4. Project Initiation

4.1 Statement of Project Justification

All projects are created for a reason. Often, the pressure to produce results encourages people to identify possible solutions without fully understanding the needs and purposes of the project. This approach can create a lot of immediate activity, but it also creates the likelihood that the change initiative will fail to deliver the proposed organizational value.

Miscommunication is a common occurrence in our everyday lives. Even something as simple as ordering food can lead to misunderstandings. For instance, a waiter brings us our dinner and we note that the baked potato is filled with sour cream, even though we expressly requested no sour cream. Misunderstandings are not intentional; they simply speak to the challenges associated with effective communication.

One of the best ways to gain approval for a project is to clearly communicate the project’s objectives and describe how the project provides a solution for an organizational need or opportunity. A needs analysis is often conducted to better understand the underlying organizational needs and how meeting these needs would help the organization increase its success. Once alternative solutions are identified, each is assessed to determine if it supports the organization’s vision and strategies. Issues of justification (“should we do the project?”) and feasibility (“can we do the project?”) are addressed. A final recommendation is determined after all solutions and issues are assessed. It is important to note that project justification is a key part of the project initiation phase. If issues of justification are not adequately addressed, the project will lack the required organizational support and, therefore, will ultimately be unsuccessful. An effective project justification document contains the following:

- A detailed description of the problem or opportunity with headings such as introduction, business objectives, problem/opportunity statement, assumptions, and constraints

- A list of the alternative solutions available

- An analysis of the business benefits, costs, risks, and issues

- A description of the preferred solution (if possible)

- Main project requirements

- A summarized plan for implementation that includes a schedule and financial analysis

In low complexity projects, this document may be a few pages in length. In higher complexity projects, this document may be 10 or more pages long and referred to as a business case. Regardless of the format, the project sponsor must approve the project justification document. Project justification and feasibility analyses are most effective when they are performed jointly by the functional managers who will maintain a project’s solution post-launch and the project team members who will perform the work. Realism is introduced when both parties are involved upfront in the project selection process. In addition, this collaborative process assures some level of commitment on all sides which may enhance accountability among team members. Lastly, it may become apparent that the project is not worth pursuing at any stage in the justification process. If this is the case, the project is terminated; thus, the next phase never begins. In situations where sponsor approval does occur, the required funding to proceed is provided.

It is important to note that not all projects proceed with a clear view of the solution in mind. Solutions can be created in an iterative or incremental fashion by using an adaptive development methodology. In these cases, it is important to understand what the project is striving to achieve in terms of value for the organization as this will shape the development efforts.

Often, the project leader is part of the project justification work. If not, a project leader is appointed shortly after this work has been completed. The project leader then begins to develop the project infrastructure to support all the activities associated with planning, executing, monitoring, and closing the project. The project leader conducts one or more kickoff meetings to align all the various stakeholders. The strength of the initial alignment will have a big impact on project success. At this early stage, the project leader is learning to identify the appropriate means of communicating with key stakeholders. Effective communication with project stakeholders is another critical success factor so this work must begin early.

Team building begins and collaborative approaches for working together are discussed. During these meetings, the project leader will share:

- The project’s objectives

- Known priorities and success measures

- Organizational constraints and related trade-offs

- A high-level description of the project scope

- Key milestones

- An initial list of project risks

- Key stakeholders

This information and the decisions that go along with it are often captured in a document referred to as a project charter. Just like with project justification documents, low complexity projects may have very short project charters while higher complexity projects may require longer, more comprehensive project charters. In either case, there are two very important aspects of the project charter: key stakeholders, who specifically detail their respective roles and responsibilities, and project success measures.

Similar to the project justification document, the project charter must also be approved by the project sponsor. This document formally recognizes the existence of the project by presenting the project leader’s understanding and conceptualization of the project’s objectives. Most importantly, it authorizes the project leader to apply organizational resources in order to achieve the project’s objectives. Once it is approved and formally signed off, it becomes an agreement between the project leader and the project sponsor. As such, some organizations prefer to refer to this document as a letter of agreement instead of a project charter. The title and form of the document are not important. Approval of this document, whether a letter of agreement or a project charter, signals the transition into the planning phase of the project.

4.2 Assessing Organizational Constraints and Trade-Offs

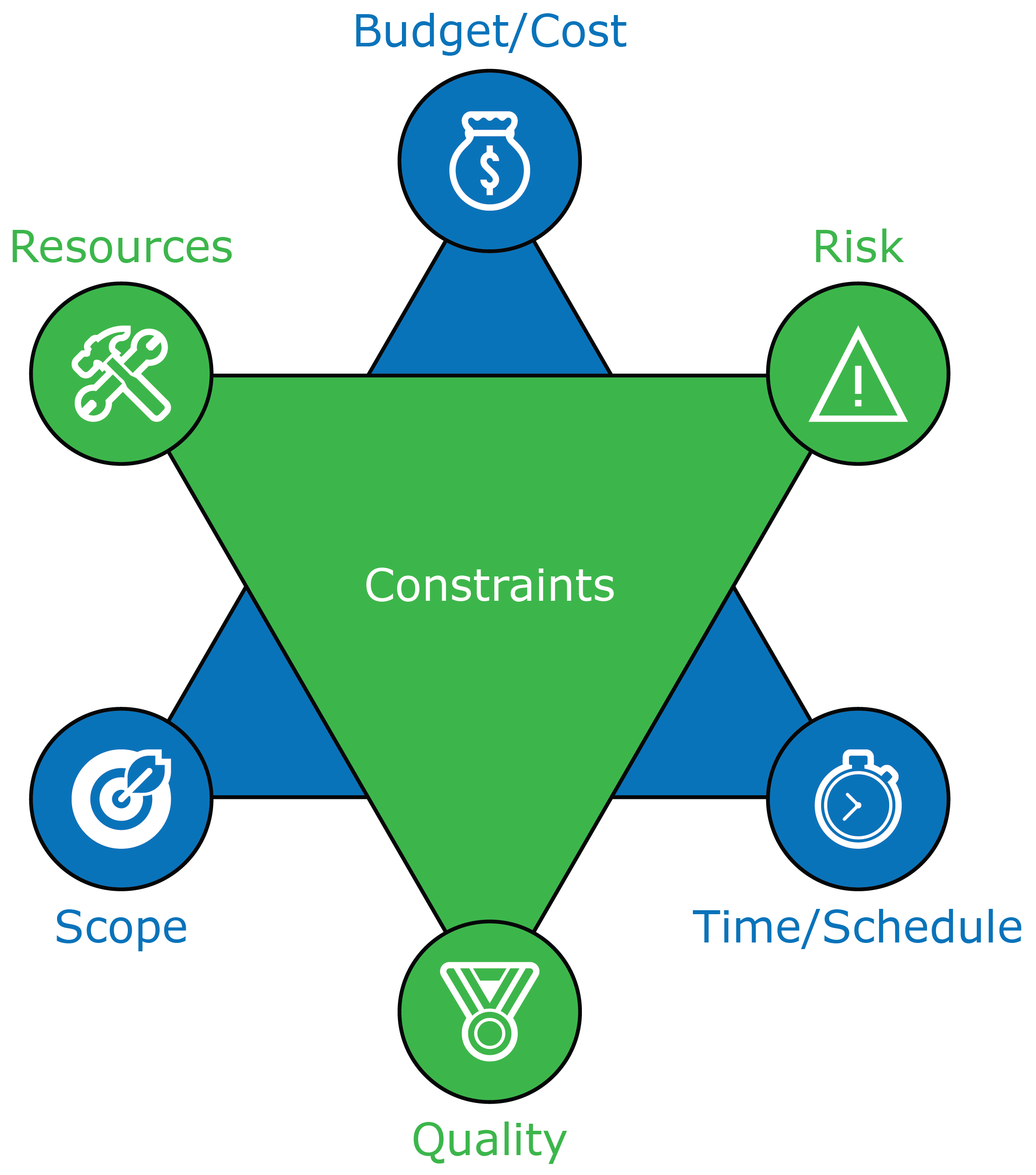

Projects have unique constraints which are often defined by the organizational objectives that drive the change. The interdependency of scope, time, and cost and the related implications for quality is of primary interest. Many project leaders refer to this as the triple constraints. Organizations face limitations that are often most apparent in the amount of work (scope), the amount of time available, and the required costs.

Exhibit 4.1: In this diagram, each circle represents one of the constraints wherein any changes to one of the constraints can cause a change to one or more constraints.

- Scope encompasses the work involved in delivering on the project’s objectives and the processes used to complete the work.

- Schedule encompasses the time available to complete the project.

- Cost encompasses the amount of money available to complete the project and includes support for the resources, supplies, and other materials required to produce the project outcomes.

- Quality encompasses the standards and criteria the project’s deliverables must meet in order for them to perform effectively. The end outcomes must meet stakeholders’ expectations and performance requirements, and service levels, such as availability, reliability, and maintainability, as well as deliver on its anticipated organizational benefits/value.

Project management has many practical applications for everyday life and a great way to highlight this is to look at the triple constraints for planning a vacation. Unfortunately, it is very unlikely that we can spend as much money as we want, stay for as long as we want, and travel any place we want. We must decide what our priorities are. If we treat the budget (cost) as our priority, it will have implications for how long we can stay (schedule) as well as the nature (scope) and overall quality of the accommodations, flight, and/or food we select.

In this example, we achieve our budget objective (fixed at $2,000) by making trade-offs with our vacation schedule and the destination (scope). If your circumstances change and you happen to have more money available for your vacation, you can evaluate the implications this has on the other constraints. For instance, you may choose to stay longer (modify your schedule), book more day trips throughout your stay (modify your scope) and/or select a hotel with more amenities (modify the quality). The opposite could be true as well. If you discover that the cost of the flight has just gone up, you would have to identify ways to reduce the costs associated with other aspects of your vacation. You could decide to shorten your stay (reduce your schedule), eliminate some of your day trips (cut scope), and/or select a hotel with fewer amenities (reduce quality).

In organizations, the circumstances surrounding project delivery may also change. For instance, if your project sponsor requests more features/functionality in the product, service, or result delivered by the project (scope modification), this may require more money and/or more time. The decisions we make about the triple constraints have broader implications. We need to consider the resource requirements and the uncertainties (risks) associated with our plans to achieve the project outcomes.

These examples effectively highlight the interdependencies between cost, schedule, and scope, and their implications on quality. It all starts with understanding the organization’s priorities. This gives the project leader and development teams the guidance needed to make effective recommendations and decisions.

4.3 Stakeholder Identification and Management

A project is successful when it achieves its objectives. The objectives need to be clear, measurable statements of organizational value. Ultimately, a project’s stakeholders will determine if the expected value was delivered.

Stakeholders are individuals who are impacted by the project or who are impacting the project. They are the people who are actively involved in carrying out the work of the project and/or have something to either gain or lose as a result of the project. The project sponsor is typically the most powerful stakeholder. They often initiate the project and as such, are often referred to as the “initiating sponsor.” They have the authority to start and stop the project and will support the achievement of project objectives by removing the barriers to success. They can be regarded as the “external champion” because they often serve as the last escalation point when the project team needs support bringing an off-track project back on track. Successful project teams know how to leverage the power and position of the project sponsor and will proactively ask them to deliver influencing communications throughout the organization in order to maintain the project’s momentum and high morale within the team. Many project sponsors assign one or more sustaining sponsors to act as the “internal champion(s)” of the project. The sustaining sponsors are often leaders of the internal departments that are most affected by the project, such as a marketing manager or human resources manager. When the project sponsor selects the sustaining sponsor(s), one of their goals is to ensure that the project team frequently considers the organizational impacts of the changes being introduced. By keeping the sustaining sponsor(s) actively engaged in the project, they will ensure their teams are intently participating in the project and identifying the operational impacts that must be considered in order for the change to be sustained once the project has been completed. On a day-to-day basis, the sustaining sponsor(s) act as the first point of escalation as issues/risks are raised.

A successful project leader will identify all stakeholders. The project sponsor and the sustaining sponsor(s) are very helpful in identifying additional project stakeholders and often consulted early in the project. Depending on the nature of the project, departments such as information technology, human resources, finance & accounting, engineering, manufacturing, and marketing are also considered to be project stakeholders. In addition, external stakeholders often include customers, suppliers, and regulatory bodies. During project initiation, it is important to effectively identify a comprehensive list of project stakeholders. This will allow the needs of these stakeholders to be identified and considered throughout the project. The stakeholders are then included in the project charter which must be approved by the project sponsor before the planning phase can begin.

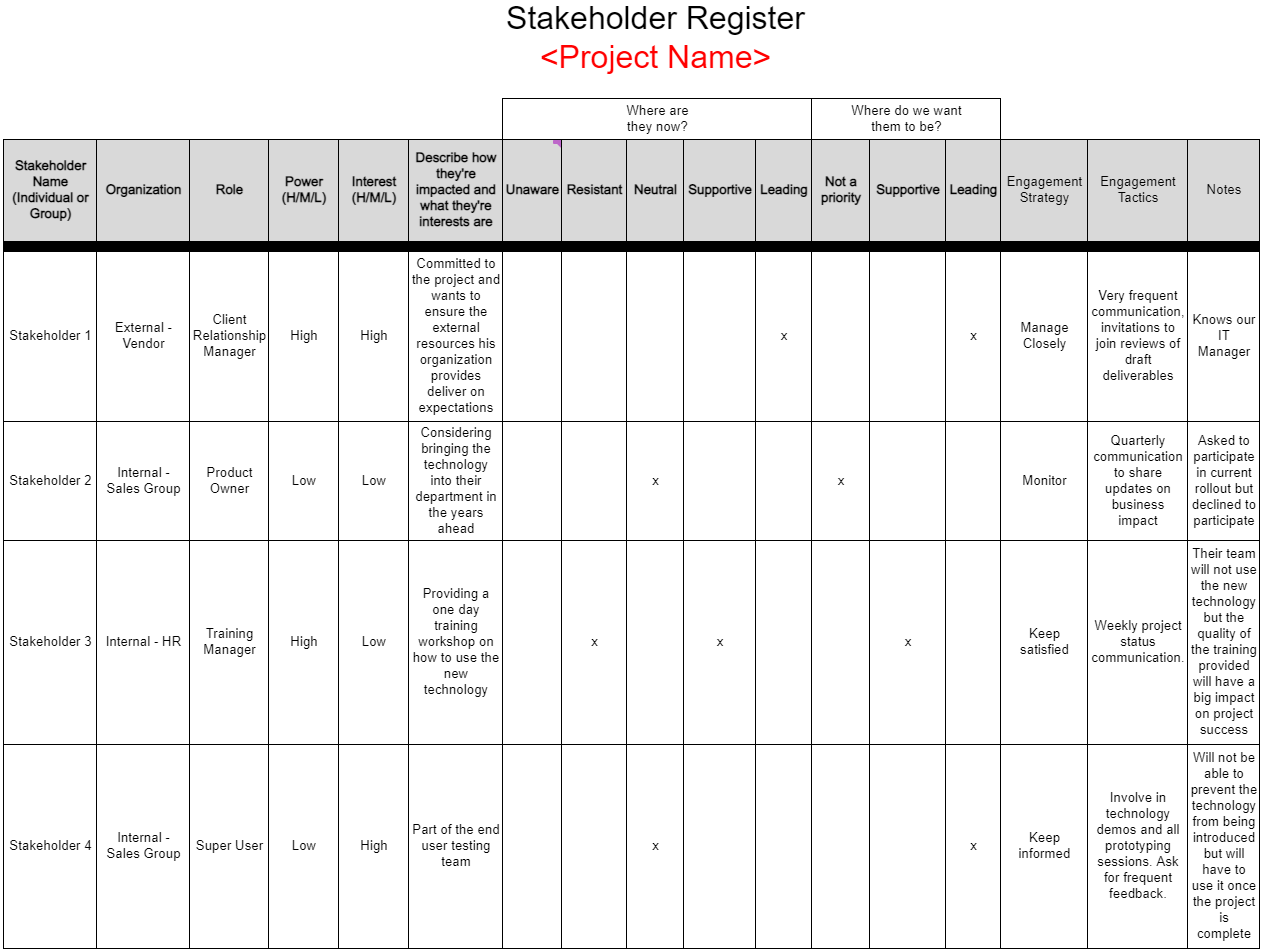

For high complexity projects, it may often be challenging to maintain an accurate picture of all the stakeholders. New stakeholders can arise at any time, and the needs and interest levels of a particular stakeholder may change through the course of the project. A stakeholder register is a powerful tool and it is specifically designed to assist in stakeholder management.

Exhibit 4.2: Example of a stakeholder register. (accessible version)

In addition, it is important to prioritize stakeholders. Some stakeholders have little interest and little influence in a project and as a result, do not require as much contact from the project team. Understanding who these stakeholders are allows the project team to spend more time with the stakeholders that have a significant interest in the project and who exert significant influence over the project. Project teams assess the interest and power/influence of project stakeholders by researching their position, their actions in previous change initiatives, and by directly speaking with them about the project. Let us delve into how the assessment is done.

When considering a stakeholder’s interest, assess the following:

- How is their performance evaluated?

- Will their performance be impacted by the project and/or the project’s outcomes?

- Are they (or individuals on their team) needed to help produce the project’s outcomes?

When considering a stakeholder’s influence/power, assess the following:

- What position do they currently hold in the organization?

- How much authority does this position afford them over the project?

- Do they have influence over people in positions of high power?

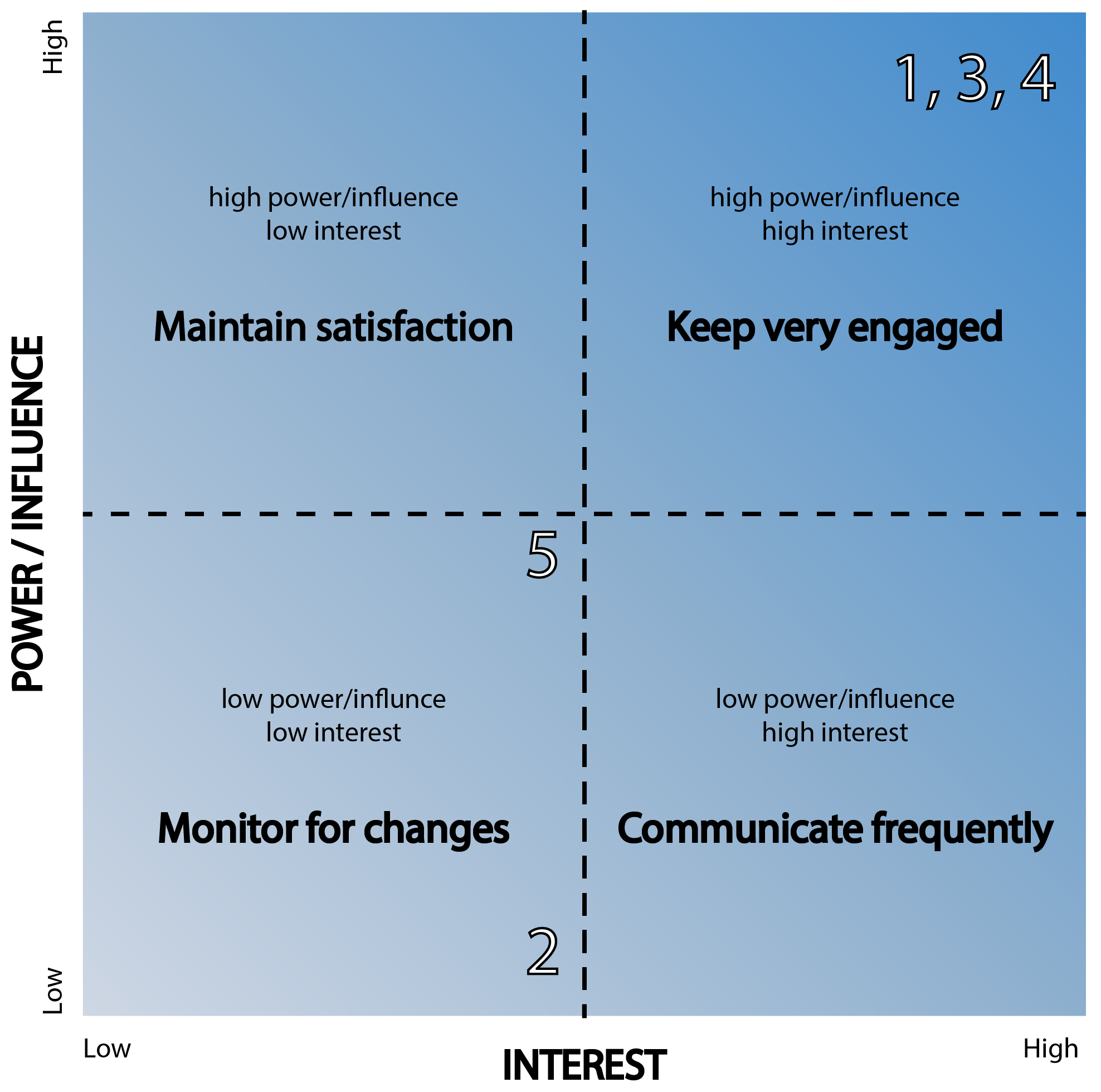

After the initial assessment has been completed, stakeholder prioritization can occur. A power/interest grid is a very helpful tool for prioritization. It helps project leaders categorize stakeholders and create effective communication strategies for each category of stakeholder on the project.

Thinking back to our vacation project, the following individuals could be our stakeholders:

- Spouse (assuming they join you)

- High interest

- High influence/power

- Neighbour (volunteered to watch over your house)

- Medium interest

- Low influence/power

- Airline company (a vendor; critical in helping you reach your destination)

- High interest

- High influence/power

- Hotel (a vendor; critical in achieving your quality expectations)

- High interest

- High influence/power

- Insurance company (a vendor; critical in providing peace of mind for travel-related risks)

- Medium interest

- Medium influence/power

As Exhibit 4.3 depicts, prioritizing our stakeholders helps us ensure we develop appropriate stakeholder management strategies.

Exhibit 4.3: The five stakeholders in the example above superposed on a power/influence and interest matrix.

Project leaders need strong soft skills to carry out this work effectively. Project leaders generally have little or no direct authority over any of these individuals, making stakeholder management particularly challenging.

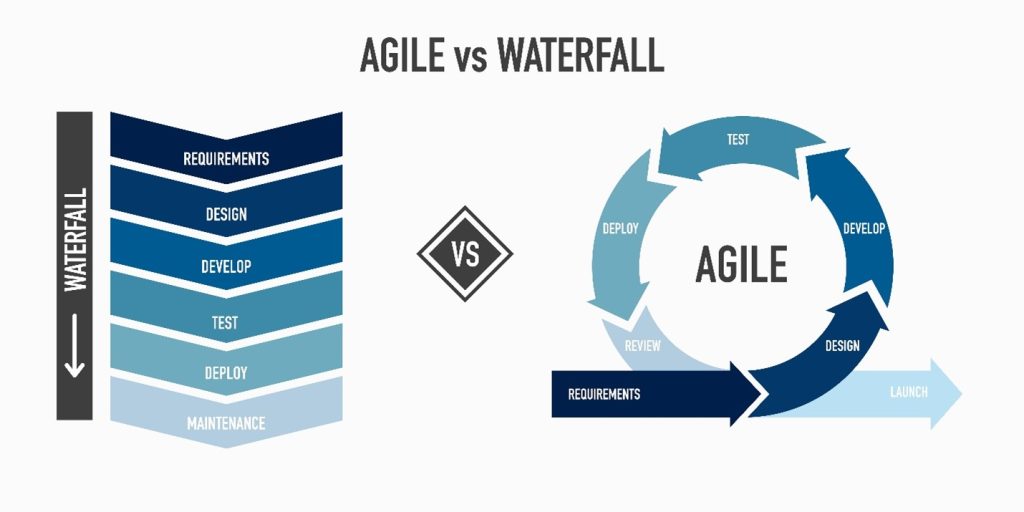

4.4 Selecting the Right Development Methodology

Determining which development methodology to use is one of the key decisions project leaders must make. Well defined projects that involve a clear vision of the solution and stakeholder requirements are well suited to the waterfall (predictive) methodology. Note: for the purposes of this text, we will consider the terms “predictive” and “waterfall” as interchangeable. Since the requirements are known and can be well defined, it is possible to design the solution in its entirety, upfront. In situations where the requirements can not be well defined upfront, project teams need an approach well suited to dynamic and evolving requirements. These projects are well suited to an agile development approach that is incremental or iterative (adaptive). Predictive and adaptive development methodologies are very different.

Exhibit 4.4: The lifecycle of Waterfall vs Agile (Source: Adobe Stock Image)

Exhibit 4.4: The lifecycle of Waterfall vs Agile (Source: Adobe Stock Image)

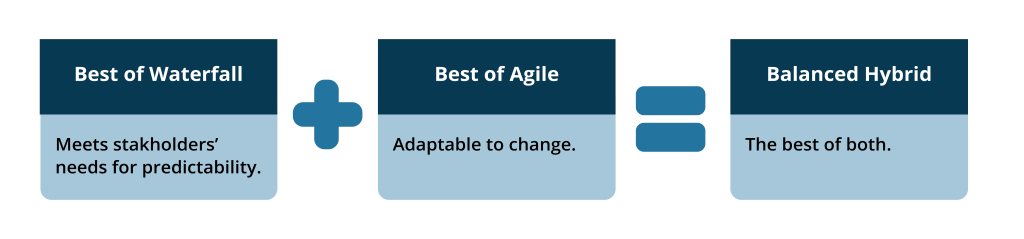

In a growing number of projects, a combination of the waterfall and agile approaches is most appropriate. In these situations, some aspects of the solution are well-defined while other aspects remain unclear. Moreover, stakeholders may expect the project team to balance outcome predictability with solution design flexibility. These needs lead to the use of a hybrid methodology.

In selecting a development methodology, it is important for project leaders to understand their stakeholders’ needs and clearly communicate why they choose the selected methodology. Communicating how the work will be managed using the selected approach will help set the team up for success.

Let’s examine each of the methodologies in more detail:

Waterfall (predictive)

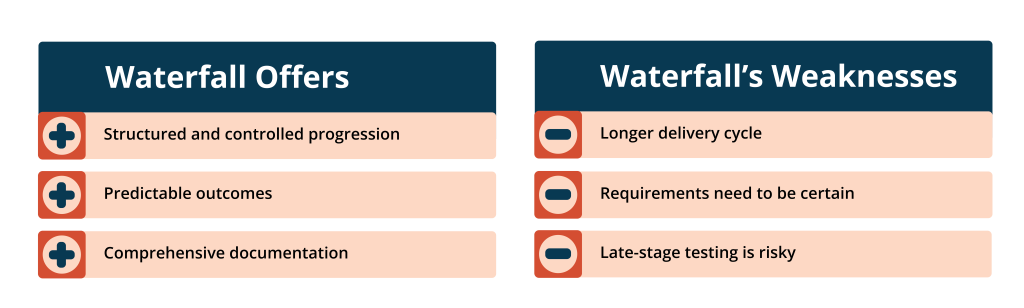

As its name suggests, the waterfall method involves a sequential downward “flow” of work through distinct phases. Before the project begins, the problem/opportunity is defined, and a feasibility analysis is conducted. Then the project is formally initiated. Stakeholder requirements are gathered and lead to the design of the full solution. Once design is complete, comprehensive implementation planning occurs. The solution is then built (commonly called “construction”). The solution is then tested and rolled out. A formal handover to the operating unit(s) that will maintain the solution is the final step before the project is closed. Many organizations have “phase gates” to ensure the work of one phase has been successfully completed before the project proceeds to the next phase. As Figure 4.4 depicts, the waterfall approach has strengths and weaknesses.

Exhibit 4.5: Strengths and weaknesses of waterfall.

Many in the project management community believe “waterfall is dead”. This is not the case, and they are many successful projects still using this methodology. The Bassein Development Project in India is an example of a very successful project that was completed in record time using the waterfall methodology. Note the importance of rigorous planning, detailed documentation, and stakeholder communication in this article of the project’s success.1 Also note that it was important for the engineering firm who completed the project, L&T Hydrocarbon Engineering Limited (LTHE), to commit to a project budget and timeline upfront.

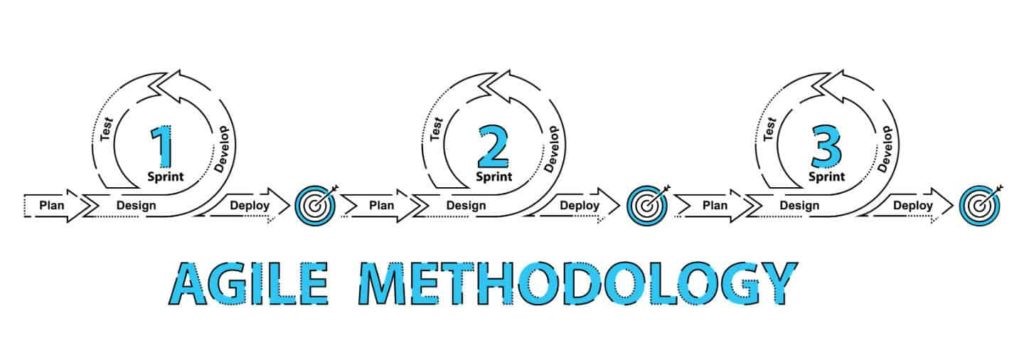

Agile

Agile is here to stay. Scott Ambler, VP and Chief Scientist of Disciplined Agile at PMI, believes, “Agile isn’t just a trend, it’s here to stay…especially as we better learn how to effectively yield its benefits.”2 Agile is an overarching term. It refers to a family of project delivery frameworks that promotes adaptive, incremental solution development versus sequential solution development. Exhibit 4.4 depicts the agile approach as a series of smaller iterations; this is in contrast to the single development effort used in predictive development methodology.

Exhibit 4.6: The adaptive nature of Agile

Tricentis

Agile is no longer just used on technology projects. In addition, there are now many different types of agile methodologies. These methodologies guide development teams in identifying user requirements and creating manageable chunks of development effort. In addition, there are numerous testing methodologies to chose from. Recognizing that “one size does not fit all,” it is important to consider organizational size, organizational culture, and the needs/preferences of stakeholders when deciding if and how agile will be used in a project. Agile as a development methodology could easily become a textbook and course all on its own. Listed below are various agile frameworks and practices.

Frameworks:

- Scrum

- SAFe

- Crystal

- Kanban

- eXtreme Programming (XP)

- Feature-driven programming

Practices:

- Timeboxing

- User stories

- Daily stand-ups

- Frequent demonstrations

- Test-driven development

- Information radiators

- Retrospectives

- Continuous integration

Since the goal of this textbook is to provide an overview of the fundamentals of project management, an overview of one of the most popular methodologies, Scrum, will be provided.

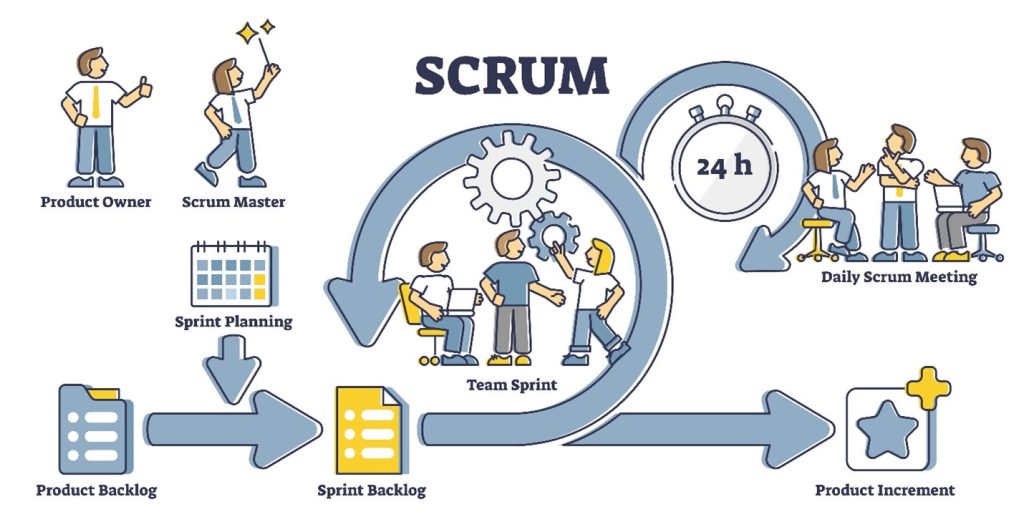

Scrum

Scrum is a term from rugby (scrimmage) that refers to a way of restarting a game. It is like restarting the project efforts every few weeks. It is based on the idea that you do not really know how to plan the whole project upfront, so you start with what you know and then re-plan/iterate from there.

Solutions start with a vision. A vision (often called an epic) is the rough outlines and boundaries of the solution. It frames the organizational value to be delivered by the project. It serves as the starting place for analyzing what is required. Through analysis, the required capabilities and enablers are identified. The features (deliverables that will fulfill stakeholder needs) of each capability are then identified. These features can then be further broken down into user stories to represent smaller pieces of the functionality. The user stories go into a product backlog. The product owner prioritizes the user stories during sprint planning sessions. These stories form the sprint backlog. Each sprint typically takes the development team 2 to 4 weeks to complete.

Exhibit 4.7: The scrum planning process (Source: Adobe Stock Image)

Planning meetings for each sprint require participation by the product owner, the scrum master, and the development team.

- Product owner: essentially the business owner of the project who knows the industry, the market, the customers, and the business goals of the project.

- Builds consensus within the end-user community.

- Communicates end-user expectations to the development team.

- Provides acceptance on completed feature definitions in the solutions and the completed user stories.

- Usually accountable to the project sponsor. If the project has two project sponsors (one from the business and the other from IT), the product managers would report to the business sponsor.

- “Owns” the content (what is built and in what sequence).

- Business area lead (subject matter expert or SME): is from a particular business unit and may be an end-user or directly represents the end-users.

- Works very closely with the product owner to develop the vision for the solution.

- Helps clarify business needs and expectations.

- Scrum master:

- Removes barriers that impede the progress of the development team.

- Helps the product owner maximize return on investment (ROI) in terms of development effort.

- Facilitates creativity and empowerment of the team.

- Improves the productivity of the team, as well as engineering practices and tools.

- Runs daily stand-up meetings.

- Tracks progress.

- Ensures the overall health of the team.

- Development team: a highly empowered group that participates in planning and estimating for each sprint.

- Develops the solution in sprints.

- Demonstrates the results at the end of the sprint.

- Sometimes (depending on the organization) involved in testing, including functional testing (confirming the software requirements have been met) and non-functional testing (security, usability, performance).

In sprint planning meetings, goals are set for the upcoming sprint and a subset of the product backlog (proposed user stories) is selected to be worked on. The development team decomposes stories into tasks which are then estimated. The product owner then finalizes the backlog for the following sprint. The planning cycle continues until the solution has been completed in its entirety.

The role of the project manager in a scrum deployment varies by organization. Some organizations give some of the project manager’s accountabilities (particularly arranging for project funding, risk management, and iteration planning) to the product owner. However, the team management aspects are less likely to be assigned to the owner because they often require a significant time commitment. In these cases, a project manager may be assigned to lead the project team and manage the budget and schedule commitments of the project. This frees the product owner to focus on what is being built as well as the end-user community. When all three roles – product owner, scrum master, and project manager – are present on the project, they all must work toward project success in a highly collaborative fashion.

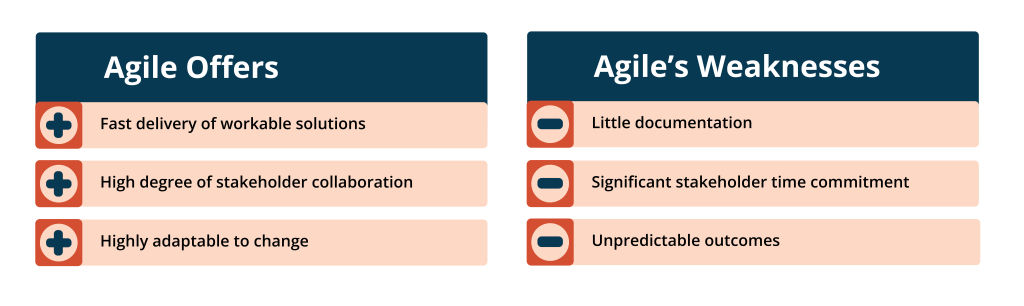

Every methodology has strengths and weaknesses. Figure 4.8 is a depiction of the strengths and weaknesses of Agile:

Exhibit 4.8: Strengths and weaknesses of Agile.

Exhibit 4.8: Strengths and weaknesses of Agile.

There are many successful projects that have used an Agile methodology. Spotify, the world’s most popular audio subscription service, has 574 million users and operates in more than 180 markets.3 Spotify is very responsive to changing market conditions and evolving customer needs. It now offers much more than music. Users now have access to thousands of podcasts and audiobooks. In addition, the Spotify platform has evolved to create a community for artists and listeners. Lastly, Spotify uses AI to give listeners their very own DJ4. How Spotify evolved is just as exciting as the products and services they offer. Spotify organizes people around work and each team has a purpose – improving the Android client, creating the Spotify radio experience, scaling the backend systems or providing payment solutions.5 Each autonomous team selects their own agile methodology and operates on the basis of producing a minimum viable product (MVP) which is quickly deployed to the Spotify platform.6 Continuous customer feedback loops allow the product to evolve in response to customer needs.7

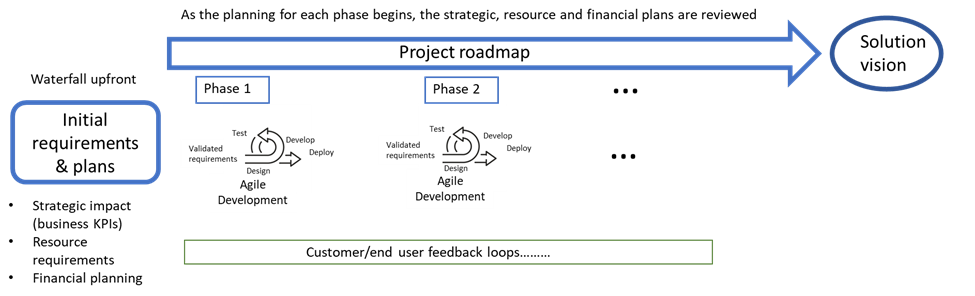

As the world becomes increasingly complex, introducing sustainable change requires project leaders to utilize highly tailored approaches. Many projects have diverse stakeholder needs and a significant number of internal and external interdependencies; As a result, the use of a hybrid methodology is on the rise.

Exhibit 4.9: Hybrid is a balanced approach.

As noted earlier, projects that have a mix of well-defined and poorly defined aspects of the solution are well-suited to a hybrid methodology. A simple example of a project that would benefit from a hybrid methodology involves the deployment of new technology, an office move, and a reorganization of staff reporting relationships. The requirements of the new technology may not be well-defined while the requirements associated with the office move and organizational structure changes could be well-defined. An agile methodology would be used to develop the technology solution and the waterfall approach would be used to design the new office location and organizational structure. An effective deployment approach would be developed for the various aspects of this project.

For projects that are developing a single solution, there are many ways to structure the approach using the hybrid methodology. For instance, the waterfall approach can be used to develop the initial requirements and plans. Agile can be used to refine the requirements by getting feedback from customers and other stakeholders and release the solution in multiple deliveries (increments). Each delivery adds new features and functionality. Exhibit 4.9 depicts this approach.

Exhibit 4.10: An example of an approach used with the Hybrid methodology.

Variations of this approach are possible if stakeholders prefer a single release of all the features and functionality. Multiple development phases can still occur to allow for a strong link between customer feedback and solution design. This approach would leverage a key strength of the agile methodology – adaptability. However, instead of having a delivery at the end of each phase, the outcomes of the phases can be bundled into a single release at the end. This is an adaption of waterfall’s approach single release methodology and is ideal when the solution is only usable in its entirety or imposing frequent change on end users is discouraged.

Tesla uses the hybrid approach to launch new products. The design and launch of its Gigafactory follows the Waterfall approach. The project begins with Site Selection then sequentially moves to Initial Project Design, Partner Discussions, Zoning and Design/Build, Facility Construction, Equipment Installation and finally Production Launch.8

Tesla uses an agile approach to introduce new features and functionality in its electric vehicles. This allows Tesla to remain responsive to customer feedback while getting vehicles to market as quickly as possible.9

In summary, all development methodologies can be effective, in the right situation. After the most appropriate development methodology has been selected, the next step is to select the appropriate tools and techniques that will help the team achieve the project’s objectives. There are many factors to consider in selecting tools and techniques. Some of the key factors include:

- size, skill and geographic location of the team

- complexity of the existing technology platforms

- maturity and efficiency of the business processes

- change readiness of the organization

To illustrate how these factors impact the tools and techniques used on a project, consider a project team consisting of 50 people who have little or no experience with agile methodologies. The individuals in the team will be dispersed across 3 countries – Canada, the US, and the UK. The team will be introducing new technology into an organization and the vision for the end solution continues to evolve. An agile methodology would be well-suited to this type of project, given the uncertainty surrounding the requirements. The team will need training, highly effective performance coaching techniques and regular team building sessions to help them build trust in a virtual environment. Much of this would not be required if the team was co-located and had experience with agile methodologies.

Additional resources:

References

1 Larsen & Toubro Limited. (2023). Bassein Development Project – Fast Tracked Success Story. https://newsnviews.larsentoubro.com/Lists/Posts/Post.aspx?ID=186

2 Ambler, S. (2019). The Most Important Agile Trends to Follow in 2020. Information Week. https://www.informationweek.com/strategic-cio/enterprise-agility/the-most-important-agile-trends-to-follow-in-2020/a/d-id/1336550

3 Spotify. (2024). https://investors.spotify.com/about/default.

4 Kniberg, Henrik. & Ivarsson, Anders. 2012, October. Scaling Agile @Spotify with Tribes, Squads, Chapters & Guilds. https://investors.spotify.com/home.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Adhikari, Richard. (2014, August). Panasonic to Help Make Tesla’s Gigafactory Materialize. Tech News World. https://www.technewsworld.com/story/panasonic-to-help-make-teslas-gigafactory-materialize-80821.html

9 Bellon, Tina, Jin, Hyunjoo and Shepardson, David. (2022, February). Telsa software updates allow quick fixes – and taking risks. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/tesla-software-updates-allow-quick-fixes-taking-risks-2022-02-18/