5.1 Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion: Terminology

Introduction

Humans have always been diverse in their cultural beliefs and practices. But as new technologies have led to the perception that our world has shrunk, and demographic and political changes have brought attention to cultural differences, people communicate across cultures more now than ever before. The oceans and continents that separate us can now be traversed instantly with an e-mail, phone call, tweet, or status update. Today, our workplaces are more integrated in terms of race, sexuality, age, physical and mental ability, and gender, increasing our interaction with domestic diversity. The Disability Rights Movement and Gay Rights Movement have increased the visibility of people with disabilities and sexual minorities. But just because we are exposed to more difference doesn’t mean we understand it, can communicate across it, or appreciate it. This chapter will help you do all three by providing the terminology required to better understand and communicate issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI). Let’s begin the process with the video: What Do Equality, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Mean (2021).

It’s important to understand how EDI and communication relate. Discussing these issues is difficult for many reasons. One is due to uncertainty about language use. People may be frustrated by their perception that labels change too often or be afraid of using an “improper” term and being viewed as insensitive. It is important, however, that we not let political correctness get in the way of meaningful dialogues and learning opportunities related to difference. Exploring some of these very difficult issues can make us more competent communicators and open us up to more learning experiences.

Knowledge Check

Defining Identity

Ask yourself the question “Who am I?” Our parents, friends, teachers, and the media help shape our identities. While this happens from birth, most people reach a stage where increased social awareness led them to begin to reflect on who they are. This begins a lifelong process of thinking about who we are now, who we were before, and who we will become (Tatum, 2000). Our identities make up an important part of our self-concept and can be broken down into three main categories: personal, social, and cultural identities (see Table 5.1.1).

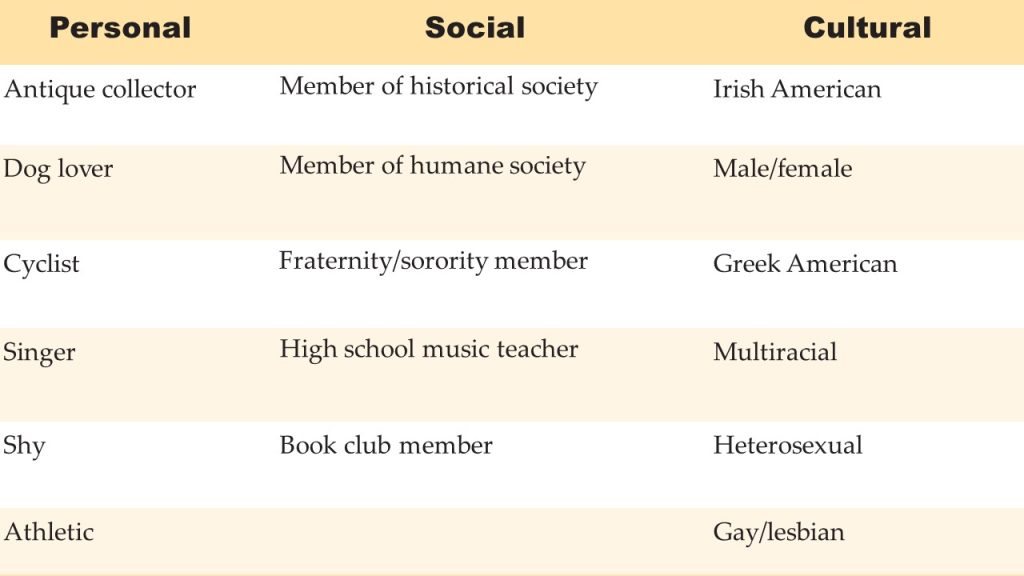

Table 5.1.1 Personal, social, and cultural identity

Personal identities include the components of self that are primarily intrapersonal and connected to our life experiences. For example, some people may consider themselves puzzle lovers, while others may identify as fans of hip-hop music.

Our social identities include components that come derived from our involvement in social groups. For example, we may get aspects of our social identity from our family or from a sports team we are part of. Social identities differ from personal identities because they are externally organized through membership. Our membership may be voluntary (Greek organization on campus) or involuntary (family) and explicit (we pay dues to our labour union) or implicit (we purchase and listen to hip-hop music). There are many options for personal and social identities. While our personal identity choices express who we are, our social identities align us with particular groups. Through our social identities, we make statements about who we are and who we are not.

Cultural identities are based on categories developed by society that teach us how to behave (Yep, 2002). Since our cultural identities are a part of us since birth, cultural identities are the least changeable of the three identities. Our cultural identities can change over time, but what separates this category from the other two categories is their historical roots (Collier, 1996).

Dominant and Non-dominant identities have been established by social and cultural influences (Allen, 2011). Dominant identities historically had and currently have more resources and influence, while non-dominant identities historically had and currently have fewer resources and influence. It’s important to remember that these distinctions are being made at the societal level, not the individual level. There are obviously exceptions, with people in groups considered non-dominant obtaining more resources and power than a person in a dominant group. However, the overall trend is that difference based on cultural groups has been institutionalized, and exceptions do not change this fact.

Because of this uneven distribution of resources and power, members of dominant groups are granted privileges while non-dominant groups are at a disadvantage. This means non-dominant groups will face various forms of institutionalized discrimination, including racism, sexism, heterosexism, and ableism. As we will discuss later, privilege and disadvantage are not “all or nothing.” No two people are completely different or completely similar, and no one person is completely privileged or completely disadvantaged.

Cultural Identities

Culture is a complicated word to define, as there are many ways that the term culture is commonly used. For the purposes of exploring the communicative aspects of culture, we will define culture as the ongoing negotiation of learned and patterned beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviours. The definition points out that culture is learned. Culture is also patterned in that there are recognizable widespread similarities among people within a cultural group. There is also deviation from and resistance to those patterns by individuals and subgroups within a culture, which is why cultural patterns change over time. Last, the definition acknowledges that culture influences our beliefs about what is true and false, our attitudes including our likes and dislikes, our values regarding what is right and wrong, and our behaviours. Some categories of culture are explored below.

Race

Race is a socially constructed category based on differences in appearance that have been used to create a social order that gives privilege to some and disadvantage to others. Race didn’t become a socially and culturally recognized marker until European colonial expansion in the 1500s. As Western Europeans travelled to parts of the world previously unknown to them and encountered people who were different from them, a classification of races began to develop that placed lighter skinned Europeans above darker skinned people. Racial distinctions have been based largely on features such as skin colour, hair texture, and body/facial features. Even though there is a consensus among experts that race is social rather than biological, we can’t deny that race still has meaning in our society and affects people as if it were “real.”

The way we communicate about race in our regular interactions has also changed, and many people are still hesitant to discuss race for fear of using “the wrong” vocabulary. Given that race is one of the first things we notice about someone, it’s important to explore how race and communication are connected (Allen, 2011).

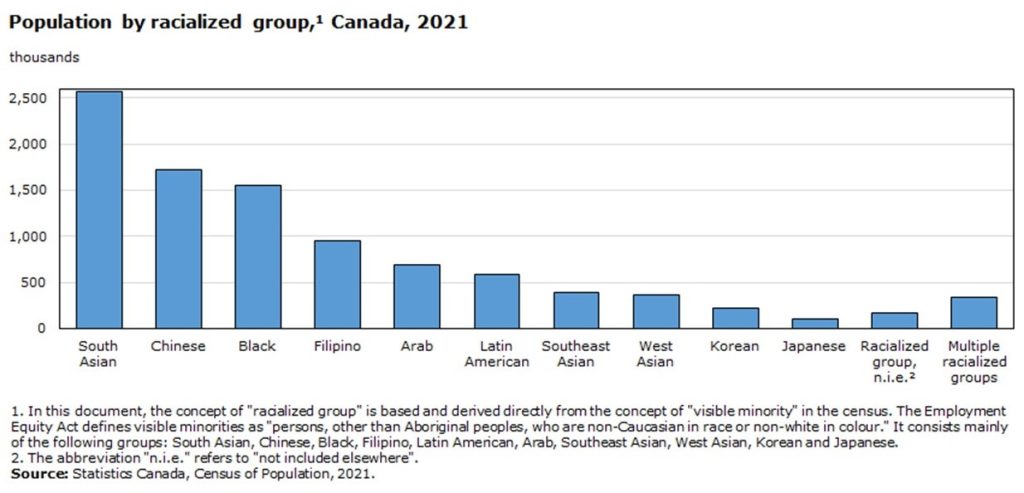

Race and communication are related in various ways. Racism influences our communication about race and is not an easy topic for most people to discuss. Today, people tend to view racism as overt acts such as calling someone a derogatory name or discriminating against someone in thought or action. However, there is a difference between racist acts and other discriminatory behaviours that are much more subtle. As competent communicators and critical thinkers, we must challenge ourselves to be aware of how racism influences our communication at individual and societal levels. Figure 5.1.1 presents a recent census on racial make-up confirming Canada’s diversity and the need to develop inter-cultural communication competency.

Gender

When we first meet a newborn baby, we ask whether it’s a boy or a girl. This question illustrates the importance of gender in organizing our social lives and our interpersonal relationships. While it is true that there are biological differences between who we label male and female, the meaning our society places on those differences is what actually matters in our day-to-day lives.

You may have noticed the word gender instead of sex is being used. That’s because gender is an identity based on internalized cultural notions of masculinity and femininity that is constructed through communication and interaction. However, sex is based on biological characteristics, including external genitalia, internal sex organs, chromosomes, and hormones (Wood, 2005). A related concept, gender roles, refers to a society’s expectations of people’s behaviour and attitudes based on whether they are females or males. Understood in this way, gender, like race, is a social construction.

Sexuality

While race and gender are two of the first things we notice about others, sexuality is often something we view as personal and private. Sexuality relates to culture and identity in important ways that extend beyond sexual orientation, just as race is more than the colour of one’s skin and gender is more than one’s biological and physiological manifestations of masculinity and femininity.

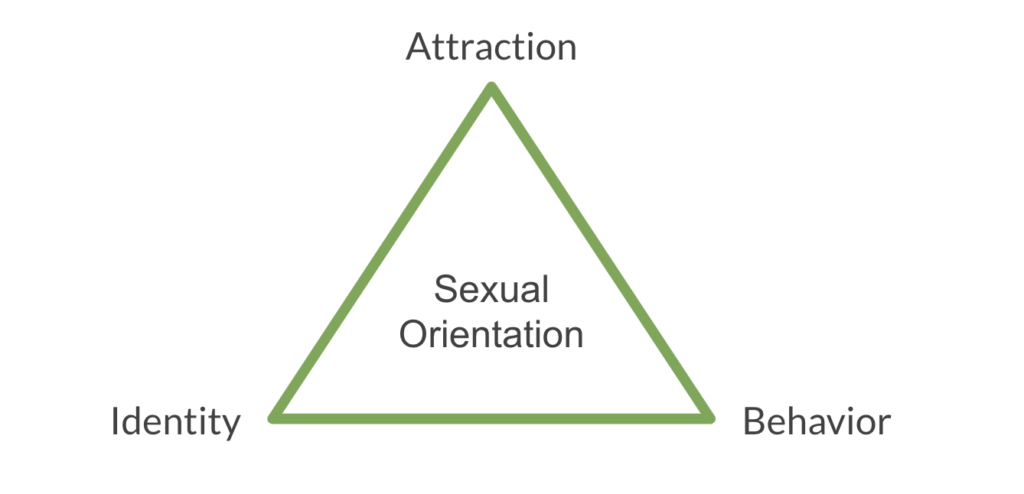

The most obvious way sexuality relates to identity is through sexual orientation. Sexual orientation refers to a person’s primary physical and emotional sexual attraction and activity. The terms we most often use to categorize sexual orientation are heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and asexual. Gays, lesbians, and bisexuals are sometimes referred to as sexual minorities.

Homophobia is a range of negative attitudes and feelings towards homosexuality or people perceived as homosexual. Homophobia is observable in critical and hostile behaviour like discrimination and violence. Much like racism or sexism, homophobia involves the targeting of a specific population of individuals with certain traits. Homophobia, or the fear of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals, is often the impetus for discrimination, which can be expressed through either institutional or informal means (“Homophobia”, 2020).

Thus, cultivating the awareness to recognize and address institutional and informal means of discrimination based on sex, gender, sexuality, and sexual orientation are important aspect of developing communication competence.

Ability

There is resistance to classifying ability as a cultural identity. While much of what distinguishes physically and mentally abled persons from physically and mentally disabled persons is rooted in science, biology, and physiology, there are important sociocultural dimensions. The Accessible Canada Act defines disability as “any impairment, including a physical, mental, intellectual, cognitive, learning, communication or sensory impairment — or a functional limitation — whether permanent, temporary or episodic in nature, or evident or not, that, in interaction with a barrier, hinders a person’s full and equal participation in society” (Minister of Justice, 2023). An impairment is defined as “any temporary or permanent loss or abnormality of a body structure or function, whether physiological or psychological” (Allen, 2011). These definitions are important because they note the social aspect of disability in that people’s life activities are limited. In addition, the definitions also suggest the social aspect of disability because the perception of a disability by others can lead someone to be classified as such. Ability, just as the other cultural identities discussed, has institutionalized privileges and disadvantages associated with it.

Ableism is the system of beliefs and practices that produces a physical and mental standard that is projected as normal for a human being and labels deviations from it abnormal, resulting in unequal treatment and access to resources. Ability privilege refers to the unearned advantages that are provided for people who fit the cognitive and physical norms (Allen, 2011). According to Figure 1.3, “in 2022, 27% of Canadians aged 15 and older, or 8 million people, had at least one disability” (StatsCan, 2023). Canadians living with a disability make up a large portion of our society. Thus, as society slowly begins to accommodate Canadians with disabilities, there is a need for inter-ability communication competence. Inter-ability communication is communication between people with differing ability levels; for example, a hearing person communicating with someone who is hearing impaired or a person who doesn’t use a wheelchair communicating with someone who uses a wheelchair.

Knowledge Check

EDI Terminology

As stated a little earlier in this chapter, conversations around EDI can be difficult, even scary, for many because no-one wants to say the wrong thing or to offend someone else. In this section, you will find a few terms that will be used throughout our discussion of EDI in this textbook; terms, that once learned, you can use to have meaningful conversations about EDI.

Microaggression

According to Kevin Nadal (2014), microaggressions are brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioural, or environmental actions (whether intentional or unintentional) that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward members of oppressed or targeted groups including: people of colour, women, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) persons, persons with disabilities, and religious minorities. Some scholars today argue that racism, sexism, homophobia, and other forms of discrimination are no longer as blatant as they may have been in the past. Instead, people may demonstrate their biases and prejudices in more subtle ways, otherwise known as microaggressions.

Microaggressions, as the following video, What is the Definition of Microaggression (2023), explains are not harmless. According to Nadal (2014), members of marginalized groups that experience microaggressions experience depression, anxiety, and trauma.

Intersectionality

The privileges-disadvantages conflict captures the complex interrelation of unearned, systemic advantages and disadvantages that operate among our various identities. As was discussed earlier, our society consists of dominant and nondominant groups. Accordingly, different cultures and identities have certain privileges and/or disadvantages.

To understand this interaction, we must view culture and identity through a lens of intersectionality, which asks us to acknowledge that we each have multiple cultures and identities that intersect with each other. Because our identities are complex, no one is completely privileged and no one is completely disadvantaged. For example, while we may think of a White, heterosexual male as being very privileged, he may also have a disability that leaves him without the able-bodied privilege that an abled body Latina woman has.

which asks us to acknowledge that we each have multiple cultures and identities that intersect with each other. Because our identities are complex, no one is completely privileged and no one is completely disadvantaged. For example, while we may think of a White, heterosexual male as being very privileged, he may also have a disability that leaves him without the able-bodied privilege that an abled body Latina woman has.

This is often a difficult discussion for students to understand, because they are quick to point out exceptions that challenge this notion. For example, many people like to point out global media personality Oprah Winfrey as a powerful African American woman. While she is definitely now quite privileged despite her disadvantaged identities (black, woman, and born poor), her trajectory isn’t the norm. When we view privilege and disadvantage at the cultural level, we cannot let individual exceptions distract from the systemic and institutionalized ways in which some people in our society are disadvantaged while others are privileged.

Systemic Racism

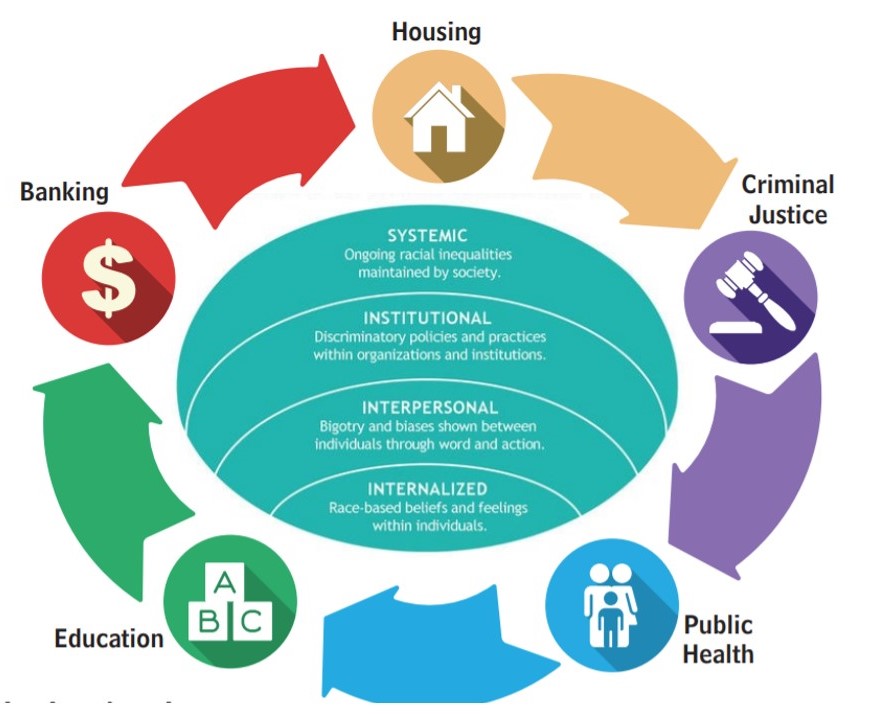

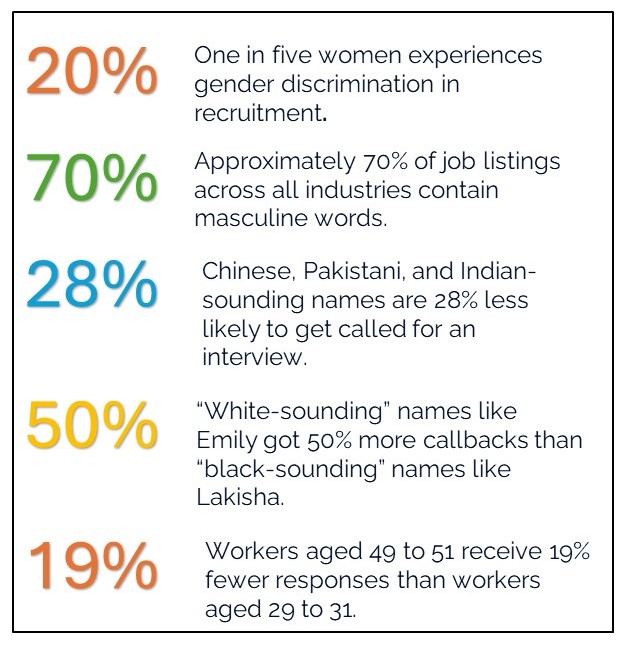

Today, people tend to view acts of exclusion and discrimination as overt acts such as calling someone a derogatory name or discriminating against someone in thought or action. However, there is a difference between these types of individual acts, and systemic racism. Systemic racism is not as easily identifiable and is not attached to a person or a singular act. Instead, systemic racism occurs through patterns, practices, behaviours and ways of being established in societal institutions, laws, and policies that favour some and disadvantage others. Thus, racism, discrimination, and acts of exclusion exists and occur daily that are not committed by any one person but occur via the practices, policies, laws, and culture that exists in our societal institutions. Figure 5.1.4 illustrates some of the societal institutions where systemic racism exists.

Techno-racism

When computer systems are created with information and algorithms that themselves contain bias, their use by commercial, educational, employment, medical, policing, and other institutions can have devastating impacts on persons of colour because of the heavy reliance of these institutions on the technology. Techno-racism is a form of racism that is embedded in the algorithms of the technology that we use daily (Nkonde in Karimi, 2021). Such bias often results, for example, in facial-recognition misidentification, mortgage algorithms errors (Karimi, 2021), as well as in voice-recognition errors. Bias is also known to be embedded in artificial intelligence systems that have been trained with data that contain bias.

Unconscious Bias

Today, there is a greater appreciation of the fact that not all biases are overt hostility based on a personal animosity toward members of a group. Unconscious bias (also called “automatic” or “implicit” biases) are unexamined and sometimes subtle behaviours and/or thoughts, but are just as real in their consequences and impacts. An unconscious bias can be considered automatic, ambiguous, and ambivalent, but it is nonetheless biased, unfair, and disrespectful to a belief in equality.

Most people have a positive view of themselves. They believe they have good values, rational thoughts, and strengths. Most people also identify as members of certain groups but not others. They are Canadian, or fans of Manchester United, or are doctors. Logic suggests, then, that because we like ourselves, we also like the groups in which we are members. We might feel affinity toward people from our home town, a connection with those who attend our university, or commiserate with the experience of people who share our gender identity, religion, or ethnicity. Liking yourself and the groups to which you belong is natural. The larger issue, however, is that own-group preference often results in liking other groups less. And whether you recognize this “favouritism” as wrong, this trade-off is relatively unintended, immediate, and irresistible.

Most people have a positive view of themselves. They believe they have good values, rational thoughts, and strengths. Most people also identify as members of certain groups but not others. They are Canadian, or fans of Manchester United, or are doctors. Logic suggests, then, that because we like ourselves, we also like the groups in which we are members. We might feel affinity toward people from our home town, a connection with those who attend our university, or commiserate with the experience of people who share our gender identity, religion, or ethnicity. Liking yourself and the groups to which you belong is natural. The larger issue, however, is that own-group preference often results in liking other groups less. And whether you recognize this “favouritism” as wrong, this trade-off is relatively unintended, immediate, and irresistible.

Social psychologists have developed several ways to measure this automatic preference, the most famous being the Implicit Association Test (IAT) which measures relatively automatic biases that favour own group relative to other groups (IAT; Greenwald, Banaji, Rudman, Farnham, Nosek, & Mellott, 2002; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998). The test itself is rather simple (and you can experience it yourself here). The IAT is an especially useful way to measure potential biases because it does not simply ask people to openly report on the extent to which they discriminate against others. Instead, it measures how quickly people make judgments about the goodness or badness of various groups. The IAT is sensitive to very slight hesitations that result from having automatic or unconscious biases.

People are generally faster at pairing their own group with “good” categories. In fact, this finding generally holds regardless of whether one’s group is measured according to race, age, religion, nationality, and even temporary, insignificant memberships.

It turns out, that people’s reaction time on the IAT predicts actual feelings about out-group members, decisions about them, and behaviour toward them, especially nonverbal behaviour (Greenwald, Poehlman, Uhlmann, & Banaji, 2009). For example, a job interviewer might have two qualified applicants; a man and a woman. Although the interviewer may not be “blatantly biased,” their “automatic or unconscious biases” may be harmful to one of the applicants. For example, the interviewer might hold a negative view of women and, without even realizing it, act distant and withdrawn while interviewing the female candidate. This sends subtle cues to the applicant that she is not being taken seriously, is not a good fit for the job, or is not likely to get hired. These small interactions can have devastating effects on the hopeful interviewee’s ability to perform well (Word, Zanna, & Cooper, 1974).

Although this is unfair, sometimes the unconscious associations—often driven by society’s stereotypes—trump our own explicit values (Devine, 1989). Sadly, this can result in consequential discrimination, such as allocating fewer resources to disliked outgroups (Rudman & Ashmore, 2009).

Ally or Allyship

Merriam-Webster defines “ally” as “one that is associated with another as a helper; a person or group that provides assistance and support in an ongoing effort, activity or struggle” (TCU, 2022, para 1). In recent years, the term has been adopted specifically to a person supporting a marginalized group. In this respect, being an ally means disrupting oppressive spaces and places. It is understanding the struggle of oppressed and marginalized people and how that oppression operates in order to end it through action. For someone in a dominant group, being an ally requires self-reflection on their own privilege as well as accepting their role in oppression.

Being or becoming an ally is a process rather than a destination; the process requires continual learning and self-awareness. Being an ally requires action: telling colleagues that their jokes are inappropriate; advocating for the health, wellness and acceptance of people from underrepresented or marginalized groups. Ultimately, an ally is someone who is willing to use their privilege as a member of a dominant group and the power that comes with that privilege to advocate and work on behalf of the interests of marginalized and oppressed groups.

Privilege

The Oxford Language dictionary defines privilege as “a special right, advantage, or immunity granted or available only to a particular person or group”. In the context of EDI, “privilege refers to the social, economic and political advantages or rights held by people from dominant groups on the basis of gender, race, sexual orientation, social class, etc. [Privilege is] unearned social power (set of advantages, entitlements, and benefits) accorded by the formal and informal institutions of society to the members of a dominant group (e.g., white/Caucasian people with respect to people of colour, men with respect to women, heterosexuals with respect to homosexuals, adults with respect to children, and rich people with respect to poor people)” (EDI Glossary, n.d.).

Privilege is often difficult to recognize for members of dominant groups because while many are willing to admit that those in marginalized groups live with a set of disadvantages, very few are willing to acknowledge the benefits they receive from being a member of the dominant group. “In other words, men are less likely to notice/acknowledge a difference in advantage because they do not live the life of a woman; white people are less likely to notice/acknowledge racism because they do not live the life of a person of colour; straight people are less likely to notice/acknowledge heterosexism because they do not live the life of a gay/lesbian/bisexual person” (EDI Glossary, n.d.). The following TedTalk video, Understanding My Privilege, explores the benefits of recognizing and unpacking privilege.

Decolonization

Colonization is not an event. It is a structure. It is not something that happened in the past. Colonization is a complex system that is currently working to negatively impact each and every one of us. Colonization has led to the environmental destruction of the land, the attack on human lives, and the economic inequities experienced predominately by racialized people. It has caused, enforced, and protected acts of slavery and genocide. It is a local phenomenon and a global phenomenon. Colonization can be found on street names that honour white colonizers, in textbooks that wipe out Indigenous history, and in the dominating European powers that have planted themselves around the world. To deconstruct colonization, we must collectively engage in a process of decolonization.

Decolonization requires a dismantling of power imbalances that uphold white superiority and dominance “and a shifting of power towards political, economic, educational, and cultural independence and power that originate from a colonized nation[‘s] own indigenous culture” (EDI Glossary, n.d.). Decolonization involves the dismantling of the social, political, and institutional structures that perpetuate systems deeming one group superior to another. Review the follow video, Decolonial Thinking, for a further explanation of what decolonization means.

Knowledge Check

Conclusion

Transformative learning takes place at the highest levels and occurs when we encounter situations that challenge our accumulated knowledge and our ability to accommodate that knowledge. Thus, developing communication competence in the area of equity, diversity, and inclusion will entail a degree of discomfort as we challenge our accumulated knowledge. Some of the skills important to developing this communication competence are the ability to empathize, accumulate cultural information, listen, resolve conflict, manage anxiety (Bennett, 2009) and to use the correct terminology to communicate our thoughts. You are already developing a foundation for these skills by reading this unit. In our next chapter, we examine EDI in the Canadian Workforce.

Attributions

This page has been edited and remixed from the following sources. Supplemental information has been provided by Tricia Hylton.

“Intercultural Communication” (2020) by Shannon Ahrndt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

“Prejudice, Discrimination, and Stereotyping” by Susan T. Fiske is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

“Skoden” Copyright © 2022 by Seneca College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Allen, B. J. (2011). Difference matters: Communicating social identity (2nd ed.). Waveland. Choice Programs. (2021). What is structural racism [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGY1EXgYD9g

CityNews. (2020). Defining systemic racism in Canada. Video. https://youtu.be/haaY5U4Tavw?si=T87Y32ueaIfsL0ns

Collier, M. J. (1996). Communication competence problematics in ethnic friendships. Communication Monographs, 63(4), 314–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759609376397

CGSMUS. (2023). Decolonial thinking [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Km_TmRuk7Q

Gory, R. (2019). The evolving terms of sexuality and romantic attraction. Dictionary.com. https://www.dictionary.com/e/sexual-and-romantic-orientation/

Equinet. (2020). The other pandemic: Systemic racism and its consequences. Standard for equality bodies. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGY1EXgYD9g

iHasco. (2021). What do equality, diversity, equity and inclusion mean? [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=St4hkzk1rdw.

Homophobia. (2020, February 20). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia. org/w/index.php?title=Homophobia&oldid=941774160

Karimi, F. (2021). Techno-racism: People of color’s new enemy | CNN

Mrkonjic, E. (2022). 21 eye-opening blind hiring statistics. GoRemotely. https://goremotely.net/blog/blind-hiring-statistics/

Ministry of Justice. (2023). Accessible Canada Act. Government of Canada. https://lawslois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/A-0.6.pdf

Nadal, K. (2014). A guide to responding to microaggression. Cuny Forum, 2(1), 71 – 76. https://ncwwi-dms.org/resourcemenu/resource-library/inclusivity-racial-equity/cultural-responsiveness/1532-a-guide-to-responding-to-microaggressions/file#:~:text=Kevin%20L.,toward%20oppressed%20or%20targeted%20groups.%E2%80%9D.

Oxford Languages. (n.d.). The oxford English dictionary. https://languages.oup.com/research/oxford-english-dictionary/

Statistics Canada. (2022). Racialized groups [Image]. Canada at a glance, 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/12-581-x/2022001/sec3-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2023). New data on disability in Canada. [infographic]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2023063-eng.htm

Tatum, B. D. (2000). The complexity of identity: “Who am I?” In M. Adams, W. J. Blumfeld, R. Casteneda, H. W. Hackman, M. L. Peters, & X. Zuniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (p. 9). Routledge.

TCU. (2022). Pride month: What does it mean to be an ally? News. https://www.tcu.edu/news/2022/what-does-it-mean-to-be-an-ally.php#:~:text=Merriam%2DWebster%20defines%20%E2%80%9Cally%E2%80%9D,person%20supporting%20a%20marginalized%20group.

Tedx Talks. (2017). Understanding my privilege [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XlRxqC0Sze4.

The Other Box: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. (2023). What is the definition of microaggression. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=19Lk9O6vMCM

Tucker, G. (2021). Measure implicit bias in your organization and eliminate it now. HRProfessional magazine. https://hrprofessionalsmagazine.com/2020/12/31/measure-implicit-bias-in-your-organization-and-eliminate-it-now/

University of British Columbia. (n.d.). EDI concepts and definitions. EDI glossary. https://vpfo.ubc.ca/edi/edi-resources/edi-glossary/#p

Wood, J. T. (2005). Gendered lives: Communication, gender, and culture (5th ed., p. 19). Thomas Wadsworth.

Yep, G. A. (2002). My three cultures: Navigating the multicultural identity landscape. In J. N. Martin, L. A. Flores, & T. K. Nakayama (Eds.), Intercultural communication: Experiences and contexts (p. 61). McGraw-Hill.

Using GenAI Tools

GenAI models have evolved considerably since their initial release and new ones as well as AI assistants are being developed on an ongoing basis in commercial and open source arenas. The capabilities are also expanding: We can now create organized systems of AI agents wherein several AI models or tools can take on specific roles then interact autonomously with each other to achieve a common goal. Regardless of the structure, good direction will result in effective outcomes.

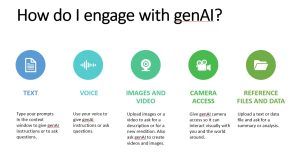

Whereas initially you had to use text to command the genAI model, now you may choose to use voice, text, images, camera, data, and PDF files in your prompting strategy, though capabilities will vary from one model to another. For example at this writing, Mistral/Mixtral offers only text-bases functions. In addition, genAI models have been trained to interact with you using a conversational approach, allowing you to engage with them in a multimodal way that is as familiar as speaking to any human.

Given the general public's lack of familiarity with the technology itself and the implications of its use on our own work, on organizations, and on society, proceeding with courage, curiosity, and caution is advisable. The following offers some general tips on how to use genAI models along with an overview of selected tools that would be useful in technical contexts.

Tips for Using GenAI

With some genAI models, you can direct the model to use a specific tone: friendly, casual, professional, technical, and the like. Selecting the tone in the features or requesting it in your prompt will affect the vocabulary, syntax, and content of the output. It will also affect the manner in which the genAI tool interacts with you. In fact, you will find that genAI tools often sound very much like humans, and can exhibit unexpected traits such as cuteness, curtness, flamboyance, and rudeness. Most times, and depending on the model, it will tend to respond in a manner in which it is prompted to respond, so the general rule for focused interaction in business contexts is to be polite and professional. Your degree of politeness is significant. Researchers have discovered that the use moderate politeness in prompting will result in better outcomes and that this approach applies to modulations for cultural contexts and different languages (Yin et al., n.d.). Besides, when using politeness, your interaction with the model will be that much more pleasant.

While you can certainly use genAI in a casual manner by simply inputting a question and seeing what comes up in the output, in the workplace we tend to have limited time, a specific purpose, and contextual information we want to see in the output, so taking a more deliberate, problem-solving approach in the use of genAI will result in usable output and time saved.

The following tips, organized according to a typical workflow, aim to help you use genAI models in your day-to-day professional tasks such as email, report, and presentation drafting. Be sure to work within the requirements and constraints of the organization you are representing. Remember that you should always consider genAI outputs as draft material to be revised and supplemented and that you should always declare your use of genAI content. Doing so will sustain your credibility as a reliable communicator.

Before Beginning

Conversational prompting is the most effective way to draft typical workplace documents including summaries, routine correspondence, reports, and presentations. Assessing your goals and situational needs and constraints will help you develop a game plan for using the genAI tools to advantage. The amount of preparation will be determined by how complex your request and expected output will be. Of course, in situations requiring only brief one-time interactions for simple tasks, not so much planning would be required.

- Consider your audience’s needs and the context: Completing thorough audience and context analyses before beginning will help you to narrow the focus of your work, address the needs of the audience, and adapt your communication strategy to the situation at hand.

- Identify your objectives: Clearly articulate your goal, and reflect on how the genAI model can assist you in achieving it. For example, your objective may be to write a proposal for conducting a fire safety inspection at a manufacturing plant. To narrow your focus on the objective, ask yourself: Are you responding to a request, analyzing data, addressing an opportunity or problem? Are you creating a proposal, sending correspondence, creating a presentation or video? It might help at this stage to think of achieving your goal in a step by step manner in order to plan an efficient research, drafting, and revision strategy and determine how the model can assist at each stage.

- Determine the types of output you are seeking: Tell the genAI tool what you expect it to produce: "Draft an outline for a proposal for the fire safety inspection to be conducted at a boot manufacturing plant." Ask yourself: Are you requesting a document outline, a summary, a draft video or presentation, ideas for a topic, or a chart or graph that illustrates a point?

- Gather existing information and data: Collect the information and data you will be using to create the prompts. You will use whatever information you have available to guide the genAI model in focused tasks. Right now in most workplaces this is still done manually, but the process will soon be automated. Other ways of using existing documents is to upload PDF versions of them to the genAI tool, then providing instructions on how you want that document to be processed: summarized, analyzed, or otherwise used in the development of output.

- Select the GenAI application: Choose the genAI model that will best achieve your goal by considering the following factors: degree of reliability, cost, in-application tools, accessibility, and privacy policy. Many organizations will provide you with approved tools, so your choice of models will be limited to what is available. At Seneca, Copilot (connected to ChatGPT 4 and the internet) is available through Seneca accounts. In other contexts, you have great latitude in the choice of tools to use: open source or commercial, by subscription or free, by version, and you can choose based on capacity, features, ethical practices, capability, and the like.

- Align with your organization's policies: Review your organization’s privacy, confidentiality, and other applicable policies, so you can work within its legal and ethical standards when using genAI applications and their output.

When Using GenAI

Once you have a plan, you can more efficiently develop a strategy for prompting the genAI model to offer the output that will align with your purpose.

- Develop a prompting strategy: Review prompting techniques (see the GenAI Prompting chapter). Does the task at hand lend to conversational or a more complex structured prompting? Choose the method that will best help to achieve your goal. Doing so will reduce the amount of time and the number of iterations required.

- Consider whether to use an "all in" or a phased approach: You may want to try inputting a prompt that encompasses the entire task (one-shot), or you may choose a phased strategy (chain of thought) that involves breaking up the task into sequential stages. Again, think of what you want to achieve and decide on the best approach.

- Craft specific prompts: The more specific the prompts, the more likely the genAI model will provide outputs that match your needs. Use your planning data and information to create prompts that contain information about context, problem or need, criteria, goal, etc. The more information you provide regarding context and topic, the more useful the output.

- Treat prompting as an iterative process: Review the outputs and refine your prompts to achieve more precise, goal-oriented responses. The first output is usually not the best, so engage with the application in a conversational manner and ask it to refocus its work using additional information. If the genAI tool does not provide you with the necessary output, consider using a different model.

Reviewing the Output

Reviewing the content created by the genAI application is a critical step in ensuring that what you include in your final document is accurate, whole, and reflecting of your own and your organization's values. While genAI tools offer many advantages, their known hallucinations and lack of verifiable citations can make your final document questionable. When your reputation is on the line, opt for a careful review of the work you submit.

Use this method to compete a scaffolded review of all genAI output before you make use of it in your communications:

- Corroborate the claims: Regardless of variations in conventions of use, you must be vigilant when reviewing genAI output. Some genAI models do not include citations, so you must check or corroborate all assertions or claims, complete the research to confirm claims, revise arguments, and add the citations when they have not been included. Other models like MS Copilot will include citations; however, the content of the output may be copied in whole or in part from a source or the citation may be altogether incorrect or incomplete. Remember, most readers are interested in your ideas not those of a bot, so avoid including large swaths of genAI content in your documents.You may find Mike Caulfield's SIFT model shown in Figure 2.4.2 helpful in conducting your review.

The Four Moves of the SIFT Model--In brief and adapted for GenAI output

- Stop: Take a moment to glance through the genAI output to highlight claims that are and are not documented.

- Investigate the source: For claims that have not been documented, complete the research to verify the information and document the source. For claims that have citations, check the source material. Has the claim been copied with or without quotations? Ensure the citations are accurate.

- Find better coverage: If the claim does not accurately represent the idea you want to convey, search for a better source.

- Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original content: Ensure that the claim or quote is not taken out of context by going to the original source to understand the original context of use.

- Review the output: Remember that you are responsible for all genAI-produced content that you include in your communications. Ensure that the output you include in your documents reflect the values of the organization you serve:

- Accuracy and relevance: Determine if the output aligns with your intended purpose and if the information is accurate. Some parts of the output may be on track, while others not so much so. Use a discerning eye to review all content. Note that genAI is known to “hallucinate” or make up information, so be sure to also complete an accuracy check.

- Bias: GenAI models sometimes create outputs that contain bias related to race, religion, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and gender. Biased assumptions are harmful to people and may be damaging to the company’s and your own reputation. Responsible use of genAI involves ensuring that the content that you use is inclusive.

- Sustainability principles: Companies recognize the importance of responding to issues such as climate change, global developments, income disparities, unemployment, and indigenous inequities. Ensure that the genAI output you use aligns with the organization’s sustainability policies and practices.

- Engage with the content: Most readers will be able to distinguish between an authentic voice (your own) and the disembodied voice of a genAI model. Which would you rather be reading? Unfortunately, recent research (Dell'Acqua et al., 2023; Dell'Acqua, n.d.; Mollick, 2024) has revealed that in hybrid genAI/human collaboration, humans tend to disengage from the work and settle for outputs that are only just good enough without striving to improve on the output. Use genAI output as the basis for your own creation, and don't settle until you have achieved authenticity, precision, completeness, and excellence. Incorporate information based on your own expertise, and edit for style and tone so that the genAI content you use reflects your own uniqueness. Remember genAI is intended to augment your own knowledge and skills rather than to replace them.

- Document and declare your use of genAI: Remember that ethical citation/declaration and documentation standards must be applied to all work that you produce—with or without the assistance of genAI. At Seneca, you are required to quote or declare genAI output. Check with your professors regarding their expectations. And you may wish to consult Seneca's Guide on Citing and Documentation: Artificial Intelligence for specific detail on citation practices approved by the institution for documents you create for course related work.

In most technical contexts, a declaration of use (model, mode, usage, date) would suffice. When in the workplace, do the following:

-

- Check on genAI declarations practices with the ethics officer or your immediate supervisor to learn about the genAI policies and practices there.

- Keep records of the prompts and outputs you have used to prepare your content.

- Recognize that you are responsible for the genAI output that you use in your technical documents, correspondence, presentations, meetings, and so forth.

- Let your audience know how you have used genAI; doing so will help to sustain trust with your audience. See the GenAI Use section below for an example.

Choosing GenAI Tools

A good place to start when choosing which genAI tools to use is to ask yourself the following questions:

- What am I trying to create: images, document, music, code, presentation, video?

- What do I want the genAI tool to do for me: summarize, outline, code, research?

- What is the outcome that I want to achieve? Here, consider the degree of precision, accuracy, agility, resolution, reliability, etc. in the output you need as the different tools exhibit varying degrees of performance.

List of Selected Tools

Many thousands of AI applications are available. The following is a list of selected genAI applications depicting examples of the types that can be used for technical communication purposes. These tools offer features that will help you to create content and documents, draft code, summarize documents, create presentations and videos, conduct research, create customized images, and work in multimodal ways in office productivity platforms.

Note: At the time of writing, many items in the following list have not been approved by Seneca and are to be used only with your personal login credentials and at your own risk and responsibility. Seneca encourages you to make use of the approved Microsoft Copilot for academic purposes. Please see Seneca's Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) Policy for more information.

Chatbots (Multipurpose Content Generators)

- BingChat, ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini (formerly Bard), HuggingChat, Llama3, Mistral/Mixtral: Each of these applications are conversational agents that will create outputs based on prompts given. They each offer various features and capabilities. Their capabilities generally include content creation, summarization, and image generation through text and/or voice prompting. Content created will display varying degrees of accuracy and precision, so the outputs are always considered draft material.

Coding Applications

- Advanced Data Analysis (formerly Code Interpreter): This OpenAI application will allow you to write and run Python code. It is also used to analyze large data sets.

- Code Whisperer: Code Whisperer is Amazon's code generator that suggests code in real time.

- Github Copilot: Github Copilot suggests code and functions in real time based on context in comments and previous code.

- Tabnine: Similar to Github Copilot, with a few differences including the claim to only train the models on open source code with licenses that permit such use.

Document Formatting

- Canva: Canva offers templates for any number of communications including documents, presentations, infographics, cards, social media posts, banners, etc. With Magic Writer, the composition task is initiated but must be followed up with editing.

- Gamma: Gamma features beautiful formatting for documents, presentations, and webpages.

Productivity

- MS Copilot: Using a knowledge graph that can access various documents and tools in the enterprise version of Microsoft, this tool can summarize meeting notes, help you draft documents, draw from various documents to create content, and offer other prompt-based services. Copilot is available on Microsoft Office 365 with a purchased license and is also available for individual use for free or by subscription for the Pro version. Access to full capabilities is dependent on the administrator release of functions.

- Notion.so: An all-in-one productivity platform, with Notion.so you can write, collaborate, and plan projects using AI-powered technology.

- Otter.ai: Otter is a meeting assistant, which can join, transcribe, summarize, and record meetings. It's a great example of the types of meeting assistants now available.

Research

- Consensus: This AI search engine quickly goes through published research papers to find information based on your search parameters. Citations are provided.

- Elicit: Elicit searches through papers and citations and extracts and synthesizes key information according to your specified research focus. Best for scientific research.

- Perplexity: Perplexity is a search engine employing user-selected All Web, Academic, Reddit, YouTube, and Wolfram Alpha as databases. It also offers writing capabilities without accessing the internet.

- Research Rabbit: Research Rabbit is a citation-based mapping tool that focuses on the relationships between research works. It uses visualizations to help researchers find similar papers and other researchers in their field.

Image Generation

- Adobe Firefly: Firefly is an Adobe product that generates images based on a text prompt. Its filters allow you to quickly and intuitively modify the initial image (e.g., re-creating the same image in a different style). It’s currently free to use, but requires you to create an account and sign in.

- DALL-E 3:DALL-E is OpenAI' s image generation tool. DALL-E 3 will generate realistic images using voice and text prompting and includes inpainting (adding image elements), outpainting (removing image elements), and variations.

- Stable Diffusion: Stable Diffusion is a deep learning, text-to-image model released in 2022 based on diffusion techniques. It is primarily used to generate detailed images conditioned on text descriptions, though it can also be applied to other tasks such as inpainting, outpainting, and generating image-to-image translations guided by a text prompt.

Presentations

- Canva: Select the Presentations feature and use Magic Design to help you develop the content for your presentation in minutes.

- SlideGPT. SlideGPT is free to use to create presentations. Once the presentation has been generated you can download it as a Power Point file for a small fee.

- Tome: Tome generates presentations in minutes based on text provided or even a short prompt, complete with AI-generated images.

Video Creation

- Canva: Canva offers video creation tools that are powered by AI. Features include content and image commands that are created through Magic Media. This tool also includes talking heads.

- Sora: Released by OpenAI, Sora enables users to create realistic, near true-to-life videos using text commands.

Futurepedia is a good compendium site where you can search for free and premium genAI tools according to your specified purpose.

Attributions

Content for the section on genAI tools has been partially adapted and updated from:

Center for Faculty Development and Teaching Innovation. (2023). GenAI Tools – Generative Artificial Intelligence in Teaching and Learning (pressbooks.pub) Centennial College. CC by 4.0.

University of British Columbia (UBC). AI Tools. Tools - AI In Teaching and Learning (ubc.ca) CC by 4.0.

University of Georgetown. Artificial Intelligence Tools - cndls website (georgetown.edu)\ CC by 4.0

GenAI Use

Copilot with Bing (Creative Mode) was used by Robin L. Potter to ideate content for the section on Tips for Using GenAI using the following prompt: "Draft a set of tips for business professionals on the use of generative AI; include the following sections: Before You Begin; When Using GenAI; Reviewing the Output." Related references have been included in the list below.

References

Adobe Experience Cloud Team. (2023, August 25). 5 tips for getting started with generative AI for your business (adobe.com)

Amazon. What is CodeWhisperer? - CodeWhisperer (amazon.com)

Caulfield, M. (2019, June 19). SIFT (The Four Moves) – Hapgood

Copilot. (2024, January 16). Used in ideation for the section on Tips for Using GenAI. Microsoft.

Dell'Acqua, F. (n.d.) Falling asleep at the wheel: Human/AI collaboration in a field experiment on HR recruiters. Falling+Asleep+at+the+Wheel+-+Fabrizio+DellAcqua.pdf (squarespace.com)

Dell'Acqua, F., McFowland III, E., Mollick, E., Lifshitz-Assaf, H., Kellogg, K.C., Rajendran, S., Krayer, L., Candelon, F., and Lakhani, K.R. (2023, September 15). Navigating the jagged technological frontier: Field experimental evidence of the effects of AI on knowledge worker productivity and quality. Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper No. 24-013, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4573321 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4573321

Futurepedia - Find The Best AI Tools & Software

Gaurav, A. (2023, June 3). 13 Best FREE AI Productivity Tools 2023 | 𝐀𝐈 𝐦𝐨𝐧𝐤𝐬.𝐢𝐨 (medium.com)

Gartner. Generative AI: What Is It, Tools, Models, Applications and Use Cases (gartner.com)

Google. Gemini. Gemini - Google DeepMind

Mollick, E. (2024, January 17). LinkedIn post on "falling asleep at the wheel." Ethan Mollick on LinkedIn: A fundamental mistake I see people building AI information retrieval…

Potter, R. L. (2024). CRED: Reviewing GenAI output: Infographic.

University of Michigan (UMich). AI Tools | U-M Generative AI (umich.edu)

Wattanajantra, A. (2023, July 20). Generative AI in 7 easy steps: A practical business guide - Sage Advice Canada English

Yin, Z., Wang, H., Horio, K., Kawahara, D., and Sekine, S. (n.d.). Should we respect LLMs? A cross-lingual study on

the influence of prompt politeness on LLM performance.

2402.14531.pdf (arxiv.org) Via Ethan Mollick, LinkedIn, March 2024, Ethan Mollick on LinkedIn: Here’s an initial answer to the question I get asked most about prompting:… | 69 comments