3. Project Structures and Organizational Culture

3.1 Introduction to Project Structures

Many organizations determine who should lead a change initiative by evaluating its complexity before resources are assigned. Complexity can be assessed in many ways. Many organizations consider the number and nature of people impacted, the priority and urgency of the change being introduced, and the degree of risk associated with the change. Examples of risks:

- The potential to lack the necessary resources and skills to support the project.

- The potential that the cost of materials may increase past what is allocated in the budget.

There are three primary organizational structures used in project delivery: functional, dedicated, and matrix.

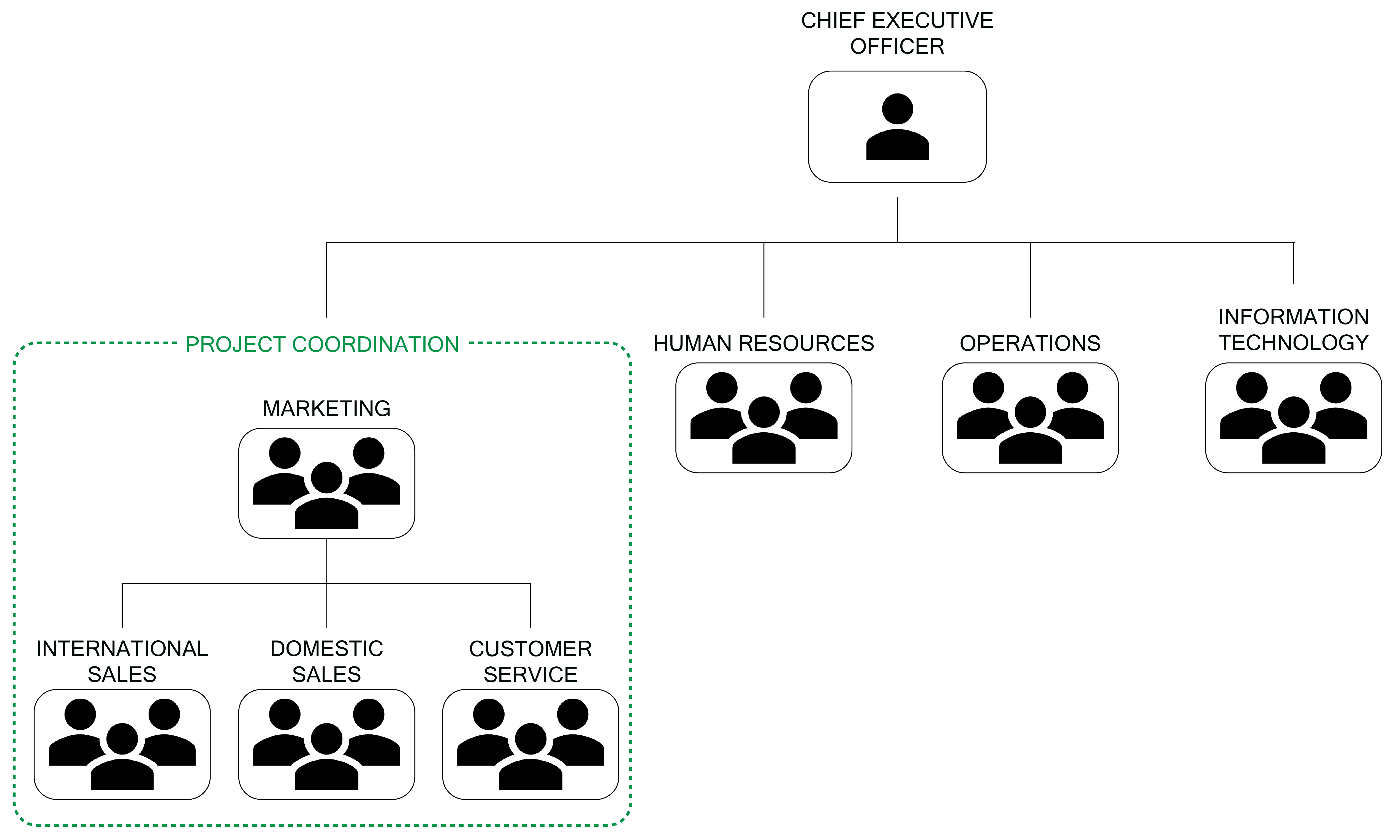

Functional Project Team Structures

Small, low complexity change initiatives are often delivered by departmental resources. These resources may be department managers (e.g. marketing manager, manufacturing manager) or individual contributors carrying out the day-to-day work of the department. Regardless of their role, it is important to note that these individuals are participating in a change initiative in addition to fulfilling their day-to-day responsibilities. In this case, a professional project leader is not assigned to lead the change initiative. Since the change is being delivered by a particular department (function), it is commonly referred to as the functional project structure.

Functional project structures are effective ways to introduce change into an organization when the change primarily impacts one function and the skills required to deliver the change are available in the department. This becomes an efficient use of resources because the organization does not have to incur the cost of hiring people to work on the project or fill in for functional resources temporarily re-assigned to a dedicated project team. In addition, the team of individuals working on the project will have existing relationships with each other and their leader. When these relationships are good, this can accelerate the effectiveness of the team.

However, the functional project structure comes with its own unique set of challenges. The first relates to the potential for loosely defined accountabilities on the project. When it comes to decision-making, a lack of clear authority can be particularly problematic. Functional project teams are often informally created and managed. As a result, roles and responsibilities are often implied versus formally defined. It is important that the sponsor of the change initiative clearly establishes accountabilities and responsibilities in order to facilitate effective decision-making and reduce the likelihood of team conflict.

Secondly, the members of the functional project team may face an unrealistic workload when expected to maintain their day-to-day accountabilities and complete project deliverables. This can lead to conflict and burnout. In selecting people to work on a project in a functional structure, it is important that individual capacity and skill are considered. Furthermore, the impact of these workload challenges often appears as project delays occur. When faced with a choice of what to work on, functional project team members often select their day-to-day accountabilities over the work of the project. This occurs because an individual’s compensation and performance evaluation are often more directly influenced by the quality of the work performed in their functional positions. As a result, functional structures can be the slowest method of introducing change into an organization.

Lastly, given the insular nature of a project delivered in a functional structure, it may be difficult for the team to get the support they need from people outside of their functional team. This occurs because the project is a priority for the functional team but rarely for other departments outside of the particular function. In addition, technical resources may be focused on the delivery of high-visibility projects with organizational-wide benefits.

In conclusion, functional project structures work well for change initiatives that primarily involve a single department and are not highly complex. When these conditions are not present, other project structures are more appropriate.

Exhibit 3.1: Functional team structure diagram illustrating project coordination occurring within a department (function).

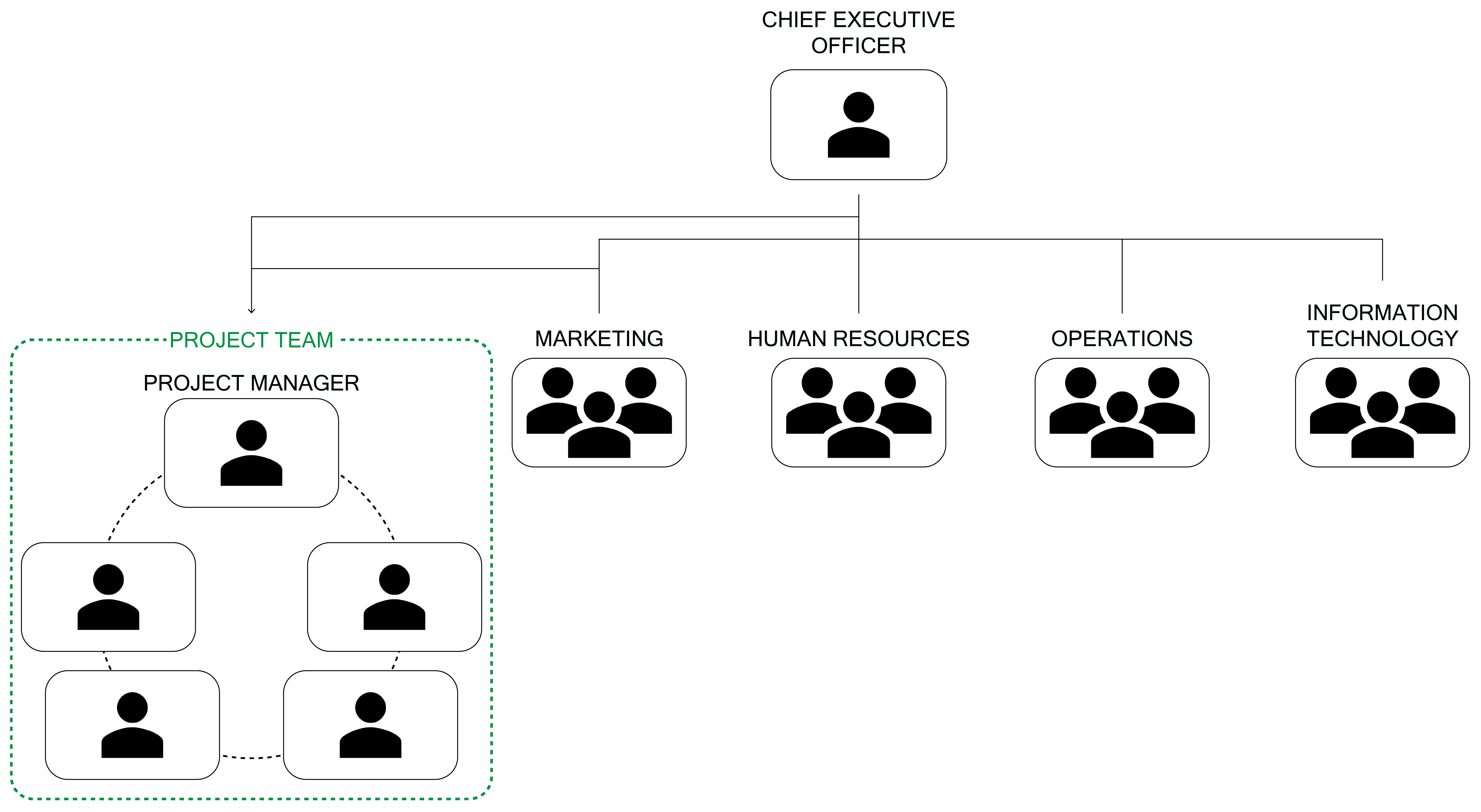

Dedicated Project Team Structures

The opposite of a functional project team structure is the dedicated project team structure. In this organizational model, all members of the project team are working exclusively on the project. Members of these teams have either been hired specifically for the project, perhaps externally, or have been temporarily reassigned from an existing functional team. This structure, although the most expensive, can be the fastest way to introduce change into an organization. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, dedicated project team structures are often more formally approved and recognized. The recognition often creates a greater sense of urgency and this, in turn, may result in the leaders of the organization allocating the necessary supports required for successful project delivery, such as timely reviews of project deliverables. Secondly, unlike the functional project team structure, a project leader is assigned to lead the project team. The project leader may be full-time or part-time, depending on the size and complexity of the change initiative. The project leader ensures that the project team is aware of the project’s objectives, stays focused on the project’s deliverables, and clarifies the accountabilities of the various team members. In turn, the project team members do not have to balance their day-to-day work like members of project teams do in a functional project structure. This alone can allow for faster completion of the project work as compared to the functional project structure.

Despite all the advantages of this structure, an organization may not be able to afford the dedicated model. In addition, if the project team is not carefully selected, it may lack the subject matter expertise required to successfully introduce change into the function(s) impacted. When an organization chooses to hire people from outside the organization, they are unlikely to be familiar with the culture, processes, and procedures of the organization. When this happens, the dedicated project team needs to include a sufficient number of internal subject matter experts who bring this knowledge to the team. If this is not possible, the project team needs timely access to these experts as required. This is a critical success factor of this model. Resource constraints are a reality for many organizations, often leading to the use of the third project structure – the matrix organizational model.

Exhibit 3.2: Dedicated team structure diagram illustrating project coordination occurring within a dedicated project team that may report back to a department (e.g. marketing manager), which is typically the case in lower complexity projects, or directly the chief executive officer (CEO), which is more likely to occur in higher complexity projects.

Exhibit 3.2: Dedicated team structure diagram illustrating project coordination occurring within a dedicated project team that may report back to a department (e.g. marketing manager), which is typically the case in lower complexity projects, or directly the chief executive officer (CEO), which is more likely to occur in higher complexity projects.

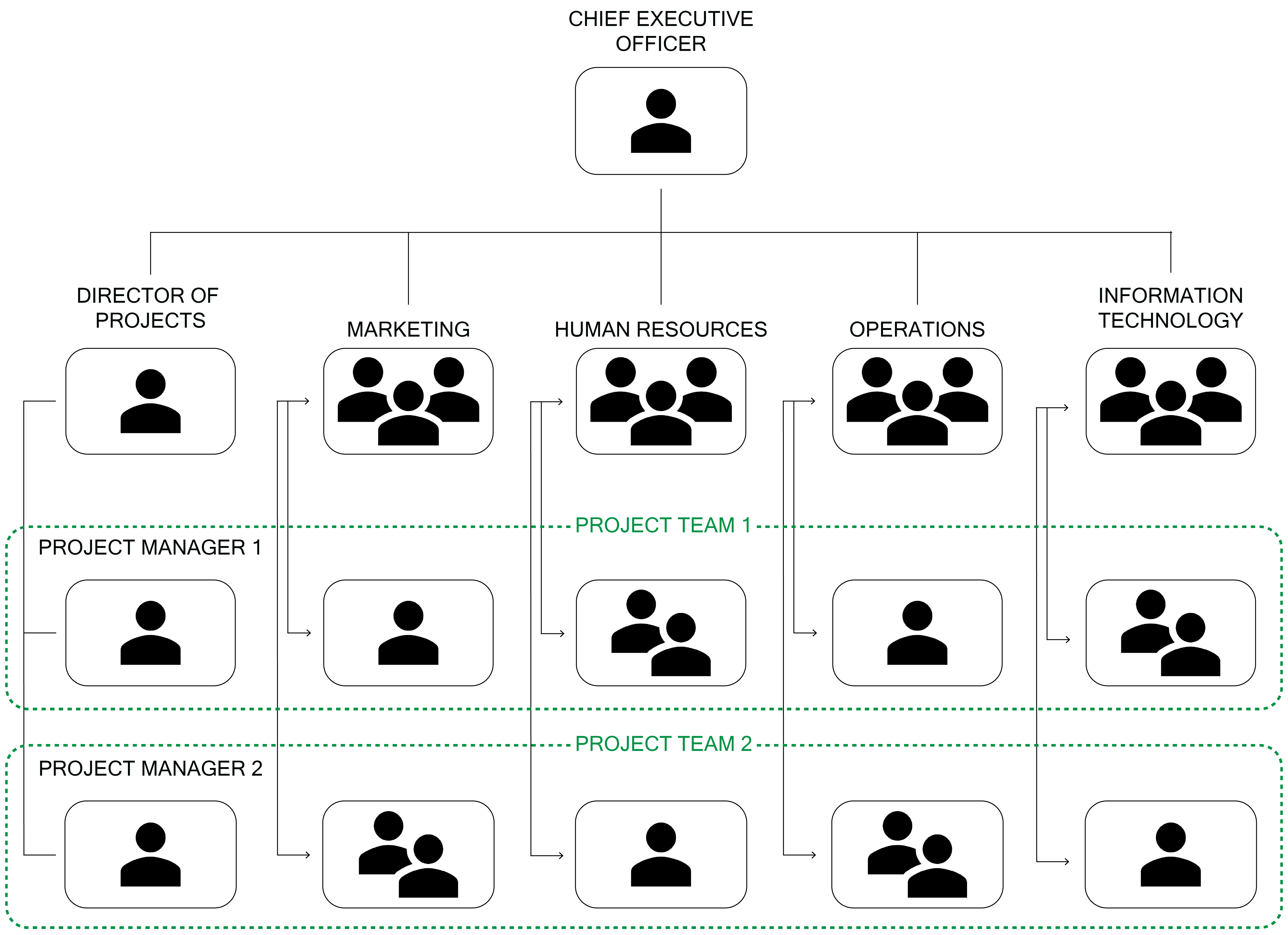

Matrix Project Team Structures

As the name implies, the matrix project structure is a mix of the functional and dedicated structures. Projects are delivered by resources that remain in their functional structures. However, they also report to a project leader. By assigning a project leader, the organization attempts to ensure the project’s objectives are formalized and progress is monitored. In addition, the project leader will use their project management and leadership skills to increase the likelihood of project success. Having a project leader who is accountable for the work helps ensure that best practices are followed, individual team member responsibilities are clear, and the team remains committed to the project’s deliverables and objectives. This structure seems like the ideal model to deliver change – subject matter experts (engineers, manufacturers, marketers) carry out the work and they have the benefit of a skilled project leader to mentor them along the way. However, this structure can be stressful for all parties involved. From the project team’s perspective, reporting to two people can be really challenging, especially if their functional manager and project leader are not effective communicators. From the project leader’s perspective, despite being accountable for project success, they may have little influence over who does the work and when it is done. This is because they have to negotiate with the functional manager(s) in order to obtain the resources they need when they need them. On the other hand, functional managers must balance allocating resources to achieve their operational targets as well as to ensure the project’s success. If a functional manager does not share accountability for project success alongside the project leader, they are unlikely to be willing to free up the needed resources if it means their operational targets may become harder to achieve. From the perspective of the functional manager, a project may offer them numerous future benefits, such as improved productivity or the potential for greater client satisfaction. However, these benefits may seem too far in the future and may not be fully considered if their immediate operational targets are difficult to achieve. Naturally, the project leader and the functional manager will attempt to negotiate for the outcomes most desirable to them. Power struggles can lead to unhealthy conflict, leaving the project team members in stressful situations. Much of this can be avoided if the priority of a project has been clearly communicated by the organization’s executive team, and the performance of the project leader and functional manager(s) are appropriately linked in order to encourage an environment of cooperation.

Exhibit 3.3: Matrix team structure diagram illustrating project coordination occurring in a way where an employee is reporting to a project manager for their project team duties while also reporting to a department manager for their departmental duties. In some instances, project managers may report to their own “department manager,” the director of projects.

Exhibit 3.3: Matrix team structure diagram illustrating project coordination occurring in a way where an employee is reporting to a project manager for their project team duties while also reporting to a department manager for their departmental duties. In some instances, project managers may report to their own “department manager,” the director of projects.

Determining which organizational structure to use at any given time often involves a mix of practical and strategic considerations. From a practical perspective, if the organization lacks the financial resources required to set up a dedicated project team, this leaves two alternatives – the functional or matrix structures. A key strategic consideration is the importance of the project. High-priority projects with aggressive timelines are not well suited to the functional project team model because it is the slowest of the three. In situations where funds are limited, the matrix structure is preferred over the functional model.

Some organizations carry out a lot of projects. This is often the case in rapidly changing markets and in organizations going through significant internal transformation. In these cases, investments are often made to establish permanent project teams that are able to lead the organization’s various change initiatives. In extreme cases, organizations that view project delivery as a core aspect of their day-to-day activity can adopt a projectized environment. In projectized environments, the traditional hierarchal and function-based management structure gives way to a flatter team-oriented structure which is often more agile in nature.

3.2 Introduction to Organizational Culture

Organizational culture refers to the beliefs, attitudes, and values that are shared by the organization’s members. Organizational culture sets one organization apart from another and dictates how members of the organization see, interact, and (sometimes) judge other employees. Often, project teams have a specific culture, work norms, and social conventions.

Some aspects of organizational culture are easily observed; others are more difficult to discern. You can easily observe the office environment – where people work (closed versus open spaces), how people dress, and how people speak. The subtler components of corporate culture, such as the values and overarching philosophy, may not be readily apparent, but they are reflected in the behaviours, symbols, and conventions used by members.

Exhibit 3.4: Consider these two different office environments. How do closed vs. open spaces reflect corporate culture?

Pixabay, Unsplash

Organizational culture is considered one of the most important internal dimensions of an organization’s effectiveness criteria. Peter Drucker, an influential management guru, once stated, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”1 By this, Drucker meant that corporate culture is more influential than strategy in terms of motivating employees’ beliefs, behaviours, relationships, and ways they work since corporate culture is based on corporate values. Strategy and other internal dimensions of the organization are also very important, but organizational culture serves two crucial purposes. First, culture helps an organization adapt to and integrate with its external environment by adopting the right values to respond to external threats and opportunities. Secondly, culture creates internal unity by bringing members together so that they work more cohesively to achieve common goals. Culture is both the personality and glue that binds an organization. It is also important to note that organizational cultures are generally framed and influenced by the top-level leader or founder. This individual’s vision, values, and mission set the “tone at the top,” which influences both the ethics and legal foundations, modelling how other executives and employees work and behave. A framework used to study how an organization and its culture fit with the environment is offered in the competing values framework (CVF).

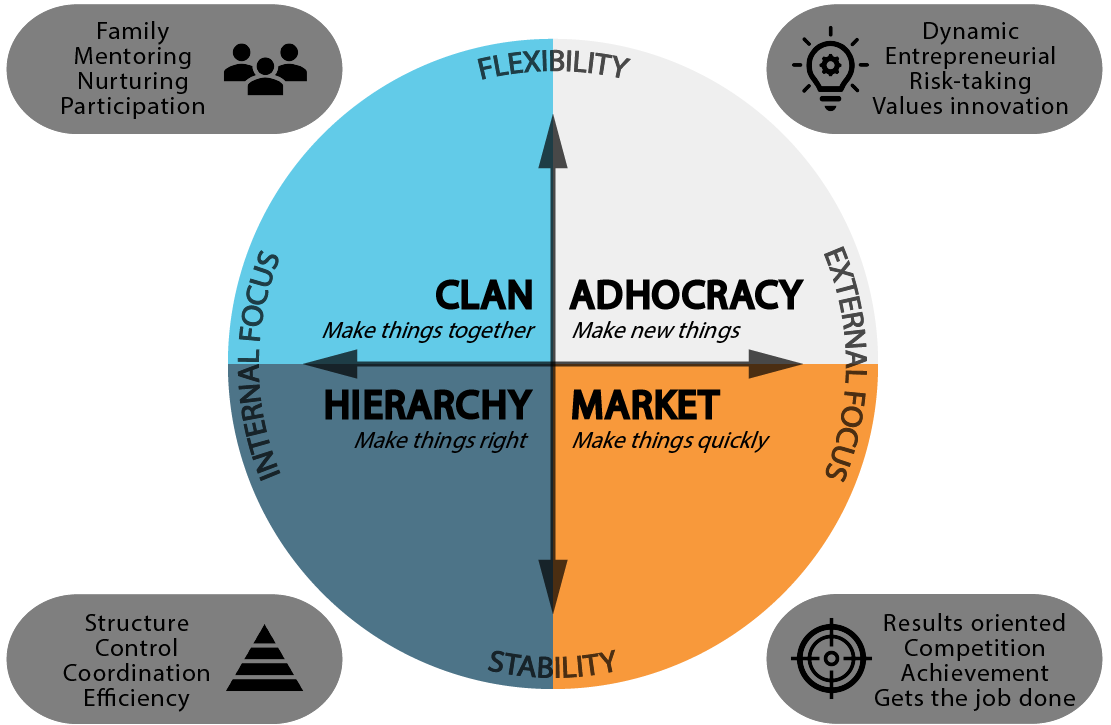

The CVF is one of the most cited and tested models for diagnosing an organization’s cultural effectiveness and examining its fit with its environment. The CVF, shown in Exhibit 3.5, has been tested for over 30 years; the effectiveness criteria offered in the framework were discovered to have made a difference in identifying organizational cultures that fit with particular characteristics of external environments.2

Exhibit 3.5: The competing values framework.

.The two axes in the framework, external focus versus internal focus, indicate whether or not the organization’s culture is externally or internally oriented. The other two axes, flexibility versus stability and control, determine whether a culture functions better in a stable, controlled environment or a flexible, fast-paced environment.

Combining the axes offers four cultural types:

1. The dynamic, entrepreneurial adhocracy culture – an external focus with a flexibility orientation

- Emphasizes creating, innovating, visioning the future, managing change, risk-taking, rule-breaking, experimentation, entrepreneurship, and uncertainty

- Found in fast-paced industries, such as filming, consulting, space flight, and software development

- In larger organizations with adhocracy culture, such as Facebook and Google3, a different subculture may evolve within one department (e.g., marketing or finance) of an organization, and it may be quite different than the larger, dominant culture of the organization

2. The people-oriented, friendly clan culture – an internal focus with a flexibility orientation

- Emphasizes relationships, team building, commitment, empowering human development, engagement, mentoring, and coaching

- Found in human development, team building, and mentoring organizations, such as the Olympians of Team Canada, which has strived to form respectful relationships with employees, customers, suppliers, and the physical environment

3. The process-oriented, structured hierarchy culture – an internal focus with a stability/control orientation

- Emphasizes efficiency, process and cost control, organizational improvement, technical expertise, precision, problem-solving, elimination of errors, logical and conservative management and operational analysis, and cautious decision-making

- Found in bureaucratic and structured organizations, such as the military and other government agencies

4. The results-oriented, competitive market culture – an external focus with a stability/control orientation

- Emphasizes competing and delivering results, delivering shareholder value, goal achievement, speedy decisions, hard-driving through barriers, directive, commanding, and getting things done

- Found in marketing-and-sales-oriented organizations that work on planning and forecasting, but also getting products and services to market and sold, such as Oracle and its dominating, hard-charging executive chairman Larry Ellison

Working Within a Culture

Some cultures are more conducive to project success than others. As a project leader, it is very important to understand the unique nature of the corporate culture that we operate in. This understanding allows us to put in place the processes and systems most likely to lead to project success. Consider the following scenario:

Assume you are leading a project in an organization with a hierarchical culture. Projects are about changing the way an organization operates. Introducing change in an organization with this type of culture can be very challenging because they value caution, conservative approaches, and careful decision-making. If the project you are leading involves the introduction of innovative practices and technologies, it may be very difficult and time-consuming to get the approvals required to proceed with the project at its various stages. Innovative practices are not guaranteed to work; success requires a high degree of risk tolerance in decision-making processes. This may be difficult to achieve in organizations with this type of culture. Furthermore, the already aggressive schedule of employees in hierarchal organizations may not be able to accommodate the potential numerous and lengthy deliverable reviews required for innovative projects, causing project success to be viewed as unachievable. Project leaders in this type of culture are wise to speak openly and candidly about the project’s risks and plan for additional deliverable reviews as a way of setting the project up for success. If this very same innovative project was being delivered in an organization with a market culture, the decision-making approach and the schedule are likely to be fundamentally different.

Furthermore, communication methods can be adapted to suit the unique nature of the project. This adaptation will also strongly affect project success. Key questions the project team needs to address are:

- Which stakeholders will make the decision in this organization on this issue? Will your project decisions and documentation have to go up through several layers to get approval? If so, what are the criteria and values that may affect acceptance there? For example, is cost, quality, or being on schedule the most important consideration?

- What type of communication among and between stakeholders is preferred? Do they want lengthy documents? Formal or informal communication? Is “short and sweet” the typical standard?

- What medium of communication is preferred? What kind of medium is usually chosen for various situations? Check the lessons learned repositories to see what past projects have done or ask others in the organization.

References

1 Hyken, S. (2015, December 5). Drucker said culture eats strategy for breakfast. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/shephyken/2015/12/05/drucker-said-culture-eats-strategy-for-breakfast-andenterprise-rent-a-car-proves-it/#7a7572822749

2 Cameron, K., Quinn, R., Degraff, J., & Thakor, A. (2014). Competing values leadership (2nd ed.). Edward Elgar Publishing; Cameron, K., & Quinn, R. (2006). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. https://www.ocai-online.com/blog/2016/09/Organizationalculture-Create-Collaborate-Control-Compete

3 Yu, T., & Wu., N. (2009). A review of study on the competing values framework. International Journal of Business Management, 4(7), 37-42.