9 Reasons Not to Believe

Steven Steyl

Introduction

Arguments against God, religious belief, and the supernatural have long attracted the attention of philosophers. Atheism, as a socially viable, seriously considered alternative to theism, has taken root only in the last few centuries, but many arguments now associated with atheism have been debated in philosophical circles for much longer—not in the form of proofs of God’s non-existence, but more often in the form of concerns that any adequate belief set must resolve. In this chapter, we shall examine some of the most prominent arguments against theistic belief.

Theism, of course, encompasses a multitude of belief sets, ranging from monotheistic religions such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, to polytheistic religions such Hinduism and (arguably) Buddhism, and even pantheism, so it will be necessary to limit our scope somewhat. Philosophical arguments against theism normally target a specific subcategory of monotheism typified by the Abrahamic traditions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam). This brand of monotheism worships what some philosophers of religion call the “omniGod,” a god possessing the following omni-properties:

- omniscience, or knowledge of everything;

- omnipotence, or the power to do anything; and

- omnibenevolence, or perfect (moral) goodness.

Other gods may, of course, possess some combination of these, but critiques of theism tend to aim explicitly at the versions of the omniGod in these three traditions, so this form of monotheism shall be our focus.

The omniGod is usually viewed through the lens of personalism, the claim that God is a person of some sort. Personalists are not committed to the claim that God is an embodied person, as though God had a genetic makeup, a spleen, and so forth. Rather, theistic personalists conceive of God as responsive or reflective in ways akin to our own. God has, for instance, emotional responses to worldly events much like we do. Personalism, however, is not the only option for omniGod theists. Classical theists like St. Augustine (354-430) and St. Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274) had a very different, non-personal concept of God. According to classical theism, God is simple, so that all of their properties are identical to one another and also to God (God’s benevolence is their timelessness, and God is God’s benevolence); immutable, so that their properties cannot change; impassible, unable to be acted upon by us or anything in the causal world; and timeless, existing outside of time.[1] But here we shall be dealing primarily with the personalist omniGod, since it (a) is a more popular conception of God among philosophers, and is therefore the subject of most attempts to discredit theism, and (b) is more familiar to theists today.

The Incoherence of Divine Attributes

Philosophers have been thinking about God’s properties for millennia. One popular argument against this concept of God also arises from such reflection. It maintains that the omni-properties are either internally or externally incoherent, and therefore a god which possesses these traits cannot possibly exist.

Omnipotence, as defined above, is a common target for such arguments, because it seems to lead to paradoxes. These paradoxes usually have to do with God’s ability to restrict their own power. Can God create a stone that is too heavy for them to lift? Can God create something indestructible, so that it cannot be later destroyed by its maker? If the answer to either question is “yes,” then there are some things that God cannot do. If God can create an object that cannot be destroyed by its maker, then they cannot destroy that object, and the same is true, mutatis mutandis (that is, with the necessary changes), for a rock that they cannot lift. On the other hand, if the answer to either question is “no,” and God is incapable of limiting themself in this way, then again there are some things God cannot do. So omnipotence, defined as an ability to do anything at all, cannot be one of God’s (or any being’s) traits, since the very concept of omnipotence is internally inconsistent.

There are a number of responses available to the defender of divine omnipotence. One is to suggest, as René Descartes (1596-1650) does, that God can in fact create a stone that is too heavy for them to lift, but that this is not problematic because God is not bound by the laws of logic or similar metaphysical truths. We suppose that it is contradictory for a human being, who cannot perform logically impossible feats, to create a rock that is too heavy for her to lift. But why think that God, the Almighty, would be bound by similar laws? If we believe that God is all-powerful, then they could well be capable of suspending the laws of logic!

Such solutions raise other problems, however. One might reasonably ask, in response to this answer, whether such a god can be reasoned about at all.[2] There are, after all, certain claims about God that theists will typically want to make. And it seems that many of those claims are only tenable because they are logical. Consider, for example, omnibenevolence. If God is omnibenevolent, we know that they always do what is good. But if God is not constrained by the laws of logic, then we have no reason to accept this statement. God’s omnibenevolence only entails morally good actions because it follows logically. So theists who defend omnipotence by claiming that God is in some sense beyond logic may be throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Another option is to concede that the definition of omnipotence above ought to be revised. One could, for example, qualify the above definition by appending “except that which is logically impossible,” without deviating too radically from our original conception of God as all-powerful. Though we have shelved his concept of God, we might still like to borrow an idea from Thomas Aquinas, a prominent Medieval philosopher and theologian, who defended such a view:

since power is said in reference to possible things, this phrase, “God can do all things,” is rightly understood to mean that God can do all things that are possible; and for this reason He is said to be omnipotent. (Summa Theologiae, Ia, 25, 3)[3]

Such a manoeuvre is not without its hazards, of course. One might think that such a God fails to satisfy conditions of adequacy for an object of worship, appealing perhaps to an Anselmian view that God is that “than which no greater can be thought.”[4] It is, nevertheless, open to the omniGod theist to either challenge the supposed inconsistency, or to revise their account of omnipotence.

Another problem arises when we question whether the omni-properties are consistent or coherent with one another. One could claim that any of the traits mentioned above is internally consistent and non-paradoxical, but that the set of traits attributed to God generates contradictions and cannot therefore be possessed by a single entity. Consider the following premise:

- Omniscience interferes with free will.

If we take omniscience to include infallible knowledge of every future event, then God knows with absolute certainty that they will do x at a given time t.[5] If this is true, then it looks as though omniscience interferes with free will. But if omniscience interferes with free will, then it looks as though omniscience also interferes with omnipotence. If God cannot be mistaken about how they will act at t, then God is incapable of doing anything other than x. Thus, we arrive at:

- If God lacks free will, then God lacks omnipotence.

And omniscience may also conflict with omnibenevolence. The freedom to do otherwise is often thought of as a precondition for morally good action (I am not performing a praiseworthy action if a mind control device forces me to rescue a drowning child). Yet if God infallibly knows how they will act and thus cannot act otherwise, then one could plausibly argue that there seems to be a similar lack of moral freedom with respect to their actions. So it appears as though omnibenevolence is inconsistent with omniscience, and we can add the following premise to the argument:

- If God lacks free will, then God lacks omnibenevolence.

If these premises are all true, omniscience interferes with free will, and as a result it interferes with both omnipotence and omnibenevolence. The argument would thus reach the following conclusion:

- If God is omniscient, God cannot be omnipotent (2) or omnibenevolent (3).

And notice that one could present a different argument that begins with either omnibenevolence or omnipotence, and goes on to claim that either of these properties is inconsistent with the others. Consider:

- 1*. Omnibenevolence seems to interfere with free will

- 2. If God lacks free will, then God lacks omnipotence.

If omnibenevolence amounts to moral perfection, then we can infer that God necessarily does what is morally best in any given scenario. But this is just to say that God cannot do anything that is morally suboptimal. God cannot, therefore, be omnipotent if we take omnipotence to mean an ability to perform morally imperfect actions.

So it appears as though all of the omni-properties can be brought into prima facie conflict (that is, into conflict at first glance) with any of the others. If any of these inconsistencies hold water, then once again, the omniGod cannot exist, because in order to exist, they must possess a set of traits that are logically inconsistent with one another.

Questions to Consider

- Do you think that God can suspend the laws of logic and bring about contradictions? Why or why not?

- Select one of the apparent inconsistencies between two omni-properties and respond to that apparent inconsistency on the omniGod theist’s behalf.

- Is it open to the theist to abandon one or more omni-properties altogether? Can you think of reasons for them not to do so?

Problems of Evil

The omni-properties may be inconsistent not only with each other, but with observable or indispensable facts about the world. In this subsection we shall look at the apparent inconsistency between the omni-properties and the existence of evil. Take the following example:

Suppose in some distant forest lightning strikes a dead tree, resulting in a forest fire. In the fire a fawn is trapped, horribly burned, and lies in terrible agony for several days before death relieves its suffering. (Rowe 1979, 337)

For many philosophers, and many reflective non-philosophers, it is difficult to reconcile the existence of such evils in the world with belief in an omniGod. How could an almighty creator, who brims with loving-kindness, allow any evil to exist in the world, let alone evils of the scale and severity we see in the world today? This apparent tension between the existence of evil and the existence of the omniGod has birthed a number of arguments from evil, designed to show that belief in God is at best unreasonable and at worst outright irrational. Here, we shall focus on moral evils, evils for which some agent is morally responsible or blameworthy. As we shall see at the end of this section, other evils must also be dealt with.

Of those arguments, J. L. Mackie’s argument from evil has been by far the most influential. Mackie argued that belief in the omniGod is irrational because evil could not coexist with a God who possesses two of the omni-properties above. On Mackie’s view, the inconsistency emerges once we begin to flesh out each of omnipotence and omnibenevolence:

- If God is omnipotent, there are “no limits to what [they] can do” (Mackie 1955, 201).

- If God is omnibenevolent, they are “opposed to evil, in such a way that [they] always eliminate[ ] evil as far as [they] can” (Mackie 1955, 201).

Together, premises (1) and (2) suggest that if the omniGod existed, evil would not.[6] The omniGod of Abrahamic theology is perfectly able and entirely willing to eliminate all of the world’s troubles. But it is quite clear, Mackie insists, that evil does exist. The upshot of Mackie’s argument, then, is that if evil exists (and it certainly seems to) then God is either not omnipotent or not perfectly good. In other words, the omniGod does not exist. David Hume articulates this position more forcefully in an oft-quoted passage from his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (Hume 1948): “is [God] willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Whence then is evil?”[7]

One of the most renowned responses to such problems of evil, defended by philosophers like Plantinga (1974), is known as the free will defence. The free will defence begins with an intuitively plausible premise: free will is very valuable and ought to be preserved. More specifically, the free will defence begins by noting the import of libertarian free will, a capacity to choose your own actions without being caused to act by anything external (e.g. a mind control device or being held at gunpoint). A person exercises libertarian free will whenever their actions are not brought about by outside interference. But this sort of free will therefore requires God’s non-interference. God cannot force us to act in certain ways without thereby sacrificing libertarian free will. So they cannot coerce us into morally upstanding actions without eliminating something of great value. The crux of the free will defence is thus a dilemma. God must choose either to allow us our libertarian free will and in doing so run the risk that we will sometimes act reprehensibly, or to intercede in human life, preventing us from causing evil, but at the cost of our libertarian free will.[8] Despite possessing the omni-properties, God is faced with forced choices in much the same way we are, and it is better (or more modestly, it could be better for all we know) that God leaves our free will intact.

Many theists find this response satisfying, and it is certainly an elegant solution. But it is a solution which resolves only part of the problem. The free will defence makes sense of evils like murder and theft, which are freely chosen. But some evils seem to have nothing to do with free will at all. More specifically, some philosophers have argued that the free will defence cannot explain natural evils, evils for which no agent is morally responsible or blameworthy—like volcanic eruptions, forest fires, and tsunamis. How, after all, can Rowe’s example above be explained by reference to free will? There is no discernible libertarian free will on which to lay blame there, since such evils are caused by natural processes. So we might think that the free will defence yields only a partial solution to the problem of evil, and that there are other cases of evil which require other solutions.

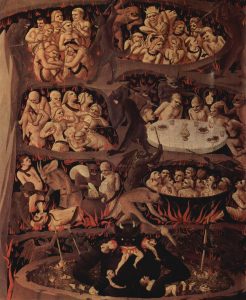

The Problem of Hell

Hell comes in many forms, but whether one conceives of hell as an eternal state of “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matthew 13:42), or a state of unrepentant debauchery and wickedness, hell is universally seen as an evil of the worst order, and it thus raises an acute problem of evil. The problem is also exacerbated by hell’s finality, since it is often thought to be eternal or infinite, and by its direct administration (or at least explicit permission) by God. For some omniGod theists, another aggravating factor also holds true: some non-believers are consigned to hell for committing no special sin other than non-belief. Philosophers of religion are rightly concerned about the philosophical defensibility of such accounts of hell, and many have for that reason embraced a universalist eschatology—that is, a view on which every person, regardless of their beliefs, character, or actions in this life, eventually reaches heaven.

Questions to Consider

- Are you convinced by Mackie’s problem of evil? Why or why not?

- In order for the free will defence to succeed, it will need to provide good reasons for thinking that libertarian free will is of greater value than the prevention of evil. Does this seem plausible? Why or why not?

- Do you think the free will defence can explain natural evils like earthquakes and volcanoes? Why or why not?

- How can God’s omnibenevolence be reconciled with the existence of hell? Are theists forced to be universalists about heaven?

Divine Hiddenness

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from saving me, so far from my cries of anguish? My God, I cry out by day, but you do not answer, by night, but I find no rest (Psalm 22:1-2 [NIV]).

It is also peculiar that the omniGod, who loves us infinitely and who so strongly desires for that love to be reciprocated, is entirely hidden from many of us. This apparent absence from the world gives rise to a cluster of objections to omniGod theism. Which subspecies pertains depends in part on what exactly we mean by “hidden.” In the passage from the Book of Psalms quoted above, God is hidden from a believer in such a way that they sink into a sort of existential crisis. God’s existence is not hidden, since the Psalmist is not questioning whether God exists or not. Rather, the Psalmist is puzzled and upset by God’s failure to interact. So Psalm 22 raises a problem of what one might call divine withdrawal. An objection from divine hiddenness could also adopt a different tack and say that God’s existence is discoverable, but that their nature or their plans are hidden from us in some problematic way, in which case we might prefer to call our problem one of divine mysteriousness. Here, however, we shall focus on moral and epistemological problems raised by divine hiddenness in a different sense. We shall examine divine hiddenness in the context of non-resistant non-belief, where God has not made their existence sufficiently perceptible to non-believers.

John Schellenberg is perhaps the most well-known proponent of this argument from divine hiddenness, and his argument in Divine Hiddenness and Human Reason (1993) is widely recognized as the first modern statement of the problem. In this subsection we shall reconstruct that argument, taking on board some of the revisions he has made since it was published. Schellenberg’s argument, in essence, is that the existence of an omnibenevolent God is inconsistent with the existence of non-resistant non-believers. A perfectly loving God would not allow for non-resistant non-belief, because belief constitutes a precondition for personal relationship.

What do we mean by “non-resistance” here? Schellenberg himself has not always used that term. Indeed, he initially preferred the language of culpability, and this does perhaps shed some light on what he means. Schellenberg also offers several illustrative examples of resistance:

We might imagine a resister wanting to do her own thing without considering God’s view of the matter, or wanting to do something she regards as in fact contrary to the values cultivated in a relationship with God … imagine careless investigation of one sort or another in relation to the existence of God, or someone deliberately consorting with people who carelessly fail to believe in God and avoiding those who believe, or just over time mentally drifting, with her own acquiescence, away from any place where she could convincingly be met by evidence of God. (Schellenberg 2015b, 55-56)

Resistance thus involves “actions or omissions (at least mental ones)” which “shut the door” to a relationship with God. One cannot be ignorant of the fact that one is resisting, so there is some element of intention in resistant non-belief, specifically an intent to end or diminish or preclude belief in God. Non-resistant non-belief, on the other hand, means non-belief in God where the non-believer has not “shut the door”—where, for example, some trauma or major life-event has preempted belief, or where someone has never come across the concept of God.

Schellenberg begins his argument for the incompatibility of God’s existence and non-resistant non-belief with the following thought:

- If a perfectly loving God exists, then they are always open to a personal relationship with any person capable of entering into one.

Openness, here, means nothing more than being willing to enter into a relationship. It does not mean that God is or ought to be actively pursuing a relationship with every one of us, or that we cannot choose to spurn them. It means simply that God is not actively ruling out a relationship with any person. Unless you yourself have rejected God, there is nothing to stop you from participating in a relationship with them. Schellenberg goes on to add another premise to his argument:

- If there is a God who is always open to a personal relationship with any person, then no person is ever non-resistantly in a state of non-belief about God’s existence.

This premise says just that God’s openness to a relationship with us rules out non-resistant non-belief. In order to be in any sort of loving relationship with another person, you must first believe that they exist. So in order for you to be open to a relationship with God, you must accept that he or she exists. Thus, an omniGod would guarantee that you are always capable of relation by ensuring that you always believe in their existence. Schellenberg explains:

by not revealing his existence [God] is doing something that makes it impossible for [the non-resistant non-believer] to participate in personal relationship with [God] at the relevant time even should she try to do so, and this … is precisely what is involved in [God’s] not being open to having such a relationship with [non-resistant non-believers]. (Schellenberg 2015a, 23)

Schellenberg’s argument, then, is that a perfectly loving (i.e. omnibenevolent) God would always be open to a personal relationship with those whom they love, and would always take steps to maintain the possibility of such a relationship even if it never comes to fruition. A necessary precondition for any personal relationship is that each participant believes the other exists. So in order for a personal relationship to be possible, God would make their existence known. Yet, Schellenberg continues, God has not made their existence known.[9] Non-resistant non-believers do exist, and therefore the omniGod does not.

Responses to this problem have often consisted in pointing out reasons why God might choose to remain hidden. Daniel Howard-Snyder, a prominent commentator, has argued that a non-believer’s justifications for non-resistance could supply God with a good reason for remaining hidden. It seems reasonable, Howard-Snyder argues, to suggest that some motives for non-resistance are improper, and the omniGod could choose to remain hidden from such a believer until they adopt better reasons for being non-resistant. Consider someone who is non-resistant, but only because he or she wants to avoid damnation and spend eternity in bliss.[10] The motive for non-resistance, in such a case, is pure self-interest. Yet we can envision an omniGod deciding to remain hidden from such a person until they have better reasons for being non-resistant, and this does not seem, at first glance, as though it is morally wrong. So perhaps God’s hiddenness is not proof of their non-existence.

Questions to Consider

- Is the problem of divine hiddenness a version of the problem of evil? Why or why not?

- Does Schellenberg’s exposition of divine love seem reasonable to you? Can you think of everyday examples of, or counterexamples to, his account of perfect love?

- Can you think of other reasons why God might choose to remain hidden from non-resistant non-believers? Do you think, for instance, that there is something valuable about freely choosing to believe in God without their revealing themself? Is this the kind of free choice an omnibenevolent God would pursue? Consider our discussion of free will in Section 3.

- Do you think the problem of hiddenness exacerbates the problem of hell? Does it conflict even more with omnibenevolence to both (a) put people into hell for non-belief and (b) remain hidden?

References

-

Aquinas, Thomas. (ca. 1265-1274) 1912-1936. Summa Theologiae. Trans. English Dominican Fathers. London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne.

Aquinas, Thomas. (ca. 1258-1264) 1934. Summa Contra Gentiles. Trans. English Dominican Fathers. London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne.

Augustine. (ca. 413-426) 2013. The City of God, Part II. Trans. William Babcock. Hyde Park, New York: New City Press.

Descartes, René. (1641) 1911. Meditations on First Philosophy. In The Philosophical Works of Descartes. Trans. Elizabeth Haldane. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hume, David. (1779) 1948. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. New York: Hafner.

Mackie, J. L. 1962. Truth, Probability, and Paradox. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mackie, J. L. 1955. “Evil and Omnipotence.” Mind 64(254): 200-212.

Plantinga, Alvin. 1974. God, Freedom, and Evil. New York: Harper and Row.

Rowe, William. 1979. “The Problem of Evil and Some Varieties of Atheism.” American Philosophical Quarterly 16(4): 335-341.

Schellenberg, John. 1993. Divine Hiddenness and Human Reason. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Schellenberg, John. 2015a. “Divine Hiddenness and Human Philosophy.” In Hidden Divinity and Religious Belief: New Perspectives, Adam Green and Eleonore Stump eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schellenberg, John. 2015b. The Hiddenness Argument: Philosophy’s New Challenge to Belief in God. New York: Oxford University Press.

Further Reading

Textbooks

Some excellent entry points into the discourse are:

Burns, Elizabeth. 2017. What is This Thing Called Philosophy of Religion? New York: Routledge.

Clack, Beverly and Brian Clack, eds. 2019. The Philosophy of Religion: A Critical Introduction. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Polity.

Davies, Brian. 2004. An Introduction to Philosophy of Religion. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meister, Chad. 2009. Introducing Philosophy of Religion. Abingdon, Routledge.

Online Resources

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, a reputable and free online resource covering a variety of philosophical topics. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, a free online resource which also covers select topics in philosophy. Consider also Crash Course Philosophy, a Youtube series dealing with a number of philosophical topics.

- Crash Course Philosophy

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Miracles

Readings Specific to Each Topic

Internal/External Inconsistency of Divine Properties

Adams, Sarah. 2015. “A New Paradox of Omnipotence.” Philosophia 43(3): 759-785.

Hoffman, Joshua. 1979. “Can God Do Evil?” Southern Journal of Philosophy 17(2): 213-220.

Hoffman, Joshua and Gary Rosenkrantz. 2002. “Omnipotence.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/omnipotence/

La Croix, Richard. 1973. “The Incompatibility of Omniscience and Omnipotence.” Analysis 33(5): 176.

Pike, Nelson. 1969. “Omnipotence and God’s Ability to Sin.” American Philosophical Quarterly 6(3): 208-216.

Rowe, William. 2004. Can God be Free? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stump, Eleanor and Nathan Kretzmann. 1985. “Absolute Simplicity.” Faith and Philosophy 2(4): 353-382.

The Problem of Evil

Adams, Marilyn. 1999. Horrendous Evils and the Goodness of God. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hick, John. 1966. Evil and the God of Love. New York: Palgrave, 1966.

Rowe, William. 1979. “The Problem of Evil and Some Varieties of Atheism.” American Philosophical Quarterly 16(4): 335-341.

Stump, Eleanor. 2010. Wandering in Darkness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stump, Eleanor. 1983. “Knowledge, Freedom and the Problem of Evil.” International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 14(1): 49-58.

Swinburne, Richard. 1998. Providence and the Problem of Evil. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tooley, Michael. 2002. “The Problem of Evil.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/evil/

Divine Hiddenness

Dumsday, Travis. 2010. “Divine Hiddenness and the Responsibility Argument.” Philosophia Christi 12(2): 357-371.

Howard-Snyder, Daniel and Adam Green. 2016. “Hiddenness of God.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/divine-hiddenness/

Howard-Snyder, Daniel. 1996. “The Argument from Divine Hiddenness.” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 26(3): 433-453.

Moser, Paul. 2002. “Cognitive Idolatry and Divine Hiding.” In Divine Hiddenness: New Essays, eds. Howard-Snyder and Moser, 120-148. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schellenberg, John. 1993. Divine Hiddenness and Human Reason. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Schellenberg’s summary: The Hiddenness Argument and the Contribution of Philosophy (1/5). Youtube.

- For those wishing to learn more, see Aquinas’ Summa Contra Gentiles (1934), Book 1, and Augustine’s The City of God, Part II (2013), Book 11. There are many different editions and translations of ancient and medieval philosophers’ works, and it is common practice in the philosophical community to use a standard referencing system that is the same across all of these rather than using page numbers (which differ across the various editions). Here I shall follow the standard referencing, so that students can find the passages cited regardless of the editions they are using. ↵

- As J. L. Mackie once put it, if God was capable of doing what is logically impossible, "he could certainly exist, and have any desired attributes, in defiance of every sort of contrary consideration. The view that there is an absolutely omnipotent being in this sense stands, therefore, right outside the realm of rational enquiry and discussion" (Mackie 1962, 16). ↵

- See also the Summa Theologiae (1912-36), Ia, 25, 3. ↵

- See Chapter 2 for more about St. Anselm and his ontological argument for the existence of God. ↵

- Note that this problem does not necessarily threaten classical theists, since on their view God is timeless. ↵

- Many philosophers go on to add a third premise, taking it to be a hidden or necessary premise in Mackie’s argument:

- If God is omniscient, he knows about all of the world’s evils and how to eradicate them;

- Classical theists like Aquinas do acknowledge the challenge evil poses, but the argument plays out rather differently if God is immutable and impassible. ↵

- The argument thus assumes that God could not have created a world in which people both possess libertarian free will and never bring about evil—a questionable assumption, to be sure, but one we shall not challenge here. ↵

- Note that this is a contestable premise. See Chapter 2, Section 1 on teleological arguments, for instance. ↵

- See the discussion of Pascal’s Wager in Chapter 3, Section 1. ↵

Discussion on The Value of Philosophy

We humans are very prone to suffer from a psychological predicament we might call “the security blanket paradox.” We know the world is full of hazards, and like passengers after a shipwreck, we tend to latch on to something for a sense of safety. We might cling to a possession, another person, our cherished beliefs, or any combination of these. The pragmatist philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce speaks of doubt and uncertainty as uncomfortable anxiety-producing states. This would help explain why we tend to cling, even desperately, to beliefs we find comforting. This clinging strategy, however, leads us into a predicament that becomes clear once we notice that having a security blanket just gives us one more thing to worry about. In addition to worrying about our own safety, we now are anxious about our security blanket getting lost or damaged. The asset becomes a liability. The clinging strategy for dealing with uncertainty and fear becomes counterproductive.

While not calling it by this name, Russell describes the intellectual consequences of the security blanket paradox vividly:

The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the cooperation or consent of his deliberate reason. . . The life of the instinctive man is shut up within the circle of his private interests. . . In such a life there is something feverish and confined, in comparison with which the philosophic life is calm and free. The private world of instinctive interests is a small one, set in the midst of a great and powerful world which must, sooner or later, lay our private world in ruins.

The primary value of philosophy according to Russell is that it loosens the grip of uncritically held opinion and opens the mind to a liberating range of new possibilities to explore.

The value of philosophy is, in fact, to be sought largely in its very uncertainty. . . Philosophy, though unable to tell us with certainty what is the true answer to the doubts which it raises, is able to suggest many possibilities which enlarge our thoughts and free them from the tyranny of custom. Thus, while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are, it greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never traveled into the region of liberating doubt, and it keeps alive our sense of wonder by showing familiar things in an unfamiliar aspect.

Here we are faced with a stark choice between the feeling of safety we might derive from clinging to opinions we are accustomed to and the liberation that comes with loosening our grip on these in order to explore new ideas. The paradox of the security blanket should make it clear what choice we should consider rational. Russell, of course, compellingly affirms choosing the liberty of free and open inquiry.

Must we remain forever uncertain about philosophical matters? Russell does hold that some philosophical questions appear to be unanswerable (at least by us). But he doesn’t say this about every philosophical issue. In fact, he gives credit to philosophical successes for the birth of various branches of the sciences. Many of the philosophical questions we care most deeply about, however - like whether our lives are significant, whether there is objective value that transcends our subjective interests - sometimes seem to be unsolvable and so remain perennial philosophical concerns. But we shouldn’t be too certain about this either. Russell is hardly the final authority on what in philosophy is or isn’t resolvable. Keep in mind that Russell was writing about a century ago and a lot has happened in philosophy in the mean time (not in small part thanks to Russell’s own definitive contributions). Problems that looked unsolvable to the best experts a hundred years ago often look quite solvable by current experts. The sciences are no different in this regard. The structure of DNA would not have been considered knowable fairly recently. That there was such a structure to discover could not even have been conceivable prior to Mendel and Darwin (and here we are only talking less than two centuries ago).

Further, it is often possible to make real progress in understanding issues even when they can’t be definitively settled. We can often rule out many potential answers to philosophical questions even when we can’t narrow things down to a single correct answer. And we can learn a great deal about the implications of and challenges for the possible answers that remain.

Even where philosophy can’t settle an issue, it’s not quite correct to conclude that there is no right answer. When we can’t settle an issue this usually just tells us something about our own limitations. There may still be a specific right answer; we just can’t tell conclusively what it is. It’s easy to appreciate this point with a non-philosophical issue. Perhaps we can’t know whether or not there is intelligent life on other planets. But, surely either there is or there isn’t intelligent life on other planets. Similarly, we may never establish that humans do or don’t have free will, but it still seems that there must be some fact of the matter. It would be intellectually arrogant of us to think that a question has no right answer just because we aren’t able to figure out what that answer is.

Review and Discussion Questions

The following questions will help you organize your thoughts about the past few chapters. Feel free to take these questions up on the discussion board.

On this lecture note:

- Why should we doubt that science covers all of human inquiry?

- What are some metaphysical issues? Some epistemological and ethical issues?

- What problem does the view that morality is simply a matter of the say-so of some authority lead to?

On Russell’s “The Value of Philosophy”:

-

- What is the aim of philosophy according to Russell?

- How is philosophy connected to the sciences?

- What value is there in the uncertainty that philosophical inquiry often produces?

In Chapter 3, the commentary on Russell:

- Explain the “security blanket” paradox.

- How can understanding of issues be advanced even when definitive knowledge can’t be had?

- What’s the difference between saying we can’t know the answer to some question and saying that there is no truth of the matter?

Finally, consider some of the definitions of philosophy offered by philosophers on: http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2012/04/09/what-is-philosophy/

Why do we cite?

Ever wonder why researchers and scholars are so keen on citing sources? Well, it's not just about following rules; it's a crucial part of the intellectual game. Let's break it down in simpler terms to see why citing is so important.

- Respecting the Thinkers Before Us: When we cite, we're basically saying, "Hey, I got some of my ideas from these smart folks who came before me." It's a way of giving credit to the people who did the groundwork and paved the way for our own thinking.

- Making Sure Information is Trustworthy: Imagine reading something important, like a research paper. You want to know that what you're reading is legit, right? Citing helps with that. When authors mention where they got their info, it's like showing their sources. This makes the whole thing more trustworthy.

- Joining the Conversation: Think of scholarly work as a big conversation. When we cite others, we're jumping into that conversation. We're saying, "I agree with this part," or "I think this idea needs more exploring." It's a way of contributing to the ongoing discussion in our field.

- Avoiding Copying and Cheating: Citing is also a superhero move against plagiarism, which is like copying someone else's homework. When we cite, we're saying, "I'm not stealing this; I'm giving credit where it's due." It's an important way of keeping things fair and square.

- Showing Our Work: Remember how teachers would ask you to show your work in math class? Citing is a bit like that. We're showing how we arrived at our conclusions. It's not just about the final answer; it's about the steps we took to get there. This helps others understand and maybe even replicate our research.

So, in a nutshell, citing is like a respectful nod to those who came before us, a way of making sure information is solid, a ticket to join the scholarly conversation, a guard against cheating, and a method for showing our work. It's a simple but powerful tool that keeps the wheels of knowledge turning smoothly.

APA Style

For this philosophy course, I've opted to follow the guidelines of the American Psychological Association (APA) style. The decision to use APA stems from its clear and structured format, which is particularly beneficial when communicating complex ideas in a formal academic setting. Whenever you cite, you must follow this guidelines.

To learn more about APA style citation, here are the Seneca Library Guidelines for APA Style citation.

And you can find also some exercises in this Pressbook. APPA Style Citation Tutorial.

Reading: The first Reading is Chapter 15 of Bertrand Russell’s Problems of Philosophy, “The Value of Philosophy.”

Chapter XV. The Value of Philosophy.

Having now come to the end of our brief and very incomplete review of the problems of philosophy, it will be well to consider, in conclusion, what is the value of philosophy and why it ought to be studied. It is the more necessary to consider this question, in view of the fact that many men, under the influence of science or of practical affairs, are inclined to doubt whether philosophy is anything better than innocent but useless trifling, hair-splitting distinctions, and controversies on matters concerning which knowledge is impossible.

This view of philosophy appears to result, partly from a wrong conception of the ends of life, partly from a wrong conception of the kind of goods which philosophy strives to achieve. Physical science, through the medium of inventions, is useful to innumerable people who are wholly ignorant of it; thus the study of physical science is to be recommended, not only, or primarily, because of the effect on the student, but rather because of the effect on mankind in general. Thus utility does not belong to philosophy. If the study of philosophy has any value at all for others than students of philosophy, it must be only indirectly, through its effects upon the lives of those who study it. It is in these effects, therefore, if anywhere, that the value of philosophy must be primarily sought.

But further, if we are not to fail in our endeavour to determine the value of philosophy, we must first free our minds from the prejudices of what are wrongly called 'practical' men. The 'practical' man, as this word is often used, is one who recognizes only material needs, who realizes that men must have food for the body, but is oblivious of the necessity of providing food for the mind. If all men were well off, if poverty and disease had been reduced to their lowest possible point, there would still remain much to be done to produce a valuable society; and even in the existing world the goods of the mind are at least as important as the goods of the body. It is exclusively among the goods of the mind that the value of philosophy is to be found; and only those who are not indifferent to these goods can be persuaded that the study of philosophy is not a waste of time.

Philosophy, like all other studies, aims primarily at knowledge. The knowledge it aims at is the kind of knowledge which gives unity and system to the body of the sciences, and the kind which results from a critical examination of the grounds of our convictions, prejudices, and beliefs. But it cannot be maintained that philosophy has had any very great measure of success in its attempts to provide definite answers to its questions. If you ask a mathematician, a mineralogist, a historian, or any other man of learning, what definite body of truths has been ascertained by his science, his answer will last as long as you are willing to listen. But if you put the same question to a philosopher, he will, if he is candid, have to confess that his study has not achieved positive results such as have been achieved by other sciences. It is true that this is partly accounted for by the fact that, as soon as definite knowledge concerning any subject becomes possible, this subject ceases to be called philosophy, and becomes a separate science. The whole study of the heavens, which now belongs to astronomy, was once included in philosophy; Newton's great work was called 'the mathematical principles of natural philosophy'. Similarly, the study of the human mind, which was a part of philosophy, has now been separated from philosophy and has become the science of psychology. Thus, to a great extent, the uncertainty of philosophy is more apparent than real: those questions which are already capable of definite answers are placed in the sciences, while those only to which, at present, no definite answer can be given, remain to form the residue which is called philosophy.

This is, however, only a part of the truth concerning the uncertainty of philosophy. There are many questions—and among them those that are of the profoundest interest to our spiritual life—which, so far as we can see, must remain insoluble to the human intellect unless its powers become of quite a different order from what they are now. Has the universe any unity of plan or purpose, or is it a fortuitous concourse of atoms? Is consciousness a permanent part of the universe, giving hope of indefinite growth in wisdom, or is it a transitory accident on a small planet on which life must ultimately become impossible? Are good and evil of importance to the universe or only to man? Such questions are asked by philosophy, and variously answered by various philosophers. But it would seem that, whether answers be otherwise discoverable or not, the answers suggested by philosophy are none of them demonstrably true. Yet, however slight may be the hope of discovering an answer, it is part of the business of philosophy to continue the consideration of such questions, to make us aware of their importance, to examine all the approaches to them, and to keep alive that speculative interest in the universe which is apt to be killed by confining ourselves to definitely ascertainable knowledge.

Many philosophers, it is true, have held that philosophy could establish the truth of certain answers to such fundamental questions. They have supposed that what is of most importance in religious beliefs could be proved by strict demonstration to be true. In order to judge of such attempts, it is necessary to take a survey of human knowledge, and to form an opinion as to its methods and its limitations. On such a subject it would be unwise to pronounce dogmatically; but if the investigations of our previous chapters have not led us astray, we shall be compelled to renounce the hope of finding philosophical proofs of religious beliefs. We cannot, therefore, include as part of the value of philosophy any definite set of answers to such questions. Hence, once more, the value of philosophy must not depend upon any supposed body of definitely ascertainable knowledge to be acquired by those who study it.

The value of philosophy is, in fact, to be sought largely in its very uncertainty. The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the co-operation or consent of his deliberate reason. To such a man the world tends to become definite, finite, obvious; common objects rouse no questions, and unfamiliar possibilities are contemptuously rejected. As soon as we begin to philosophize, on the contrary, we find, as we saw in our opening chapters, that even the most everyday things lead to problems to which only very incomplete answers can be given. Philosophy, though unable to tell us with certainty what is the true answer to the doubts which it raises, is able to suggest many possibilities which enlarge our thoughts and free them from the tyranny of custom. Thus, while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are, it greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never travelled into the region of liberating doubt, and it keeps alive our sense of wonder by showing familiar things in an unfamiliar aspect.

Apart from its utility in showing unsuspected possibilities, philosophy has a value—perhaps its chief value—through the greatness of the objects which it contemplates, and the freedom from narrow and personal aims resulting from this contemplation. The life of the instinctive man is shut up within the circle of his private interests: family and friends may be included, but the outer world is not regarded except as it may help or hinder what comes within the circle of instinctive wishes. In such a life there is something feverish and confined, in comparison with which the philosophic life is calm and free. The private world of instinctive interests is a small one, set in the midst of a great and powerful world which must, sooner or later, lay our private world in ruins. Unless we can so enlarge our interests as to include the whole outer world, we remain like a garrison in a beleagured fortress, knowing that the enemy prevents escape and that ultimate surrender is inevitable. In such a life there is no peace, but a constant strife between the insistence of desire and the powerlessness of will. In one way or another, if our life is to be great and free, we must escape this prison and this strife.

One way of escape is by philosophic contemplation. Philosophic contemplation does not, in its widest survey, divide the universe into two hostile camps—friends and foes, helpful and hostile, good and bad—it views the whole impartially. Philosophic contemplation, when it is unalloyed, does not aim at proving that the rest of the universe is akin to man. All acquisition of knowledge is an enlargement of the Self, but this enlargement is best attained when it is not directly sought. It is obtained when the desire for knowledge is alone operative, by a study which does not wish in advance that its objects should have this or that character, but adapts the Self to the characters which it finds in its objects. This enlargement of Self is not obtained when, taking the Self as it is, we try to show that the world is so similar to this Self that knowledge of it is possible without any admission of what seems alien. The desire to prove this is a form of self-assertion and, like all self-assertion, it is an obstacle to the growth of Self which it desires, and of which the Self knows that it is capable. Self-assertion, in philosophic speculation as elsewhere, views the world as a means to its own ends; thus it makes the world of less account than Self, and the Self sets bounds to the greatness of its goods. In contemplation, on the contrary, we start from the not-Self, and through its greatness the boundaries of Self are enlarged; through the infinity of the universe the mind which contemplates it achieves some share in infinity.

For this reason greatness of soul is not fostered by those philosophies which assimilate the universe to Man. Knowledge is a form of union of Self and not-Self; like all union, it is impaired by dominion, and therefore by any attempt to force the universe into conformity with what we find in ourselves. There is a widespread philosophical tendency towards the view which tells us that Man is the measure of all things, that truth is man-made, that space and time and the world of universals are properties of the mind, and that, if there be anything not created by the mind, it is unknowable and of no account for us. This view, if our previous discussions were correct, is untrue; but in addition to being untrue, it has the effect of robbing philosophic contemplation of all that gives it value, since it fetters contemplation to Self. What it calls knowledge is not a union with the not-Self, but a set of prejudices, habits, and desires, making an impenetrable veil between us and the world beyond. The man who finds pleasure in such a theory of knowledge is like the man who never leaves the domestic circle for fear his word might not be law.

The true philosophic contemplation, on the contrary, finds its satisfaction in every enlargement of the not-Self, in everything that magnifies the objects contemplated, and thereby the subject contemplating. Everything, in contemplation, that is personal or private, everything that depends upon habit, self-interest, or desire, distorts the object, and hence impairs the union which the intellect seeks. By thus making a barrier between subject and object, such personal and private things become a prison to the intellect. The free intellect will see as God might see, without a here and now, without hopes and fears, without the trammels of customary beliefs and traditional prejudices, calmly, dispassionately, in the sole and exclusive desire of knowledge—knowledge as impersonal, as purely contemplative, as it is possible for man to attain. Hence also the free intellect will value more the abstract and universal knowledge into which the accidents of private history do not enter, than the knowledge brought by the senses, and dependent, as such knowledge must be, upon an exclusive and personal point of view and a body whose sense-organs distort as much as they reveal.

The mind which has become accustomed to the freedom and impartiality of philosophic contemplation will preserve something of the same freedom and impartiality in the world of action and emotion. It will view its purposes and desires as parts of the whole, with the absence of insistence that results from seeing them as infinitesimal fragments in a world of which all the rest is unaffected by any one man's deeds. The impartiality which, in contemplation, is the unalloyed desire for truth, is the very same quality of mind which, in action, is justice, and in emotion is that universal love which can be given to all, and not only to those who are judged useful or admirable. Thus contemplation enlarges not only the objects of our thoughts, but also the objects of our actions and our affections: it makes us citizens of the universe, not only of one walled city at war with all the rest. In this citizenship of the universe consists man's true freedom, and his liberation from the thraldom of narrow hopes and fears.

Thus, to sum up our discussion of the value of philosophy; Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves; because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation; but above all because, through the greatness of the universe which philosophy contemplates, the mind also is rendered great, and becomes capable of that union with the universe which constitutes its highest good.

Reading: The first Reading is Chapter 15 of Bertrand Russell’s Problems of Philosophy, “The Value of Philosophy.”

Chapter XV. The Value of Philosophy.

Having now come to the end of our brief and very incomplete review of the problems of philosophy, it will be well to consider, in conclusion, what is the value of philosophy and why it ought to be studied. It is the more necessary to consider this question, in view of the fact that many men, under the influence of science or of practical affairs, are inclined to doubt whether philosophy is anything better than innocent but useless trifling, hair-splitting distinctions, and controversies on matters concerning which knowledge is impossible.

This view of philosophy appears to result, partly from a wrong conception of the ends of life, partly from a wrong conception of the kind of goods which philosophy strives to achieve. Physical science, through the medium of inventions, is useful to innumerable people who are wholly ignorant of it; thus the study of physical science is to be recommended, not only, or primarily, because of the effect on the student, but rather because of the effect on mankind in general. Thus utility does not belong to philosophy. If the study of philosophy has any value at all for others than students of philosophy, it must be only indirectly, through its effects upon the lives of those who study it. It is in these effects, therefore, if anywhere, that the value of philosophy must be primarily sought.

But further, if we are not to fail in our endeavour to determine the value of philosophy, we must first free our minds from the prejudices of what are wrongly called 'practical' men. The 'practical' man, as this word is often used, is one who recognizes only material needs, who realizes that men must have food for the body, but is oblivious of the necessity of providing food for the mind. If all men were well off, if poverty and disease had been reduced to their lowest possible point, there would still remain much to be done to produce a valuable society; and even in the existing world the goods of the mind are at least as important as the goods of the body. It is exclusively among the goods of the mind that the value of philosophy is to be found; and only those who are not indifferent to these goods can be persuaded that the study of philosophy is not a waste of time.

Philosophy, like all other studies, aims primarily at knowledge. The knowledge it aims at is the kind of knowledge which gives unity and system to the body of the sciences, and the kind which results from a critical examination of the grounds of our convictions, prejudices, and beliefs. But it cannot be maintained that philosophy has had any very great measure of success in its attempts to provide definite answers to its questions. If you ask a mathematician, a mineralogist, a historian, or any other man of learning, what definite body of truths has been ascertained by his science, his answer will last as long as you are willing to listen. But if you put the same question to a philosopher, he will, if he is candid, have to confess that his study has not achieved positive results such as have been achieved by other sciences. It is true that this is partly accounted for by the fact that, as soon as definite knowledge concerning any subject becomes possible, this subject ceases to be called philosophy, and becomes a separate science. The whole study of the heavens, which now belongs to astronomy, was once included in philosophy; Newton's great work was called 'the mathematical principles of natural philosophy'. Similarly, the study of the human mind, which was a part of philosophy, has now been separated from philosophy and has become the science of psychology. Thus, to a great extent, the uncertainty of philosophy is more apparent than real: those questions which are already capable of definite answers are placed in the sciences, while those only to which, at present, no definite answer can be given, remain to form the residue which is called philosophy.

This is, however, only a part of the truth concerning the uncertainty of philosophy. There are many questions—and among them those that are of the profoundest interest to our spiritual life—which, so far as we can see, must remain insoluble to the human intellect unless its powers become of quite a different order from what they are now. Has the universe any unity of plan or purpose, or is it a fortuitous concourse of atoms? Is consciousness a permanent part of the universe, giving hope of indefinite growth in wisdom, or is it a transitory accident on a small planet on which life must ultimately become impossible? Are good and evil of importance to the universe or only to man? Such questions are asked by philosophy, and variously answered by various philosophers. But it would seem that, whether answers be otherwise discoverable or not, the answers suggested by philosophy are none of them demonstrably true. Yet, however slight may be the hope of discovering an answer, it is part of the business of philosophy to continue the consideration of such questions, to make us aware of their importance, to examine all the approaches to them, and to keep alive that speculative interest in the universe which is apt to be killed by confining ourselves to definitely ascertainable knowledge.

Many philosophers, it is true, have held that philosophy could establish the truth of certain answers to such fundamental questions. They have supposed that what is of most importance in religious beliefs could be proved by strict demonstration to be true. In order to judge of such attempts, it is necessary to take a survey of human knowledge, and to form an opinion as to its methods and its limitations. On such a subject it would be unwise to pronounce dogmatically; but if the investigations of our previous chapters have not led us astray, we shall be compelled to renounce the hope of finding philosophical proofs of religious beliefs. We cannot, therefore, include as part of the value of philosophy any definite set of answers to such questions. Hence, once more, the value of philosophy must not depend upon any supposed body of definitely ascertainable knowledge to be acquired by those who study it.

The value of philosophy is, in fact, to be sought largely in its very uncertainty. The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the co-operation or consent of his deliberate reason. To such a man the world tends to become definite, finite, obvious; common objects rouse no questions, and unfamiliar possibilities are contemptuously rejected. As soon as we begin to philosophize, on the contrary, we find, as we saw in our opening chapters, that even the most everyday things lead to problems to which only very incomplete answers can be given. Philosophy, though unable to tell us with certainty what is the true answer to the doubts which it raises, is able to suggest many possibilities which enlarge our thoughts and free them from the tyranny of custom. Thus, while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are, it greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never travelled into the region of liberating doubt, and it keeps alive our sense of wonder by showing familiar things in an unfamiliar aspect.

Apart from its utility in showing unsuspected possibilities, philosophy has a value—perhaps its chief value—through the greatness of the objects which it contemplates, and the freedom from narrow and personal aims resulting from this contemplation. The life of the instinctive man is shut up within the circle of his private interests: family and friends may be included, but the outer world is not regarded except as it may help or hinder what comes within the circle of instinctive wishes. In such a life there is something feverish and confined, in comparison with which the philosophic life is calm and free. The private world of instinctive interests is a small one, set in the midst of a great and powerful world which must, sooner or later, lay our private world in ruins. Unless we can so enlarge our interests as to include the whole outer world, we remain like a garrison in a beleagured fortress, knowing that the enemy prevents escape and that ultimate surrender is inevitable. In such a life there is no peace, but a constant strife between the insistence of desire and the powerlessness of will. In one way or another, if our life is to be great and free, we must escape this prison and this strife.

One way of escape is by philosophic contemplation. Philosophic contemplation does not, in its widest survey, divide the universe into two hostile camps—friends and foes, helpful and hostile, good and bad—it views the whole impartially. Philosophic contemplation, when it is unalloyed, does not aim at proving that the rest of the universe is akin to man. All acquisition of knowledge is an enlargement of the Self, but this enlargement is best attained when it is not directly sought. It is obtained when the desire for knowledge is alone operative, by a study which does not wish in advance that its objects should have this or that character, but adapts the Self to the characters which it finds in its objects. This enlargement of Self is not obtained when, taking the Self as it is, we try to show that the world is so similar to this Self that knowledge of it is possible without any admission of what seems alien. The desire to prove this is a form of self-assertion and, like all self-assertion, it is an obstacle to the growth of Self which it desires, and of which the Self knows that it is capable. Self-assertion, in philosophic speculation as elsewhere, views the world as a means to its own ends; thus it makes the world of less account than Self, and the Self sets bounds to the greatness of its goods. In contemplation, on the contrary, we start from the not-Self, and through its greatness the boundaries of Self are enlarged; through the infinity of the universe the mind which contemplates it achieves some share in infinity.

For this reason greatness of soul is not fostered by those philosophies which assimilate the universe to Man. Knowledge is a form of union of Self and not-Self; like all union, it is impaired by dominion, and therefore by any attempt to force the universe into conformity with what we find in ourselves. There is a widespread philosophical tendency towards the view which tells us that Man is the measure of all things, that truth is man-made, that space and time and the world of universals are properties of the mind, and that, if there be anything not created by the mind, it is unknowable and of no account for us. This view, if our previous discussions were correct, is untrue; but in addition to being untrue, it has the effect of robbing philosophic contemplation of all that gives it value, since it fetters contemplation to Self. What it calls knowledge is not a union with the not-Self, but a set of prejudices, habits, and desires, making an impenetrable veil between us and the world beyond. The man who finds pleasure in such a theory of knowledge is like the man who never leaves the domestic circle for fear his word might not be law.

The true philosophic contemplation, on the contrary, finds its satisfaction in every enlargement of the not-Self, in everything that magnifies the objects contemplated, and thereby the subject contemplating. Everything, in contemplation, that is personal or private, everything that depends upon habit, self-interest, or desire, distorts the object, and hence impairs the union which the intellect seeks. By thus making a barrier between subject and object, such personal and private things become a prison to the intellect. The free intellect will see as God might see, without a here and now, without hopes and fears, without the trammels of customary beliefs and traditional prejudices, calmly, dispassionately, in the sole and exclusive desire of knowledge—knowledge as impersonal, as purely contemplative, as it is possible for man to attain. Hence also the free intellect will value more the abstract and universal knowledge into which the accidents of private history do not enter, than the knowledge brought by the senses, and dependent, as such knowledge must be, upon an exclusive and personal point of view and a body whose sense-organs distort as much as they reveal.

The mind which has become accustomed to the freedom and impartiality of philosophic contemplation will preserve something of the same freedom and impartiality in the world of action and emotion. It will view its purposes and desires as parts of the whole, with the absence of insistence that results from seeing them as infinitesimal fragments in a world of which all the rest is unaffected by any one man's deeds. The impartiality which, in contemplation, is the unalloyed desire for truth, is the very same quality of mind which, in action, is justice, and in emotion is that universal love which can be given to all, and not only to those who are judged useful or admirable. Thus contemplation enlarges not only the objects of our thoughts, but also the objects of our actions and our affections: it makes us citizens of the universe, not only of one walled city at war with all the rest. In this citizenship of the universe consists man's true freedom, and his liberation from the thraldom of narrow hopes and fears.

Thus, to sum up our discussion of the value of philosophy; Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves; because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation; but above all because, through the greatness of the universe which philosophy contemplates, the mind also is rendered great, and becomes capable of that union with the universe which constitutes its highest good.