15 Personal identity

Matthew Van Cleave

Introduction: the persistence question

Imagine a wooden ship called “TS” that was built 100 years ago and that has been in continual use up until today. As time has passed, parts of TS have decayed and have needed to be replaced. Eventually, none of TS’s parts are original; all of them have been replaced. Is TS the same boat as it was 100 years ago?[1] On the one hand, it seems that it cannot be since the physical object has undergone a radical change—it is literally a totally different physical object. One the other hand, we are inclined to still call it “TS” since it has been in continual use since it was first built and it has always been called “TS.” These two answers suggest two very different criteria about the identity conditions of objects. The first answer suggests that an object is the same object only if there is some intrinsic property of the object that stays the same through time (and that if there are no such properties then it follows that it is no longer the same ship as it was at the start). The second answer suggests that an object is the same object as long as it has some extrinsic property that remains such same. Being called the by the same name (or perceived by people to be the same object) over time is a good example of an extrinsic property since it is not something that the object itself contains but, rather, something that is “put onto” the objection from outside. On this criterion, TS is the same ship since people have always called it “TS.”

The question about the identity of the boat represents a very general metaphysical question about the identity of physical objects: what are the criteria by which objects remain numerically identical? Numerical identity is a term that philosophers use to describe an object being the very same object. It is contrasted with qualitative identity which simply means that an object has all the same properties or qualities. An object is only numerically identical to itself but can be qualitatively identical to other objects. For example, imagine two identical red Corvettes. The two red Corvettes are qualitatively identical (since if you closed your eyes could not tell whether one has been substituted for the other), but they are not numerically identical (because they are two different cars). The persistence question of identity is the question about the conditions under which an object remains numerically identical. For example, if the ship were disassembled and the wood used to build a house, it seems clear that it would no longer be the same object (even if its physical material were the same) since it is no longer a boat but a house. Likewise, if the red Corvette were melted down into metal and then fashioned into a boat, it would no longer be the same object.

Although we can ask the persistence question about objects in general, one kind of thing whose identity conditions philosophers have been very interested in is persons. The persistence question of personal identity is the question about the conditions under which a particular human being remains numerically the same.[2] The philosophical problem is that although it seems that that a person remains numerically identical throughout their life, it is very difficult to give a satisfying answer to what accounts for this numerical identity. More specifically, the problem is that although we are inclined to think that there is some intrinsic property that makes a person numerically the same throughout their life, it is very difficult to come up with what this intrinsic property is. Perhaps there is no intrinsic property; perhaps the only thing that makes me me is that others have always called me “Matt Van Cleave.” However, that answer also seems to lack the depth that we think our personal identity has. After all, it seems that there is a clear sense in which I would still be me even if all of a sudden people started calling me by a different name. Suppose I was kidnapped and taken to a different place where no one knew me but where I looked exactly like someone called Todd Quiring. The fact that everyone now calls me “Todd Quiring” doesn’t seem to change who I am in any deep way.

In this chapter we will consider a few different answers to the persistence question. John Locke’s psychological continuity account and Bernard Williams’s bodily continuity account both attempt to find an intrinsic property that grounds our personal identity. In contrast, Daniel Dennett’s short story “Where am I?” raises the question of whether there is any intrinsic property that grounds personal identity. In philosophy, this idea is famously linked to David Hume, but it also connects with the Buddhist concept of anattā (“no self”). Whereas the persistence question is a metaphysical question, in the last part of the chapter we will consider what I call the psychological question of personal identity: Where does my sense that that I am the same person throughout my life come from? Notice that even if it were to turn out that metaphysically there is no self that persists throughout our whole lives, it still makes sense to ask this psychological question about our sense of our identity. That is, even if there is no deep sense in which I am the same person I was 20 years ago, there can still be an account of what gives me the sense that I am (if indeed I have that sense).[3]

1. Personal identity as an unchanging, intrinsic property

Before considering Locke’s view of personal identity, let’s consider one idea about what kind of thing would answer the persistence question. It is commonly thought our personal identity should consist in some one thing that is unchanging and intrinsic. For example, within certain religious traditions, the idea of an immaterial soul is often seen as the thing that makes us the same person. Although our bodies, our beliefs, and our values may change radically throughout our lifetimes, our soul is thought to stay the same. However, if it is possible for our souls to leave our bodies and inhabit other bodies (such as in reincarnation) then it seems problematic for souls to ground my personal identity. If one soul can inhabit many different persons, then it cannot be the soul that distinguishes one person from another. In addition, positing a soul raises certain kinds of epistemological questions: How do we know that souls exist? Even if souls exist, how do we know they don’t themselves undergo change? How do I know that my soul is the same from one moment to the next? For these reasons and others, philosophers have tended to look elsewhere for an answer the persistence question of personal identity.

Is there some other thing about me that always stays the same? What about my body? Like the example of the ship, my body naturally regenerates all of its physical matter certain number of years (how long depends on which organs/cells we are talking about). Although neurons in our cerebral cortex do not regenerate, the connections between the neurons in our brain are continually changing (this is what happens when learning takes place). In any case, it seems implausible to maintain that some is some particular neuron or set of neurons in the cerebral cortex that account for why I am the same. What about DNA? The DNA within our bodily cells stays largely the same (except when uncorrected errors in replication occur, which is rare). But consider identical twins (which have the same DNA). Clearly identical twins are two different persons. But if DNA were the basis of personal identity, there would be only one person. How about fingerprints—don’t those stay the same throughout my lifetime? Yes, they do—unless I were to lose my hands. But in that case, am I really now a different person? It seems not. The other problem with DNA and fingerprints is that they don’t seem to have much to do with who we are as persons. Many philosophers since Locke have viewed the concept of a person as a forensic concept, meaning a concept that is essentially tied to our notions of moral and legal responsibility. Persons are individuals have have moral and legal rights and can be held responsible for their actions. The problem with DNA and fingerprints is that neither one has much to do with our personhood and agency and for this reason wouldn’t be able to explain much about personal identity. Thus it seems that there is no one physical thing that persists throughout our lifetime that could ground our personal identity. For this reason, philosophical accounts of personal identity have eschewed the idea that there is some one thing that stays same throughout my life. Instead, philosophers have tended to claim that what grounds identity is a kind of continuity between aspects of ourselves at different times.

2. Personal identity as psychological continuity

John Locke (1632-1704) claimed that I remain the same person through time because I am conscious of being the same person through time and that “as far as this consciousness can be extended backwards to any past action or thought, so far reaches the identity of that person.”[4] Locke’s criterion is commonly interpreted as a memory criterion of personal identity: personal identity consists in one’s ability to remember things about their own past from a first-person perspective. For example, since I can remember things about being 20 years old (or even 10 years old) it follows that I am now numerically identical to the person as I was then. The fact that these memories are from the first-person perspective is crucial. It isn’t just that I can remember certain events taking place (since perhaps some of my friends remember those same events). Rather, it is that I remember those events from my first-person perspective. For Locke, what makes a person the same person must be essentially tied to what persons are and for Locke “person” is a forensic concept, meaning a concept that is essentially tied to the concept of agency and thus to our notions of moral and legal responsibility. Persons are individuals who have moral and legal rights and who can be held responsible for their actions. (For this reason, Locke would reject DNA and fingerprints as grounding personal identity since neither one has much to do with the capacities that underlie our lives as agents.)

The memory criterion has a broad appeal since it seems plausible that much of our sense of ourselves is due to our memories of our past. It does seem that without the ability to remember anything about my past (as in cases of severe amnesia or dissociative fugue states) I would not be the same person. Furthermore, the memory criterion of personal identity carries with it a criterion for moral responsibility: we cannot be held responsible for things of which we have no memory. The memory criterion is also appealing because it accounts for the commonly held idea that our minds are central to who we are as persons (since memory is a psychological attribute). Finally, since psychological properties are intrinsic properties of persons, Locke’s memory criterion accounts for the commonly held belief that our personal identities are real and deep. So far, so good. However, the memory criterion is not without its problems.

Suppose that Bob commits a heinous murder when he is 25 years old and is never caught for it. 50 years later he is finally apprehended but now Bob has late stage Alzheimer’s disease and cannot remember anything about his earlier life. What would Locke’s memory criterion say about whether Bob should be punished for the earlier murder? The memory criterion implies that Bob is literally not the same person now as he was then. If we assume that it is fair only to punish the person who committed the crime, it would not be fair to punish Bob today since he is a different person (according to the memory criterion). Think of it this way: it is no more fair to punish Bob for the murder than it is to punish his friend Bill, who had nothing to do with the murder. On Locke’s memory criterion, Bob at 75 years old is no more the same person than Bob at 25 years old than his friend Bill is. Neither one has the right kind of memory connection to Bob at 25 years old. In fact, since no existing person has the right kind of memory connection to 25 year old Bob, it follows that there is no existing person that committed the crime (and thus no one can be punished). Locke anticipated this problem and accepts that if Bob truly cannot remember his earlier life, then it is not fair to punish him (since he is not the same person who committed the murder). However, Locke also thinks that we should still punish people who have committed crimes even if they claim they can’t remember it since if we didn’t, then anyone found guilty of a crime could claim they didn’t remember the crime as a way of exculpating themselves. So Locke thinks that we have to hold people accountable. If we were omniscient like god, then we would know when someone really couldn’t remember (and thus wasn’t the same person) and when they were just lying to escape punishment. But since we aren’t, we are stuck with an inferior kind of justice that may sometimes punish those who don’t deserve it.

Another problem that arises for Locke’s memory criterion is what happens when we are in a state in which we cannot remember anything from our earlier lives— for example, when I am unconscious, such as I am when I sleep. Someone who is asleep does not have the ability to remember earlier events in one’s life and thus it seems to follow that when a person is asleep they are not the same person as when they are awake. Indeed, if personhood requires the ability to remember at all, then it seems that the unconscious person is not really a person at all. But this seems all wrong. It does not seem that when I am sleeping I cease to be numerically identical to the person I am when I am awake. One way of trying to solve this problem would be to broaden the memory criterion. For example, you could say that it is still possible for the sleeping person to remember earlier events in their life, whereas it isn’t possible for the severe Alzheimer’s patient to remember such events. If the sleeping person were simply woken up, they would be able to remember their earlier life. But there is no simple thing that could be done to restore the Alzheimer’s patient’s memory in this way.[5]

One of the most famous objections to the memory criterion turns on the idea that numerical identity is a transitive relationship. When we say that x is numerically identical to y, we mean that x and y are one and the same object. That is, if x is identical to y and y is identical to z, must be true that x is identical to z. Once we understand this, we can see that there is a problem with the memory criterion. Suppose that Roses at age 50 can remember things about Roses at age 25 and that Roses at age 75 can remember things about Roses at age 50. Does it follow that Roses at age 75 can remember things about Roses at age 25? It should be clear that it doesn’t follow and this shows that memory is not in general a transitive relationship. Now here is the problem. According to the memory criterion two persons are identical if the later one can first- personally remember things that happened to the earlier one. So Roses at 25 and Roses at 50 are identical. Likewise, Roses at 50 and Roses at 75 are identical. But as we saw above, numerical identity is transitive, so it must follow that Roses at 25 and Roses at 75 are numerically identical. But as we have just seen, it doesn’t follow because memory is not transitive in the way numerical identity is. Therefore, memory cannot be the same as numerical identity.

Therefore, the memory criterion cannot be correct.[6] How might Locke respond to this objection? On the one hand, Locke seems happy to admit that you have not always been the same person throughout your life (since you aren’t when you’re sleeping) and that you may become a wholly different person (as in the case of Bob, above). So Locke might be content to just allow that the lifetime of Roses consists of more than one different person. On the other hand, if we are looking for a sense of personal identity that lasts throughout a person’s lifetime, then in some cases (for example, cases where there are memory failures) we will have to say that there are multiple different persons that have existed in the course of one lifetime.

Philosophers continue to debate Locke’s memory criterion, but many philosophers influenced by Locke have tended to move to a broader psychological continuity account of personal identity. On these accounts, what makes us a person numerically identical through time is that there are causal connections between our psychological states. For example, at age 10 I had a certain set of beliefs, desires, and memories (all different kinds of psychological states). At age 11 I probably had a similar set of psychological states, although of course new ones had been added and some changed. But what makes me at 11 the same as me at age 10 is that the psychological states I had at age 10 were causally involved in bringing about the psychological states I had at age 11. It is these causal relationships between my psychological states that tie me back to these older versions of myself and thus account for my persistence through time.

Psychological continuity accounts of personal identity retain the Lockean identification of our persisting identities with our psychological states, but they reject the Lockean idea that these must be consciously accessible mental states. So, in a sense, I don’t have to be able to maintain the persistence of my identity through time (for example, by consciously connecting myself now to myself ten years ago). Rather, my identity is maintained by the causal relationships between my psychological states. The result of making this relationship causal is that my personal identity can persist despite my lack of memory. This solved several of the problems that were raised for the memory criterion. For example, if I am asleep or awake my persisting beliefs, desires, and values do not change. When I am asleep, I still believe that George Washington was the first U.S. president, that water contains hydrogen atoms, that I had a piñata at my tenth birthday party, and liberal democracies are in theory the least bad form of government. What makes me the same person while I am asleep is that my psychological states while asleep are caused by my previous psychological states while I was awake. It doesn’t matter, as it did for Locke’s memory criterion, that I cannot consciously access these psychological states while asleep. Likewise, making the continuity between our psychological states causal rather than conscious solves the transitivity problem explained above. It doesn’t matter that Roses at 75 cannot remember anything about Roses at 25. Rather, what matters is that Roses’s psychological states at 75 can be traced back in causal line to Roses’s psychological states at 25. Of course, her psychological states may have changed radically in that time, but that doesn’t matter. In this way, psychological continuity accounts allow for the possibility of persistence despite radical change. And in some sense this is exactly what our common sense intuitions suggest about the persistence of our identities through time: although we can change radically, nonetheless, there is still a sense in which we remain the same.

But how radical can the change be and the individual still persist? The most difficult problem for psychological continuity accounts is called the fission problem. Suppose we perform a hemispherectomy (splitting the brain in two at the corpus callosum and then removing one half) on “Lefty” and transplant the right half of his brain into another person (call him “Righty”). The psychological continuity view would seem to imply that Lefty and Righty are the same person since both are psychologically continuous with Lefty. But it seems there are now two people whereas the psychological continuity view implies that there is only one person. This is the fission problem. One thing the psychological continuity theorist could say in response to the fission problem is that since there is a radical, exogenous causal disruption of Lefty’s psychological states (“half” of them are removed and put into another person), that Lefty ceases to exist since the causal continuity of his psychological states is disrupted. In this case, one person ceases to exist and two different ones, Lefty2 and Righty come into existence. This seems a sensible way of responding to bizarre thought experiments like the one above. After all, it isn’t intuitively obvious that Lefty continues to exist after such a radical procedure. On the other hand, if we think that Lefty remains numerically identical even after the hemispherectomy, then the psychological continuity view would imply that Righty is also Lefty and that seems to be an absurdity.

3. Personal identity as bodily continuity

The bodily continuity account of personal identity, as I am using that term here, contrasts with psychological continuity accounts in that it claims that what accounts for our persistence through time is our bodily continuity, not our psychological continuity. A famous argument for the bodily continuity account comes from the philosopher Bernard Williams.[7] Williams has us imagine the following sci-fi thought experiment. Suppose that you are told that you will be painfully tortured tomorrow but that before you are a certain procedure will be performed on you: all of your psychological states (memories, beliefs, desires, and so on) will be wiped clean. That is, you will become complete amnesiac, remembering nothing of who you are or were. You will become essentially a blank slate. Psychological continuity accounts would seem to imply that in this state you have ceased to exist. Thus, the person that will be tortured tomorrow will not be you. However, it seems that this would be cold comfort to the person facing this prospect. That is, it seems we would still now fear the torture that will occur tomorrow, even if none of our psychological states remain when we are undergoing the torture. To Williams, the fact that we still fear the torture implies that we do not identity ourselves with our psychological states, but rather with our bodies. How else could you explain why we would fear the torture? It seems that the psychological continuity account of our identity would say that we shouldn’t fear the torture since the person being tortured tomorrow will not be us. Be since we do fear the torture, this implies that we do identify ourselves with that individual who will be tortured tomorrow.

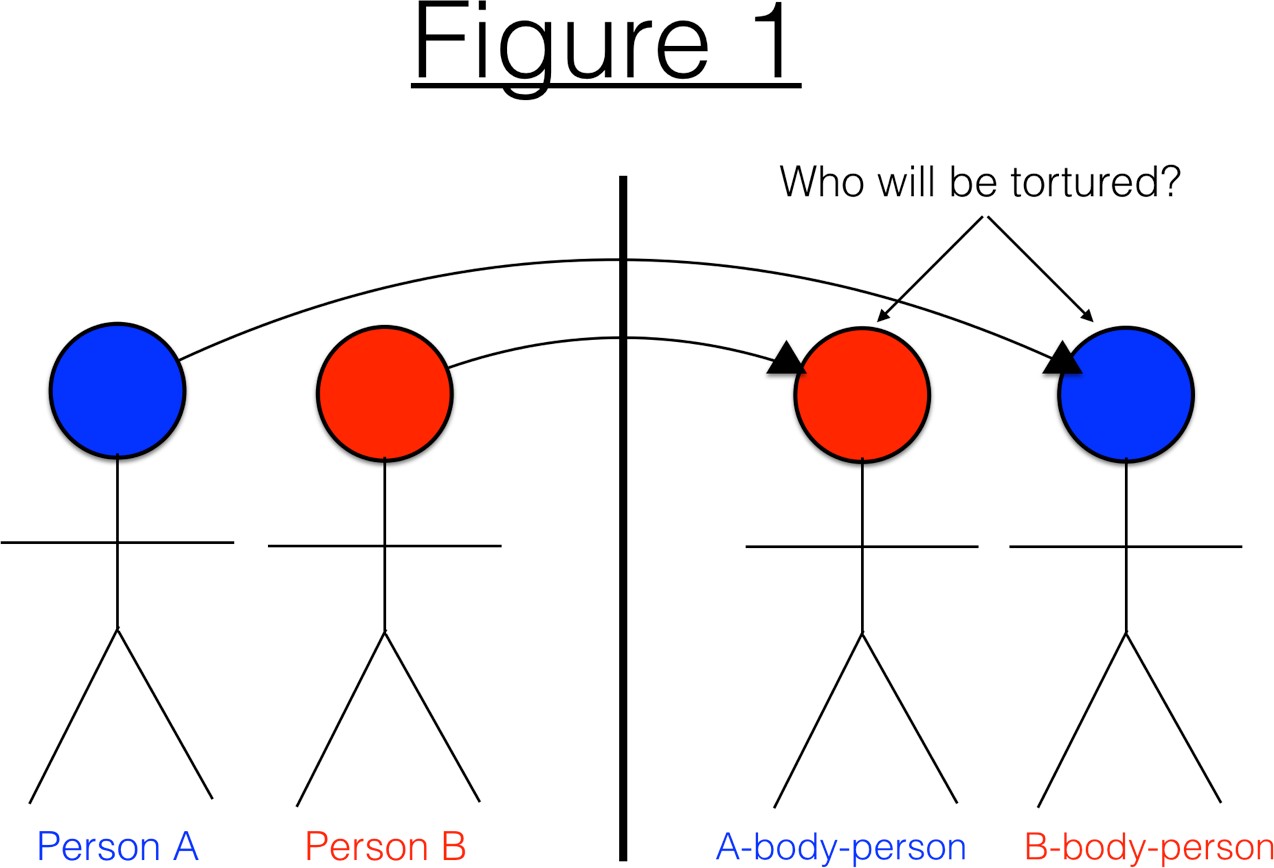

Williams argues that this is so even if we imagine switching all of our psychological states with another person—that is, all of their psychological states are transferred to our brain/body and all of ours, to their brain/body. Again, the psychological continuity view would seem to imply that the personal identities of these two bodies have switched: the A-body person takes on B’s identity and the B-body person takes on A’s identity. Figure 1 below is a representation of this situation.

Suppose that you are A in the above scenario and suppose that you are reasoning purely in terms of self-interest (that is, you want to avoid being tortured). Who would you say should be tortured tomorrow: the A-body person or the B-body person? Williams think that we would say the B-body person should be tortured, even if the B-body person inherits all of our psychological states! Since psychological continuity accounts (including the Lockean memory criterion) imply that person A now exists in the B-body person, then such accounts imply that we should say that the A-body person should be tortured. The fact that we would say that the B-body person should be tortured is supposed to clearly refute psychological continuity theories, according to Williams (or at least to raise a serious problem for them). Again, what we seem to be doing in a case like this is identifying ourselves not with the continuity of our psychological states, but rather with the continuity of our bodies.

If you aren’t already convinced that if you were A, you would identity with the A- body person after the transfer of psychological states (and with the prospect of the impending doom of torture applied to the A-body person), Williams walks through a series of thought experiments, starting with the above amnesia scenario. Since he thinks we would clearly still fear torture (now) even if we were to be given total amnesia before the torture took place, he uses this to show that there is no difference between the amnesia scenario and the psychological transfer scenario, described above. Willliams walks us through the following permutations of the amnesiac scenario in order to arrive at the transfer scenario, claiming that none of the changes should make a difference to our answer of who should be tortured:

- Total amnesia

- Total amnesia + totally new memories created

- Total amnesia + totally new memories that come from some other existing person, call them “B-person”

- Total amnesia + totally new memories that come from some other existing person + your memories (that have been wiped clean) are given to that other B-person)

This last scenario is just the same transfer scenario described above. Williams claims that if you said that the B-body person should be tortured in the amnesia scenario then you should logically say the same thing in the transfer scenario, since there are no relevant changes in any of the scenarios through which the amnesia scenario is transformed into the transfer scenario.

One puzzling thing about Williams’s article is that he seems to equate transfer scenarios like the one above (where all psychological states are transferred) to brain transfer scenarios and it is not at all obvious that this is so.[8] Although it seems to me correct that we should identify with our bodies rather than our mental states in the psychological state transfer scenario, we should not identify our bodies in a brain transfer scenario. If you are A in the scenario and your brain will be transferred to B’s body, then it seems to me that you should choose the A-body person to be tortured. In this case, you won’t feel it because the seat of consciousness that underlies our experiences (whether of pleasure or pain) has now shifted, with the transfer of my brain, to B’s body. Therefore, you should choose the A-body person to be tortured. If this is right, then it seems like Williams’s scenario doesn’t really show that we identify with our bodies, as such. Rather, it shows that we identify with our brains—specifically with our first- person conscious experience that we think goes where our brain goes. (As we will see presently, Dennett’s sci-fi story will challenge this intuition.) The remains behind when we transfer all of our psychological states is the seat of conscious experience—that which is capable of experiencing pleasure and pain. The reason we would choose the B-body person to be tortured is that although they have all of our psychological states, they do not have our seat of consciousness—our first-person conscious experience. That remains behind with our brain, even if all of our psychological states are extracted from it and replace with B’s psychological states. In contrast, in the brain transfer scenario, not only all of our psychological states are being transferred, so also is our seat of conscious experience itself. But since the “seat of conscious experience” is as much a psychological property as it is a physical property (the brain), Williams’s argument doesn’t really show that we identify our persistence with some aspect of our bodies (brains) rather than some aspect of our minds (consciousness).[9]

Within contemporary philosophical debates about the persistence question, the view that aligns most closely with bodily accounts of personal identity is a view called animalism.[10] Contrary to Lockean accounts of the persistence of our personal identity in terms of our psychological properties, animalists claim that what accounts for our persistence through time is our animal properties. Yes, we are thinking animals, but we are first and foremost animals. According to animalists, our “animal properties” are the ones that account for our persistence through time as the same animal. For example, this could the biological properties that maintain the life of the organism over time—they are what keep the organism from dying and becoming, through decomposition, something else. This means that what accounts for the persistence of individual human beings through time is the same kind of thing that accounts for the persistent of individual dogs or cats or trees through time. A crucial argument that animalists make against Lockean accounts is that only animalism can make sense of the idea that I persist through time from birth to death. As we have seen, accounts which ground our personal identity in our psychological properties have to admit that my personal identity stops when there is a large enough discontinuity in my psychological states. Animalists admit that although I may cease to be a person under certain conditions (for example, if I become a complete amnesiac), I remain an animal and thus I continue to persist through time. Insofar as we think that the essence of who we are is extremely robust and persists through the kinds of radical changes that we can undergo throughout our lifetimes, animalism is an attractive alternative to Lockean answers to the persistence question.

Another argument that animalists have made is called the animal ancestors argument. Suppose, contrary to what animalism claims, we are not essentially animals. If we are not animals, then our parents are not animals either, nor are our grandparents, and so on. But this entails something that is false according to evolutionary theory: that nothing in our ancestry is an animal. But since we know this to be false, it follow that our original assumption must be false. That is, it follows that we must be, in essence, animals. This argument uses a famous form of argument called a reductio ad absurdum (this is Latin for “reduce to absurdity). The argument proceeds by assuming the falsity of a claim P that we is true and then show how if we assume the falsity of that claim P, it leads to an absurdity (strictly, a contradiction). But since absurdities like contradictions cannot be true, if follows that our original assumption (that P is false) must itself be false, which means that P is true.

One interesting objection to animalism is the case of dicephalic twins. The problem is that it looks there are two individuals in the case of dicephalic twins. However, it seems pretty clear that there is only one animal. Dicephalic twins thus constitute a counterexample to animalism’s claim that our identity consists in our animal properties.[11]

4. Dennett’s “Where Am I?”

Daniel Dennett’s, “Where Am I,” is a mind-bending sci-fi short story to read in order to problematize different accounts of personal identity.[12] Arguably, problematizing the concept of personal identity, as well as different accounts of it, is exactly what Dennett was trying to do in writing the story.[13] Regardless of Dennett’s goal, what I will try to do in this section is use the story to show that there is no one way of accounting for our personal identity that can withstand the radical ways in which individual human beings might persist through time. If Dennett is correct, then it is possible that I (my identity) could be spread over many different places at one time (omnipresence!) or even that there could be two individuals that share my numerically identity! I highly recommend that you simply read the story for yourself before reading my own synopsis of it.

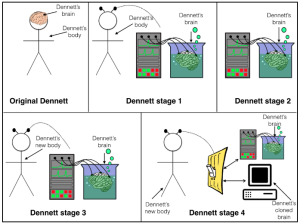

“Where Am I?” begins with Dennett signing up for an expedition in which he must disarm a highly radioactive object underground. Because it is feared that the radioactivity will destroy his brain, an operation is performed in which his brain is removed and placed into a vat of liquid, keeping it vital. In addition, electrodes are implanted both in the neurons in his severed brain and in the brainstem in his body so that the brain can still communicate with the body electronically, at a distance. If you doubt this could be done, just consider that the brain’s neurons are sending many, many simple messages that could be, in theory, relayed through other mediums, like radio waves. As Dennett puts it, the doctors describe the operation procedure as essentially stretching his neurons so that they can communicate with his body from a long distance (wirelessly, by electronic signals like radio waves).

Whilst on the underground expedition, something goes wrong and Dennett’s body is crushed in an accident. Before the accident it seems to Dennett, from his first-person perspective, that he is underground. However, once his body is destroyed, his point of view reverts immediately back to lab, where his brain is in a vat of liquid—miles and miles away from where he just was underground before the accident. At this point, Dennett has no body, just a brain. This would be a frightening position to be in, if you think about it. There is no sensory input, no way of communicating with the outside world.[14] While in this state of extreme sensory deprivation, scientists figure out how to stream Dennett’s favorite classical music (Brahms) straight into his auditory nerve of his brain (thus bypassing the normal way of hearing via the mechanics of our ears).

Eventually, the scientists find a new body for Dennett and connect his original brain to the new body in the aforementioned way (via electrodes in the new body’s brainstem). The newly reimbodied Dennett emerges, now able to communicate with the rest of the world again. Immediately Dennett’s point of view switches from inside the vat (where his brain is) to outside the vat, where his new body is. He walks back into the lab to the applause of all the scientists working on the project and stares at his brain inside the vat of liquid. Earlier, scientists had shown him a switch which turned on/off the transmitter that sent the brain signals electronically to/from the body. Earlier, when he had turned that switch off, his body had collapsed to the floor (since it was no longer connected to the brain). Just for kicks, Dennett now tries this again and miraculously nothing happens. His conscious experience is exactly the same; his point of view is exactly the same; nothing seems to change at all.

Puzzled by this, he asks the scientists who explain that they had actually “cloned” his brain on a computer so that there was an exact replica of his brain that was running the exact same input/output signals to his body. What the new switch did was simply change which thing was connected to his body: the original brain or the clone of his brain on the computer. The putative reason that scientists had done this was just in case Dennett’s brain was destroyed, Dennett could still live on via his “brain” that the computer had cloned. As Dennett flips the switch back and forth, he can tell no difference at all in terms of his point of view and the nature of his conscious experience. It is as if nothing had happened at all.

The last part of the story concerns another upsetting circumstance (both emotionally for the character “Dennett” in the story and philosophically for Dennett, the author of the story). Dennett’s original brain and the computer brain come out of sync with each other—the inputs and outputs no longer match—so that when the switch is thrown to switch what is controlling Dennett’s body, a whole new persona emerges (in this case, from weeks of inability to control the body). In essence, there are now two people controlling Dennett’s (new) body, but only one can control the body at a time. They both receive sensory inputs to the body, but only one can send motor signals to move the body. If you were the person who couldn’t send motor signals to reach the body, you can imagine how distressing this would be.

Below is a diagram which shows each different stage of the story.

Notice what the story seems to entail. Those who say that bodily continuity accounts for our persistence would seem to be incorrect, since Dennett seems to himself in the story to persist even though his original body has been destroyed and replaced by someone else’s body. On the other hand, those who would see our persisting identities as tied to our brains also seem to be mistaken, since we can imagine a further stage of the story (before the computer and brain came out of sync) in which Dennett’s original brain (sitting in the vat of liquid in the lab) was destroyed in a different accident and yet Dennett’s point of view remained the same. So one’s identity is not bodily continuity nor is it, more specifically, the continuity of the brain. This seems to leave open the psychological continuity accounts of personal identity. However, consider one of the paradoxical implications that this story raises for psychological continuity accounts. In the last stage of the story, before the computer and Dennett’s brain have gotten out of sync, it appears that there are two, numerically identical Dennetts, since the information (memories, beliefs, desires) on the clone of Dennett’s brain on the computer is identical to Dennett’s brain. (This is just an instance of the fission problem, explained above.)But there cannot be two, numerically identical objects. Therefore, psychological continuity accounts cannot be correct.

One might take the upshot of Dennett’s story to be that there are no good answers to the persistence questions. That is, perhaps I do not really persist through time at all. The idea that I—my “self”—does not persist through time is an old idea that also arises in older philosophical traditions, both in the East and West. The Buddhist concept of anattā (“no self”) suggests the impermanence and everchanging nature of our personal identities.[15] In the West, David Hume famously claimed that:

For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe anything but the perception. When my perceptions are removed for any time, as by sound sleep; so long am I insensible of myself, and may truly be said not to exist. And were all my perceptions removed by death, and could I neither think, nor feel, nor see, nor love, nor hate after the dissolution of my body, I should be entirely annihilated, nor do I conceive what is farther requisite to make me a perfect non-entity. If anyone, upon serious and unprejudiced reflection thinks he has a different notion of himself, I must confess I can reason no longer with him. All I can allow him is, that he may be in the right as well as I, and that we are essentially different in this particular. He may, perhaps, perceive something simple and continued, which he calls himself; though I am certain there is no such principle in me. But setting aside some metaphysicians of this kind, I may venture to affirm of the rest of mankind, that they are nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement.[16]

Perhaps Hume and the Buddhists are correct. After all, we have seen that there are difficult problems that arise for the different answers to the persistence question. But even if there is no persisting self, it is nevertheless true that many people have the sense that there is. A separate question concerns how to best explain where our sense that we persist through time comes from. In the last couple of decades, an interdisciplinary view has become very influential: the narrative conception of the self. In the next section we will consider this view.

5. The narrative conception of the self

Why does it feel to me that there is a persisting self? According to the narrative conception of the self, what unifies our lives—that is, what makes it seem that me at 10 years old is the same as me at 43 years old—is the stories we tell about ourselves that connect the different parts of our lives. For example, I, Matthew Van Cleave, am the person who grew up in a small town, became a runner in high school and college, played in a rock band in college, and then after college decided to become a philosopher and so went back to graduate school to earn a PhD in Philosophy. Furthermore, narratives have a certain kind of structure to them: there is beginning, middle and end. Importantly, the end of the narrative is what enables us to make sense of and assess who we are at any point within the narrative. The end of the narrative is what provides guidance throughout the narrative: what counts a good or bad decision is relative to the end goal/purpose of the life whose narrative is being narrated. For example, if the end of my story concerns being a successful philosophy professor and having a profound impact on my students and colleagues, then this end is what my life is working towards and the parts of my life constitute my self insofar as they are a part of this narrative structure. According to the narrative view of the self, who we are is just the story that we tell about ourselves. Notice that the story we tell about the events is different than the events themselves. The narratives we construct of our lives are post-hoc (Latin for “after this”) in the sense that we construct them after the events have already happened. But as mentioned above, a narrative can also exert a normative influence over what we choose to do in the future. For example, I might choose not to take a much higher paying job in the business world because it doesn’t cohere with my narrative of myself as an influential and respected philosopher. Or I might decide to return the credit card I found on the sidewalk instead of trying to use it because using it would be inconsistent with my narrative of myself as an honest person.

The narrative conception of self is compatible with the idea that there is nothing metaphysically deep about the self. The narrative that I construct is just one of many different possible narratives that could be constructed from the same raw material of my life—my experiences, memories, interests, commitments, and so on. Whereas philosophers have traditionally tried to respond to the persistence problem by searching for something within those raw materials that unifies our self and explains our persistence, the narrative view sees the unity as something imposed from the outside—from a narrator. Thus, like the example of the ship in the beginning of this chapter, the narrative view views one’s identity as an extrinsic property (like the mere fact that the ship was always called “TS”) rather than as an intrinsic property. Perhaps a good analogy would be currency. Consider what makes a 100 dollar bill valuable. It certainly isn’t the paper an ink which constitutes the bill. Rather, it is the complex set of rules and institutions outside of the 100 dollar bill that gives it value. If you were to destroy that system (for example, if the government were overturned and all of the institutions like the Federal Reserve that bestow value on the 100 dollar bill ceased to exist), the 100 dollar bill would no longer have its value. It would simply be a piece of paper with some ink on it. Likewise, according to the narrative conception of the self, the fact that there is a persisting self depends on our ability to impose a story on our lives. If we lost that ability, there would be no persisting self although there would still be experiences, memories and thoughts. For the narrative view, the persisting self is an abstract entity that we construct from the raw materials of our lives and which, once constructed, exerts guidance on our lives.

One problem with the narrative view is that it defines the self too narrowly. If the existence of a persisting self requires a narrative arc with a beginning, middle, and end, then many individuals’ lives will lack this structure, for example, because their lives ended early. Such lives would seem lack any persisting self, if the narrative view is correct. Moreover, there are many people who have a sense of themselves as persisting through time although they don’t really have any grand narrative of their life. For this reason and others, some philosophers, such as Elisabeth Camp, have suggested thinking about our constructed identities not in the narrative, beginning-middle-end way, but rather thinking of ourselves as characters in an unfolding story whose end we don’t know yet. The main difference is that whereas the narrative conception holds one’s interpretation of their life hostage to the end of the story, the character conception doesn’t. Instead, what guides our interpretation of our lives is a “particular nexus of dispositions, memories, interests, and commitments.”[17] The interpretation that we create can also be constrained by information we glean about ourselves from other people, such as our friends.

6. Study questions

- True or false: The persistence question asks whether or not there exists a momentary awareness of ourselves as agents.

- True or false: There are two main types of answer to the persistence question.

- True or false: John Locke’s view of personal identity is a kind of psychological continuity view.

- True or false: According to Locke, if our DNA always stayed the same, this would be a good answer to the persistence question.

- True or false: DNA could serve as a good criterion of numerical identity.

- True or false: One of the most difficult problems for the psychological continuity account is the fission problem.

- True or false: The fact that we should fear torture to our body even if all of our psychological states have been transferred to a different body is supposed to provide support to the bodily continuity account of personal identity.

- True or false: According to Locke, “person” is a forensic term.

- True or false: Animalism is a type of bodily continuity account of personal identity.

- True or false: Dicephalic twins pose a problem for animalism.

- True or false: Dennett’s science fiction story suggests that a person can continue to persist despite having neither a brain nor a body.

- True or false: Narrative accounts of the self are compatible with the idea that there is no persisting self.

7. For deeper thought

- What does it mean to say that “identity is a transitive relationship”? Explain how Locke’s memory criterion conflicts with the idea that identity is transitive.

- Whereas Lockean accounts are interested in accounting for how persons persist, animalists think that we should be explaining how organisms persist. Think of an example where the organism continues to persist while the person doesn’t.

- Explain the sense which the narrative account of the self makes our identities external to us. How does this different from traditional accounts of the persistence of the self?

- How is sleep a problem for Locke’s memory criterion?

- Suppose that we say that the identity conditions of a self are simply the object that traces a continuous spatio-temporal path. What makes me the same person as I was when I was 10 years old is that the body of my 10 year old self and the body of my 43 year old self has traces a continuous, uninterrupted spatiotemporal path. Would psychological continuity theorists accept this account? Why or why not?

- Suppose that in Williams’s transfer scenarios we transfer our whole brain from one body to another. Does this change your answer of who will be tortured? Why or why not?

- Why might Williams’s transfer scenarios really prove that we identify with our bodily properties rather than with our psychological properties?

- This thought experiment is quite old—going back to Ancient Greece at least—but the first record of it we have in writing is from Plutarch. He writes: “The ship wherein Theseus and the youth of Athens returned had thirty oars, and was preserved by the Athenians down even to the time of Demetrius Phalereus, for they took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and stronger timber in their place, insomuch that this ship became a standing example among the philosophers, for the logical question of things that grow; one side holding that the ship remained the same, and the other contending that it was not the same.” ↵

- I say “human being” rather than “person” here because as we will see below, different answers to the persistence question may or may not focus on the identity of persons. “Human being” is a broader term which leaves open the question of personhood. For example, I have always been a human being, but (depending on one’s view) I may not have always possessed personhood (for example, when I was an infant) and I may continue to persist as a human being even if I am no longer a person (for example, if I lose all of my brain functioning). ↵

- Some philosophers have claimed not to have the sense that they are the same person from one moment to the next. David Hume famously claimed (A Treatise of Human Nature, book 1, part IV, section VI). that we did not have any awareness of a persisting self. And the Oxford philosopher Derek Parfit came to see one’s sense of identity is a kind of illusion and that it doesn’t really matter that we do not persist as persons—in fact, that it can actually have salutary effects on one’s ethical stance towards the world. More on this idea in the last part of the chapter. ↵

- John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, book 2, chapter 27. ↵

- Some philosophers would put this point in terms of “possible worlds.” You could say that there is a “nearby possible world” in which, say, Bill, who is merely asleep, could remember earlier episodes of his life (all you have to do is wake Bill up). In contrast, there is no nearby possible world in which Bob, who as severe Alzheimer’s, could be made to remember earlier episodes of his life. ↵

- This objection to the memory criterion of personal identity was originally raised by Thomas Reid in his Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man (essay 3, chapter 6), which was published in 1785. Reid says: "Suppose a brave officer to have been flogged when a boy at school, for robbing an orchard, to have taken a standard from the enemy in his first campaign, and to have been made a general inadvanced life : suppose also, which must be admitted to be possible, that, when he took the standard, he was conscious of his having been flogged at school, and that when made a general he was conscious of his taking the standard, but had absolutely lost the consciousness of his flogging. These things being supposed, it follows, from Mr. Locke's doctrine, that he who was flogged at school is the same person who took the standard, and that he who took the standard is the same person who was made a general. Whence it follows, if there be any truth in logic, that the general is the same person with him who was flogged at school. But the general's consciousness does not reach so far back as his flogging therefore, according to Mr. Locke's doctrine, he is not the person who was flogged. Therefore the general is, and at the same time is not, the same person with him who was flogged at school." ↵

- Williams, Bernard, 1970, “The Self and the Future,” The Philosophical Review, 79: 161-180. Reprinted numerous times/places. ↵

- Williams (1970), p. 162. ↵

- The question of the relationship between our brains and our consciousness is thorny philosophical question. Some philosophers think that consciousness reduces to brain processes while other thinks that consciousness cannot be strictly reduced to brain processes. For more on this topic, see the chapter in this textbook on the mind-body problem. ↵

- See the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry here: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/animalism/ ↵

- See McMahan, Jeff, 2002, The Ethics of Killing: Problems at the Margins of Life, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 32. ↵

- This was originally published in Dennett’s, Brainstorms (Bradford Books, 1978) and has been reprinted many times in different places. ↵

- That this was one of the things he was attempting to do in this piece was in fact confirmed to me by Dennett in personal correspondence (Snapchat—just kidding, email). ↵

- Aficionados of the heavy metal band Metallica will recognize this kind of situation as one portrayed in the song, “One.” ↵

- One excellent representation of the doctrine of anatta comes from the Buddhist text, The Questions of King Milinda (Book 2, chapter 1) in which the Buddhist sage, Nāgasena, explains to Milinda that just as a chariot is nothing in additions to all its parts, so the self is nothing in addition to all of its parts. ↵

- David Hume, 1739, A Treatise of Human Nature (book 1, part IV, section VI). ↵

- Elisabeth Camp, “Wordsworth’s Prelude, Poetic Autobiography, and Narrative Constructions of the Self.” ↵