Unit 14: Decolonizing the Canadian Workplace

Tricia Hylton

Learning Objectives

After reviewing this information, you will be able to:

After reviewing this information, you will be able to:

-

-

- Define decolonization

- Explain the differences between the colonial and Indigenous worldviews

- Identify structural and individual strategies to decolonize the workplace

-

Introduction

“Colonialization as a system [did] not go away, it remains”

(Decolonisation, 2023)

One of the many misconceptions about colonization is that it ended when colonizing powers departed occupied lands. However, in Decolonisation (2023), Dr. Ndlovu-Gatsheni explained that the departure of colonial powers from occupied lands only signified the “end of colonization as an event” (2:45), not of colonialism as a system. Colonialism was not simply the occupation of land and the stealing of resources. Colonialism also involved instituting the colonial worldview: the process of replacing the values, beliefs, economic, political, and educational systems of Indigenous populations with those of the colonizing nation (Deconlonisation, 2023; Wilson & Hodgson, 2017). Dr. Ebalaroza-Tunnell (2024) states, “Colonialism wasn’t just about physical land grabs; it also imposed dominant ideologies and systems of knowledge…that prioritized Eurocentric viewpoints, hierarchical structures, and an “extractive” approach to work” (para. 7).

For persons and nations once colonized, the colonial worldview has resulted in many detrimental effects. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (n.d.) and the United Nations High Commission (2023) argue that the cause of modern-day discrimination, inequality, and injustice is rooted in colonialism. Specifically, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (n.d.) states that a direct connection exists between colonialism and

- contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, and xenophobia, and

- intolerance faced by Africans, people of African descent, people of Asian descent, and Indigenous Peoples.

In addition, The United Nations High Commission (2023) adds the following groups to those negatively impacted by the colonial worldview:

- persons of diverse sexual orientations,

- persons of diverse gender identities and expressions and/or sex characteristics, and

- women and children.

This understanding of colonization is important when discussing decolonization. Introduced in Unit 11: Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion: Terminology, decolonization involves a very intricate and complex process of breaking down the ideologies, systems, and structures established by the colonial worldview, and normalized over time, to establish new ideologies, systems, and structures (Decolonisation, 2023). This Unit does not propose to examine the full breadth of issues associated with decolonization. Instead, this Unit will take a specific look at decolonization as a strategy to deconstruct the ideologies, systems, and structures that exist in the Canadian work environment.

The Colonial Worldview and Its Impact

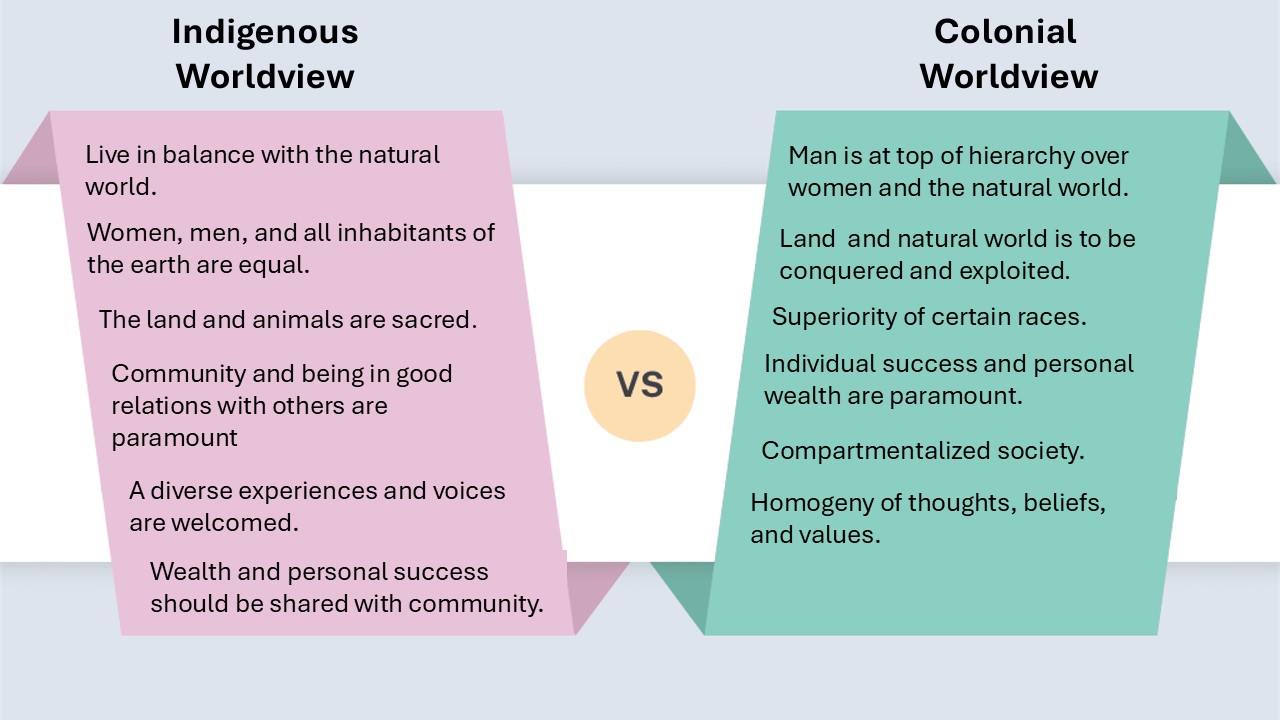

We’ll begin our discussion by examining the characteristics of the colonial worldview and how these characteristics materialize in the Canadian work environment. Common characteristics of the colonial worldview include:

- Valuing individualism and competition and seeking success for oneself above all else,

- Believing the environment and its resources can be owned and exploited for the accumulation of wealth and personal enjoyment,

- Instituting a hierarchical order in society that declares some (e.g. men) as more important, powerful, and influential than others (e.g. women),

- Placing importance on the accumulation of material things as a symbol of status and power, and

- Acknowledging only one correct view of the world.

(Intercultural Communications, n.d.; Wilson & Hodgson, 2018; Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc. 2016; Ermine, 2007).

Case Study 1 provides two examples of how these characteristics are experienced in the Canadian workplace by members of racialized and marginalized groups.

Case Study 1: The Canadian Public Service

According to the Canadian Encyclopedia (2013), the Canadian Public Service supports the development and administration of government services such as healthcare, national defence, and justice. Those within the Public Service act as agents of the presiding government, elected officials, and governmental departments. In this role, the Public Service is a reflection and representative of Canadian values. The following two examples detail the experience of two racialized and marginalized groups employed in Canada’s Public Service.

Example 1:

The Black Executives Network (BEN), a support group of Black executives working in the federal Public Service, released a report in November 2024 based on interviews with 100 current and former Black Public Service executives. The report detailed the experience of systemic racism endured by former and current members of the BEN in the Public Service. Some of the more disturbing findings in the report include:

- being called the N-word

- being threatened with physical violence,

- being denied career advancement opportunities,

- enduring instances of workplace harassment and intimidation,

- encountering threats of reputational harm, and

- having the merit of professional credentials, experience, and position questioned and/or undermined.

(CBCNews, 2024)

Example 2:

The report, Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation (2017), details the experiences, barriers, and challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples working in the Public Service. Based on 2,100 responses from current and former Indigenous Public Service employees, the following are some the more important challenges and barriers encountered:

- undervaluing of experience and expertise,

being denied career advancement and promotion opportunities,

being denied career advancement and promotion opportunities,- experiencing unfair and inaccessible hiring practices,

- enduring general harassment and discrimination practices, and

- combatting lack of respect for Indigenous cultures.

Of note, the report also found that Indigenous employees reported significantly higher levels of harassment and discrimination than non-Indigenous employees and that only 3.7% of senior positions in the Canadian Public Service were held by an Indigenous Person (Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation, 2017).

The experiences of Black executives and Indigenous employees in Canada’s Public Service are disturbing, and should be. The importance of these negative interactions occurring in Canada’s largest single employer (CBCNews, 2024) cannot be overstated. However, as untenable as these practices are, the question that must be asked and answered is do these practices embody the characteristics of the colonial worldview?

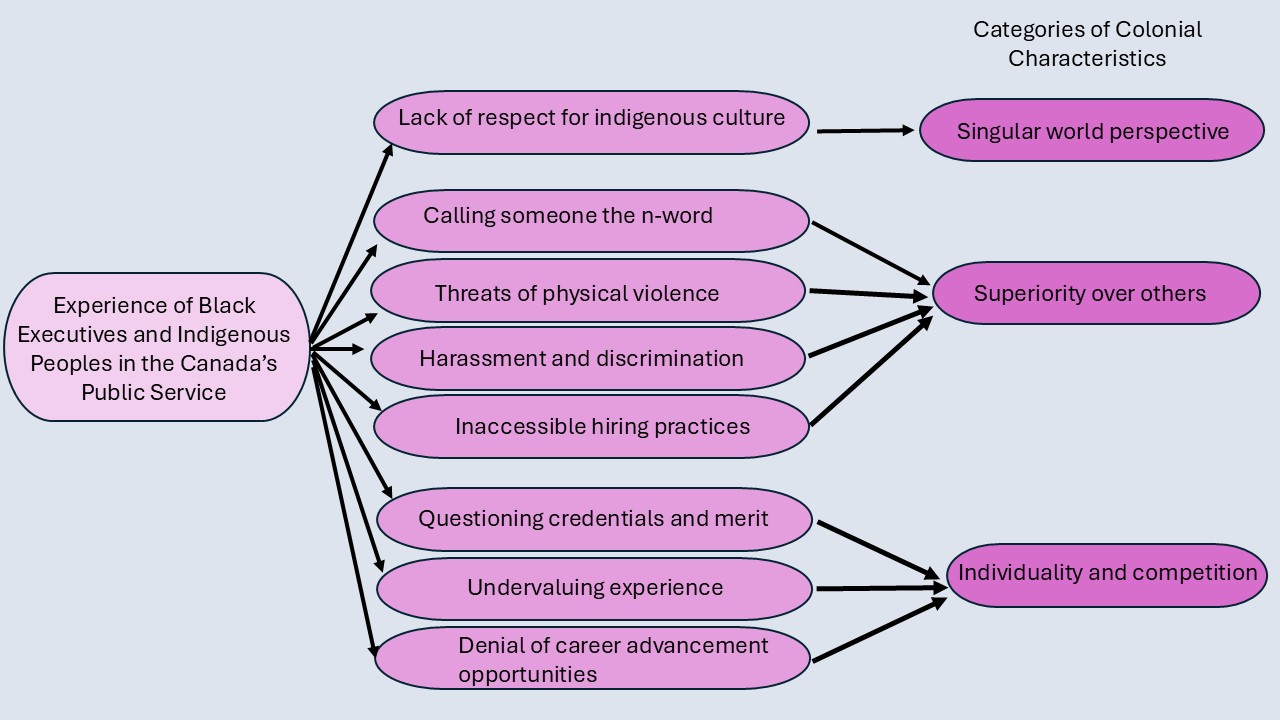

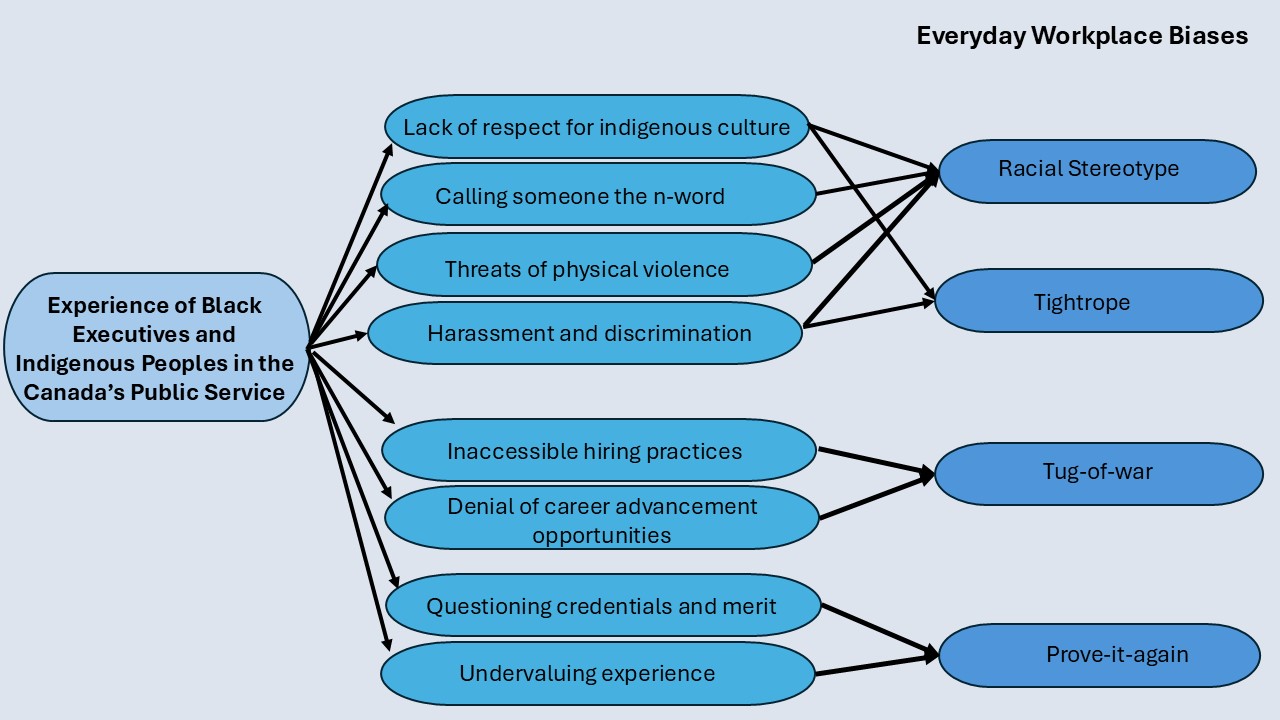

One measurement to answer this question is to assess the noted negative behaviours towards Black executives and Indigenous Public Service employees against the characteristics of the colonial worldview described above (Intercultural Communications, n.d.; Wilson & Hodgson, 2018; Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc. 2016). An analysis of Figure 14.1 reveals that the treatment of Black executives and Indigenous employees fall under three categories of the colonial worldview: adherence to a singular worldview, acceptance of the notion that some are superior to others, and validation of individualism and competition.

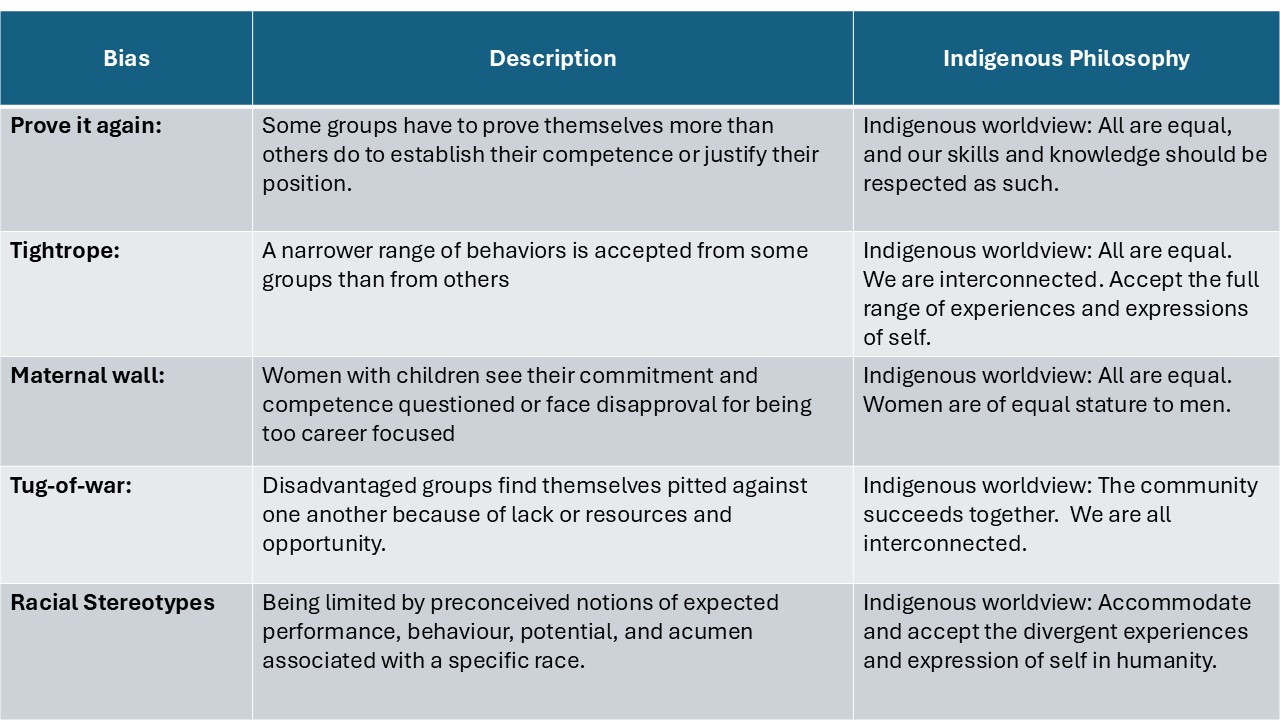

A second measurement to answer the question: do the practices towards Black executives and Indigenous Public Service employees embody the characteristics of the colonial worldview was introduced in Unit 12: EDI in the Canadian Workplace. There, Williams (2020) offers the finding of a 10-year study that identified five patterns of bias experienced in everyday business interactions: the tightrope bias, the maternal wall bias, the racial stereotype bias, the tug-of-war bias, and the prove-it-again bias . An examination of Figure 14.2 reveals the treatment of Black executives and Indigenous Public Service employees reflects four of the biases identified: the prove-it-again bias, racial stereotype bias, the tug-of-war bias, and the tightrope bias.

Although Case Study 1 highlights the actions of those within Canada’s Public Service, there is a case to be made for the broad scale existence of the colonial worldview in business structures and systems across this country. Ironically, the case is made by the existence of equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) policies. As we will discuss, there would be no need for EDI policies and initiatives if current business systems and structures were not rooted in the colonial worldview.

Reader Reflection

Use the template below to plot the practices experienced or observed in a past or current workplace against the characteristics of the colonial worldview and the five patterns of everyday business biases.

EDI and the Colonial Worldview

Figures 14.1 and 14.2 reveal that the colonial worldview is alive and well in Canada’s largest employer. The harmful behaviours discussed in Case Study 1 demonstrate what scholars refer to as the the invisible, broadly accepted, and unchallenged existence of colonial values and beliefs (Decolonisation, 2023; Ermine, 2007; Sue, 2021; Sue et al., 2020) that continue to inform, influence, and affect everyday interactions. Ermine (2007) explains the phenomenon this way:

This notion of universality remains simmering, unchecked, enfolded as it is, in the subconscious of the masses and recreated from the archives of knowledge and systems, rules and values of colonialism that in turn wills into being the intellectual, political, economic, cultural, and social systems and institutions of this country (p. 198).

In the business context, policies introduced to remedy the adverse impacts of the colonial worldview are classified under the banner of EDI. Golden (2024) notes, the genesis of EDI policies is rooted in “a time when societal movements and legal changes began to reshape the corporate world” (para. 2) to balance recognized inequities in business structures and systems. Taking shape during the 1960s (Golden, 2024), initially EDI policies focused on redressing racial and gender inequality. However, by the 1990s, EDI policies “began to recognize and address the diverse needs of various identity groups, including ethnic, religious, and LGBTQ+ communities” (Golden, 2024, para. 11).

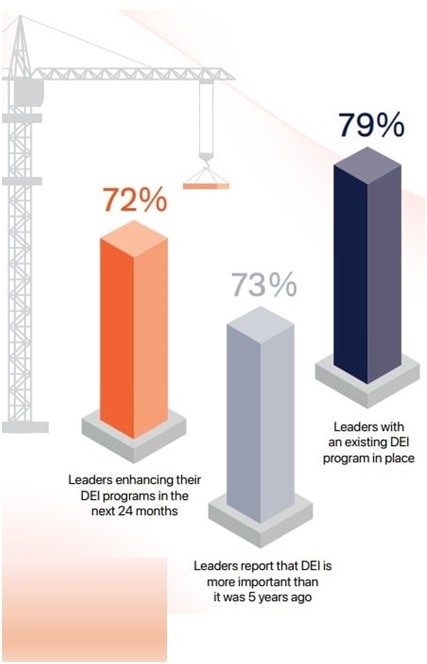

Today, 60+ years after the first EDI policies were introduced (Golden, 2024), as demonstrated by Case Study 1, the inequities that existed in business structures and systems are not yet balanced. In fact, several recent reports on the state of EDI in business reveal that, both domestically and internationally, businesses continue to support existing EDI policies and plan to increase their financial commitments to EDI policies in coming years as a strategy to address continued and ongoing inequities in the workplace (Benefits Canada, 2023; Carufel, 2024; Workday, 2024). The following statistics and Figure 14.3 illustrate this finding:

-

Figure 14.3 reveals the perspective of business leaders on the importance of EDI initiatives (Carufel, 2024). In 2023, 72% of Canadian business leaders increased financial support of EDI policies and initiatives (Benefits Canada, 2023).

- In 2024, a survey of 2,600 global business leaders found that 78% believed EDI policies had risen in importance and planned on increasing their organization’s EDI budget (Workday, 2024).

- In 2024, a survey of over 400 executives in mid-to-large U.S. companies reported that

- 79% of respondents confirmed the existence of EDI policies at their firm,

- 78% of respondents planned on increasing the support for EDI policies over the next two years, and

- 73% of respondents believed the importance of EDI policies had grown over the last five years.

(Carufel, 2024).

These statistics, among others, are an indication that the invisible and broadly accepted ideologies of the colonial worldview (Decolonisation, 2023; Ermine, 2007; Sue, 2021; Sue et al., 2020) are present in our modern workspaces. A problem that does not exist, does not need a solution. Workspaces that are diverse, equitable, and inclusive do not need EDI policies to balance the playing field. The continued and growing need of EDI policies confirms the broad scale influence of the colonial worldview in business systems and structures and the continued and growing need for strategies to counteract and temper that influence.

What can be done to decolonize ‘workplaces into spaces where knowledge is democratized, power is shared, and equity thrives” (Ebalaroza-Tunnell, 2024, para. 2)? The remainder of this Unit will examine this question from a structural and individual perspective.

Decolonizing Business Systems and Structures: An Indigenous Perspective

Can equity, diversity, and inclusion truly happen within business systems and structures founded on hierarchy, dominance, exploitation, and authority? Can a system meant to benefit some and not others create an inclusive playing field where everyone can thrive? Williams (2020) answers these questions with a resounding no: “To address structural [inequity], you need to change structures…we need to fix the business system” (1:10).

Changing society’s structures and systems will require a massive, intentional, and sustained ideological shift away from the established values and beliefs of the colonial worldview towards the values and beliefs of an alternative worldview. This ideological shift, at its essence, is the process of decolonization (Decolonisation, 2023). Ermine (2007) writes that in order “to redesign social systems[,] we need…[to] accept that a monoculture with a claim to one model of humanity and one model of society” (p. 198) is a fallacy. Such an ideological shift would reshape social systems to reflect the beliefs and values of the alternative worldview, and specifically for the purpose of this discussion, reshape business systems and structures in a similar manner.

According to Kouri-Towe and Martel-Perry (2024) decolonization can be examined through two alternative worldviews: the Indigenous and Afro-centric worldviews. In addition, decolonization can also be examined through a number of individual approaches, including gender equality, sexual equality, racial equality, and environmental equality. This Unit will examine the process and impacts of decolonization through the lens of the Indigenous worldview. The University of Alberta (n.d.) explains the Indigenous worldview this way:

Indigenous Ways of Knowing are based on the idea that individuals are trained to understand their environment according to teachings found in stories. These teachings are developed specifically to describe the collective lived experiences and date back thousands of years. The collective experience is made-up of thousands of individual experiences. And these experiences come directly from the land and help shape the codes of conduct for indigenous societies. A key principle is to live in balance and maintain peaceful internal and external relations. This is linked to the understanding that we are all connected to each other. The hierarchical structure of Western world views that places humans on the top of the pyramid does not exist. The interdependency with all things promotes a sense of responsibility and accountability. The people would respond to the ecological rhythms and patterns of the land in order to live in harmony. (00:30).

Continue learning about the Indigenous worldview and how it differs from the colonial worldview by viewing the full video, World View.

Rose (2021) suggests that in many ways, the Indigenous worldview offers an opposing philosophy on how to interact with and value the world we live in. The author offers that integral to the Indigenous worldview is the understanding that “all living things are connected…contribute to the circle of life equally and should be acknowledged and respected as such” (3:27). Review figure 14.4 for differences in characteristics between the Indigenous worldview to those of the colonial worldview.

Figure 14.4 illustrates quite a few differences in the belief and value systems of the colonial and Indigenous worldviews. Of note are

- a shift away from a singular worldview to a worldview that is inclusive of diverse experiences and voices,

- a shift away from superiority of some over others to equality and balance for all,

- a shift away from competition to collaboration and cooperation,

- a shift away from individualism to collectivism and community, and

- a shift away from exploiting resources to honouring and safeguarding them.

These shifts are not superficial. They suggest a fundamental rewiring of the way we think about and interact with each other and our environment. Central to our conversation is the possibility of applying the Indigenous worldview as a vehicle to decolonize the workplace. Let’s examine this possibility further.

Equality: The Indigenous worldview does not include a hierarchical structure that places one race over another, men over women, or humans over nature. Thus, the Indigenous worldview embedded with the philosophy of equality could create work environments that

- respect the skills and contributions of all employees equally,

- are stewards of the land, animals, and other natural resources, and

- welcome the skills and contribution of all employees at all levels of operation.

Variation: The Indigenous worldview acknowledges and welcomes the diversity that exists within humanity. The Indigenous worldview embedded with the philosophy of variation could result in work environments that promote

- innovative, collaborative, and democratic, and

- empathetic, supportive, and inclusive

Community/interconnectedness: Being in good relations with your community is at the heart of the Indigenous worldview (Rose, 2021). A work culture embedded with this value could result in work environments that

- do not exploit workers,

- ensure a basic living wage,

- provide safe work environments,

- support a work-life balance, and

- employ sustainable business practices.

Reader Reflection

The list presented above is not exhaustive as the Indigenous worldview would result in many other changes to work environments. Share your thoughts on what other changes you believe would result from the establishment of the Indigenous worldview in the workplace.

Another measure by which the Indigenous worldview can be assessed to evaluate its potential to decolonize the systems and structures that make up our work environment is the degree to which it avoids or prevents the five patterns of biases experienced in everyday business interactions (Williams, 2020). Table 14.1 presents each bias, its description, and how the Indigenous worldview is likely to impact their occurrence in the workplace.

Table 14.1: How Indigenous Worldview Can Change Five Types of Bias

EDI and the Indigenous Worldview

An important observation when reviewing the potential results of implementing the Indigenous worldview in business structures and systems is the organic occurrence of behaviours and practices that are typically considered the outcome of EDI policies and initiatives. Aspects of equity, diversity, and inclusion are not planned, legislated, or imposed under the Indigenous worldview. Instead, practices that are currently the result of EDI policies naturally occur, directly connect, and are enmeshed with the Indigenous worldview.

The possibilities above of an alternative way of doing and thinking in the many workspaces across this country is not imagery or hypothetical. Work environments that reflect the principles of the Indigenous worldview already exist. The following case study of Sanala Planning, an Indigenous owned and run business, is one example of the Indigenous worldview in action.

Case Study 2: Sanala Planning

Originally Alderhill Planning, Sanala Planning is based in Kamloops, BC. and is owned and run by Jessie Hemphill, a member of the Sqilxw People (Sanala, n.d.). Founded in 2016, the company’s mandate is to “work with governments, businesses and First Nations communities to support organizational development, providing everything from trauma-informed facilitation to comprehensive community plans, to workshops on reconciliation and decolonization” (Kilawna, 2022, para. 4). Through community consultations, a bottom-up approach was utilized to ensure the company’s business plan, mission, and activities aligned with the needs and wants of the communities served by the organization.

A first business practice to be highlighted here is one that is not typically associated with the business environment: empathy. Hemphill says this trait contributes to “a really safe [and] nurturing place to work” (Kilawna, 2022, para. 30). Allowing staff members to breast feed during Zoom meetings, designating office space for spiritual practice, and giving employees the flexibility to openly acknowledge and share mental health challenges (Kilawna, 2022) are some of practices that support this trait. Other alternative business practices employed by Sanala Planning include

- a non-hierarchical and inclusive decision-making process with employees,

- a shortened work week (4 days/week), and

- reduced daily work hours.

(Kilawna, 2022).

Many aspects of the Indigenous worldview can be observed in the creation and day-to-day business practices of Sanala Planning: community engagement, collaboration, work-life balance, empathy, and a democratic power structure. Of significance is the understanding that these practices have not undermined Salana Planning’s ability to be financially successful. According to Kilawna (2022), Sanala Planning has a market value of $2 million.

Although, businesses like Sanala Planning exist, businesses established to reflect the Indigenous worldview are not commonplace. However, opportunity exists to integrate Indigenous values and beliefs into business systems and structures. Ermine (2007), Fielding News (2022), and Egale Canada (2024) offer the following strategies to accomplish this goal:

- Do your research to continue learning the histories, teachings, practices, beliefs and values of Indigenous Peoples.

- Challenge your own understanding and acceptance of current business systems and structures. Do the hard work necessary to bring to light many of the unchallenged values and beliefs that form the basis of current business systems and structures.

- Advocate for the Indigenization of workplace practices by using your knowledge of the Indigenous worldview to promote an ideological shift in workplace practices.

- Promote the establishment of physical spaces that create communal connection and spiritual awareness.

Reader Reflection

Compare the business practices of Sanala Planning to an organization/business that you currently work for or previously worked for. Reflect on the differences and similarities between the two organizations. How do you think these differences and similarities affect or affected the work environment?

Decolonizing Organizational Structure: Individual Action

Systemic and structural change in the workplace will undoubtedly take time. In the meantime, there is much you can do on an individual level to decolonize your current and future work environments for all equity seeking groups.

1. Allyship

The concept of allyship was introduced in Unit 11: Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion: Terminology. There, an ally is defined as a person who supports equity seeking persons or groups through action by interrupting behaviours and situations counter to fairness and equality (para. 34). Working with this definition, Ravishankar (2023) offers the following strategies to help recognize and disrupt patterns of inequity in the workspace:

- Learn about the stereotypes, experiences, and identities of the marginalized group you would like to support. Here the author suggests contacting different organizations that advocate for the rights of marginalized groups. If you are interested in supporting one particular group or notice specific harmful behaviours in your workplace that you would like to address, speak directly to those affected to understand how best to lend your support.

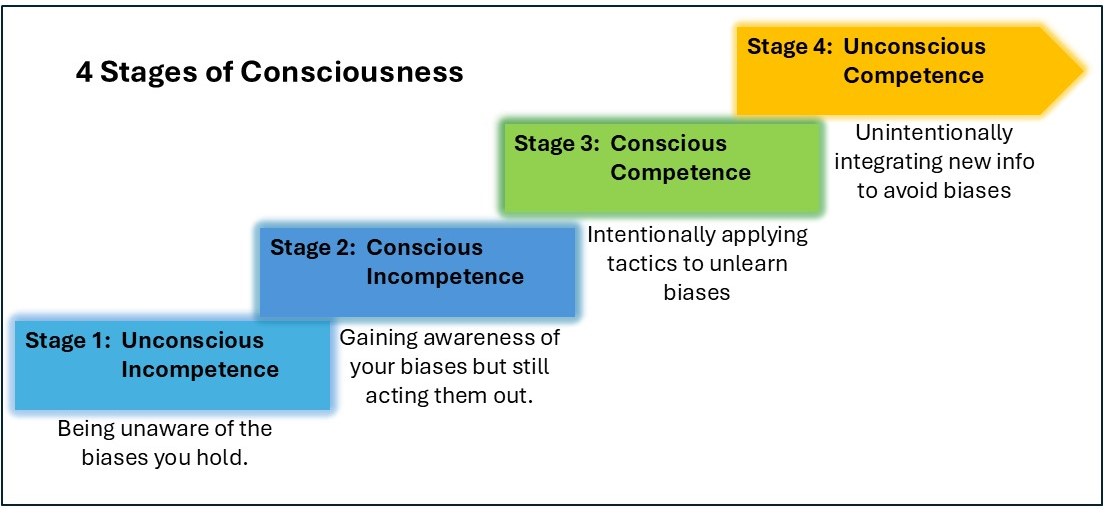

- Unlearn your own personal biases. We all carry some biases, many of which may be unconscious. Biases are products of our worldview. Reflect on your own behaviours and thoughts to make the unconscious, conscious. When you better understand the bias you hold, you can address them and begin your journey towards allyship. Review Figure 14.5 for a model of how to work your way from being unaware of your own biases towards conscious awareness and action.

- Voice your opposition to instances of microaggressions, discrimination, racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, etc. when you witness these behaviours in the work environment. The author notes that saying something “as simple as “Not cool,” or “That’s not funny”” (para. 17) is suitable when you encounter such behaviours at work.

- Model the behaviour you would like to see in your workplace. By treating people appropriately, you can provide an example for others of how to interact respectfully with diverse members or your work environment. The author suggests that the use of inclusive language (see Unit 29) is one way to model behaviour of how to treat others respectfully.

The publication, Skoden (2022), includes the Ally Bill of Responsibilities developed by Dr. Lynn Gehl. Developed from an Indigenous perspective, the Ally Bill of Responsibilities provides an extensive list of what it means to be a responsible ally.

2. Be Curious, Take Accountability, and Unlearn to Relearn

In the TedX Talk, Deconlonizing the Workforce (2024), the speaker, Toni Lowe, offers three tactics that can further help decolonize the workforce.

Strategy 1: Be curious. Lowe (2024) offers that when certain dynamics occur in the workplace, you have a responsibility to investigate the reason for the observed behaviour, thought, or action. For example, Case Study 1 revealed that Indigenous Public Service employees were asked to complete IQ tests that non-Indigenous employees were not (Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation, 2017). Thus, when similar situations occur in your workplace, Lowe (2024) encourages you to become curious and ask questions like:

- What is happening?

- Why is this happening?

- What belief forms the basis for this action?

- Do I believe this?

- Is this true?

- What else do I believe that may not be true?

The answers to questions like these, the author suggests, may lead to a new awareness of inequities in your work environment.

Step 2: Take accountability. Reflect on your role in the current system. Consider if your “silence, complacency, or advantage” (Lowe, 2024) props-up or confronts the status quo. The author explains that reflecting on your role in the system is the first step towards taking accountability for your actions or inactions, acknowledging the lived experience of racialized and marginalized groups, and embracing your power to influence your environment.

Step 3: Unlearn to Re-learn. In agreement with Ravishankar (2023), Lowe (2024) also imparts the importance of recognizing and addressing unconscious biases. The author argues that in doing so, you will be able to clearly see your choice to stop participating in and supporting an outdated worldview that no longer makes sense for a modern world (Lowe, 2024).

3. Believe Lived Experiences. A simple but effective strategy to decolonize the workplace is based on a study on the effects of microaggression in the work environment. Sue (2021) concludes that an important aspect of decolonizing the work environment is for members of dominant groups to acknowledge and believe the lived experiences of maltreatment endured by racialized and marginalized colleagues. Although, the experience of racialized and marginalized groups is often very different from the experience of members of the dominant groups in the same work environment, the author encourages members of dominant groups to not ignore, deny, doubt, discredit, or minimize these lived experiences (Sue, 2021). Instead, Sue et al. (2019) directs individuals to

- Reaffirm and validate the lived experience of racialized and marginalized groups by believing their experiences,

- Be vocal and visible in your support for the fair treatment of every employee,

- Be vocal and visible in your opposition to the maltreatment of any employee, and

- Seek support from and mobilize with like minded employees to develop better workplace practices and policies.

Reader Reflection

- Which of the individual decolonizing strategies above are you most comfortable integrating into your current and/or future workplace? Explain why.

- Can you think of other strategies that could also decolonize the workplace.

Colonialism and the colonial worldview are not issues of the past. Instead, the colonial worldview continues to affect all aspect of Canadian society, including our workspaces. The review of the practices within the Canadian Public Service demonstrated the colonial worldview at work by revealing discriminatory, racist, hostile and exclusionary treatment of Black and Indigenous employees. Such actions, however, are not confined to the Canadian Public Service. Instead, the continued existence and growing importance of EDI policies in our workspaces indicates the presence of continued inequities towards racialized and marginalized groups. A strategy to decolonize the workplace at the structural and systemic level was offered via the Indigenous worldview. Here, we saw that the Indigenous worldview provides an alternative to the recognized imbalances in current business structures and systems because of its capacity to create workspaces that organically reflect the principles of EDI. The example of Sanala Planning is offered as an illustration of the potential of the Indigenous worldview to create successful and financially profitable work environments. At the individual level, the Unit ends by speaking directly to you, the reader, whose role is central in creating decolonized workspaces. By adapting the individual actions discussed above, you can become agents of change in “paving a way for a workforce where everyone can thrive” (Lowe, 2024, 14:11).

References

Benefits Canada. (2023). 72% of business leaders increased investment in DEI over past year: survey. News. https://www.benefitscanada.com/news/bencan/72-of-business-leaders-increased-investment-in-dei-over-past-year-survey/

Beebe, S., Beebe, S., Ivy, D., & Watson, S. (2005). Communication principles for a lifetime (Canadian Edition). Pearson.

Carufel, R. (2024). Despite a year of attacks and criticism, business leaders continue to support DEI initiatives: New research examines DEI progress and today’s challenges. Agility PR solutions. Despite a year of attacks and criticism, business leaders continue to support DEI initiatives: New research examines DEI progress and today’s challenges – Agility PR Solutions

CGSMUS. (2023). Decolonisation [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Km_TmRuk7Q

Doerr, A. (2013). Public service. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/public-service

Ebalaroza-Tunnell, G. (2024). Decolonizing the workplace: Building a more equitable future. Medium. https://medium.com/@DrGerryEbalarozaTunnell/decolonizing-the-workplace-building-a-more-equitable-future-87022f903187

Egale Canada. (2024). Indigenous workbook. Building bridges. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://egale.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/2.-Indigenization-Workbook_Final.pdf

Ermine, W. (2007). The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal 6(1). https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ilj/issue/view/1822

Fielding News. (2022). Why making vital distinctions between Indigenous and dominant worldviews is not a “binary thinking problem”. Fielding Graduate University. https://www.fielding.edu/making-vital-distinctions-between-indigenous-and-dominant-worldviews/

Golden, H. (2024). History of DEI: The evolution of diversity training programs – NDNU. Notre Dame de Namur University. https://www.ndnu.edu/history-of-dei-the-evolution-of-diversity-training-programs/

Government of Canada. (2017). Many voices one mind: A pathway to reconciliation. https://www.canada.ca/en/government/publicservice/wellness-inclusion-diversity-public-service/diversity-inclusion-public-service/knowledge-circle/many-voices.html#toc7

Indigenous Canada. (n.d.). World View. University of Alberta. https://www.coursera.org/lecture/indigenous-canada/indigenous-worldviews-xQwnm

Indigenous Corporate Training, Inc. (2016). Indigenous worldview vs. western worldview. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/indigenous-worldviews-vs-western-worldviews

Kilawna, K. (2022). Meet the sqilxw women who are decolonizing the workplace. IndigiNews. https://indiginews.com/features/elaine-alec-shares-what-it-means-to-decolonize-the-workplace?gad_source=1&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI_8HK2e-BiQMVBDYIBR2UfDUEEAAYAyAAEgLUh_D_BwE

Kouri-Towe, N., & Martel-Perry, M. (2024). Better practices in the classroom. Concordia University. https://opentextbooks.concordia.ca/teachingresource/

Potter, R., & Hylton. T. (2019). Intercultural relations. Technical writing essentials. https://pressbooks.senecapolytechnic.ca/technicalwriting/wp-admin/post.php?post=2253&action=edit

Public Service Alliance of Canada. (2024). Shocking internal report exposes rampant discrimination at the head of Canada’s public service. https://psacunion.ca/shocking-internal-report-exposes-rampant

Ravishankar, R. A. (2023). A guide to becoming a better ally. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2023/06/a-guide-to-becoming-a-better-ally

Rose, M. (2021). Indigenous worldview: What is it, and how it is different [Video]? Youtube . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4KzqMMYatc4

Sanala. (n.d.). salana.com. https://www.sanalaplanning.com/

Skoden. (2022). Teaching, talking, and sharing about and for reconciliation. Seneca College. Skoden – Simple Book Publishing

Sue, D. W. (2021). Microaggressions and the “lived experience” of marginality. Division 45. https://division45.org/microaggressions-and-the-lived-experience-of-marginality/

Sue, D. W., Calle, C. Z., Mendez, N., Alsaidi, S., Glaeser, E. (2020). Microintervention strategies: What you can do to disarm and dismantle individual and systemic racism and bias. https://www.google.ca/books/edition/Microintervention_Strategies/GaIQEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA1&printsec=frontcover.

TedxTalks. (2024). Decolonizing the workplace [Video]. TedxFrisco. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lg7fMbN1MjI

Thurton, D. (2024). Internal report describes a ‘cesspool of racism’ in the federal public service. CBCNews. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/racism-federal-public-service-black-1.7378963

United Nations. (2023). Summary of the panel discussion on the negative impact of the legacies of colonialism on the enjoyment of human rights. General Assembly. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/sessions-regular/session54/A_HRC_54_4_accessible.pdf

Unit Nations (n.d.). Racism, discrimination are legacies of colonialism. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/get-involved/stories/racism-discrimination-are-legacies-colonialism#:~:text=Cal%C3%AD%20Tzay%20added%20that%20the,of%20language%20and%20culture%2C%20and

Wilson, K., & Hodgson, C. (2018). Colonization. Pulling Together: Foundations Guide. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationfoundations/chapter/colonization/

Williams, J. (2020). Why corporate diversity programs fail and why small tweaks can have big impacts [Video]. TedxMileHigh. https://www.ted.com/talks/joan_c_williams_why_corporate_diversity_programs_fail_and_how_small_tweaks_can_have_big_impact

Williams, J. C., & Mihaylo, S. (2019). How the best bosses interrupt biases on their teams. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/11/how-the-best-bosses-interrupt-bias-on-their-teams

Workday. (2024). Workday DEI landscape report: Business leaders remain committed in 2024. Human Resources. https://blog.workday.com/en-us/workday-dei-landscape-report-business-leaders-remain-committed-2024.html#:~:text=While%20DEI%20faced%20challenges%20in,of%2011%25%20compared%20to%20last

A narrower range of behaviors is accepted from some groups than from others.

Women with children see their commitment and competence questioned or face disapproval for being too career focused.

Being limited by preconceived notions of expected performance, behaviour, potential, and acumen associated with a specific race.

Disadvantaged groups find themselves pitted against one another because of lack or resources and opportunity.

Some groups have to prove themselves more than others do to establish their competence or justify their position.

Policies aimed at creating work environments that support diversity, equity, and inclusion of marginalized, racialized, and equity seeking groups, thoughts, and experiences.