annual revenues of your firm?” which are both measures of firm size.

Is the question asking for too much detail?

Avoid asking for detail that serves no specific research purpose. For instance, do you need to have the age of each child in a household or is just the number of children in the household acceptable? If unsure, however, it is better to err on the side of details than generality.

Is the question leading or presumptuous?

If you ask, “What do you see are the benefits of a tax cut?” you are presuming that the respondent sees the tax cut as beneficial. But many people may not view tax cuts as being beneficial because tax cuts generally lead to lesser funding for public schools, larger class sizes, and fewer public services such as police, ambulance, and fire service. So avoid leading or presumptuous questions. Instead, first ask about the perception of the tax cut and then direct the question on the benefits of the tax cut only to those respondents who perceive tax cut as beneficial (see the section on filter questions below).

Is the question relevant only for particular segments of respondents?

If you decide to pose questions about matters with which only a portion of respondents will have had experience, introduce a filter question into your survey. A filter question is designed to identify a subset of survey respondents who are asked additional questions that are not relevant to the entire sample. Perhaps in your survey on the transition to college you want to know whether substance use plays any role in students’ transitions. You may ask students how often they drank alcohol during their first semester of college. But this assumes that all students drank. Certainly, some may have abstained, and it wouldn’t make any sense to ask the nondrinkers how often they drank. So the filter would direct those who drank to additional questions, while other respondents proceed through the new question.

Is the question on a hypothetical situation?

A popular question in many television game shows is “If you won a million dollars on this show, how do you plan to spend it?” Most respondents have never been faced with such an amount of money and have never thought about it, and so their answers tend to be quite random, such as take a tour around the world, buy a restaurant, spend on education, save for retirement, help parents or children, or have a lavish wedding. Hypothetical questions have imaginary answers, which cannot be used for making scientific inferences.

Do respondents have the information needed to correctly answer the question?

Often, we assume that subjects have the necessary information to answer a question, when in reality, they do not. Even if responses are obtained, in such case, the responses tend to be inaccurate, given the respondents’ lack of knowledge about the question being asked. For instance, we should not ask the CEO of a company about day-to-day operational details about which they may have no knowledge.

In the example of the transition to college, the respondents must have actually experienced the transition to college themselves in order for them to be able to answer the survey questions.

Does the question tend to elicit socially desirable answers?

In survey research, social desirability refers to the idea that respondents will try to answer questions in a way that will present them in a favourable light. Perhaps we decide that to understand the transition to college, we need to know whether respondents ever cheated on an exam in high school or college. We all know that cheating on exams is generally frowned upon. So, it may be difficult to get people to admit to such cheating on a survey. But if you can guarantee respondents’ confidentiality, or even better, their anonymity, chances are much better that they will be honest about having engaged in this socially undesirable behaviour. Another way to avoid problems of social desirability is to try to phrase difficult questions in the most benign way possible. Earl Babbie (2010) offers a useful suggestion for helping you do this—simply imagine how you would feel responding to your survey questions. If you would be uncomfortable, chances are others would as well.

In sum, in order to pose effective and proper survey questions, you should do the following:

- Identify what it is you wish to find out (define proper research questions).

- Keep questions clear and simple.

- Make questions relevant to respondents.

- Use filter questions when necessary.

- Avoid questions that are likely to confuse respondents such as those that use double negatives, use culturally specific terms, or pose more than one question in the form of a single question.

- Imagine how you would feel responding to questions.

Get feedback, especially from the people who resemble those in your sample (small scale pilot study), before you send it to your respondents.

Response Options

In the case of structured (closed-ended) questions you should carefully consider the response options. Response options are the answers that you provide to the people taking your survey, and they are usually captured using one of the following response formats:

- Dichotomous response, where respondents are asked to select one of two possible choices, such as true/false, yes/no, or agree/disagree. An example of such a question is: Do you think that the death penalty is justified under some circumstances? (circle one): yes / no.

- Nominal response, where respondents are presented with more than two unordered options, such as: What is your industry of employment?— manufacturing / consumer services / retail / education / healthcare / tourism & hospitality / other

- Ordinal response, where respondents have more than two ordered options, such as: What is your highest level of education?—high school / college degree / graduate studies.

- Interval-level response, where respondents are presented with a 5-point or 7-point interval scale, such as: To what extent do you agree with the following statement [insert statement]: strongly disagree / disagree / neither agree nor disagree / agree / strongly agree.

- Continuous response, where respondents enter a continuous (ratio-scaled) value with a meaningful zero point, such as their age, weight or year of birth (How old are you? What is your weight in kilograms? Which year you were born?). These responses generally tend to be of the fill-in-the blanks type.

- Rank ordering the response options, such as “Rank the five elements that influenced your choice of the university program from the most to the least influential; assign number 1 to the most influential element and number 5 to the least influential element; properly assign numbers 2-4 to the rest of the elements.”

Generally, respondents will be asked to choose a single (or best) response to each question you pose, though certainly it makes sense in some cases to instruct respondents to choose multiple response options. One caution to keep in mind when accepting multiple responses to a single question, however, is that doing so may add complexity when it comes to analysing your survey results. Nevertheless, for each closed-ended question, clearly instruct the respondents on the number of response options they are required to choose.

Guidelines for Designing Response Options

Here are a few guidelines worth following when designing the response options.

Ensure that your response options are mutually exclusive. In other words, there should be no overlapping categories in the response options. In the example about the frequency of alcohol consumption, if we ask “On average, how many times per week did you consume alcoholic beverages during your first semester of college?”, we may then provide the following response options: a) less than one time per week, b) 1-2, c) 3-4, d) 5-6, e) 7+. Do you notice that there are no overlapping categories in the response options for these questions?

Create response options that are exhaustive. In other words, every possible response should be covered in the set of response options. In the example shown in the paragraph above, we have covered all possibilities: those who drank, say, an average of once per month can choose the first response option (“less than one time per week”) while those who drank multiple times a day each day of the week can choose the last response option (“7+”). All the possibilities in between these two extremes are covered by the middle three response options. When you are unsure about capturing all response options, you can add the option “other” to the list to enable the respondents to specify their response in their own words. This is particularly useful in case of nominal unorder response options.

If there is a reason to believe that not all respondents would be able to select from the given response options, then add the “not able to answer” or “not applicable to me” response to the response options list, in order to ensure the validity of collected data.

Use a question matrix when answer categories are identical. Using a matrix is a nice way of streamlining response options. A matrix is a question type that lists a set of questions for which the answer categories are all the same (Table 7.4.2). If you have a set of questions for which the response options are all the same, create a matrix rather than posing each question and its response options individually. Not only will this save you some space in your survey but it will also help respondents progress through your survey more easily and quickly.

Table 7.4.2 Sample Question Matrix

| Online learning… | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Nether disagree nor agree | Agree | Strongly agree |

| …is more difficult than traditional in-class learning. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| …only appropriate for part-time employed students. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| …will become predominant mode of learning in the near future. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Ensure that response options are aligned with the question wording and vice versa. For example, if you have a yes/no question type, then you should only provide the yes and no response options (e.g., “Do you support the Prime Minister in his endeavours to foster respectful communication?”–yes/no). If you want to know about the frequency of an event (let’s say the frequency of alcohol consumption during college), then the yes/no question (e.g., “Did you consume alcohol during college?”) would be inappropriate. It would also be inappropriate to have a yes/no question type and ordered response options (e.g. every day in a week, once per week etc.). This is where attention to detail and proofreading skills come into play.

Questionnaire Design

In addition to constructing quality questions and posing clear response options, you’ll also need to think about how to present your written questions and response options to survey respondents. Designing questionnaires takes some thought, and in this section, we’ll discuss what you should think about as you prepare to present your well-constructed survey questions on a questionnaire.

In general, questions should flow logically from one to the next. To achieve the best response rates, questions should flow from the least sensitive to the most sensitive, from the factual and behavioural to the attitudinal, and from the more general to the more specific.

One of the first things to do once you’ve come up with a good set of survey questions is to group those questions thematically. In our example of the transition to college, perhaps we’d have a few questions asking about study habits, others focused on friendships, and still others on exercise and eating habits. Those may be the themes around which we organize our questions. Or perhaps it would make more sense to present any questions we had about precollege life and habits and then present a series of questions about life after beginning college. The point here is to be deliberate about how you present your questions to respondents.

Once you have grouped similar questions together, you’ll need to think about the order in which to present those question groups. Most survey researchers agree that it is best to begin a survey with questions that will want to make respondents continue (Babbie, 2010; Dillman, 2000; Neuman, 2003). In other words, don’t bore respondents, but don’t scare them away either.

There’s some disagreement over where on a survey to place demographic questions such as those about a person’s age, gender, and race. On the one hand, placing them at the beginning of the questionnaire may lead respondents to mistake the purpose of the survey. On the other hand, if your survey deals with some very sensitive or difficult topic, such as workplace racism or sexual harassment, you don’t want to scare respondents away or shock them by beginning with your most intrusive questions. Generally, it’s advisable to put demographic questions in the end of the questionnaire, unless it is required to have them at the beginning, for instance if particular survey questions serve as filter questions.

In truth, the order in which you present questions on a survey is best determined by the unique characteristics of your research—only you, the researcher, and in consultation with colleagues, can determine how best to order your questions. To do so, think about the unique characteristics of your topic, your questions, and most importantly, your sample. Keeping in mind the characteristics and needs of the potential respondents should help guide you as you determine the most appropriate order in which to present your questions.

Also consider the time it will take respondents to complete your questionnaire. Surveys vary in length, from just a page or two to a dozen or more pages, which means they also vary in the time it takes to complete them. How long to make your survey depends on several factors. First, what is it that you wish to know? Wanting to understand how grades vary by gender and year in school certainly requires fewer questions than wanting to know how people’s experiences in college are shaped by demographic characteristics, college attended, housing situation, family background, college major, friendship networks, and extracurricular activities. Even if your research question requires a good number of survey questions, do your best to keep the questionnaire as brief as possible. Any hint that you’ve thrown in unnecessary questions will turn off respondents and may make them not want to complete your survey.

Second, and perhaps more important, consider the amount of time respondents would likely be willing to spend completing your questionnaire? If your respondents are college students, your survey would be taking up valuable study time, so they won’t want to spend more than a few minutes on it. The time that survey researchers ask respondents to spend on questionnaires varies greatly. Some advise that surveys should not take longer than about 15 minutes to complete (cited in Babbie, 2010), others suggest that up to 20 minutes is acceptable (Hopper, 2010). This would be applicable to self-completion surveys, while surveys administered personally face-to-face by an interviewer asking questions, may even take up to an hour or more. As with question order, there is no clear-cut rule for how long a survey should take to complete. The unique characteristics of your study and your sample should be considered in order to determine how long to make your questionnaire.

A good way to estimate the time it will take respondents to complete your questionnaire is through pretesting (piloting). Pretesting allows you to get feedback on your questionnaire so you can improve it before you actually administer it. Pretesting is usually done on a small number of people (e.g., 5 to 10) who resemble your intended sample and to whom you have easy access. By pretesting your questionnaire, you can find out how understandable your questions are, get feedback on question wording and order, find out whether any of your questions are unclear, overreach, or offend, and learn whether there are places where you should have included filter questions, to name just a few of the benefits of pretesting. You can also time pre-testers as they take your survey. Ask them to complete the survey as though they were actually members of your sample. This will give you a good idea about what sort of time estimate to provide respondents when it is administered, and whether you are able to add additional questions/items or need to cut a few questions/items.

Perhaps this goes without saying, but your questionnaire should also be attractive. A messy presentation style can confuse respondents or, at the very least, annoy them. Use survey design tools like Google Forms, Microsoft Forms to create a consistent design and to automate the collection and visualization of the data collected.

In sum, here are some general rules regarding question sequencing and questionnaire design:

- Brainstorm and consult your research to date are two important early steps to take when preparing to write effective survey questions.

- Start with easy non-threatening questions that can be easily recalled.

- Never start with an open-ended question.

- If following an historical sequence of events, follow a chronological order from earliest to latest.

- Ask about one topic at a time (group the questions meaningfully around common topics). When switching topics, use a transition, such as “The next section examines your opinions about …”.

- Make sure that your survey questions will be relevant to all respondents and use filter or contingency questions as needed, such as: “If you answered “yes” to question 5, please proceed to Section 2. If you answered “no” go to Section 3.” Automated surveys will guide respondents to the next question based on the filters provided.

Always pretest your questionnaire before administering it to respondents in a field setting. Such pretesting may uncover ambiguity, lack of clarity, or biases in question wording, which should be eliminated before administering to the intended sample.

Qualitative Interviews

Qualitative interviews are sometimes called intensive or in-depth interviews. These interviews are semi-structured; the researcher has a particular topic about which he or she would like to hear from the respondent, but questions are open-ended and may not be asked in exactly the same way or in exactly the same order to each respondent. In in-depth interviews, the primary aim is to hear from respondents about what they think is important about the topic at hand and to hear it in their own words. In this section, we’ll take a look at how to conduct interviews that are specifically qualitative in nature, and use some of the strengths and weaknesses of this method.

Qualitative interviews might feel more like a conversation than an interview to respondents, but the researcher is in fact usually guiding the conversation with the goal of gathering information from a respondent. A key difference between qualitative and quantitative interviewing is that qualitative interviews contain open-ended questions without response options. Open-ended questions are more demanding of participants than closed-ended questions, for they require participants to come up with their own words, phrases, or sentences to respond. In qualitative interviews you should avoid asking closed-ended questions, such as yes/no questions or questions which are possible to be answered with short replies (e.g., in a couple of words or phrases).

In a qualitative interview, the researcher usually develops a guide in advance that he or she then refers to during the interview (or memorizes in advance of the interview). An interview guide is a list of topics or questions that the interviewer hopes to cover during the course of an interview. It is called a guide because any good interview is a conversation, and one topic can lead to another that is not on your list. Interview guides should outline issues that a researcher feels are likely to be important, but because participants are asked to provide answers in their own words, and to raise points that they believe are important, each interview is likely to flow a little differently. While the opening question in an in-depth interview may be the same across all interviews, from that point on what the participant says will shape how the interview proceeds. Here, excellent listening skills, knowledge of your goals, and an intuitive approach work together to obtain the information you need from the interviewee. It takes a skilled interviewer to be able to ask questions; listen to respondents; and pick up on cues about when to follow up, when to move on, and when to simply let the participant speak without guidance or interruption.

Like in case of a questionnaire surveys, the interview guide should be derived from the research questions of a given research. The specific format of an interview guide (a list of topics or a detailed list of general and additional interview questions) might depend on your style, experience, and comfort level as an interviewer or with your topic. If you are well-experienced in qualitative interviewing and you are highly familiar with the research topic, then it might be enough to prepare the interview guide as a list of potential topics and subtopics to be covered during the interview. But if you are less experienced in qualitative interviewing and/or you are not that familiar with the research topic, then it would be much better to prepare a detailed set of interview questions following research into the relevant issues.

Begin constructing your interview guide by brainstorming all the topics and questions that come to mind when you think about your research question(s). Once you’ve got a pretty good list, you can pare it down by cutting questions and topics that seem redundant and group like questions and topics together. If you haven’t done so yet, you may also want to come up with question and topic headings for your grouped categories. You should also consult the scholarly literature to find out what kinds of questions other interviewers have asked in studies of similar topics.

Also, when preparing the interview guide, it is a good idea to define and separate the general questions from a few extra additional probing questions for each general question. You may use these probing questions if required, such as in instances when the respondent has difficulties answering a given general question, if he/she needs additional guidance, or if you want to dig deeper into the topic. Often, interviewers are left with a few questions that were not asked, which is why prioritizing the questions in a list of most important to least is good practice.

As with quantitative survey research, it is best not to place very sensitive or potentially controversial questions at the very beginning of your qualitative interview guide. You need to give participants the opportunity to become comfortable with the interview process and with you. Finally, get some feedback on your interview guide. Ask your colleagues for some guidance and suggestions once you’ve come up with what you think is a pretty strong guide. Chances are they’ll catch a few things you hadn’t noticed.

In terms of the questions you include on your interview guide, there are a few guidelines worth noting:

Avoid questions that can be answered with a simple yes or no, or if you do choose to include such questions, be sure to include follow-up questions. Remember, one of the benefits of qualitative interviews is that you can ask participants for more information—be sure to do so. While it is a good idea to ask follow-up questions, try to avoid asking “why” as your follow-up question, as this particular question can come off as confrontational, even if that is not how you intend it. Often people won’t know how to respond to “why,” perhaps because they don’t even know why themselves. Instead of “why,” say something like, “Could you tell me a little more about that?” This allows participants to explain themselves further without feeling that they’re being doubted or questioned in a hostile way.

Avoid phrasing your questions in a leading way. For example, rather than asking, “Don’t you think that most employees would rather have a four day work week?” you could ask, “What comes to mind for you when you hear that a four day work week is being considered at our company?”

Collecting and Storing Interview Information

Even after the interview guide is constructed, the interviewer is not yet ready to begin conducting interviews. The researcher next has to decide how to collect and maintain the information. It is probably most common for qualitative interviewers to take audio recordings of the interviews they conduct. Interviews, especially conducted on meeting platforms like Zoom can also now be captured using AI-assisted tools that will provide a video, transcription, and summary of the interview. For in person interviews, recordings can be captured by applications designed for this purpose, such as Otter.ai.

Recording interviews allows the researcher to focus on her or his interaction with the interview participant rather than being distracted by trying to take notes. Of course, not all participants will feel comfortable being recorded and sometimes even the interviewer may feel that the subject is so sensitive that recording would be inappropriate. If this is the case, it is up to the researcher to balance excellent note-taking with exceptional question asking and even better listening. Whether you will be recording your interviews or not (and especially if not), practicing the interview in advance is crucial. Ideally, you’ll find a friend or two willing to participate in a couple of trial runs with you. Even better, you’ll find a friend or two who are similar in at least some ways to your sample. They can give you the best feedback on your questions and your interviewing performance.

In large community projects, such as you would find in real estate developments, rezoning, urban renewal, as well as more local or internal innovation or change, it is always a good idea to involve stakeholders in conversations and consultations. How you design the consultation process will affect it’s success, so be deliberate in your planning. Your stakeholder’s input can be the most valuable asset to any researcher and can guide them in making decisions that will move projects towards the benefit of all affected. Using stakeholder mapping, ethical consultation practices, and effective question design skills will facilitate the process.

Additional Resources

For information on developing stakeholder consultation with indigenous communities, read Part I: Stakeholder Consultation. For a recent and local example of a stakeholder engagement plan, see the University of Victoria’s “Campus Greenway Engagement Plan (University of Victoria Campus Planning and Sustainability, n.d.). A significant step in this plan — a Design Charrette — was implemented in the fall of 2018; the results of that engagement activity, presented in a Summary Report (.pdf) (University of Victoria Campus Planning and Sustainability, 2018), and it resulted in changes and augmentation of the original plan based on stakeholder feedback.

The segment on Asking Survey and Interview Questions was partially adapted from Marko Divjak’s Google Classroom unit (2007-2025) ASKING QUESTIONS IN SURVEYS AND INTERVIEWS | OER Commons

His work consisted of remixing and adapting the following two open educational resources, which were both licensed under CC BY-NC-SA license:

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices. University of South Florida: Scholar Commons (chapter 9). Retrieved from: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=oa_textbooks

Blackstone, A. (2014). Principles of sociological inquiry – Qualitative and quantitative methods (chapters 8 and 9). Retrieved from: http://www.saylor.org/site/textbooks/Principles%20of%20Sociological%20Inquiry.pdf

References

Association of Project Management. (2020). What is stakeholder engagement [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZzqvF9uJ1hA&t=1s

Babbie, E. (2010). The practice of social research (12th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices. University of South Florida: Scholar Commons. Retrieved from: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=oa_textbooks

Clennan, R. (2007, April 24). Part 1: Stakeholder consultation. International Finance Corporation. PDF. https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:1e1092b2-09d5-47c1-b6bd-be2a96f46081.

Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and Internet surveys: The tailored design method (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

Driscoll, C. & Starik, M. (2004). The primordial stakeholder: Advancing the conceptual consideration of stakeholder status for the natural environment. Journal of Business Ethics, 49(1), pp. 55-73. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000013852.62017.0e

Hagan, M. (2017, August 28). Stakeholder mapping of traffic ticket system. Open Law Lab. Available: http://www.openlawlab.com/2017/08/28/stakeholder-mapping-the-traffic-ticket-system/ . CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Hopper, J. (2010). How long should a survey be? Retrieved from http://www.verstaresearch.com/blog/how-long-should-a-survey-be

Last, S. (2019). Technical writing essentials. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/

Microsoft. (2025, January 27). Drafting survey questions prompt assistance. Copilot.

Mungikar, S. (2018). Identifying stakeholders [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8uZiGB8DeJg

Neuman, W. L. (2003). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Nikki. (2004) “Wicked.” Urban Dictionary: WICKED

OHCHR. (2013). Free, prior and informed consent of

indigenous peoples. Microsoft Word – FPIC (final) Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights.

Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL). (n.d.). Creating good interview and survey questions. Purdue University. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/conducting_primary_research/interview_and_survey_questions.html

QuestionPro. (n.d.). 10 steps to a good survey design [Infographic]. Survey design. https://www.questionpro.com/features/survey-design/

United Nations. (2015). THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development

University of Victoria Campus Planning and Sustainability. (n.d.). Engagement plan for: The University of Victoria Grand Promenade landscape plan and design guidelines. Campus Greenway. University of Victoria. https://www.uvic.ca/campusplanning/current-projects/campusgreenway/index.php

University of Victoria Campus Planning and Sustainability. (2018). The Grand Promenade Design Charrette: Summary Report 11.2018,” Campus Greenway. University of Victoria. https://www.uvic.ca/campusplanning/current-projects/campusgreenway/index.php