3.4 Writing To Persuade

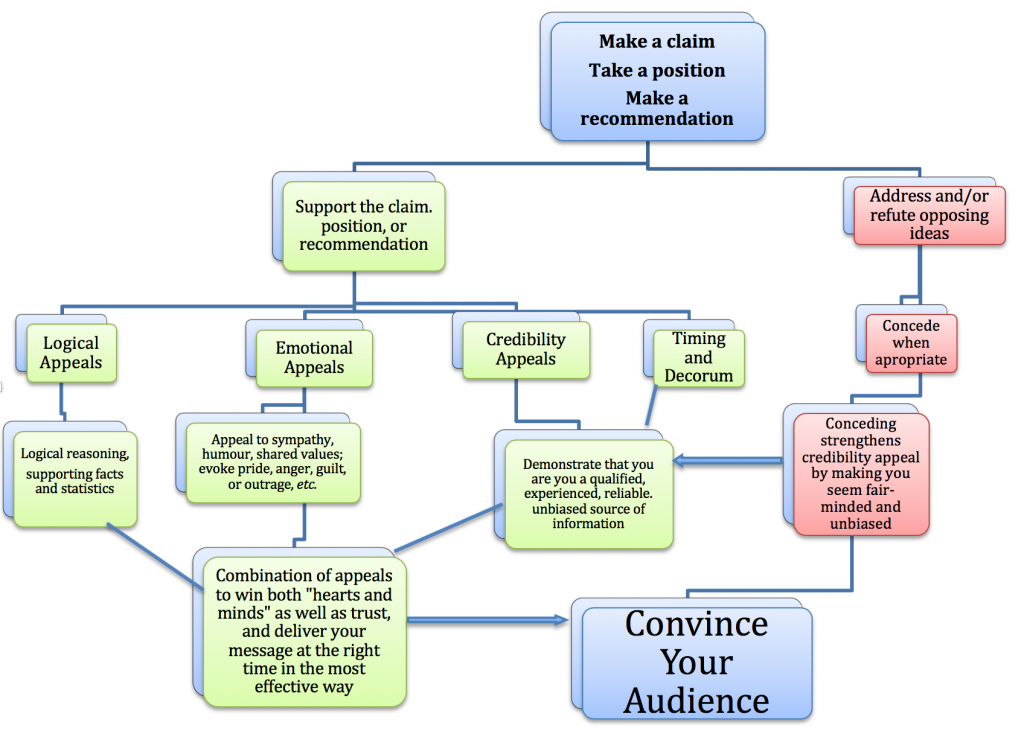

Sometimes, you may want to persuade your reader to take a particular action or position on an issue: It may be to accept a proposed change in procedure or an update in equipment, for example. Persuasion involves putting forth a compelling argument to reinforce or otherwise influence behaviour, action, and motivation. When persuading, you are drawing on a number of factors: ethics, emotion, facts, and timeliness. Each of these contributes to creating an argument that will move people to align with your goal. To be effective, you should consider how to make effective use of these elements of persuasion, often referred to as rhetorical appeals. The ancient Greek words are ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos (see Figure 3.4.1).

Let’s explore the rhetorical appeals further, along with how to avoid ad speak and ensure that you communications are ethical.

(Three Persuasive Appeals, 2017)

The Persuasive Toolkit

Ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos are key elements in the creation of effective persuasive messages. These used all together or singly function in specific ways to support and enhance your arguments.

- Ethos – Appeal to Credibility/Authority: This element of persuasion involves establishing your credibility, expertise, or authority for making the argument. What experience or expertise do you have? What knowledge or skills do you possess? What’s your role within the organization and/or in relation to the reader? Why should the reader trust you as a reliable, knowledgeable, authoritative, and ethical source of information? For example, when writing a proposal, establishing your credibility in your technical knowledge, skills, and leadership will help to inspire confidence in your abilities to do what you are offering to do.

- Pathos – Appeal to Emotion/Interest/Values: This element involves appealing to the emotions, values, and/or interests of the reader. How does your proposal benefit them? Why should they care about it? How does it relate to the goals of the organization? How can you build “common ground” with your reader? What will make your reader feel “good” about your project? How can you evoke emotions such as pride or outrage? Emotional appeal alone is used sparingly in technical communication unless it is for marketing purposes.

- Logos – Appeal to Reason/Logic: This element involves grounding your argument in logic, reason, and evidence. What evidence supports your claims? On what facts and data is your reasoning based? Arguments grounded in reason and evidence are often considered the strongest. Government organizations, companies, and various technologies and industries alike generally like to make “evidence-based decisions.” In a proposal, for example, providing evidence on the soundness of your proposed action would help to convince the reader that you have done your research and that your methods are grounded in facts.

- Kairos – Appeal to Timeliness/Appropriateness: Using this appeal means being aware of what is appropriate and timely in a given rhetorical situation. Sometimes, a well-crafted argument can fail because it comes at the wrong time. Kairos involves knowing what is “in” or “hot” right now, what is an important topic or issue, and how best to discuss it; knowing when it is the “right time” to broach a topic or propose an idea; knowing how to use the appropriate tone, level of formality and decorum for the specific situation. For example, having knowledge of current trends and innovations in a subject makes you able to speak to future probability.

Finding the appropriate blend of appeals is critical to making a successful argument. GenAI can help you to develop your persuasive arguments in a number of ways:

- It can assist in identifying gaps in logic and revising the arguments

- It can help identify bias and ensure that the argument falls within ethical boundaries

- It can create drafts of various appeals so that you can choose the ones that work the best for your purpose

Asking an LLM to Review Your Argument

First upload your text (paste it in the context window or upload a file) then use this prompt to ask the LLM to review your argument:

I am trying to persuade ________ to agree to __________. My argument is based on the rationale that __________, and I am using the following rhetorical appeals to create my argument [select the ones that apply: logos, pathos, ethos, kairos]. Please review my argument to determine if it is logical, if it contains bias, and if it is effectively constructed using the rhetorical appeals. If my argument is faulty, please highlight the flaws and suggest ways that I can improve the appeal.

Consider that when making your case, you will sometimes have to “win both hearts and minds”—so you’ll need to appeal to both emotions and logic. Assess the context and audience to plan your approach. Do whatever you can to show the reader that you are a trustworthy source of information, and present your argument at the most opportune time. Also be mindful of the word choice and tone so that you are presenting a persuasive argument that is constructive and conveys the appropriate tone for your intended audience, message, and purpose.

Knowledge Check

Fallacy-Free Persuasion

When creating persuasive arguments, fallacies must be avoided. The term fallacy refers to faulty reasoning. You can think of these as lapses or problems in your argument. They sometimes involve presenting irrelevant evidence to support claims, making “leaps” in reasoning that defy logic, and basing arguments on invalid assumptions, to name a few.

Sometimes, fallacies occur intentionally. In the worst cases, unethical influencers use fallacies to manipulate or deceive the receiver. Certainly, the intentional use of fallacies violates persuasion ethics, which destroys the credibility of the communicator and undermines relationships.

But most often, fallacies occur unintentionally. Perhaps you lack strong evidence to support a claim, and you stretch just a little too far in trying to make a case. Perhaps you might not have structured your argument and supporting evidence carefully enough, and the result is that your evidence doesn’t quite match your claims. Perhaps you are so passionate about your position that you let yourself get carried away and claim more than the evidence truly supports. Even when fallacies are unintended, they can still be harmful, as they can undermine the strength of your overall persuasive argument and raise concerns about your trustworthiness as a communicator.

In this section, you will learn how to deal with fallacies in persuasion.

Spot Common Fallacies

Spotting and correcting fallacies in your own writing will strengthen your skill as a persuasive communicator. Additionally, learning to identify fallacies will make you a more savvy receiver who can spot other people’s errors in reasoning. There are numerous types of fallacies. Here are some of the most common ones you may see in business communication messages.

Ad Hominem

The ad hominem (Latin for “to man”) fallacy is one in which someone attacks the person holding an opposing view rather than engaging with the substance of the argument. You can spot ad hominem attacks whenever an individual or even a group of individuals is insulted or name-called. You might even spot ad hominem attacks by frequent use of the words “they,” “you,” or “you people.”

Example: When persuading others to vote no on an initiative proposed by Joe: “Joe hasn’t had a good idea yet,” or, “Of course Joe would say that. He would do anything to avoid hard work.”

Instead: Focus on the merits and limitations of claims, arguments, and evidence, not on the person presenting them.

Bandwagon

The bandwagon fallacy is based on popularity: If many people like something or do something, it must be proper, effective, safe, etc. While popularity has a role in some technical decisions (for example, the popularity of a product may be important for projecting future sales), it should not be used to support all claims or as a substitute for other kinds of evidence. You can spot bandwagon appeals when communicators cite things like “most people,” “everyone,” or even present results of opinion polls.

Example: Deploying an artificial intelligence assistant to handle our customer service calls is a savvy business decision because all our competitors are doing it.

Instead: Base your decisions and arguments on how the idea applies to your specific and unique situation, not on what others are doing or thinking.

False Dilemma

The false dilemma fallacy occurs when receivers are presented with a simplified black-and-white choice between two positions that eliminates consideration of other middle-ground positions. You can spot false dilemma fallacies by looking for “either/or” wording. You might also be able to spot this fallacy if you can think of other reasonable options than those that are presented.

Example: We can either focus on reducing costs or we can prioritize sustainable sourcing.

Instead: When possible, explain the different options available and demonstrate that your recommendation is the best of all options. When there are too many different options to cover, be explicit that you are presenting only a few options but that other options are available.

Slippery Slope

The slippery slope fallacy is one in which the worst possible outcome is presented as the inevitable conclusion to taking a particular first step. It essentially denies the potentially complex sequence of steps and decisions that would have to be made to arrive at a particular conclusion. You can spot this fallacy by looking for “if/then” wording followed by an extreme logical leap. Sometimes, people will inadvertently alert you to this fallacy by prefacing their comments by saying, “It’s a slippery slope to….” While they may think they are warning you of inevitable negative outcomes, they are simultaneously pointing out their own fallacious reasoning.

Example: If we don’t adopt a remote work policy, we will be left with zero employees just in time for our busy season.

Instead: Focus your argument on realistic immediate and long-term consequences of the decision. Describe each step between the initial decision and the projected outcome and provide evidence to support those steps.

False Cause

The false cause fallacy (sometimes referred to as a correlation/causation fallacy) occurs when someone attempts to show that one phenomenon caused something else to happen without sufficient proof. Sometimes, evidence may show that two things happened at the same time or even that one followed the other. But just because two things are related, it doesn’t mean that one caused the other.

The false cause fallacy can be one of the most difficult to spot because it relies on close evaluation of evidence and strong critical thinking. You might ask, does this causal relationship make sense? Are there other phenomena that might have caused it? Does this causal relationship occur at other times or under other conditions?

Example: Our sales have dropped because of our competitor’s new advertising campaign.

Instead: Claim causation only after careful analysis of the evidence. Evaluate other plausible conditions. Rule out other conditions. You can also be explicit that even though there is a correlational relationship, it may or may not indicate causation.

Strawman

The strawman fallacy happens when someone distorts the opposing position in order to make it easy to refute. Someone using a strawman argument might mischaracterize, oversimplify, or exaggerate the opposing position. Then, after “winning” the easier argument, they consider the original argument decided. To spot this fallacy, you have to use your critical thinking and pay careful attention to any shift in the argument.

Example: When faced with a proposition to expand research and development efforts: Abandoning our current project and gambling on untested technology is a recipe for disaster. (The original proposal was for expansion, not for changing the project entirely.)

Instead: Make the effort to understand opposing positions and then present them fairly and honestly. Debate the matter at hand, even if it is difficult to do so.

Your Turn: Spot the Fallacies

Unfortunately, fallacies are all around you. One of the best ways to build your fallacy-spotting skills is with practice. Look online to find any social media forum where people are arguing about something. It can be a discussion forum on Facebook, Nextdoor, your local newspaper, or any other app or website with long threads of comments. Fallacies can be generated for nearly any topic. You don’t even have to seek anything overtly political or sensitive to find a passionate exchange. Sometimes, even conversations about trees and pets are enough to trigger debate.

Pick a thread and see how many fallacies you can spot.

Questions to Ponder

1. Which fallacies did you see the most?

2. How did people respond to the fallacies? Did they notice the fallacies? Did fallacies trigger different kinds of responses?

3. How could similar positions be advocated without fallacies?

Admit and Fix Mistakes

Despite your best efforts, there will be times when fallacies will find their way into your arguments. When that happens, you will need a plan to respond.

As described above, fallacies are introduced unintentionally most of the time. But that doesn’t mean that your receiver will automatically assume that your fallacy was unintentional. When fallacies appear in your argument, you run the risk of your receiver thinking that you intended to manipulate or deceive. So, the most important thing you can do is to restore trust and credibility immediately.

Therefore, when your receiver spots a fallacy, the best approach is to admit your mistake and fix it. Admitting your mistake could be as simple as saying, “You’re right, that doesn’t work,” “I agree, that doesn’t really follow,” or “I see what you’re saying.” Fixing your fallacies could involve any of a number of different strategies. For example, you could provide better evidence that directly supports your claim; adjust your claim to match the evidence; drop your claim if sufficient evidence does not exist; or concede your point if there is sufficient evidence to the contrary.

Making an effort to admit and fix your mistakes will go a long way to retaining and/or restoring your credibility with your receiver.

Asking an LLM to Check for Fallacies

First upload your text (paste it in the context window or upload a file) then use this prompt to ask the LLM to review your argument for fallacies:

I am trying to persuade ________ to agree to __________. My argument is based on the rationale that __________. I want to ensure that my argument does not contain any fallacies. Please review my argument and highlight any fallacies (ad hominem, bandwagon, false dilemma, slippery slope, false cause, and strawman) contained in it. If you find any fallacies, suggest how I can better express the argument.

Avoiding Ad-Speak

“Ad-Speak” refers to the kind of language often used in advertisements. Its aim is to convince consumers to buy something, whether they need it or not, hopefully without thinking too much about it. Because we hear this kind of rhetoric all the time, it easily becomes a habit to use it ourselves. We must break this habit when communicating in professional contexts.

Ad-Speak tends to use strategies such as

- emotional manipulation

- logical fallacies

- exaggeration or dishonesty

- vague claims

- incomplete or cherry-picked data

- biased viewpoints

- hired actors rather than professionals or experts as spokespeople

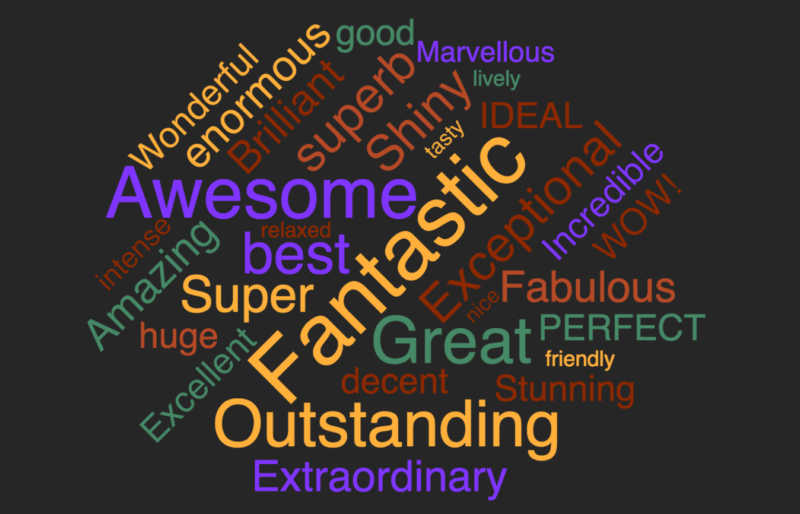

As a student in a technical program learning the specialized skills and developing the sense of social obligation needed to become a trusted professional, you should avoid using “sensational” words characteristic of marketing language. Instead, when trying to persuade your reader, make sure you use quantifiable, measurable descriptors and objective language in your writing. You cannot determine how many units of “excellence” something has, or its quantifiable amount of “awesomeness,” “fantastic-ness,” or “extraordinariness.” Describing something as “incredible” literally means it’s unbelievable. So avoid using these kinds of words shown in Figure 3.4.2.

Rather, find measurable terms like “efficiency” (in time or energy use), “effectiveness” at fulfilling a specific task, measurable benefits and/or costs, or even “popularity” as measured by a survey.

In technical writing, communicating ethically is critically important. Ethical communication involves communicating from a place of accountability, responsibility, integrity, and values. If you are communicating ethically, you are demonstrating respect for your reader, the organizations you work for, and the culture and context within which you work. You also foster fairness and trust through honesty. Failure to maintain integrity and ethics can result in consequences ranging from damage to reputation, loss of work, lawsuits, or even criminal charges.

This is precisely why many professional associations have guidelines that govern the ethical behaviour of their membership. Two such documents that offer good examples are the Canadian Information Processing Society’s (CIPS) Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct and the Ontario Association of Certified Engineering Technicians and Technologists (OACETT) Code of Ethics and Rules of Professional Conduct.

2. CODE OF ETHICS

Members of the Association recognize the precepts of personal integrity and professional competence as fundamental ethics, and as such each Member shall:

(a) hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public, the protection of the environment and the promotion of health and safety within the workplace;

(b) undertake and accept responsibility of professional assignments only when qualified by training or experience;

(c) provide an opinion on a professional subject only when it is founded upon adequate knowledge and honest conviction;

(d) act with integrity towards clients or employers, maintain confidentiality and avoid a conflict of interest but, where such conflict arises, fully disclose the circumstances without delay to the employer or client;

(e) uphold the principle of appropriate and adequate compensation for the performance of their work;

(f) keep informed to maintain proficiency and competence, to advance the body of knowledge within their discipline and further opportunities for the professional development of their associates;

(g) conduct themselves with fairness, courtesy and good faith toward clients, colleagues and others, give credit where it is due and accept, as well as give, honest and fair professional comment;

(h) present clearly to employers and clients the possible consequences if professional decisions or judgements are overruled or disregarded;

(i) report to the appropriate agencies any hazardous, illegal or unethical professional decisions or practices by fellow members or others; and

(j) promote public knowledge and appreciation of engineering and applied science technology and protect the Association from misrepresentation and misunderstanding.

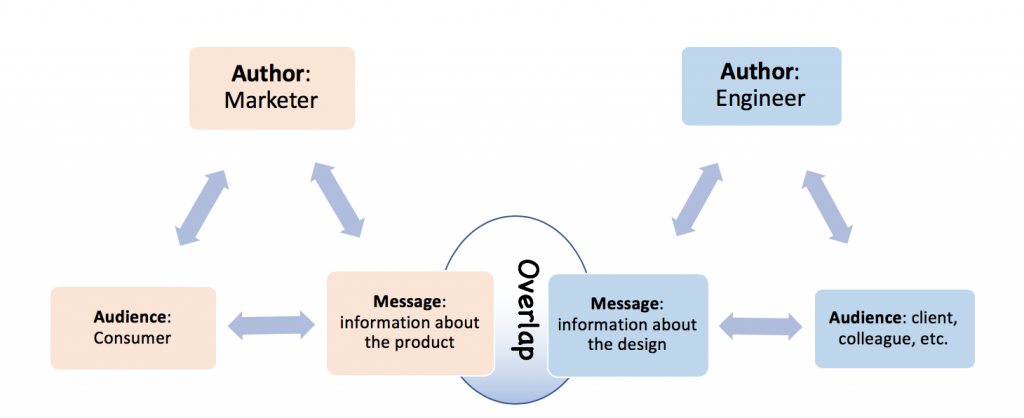

It is important to become familiar with such standards of practice and to consider how they impact communication practices. Remember that you are communicating in a professional context, and that comes with responsibility. Consider the different rhetorical situations diagrammed in Figure 3.4.3, one for a marketer and one for an engineer.

Clearly, there may be some overlap, but there will also be significant differences based on the needs and expectations of the audience and the kind of message being delivered. We hear marketing language so often that it is easy to fall into the habit of using it, even when it’s not appropriate. Make sure you are not using “ad-speak” when trying to persuade in a professional context.

Knowledge Check

Knowledge Check

All in all, carefully crafting your persuasive arguments will likely influence your audience to better understand if not agree with your position. Ensuring that you make effective use of logical appeals and remove logical fallacies as well as ad-speak from your content will make your arguments stronger, credible, and actionable.

The segment on Fallacy-Free Persuasion has been lightly adapted from Business Communication: Five Core Competencies by Kristen Lucas, Jacob D. Rawlins, and Jenna Haugen, 2023. CC by 4.0.

References

Chartered Professionals in Human Resources of Canada. (2016). Code of ethics and rules of professional conduct. https://cphr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/2016-Code-of-Ethics-CPHR-2.pdf

CIPS. (2018, June). CIPS code of ethics. Official Website of CIPS. https://cipsresources.ca/ethics/

Last, S. (2019). Technical writing essentials. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/

Lucas, K., Lucas, Rawlins, J. D., and Haugen, J. (2023). Strive for Fallacy-Free Persuasion – Business Communication: Five Core Competencies CC by 4.0.

OACETT. (n.d.). Code of ethics and rules of professional conduct. Ontario Association of Certified Engineering Technicians and Technologists. PDF. https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:6ed24f48-2a81-482d-9015-3728dba3ab42#pageNum=1

Ulmer, K. (2017). The three persuasive appeals: Logos, ethos, and pathos [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-oUfOh_CgHQ