1.5 Writing Processes

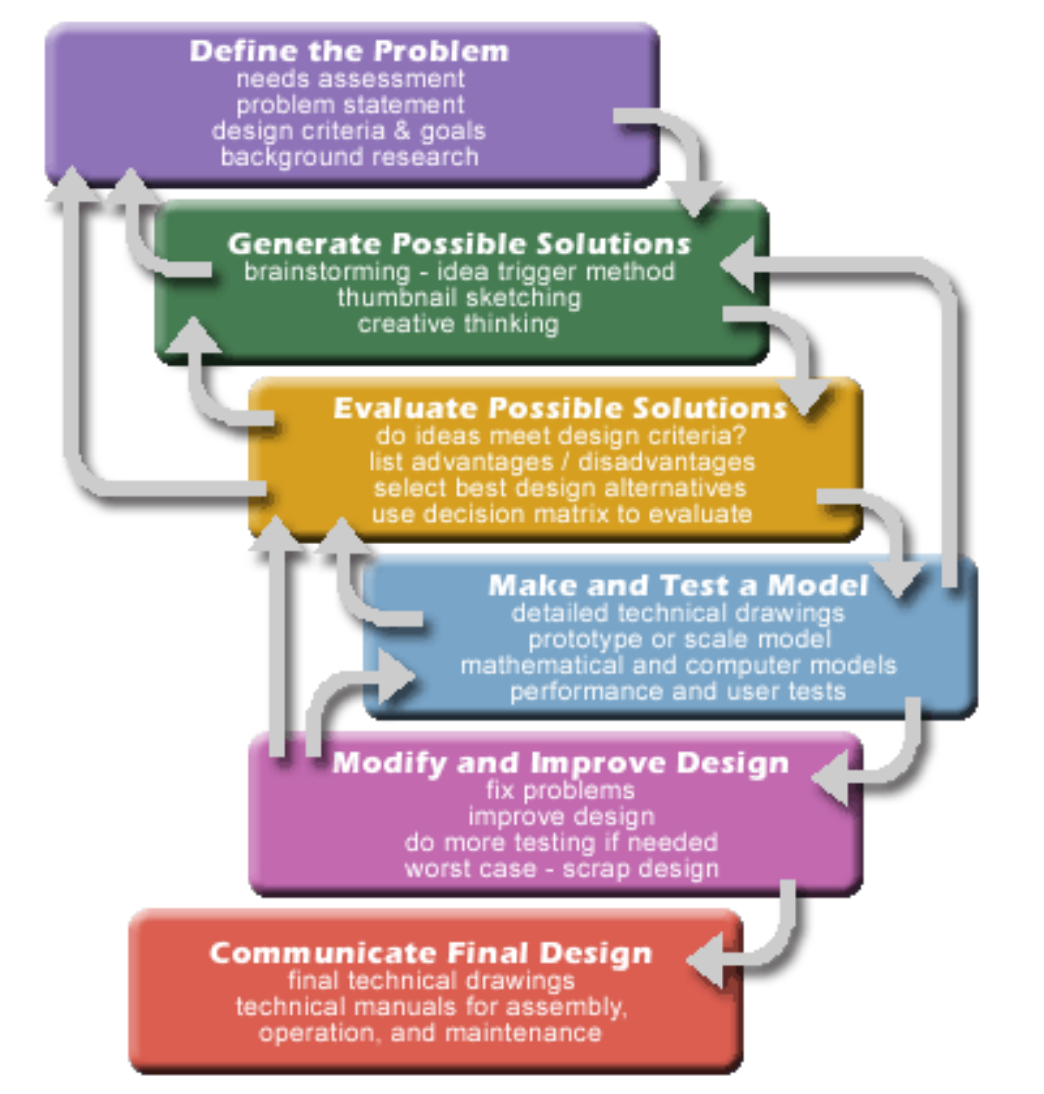

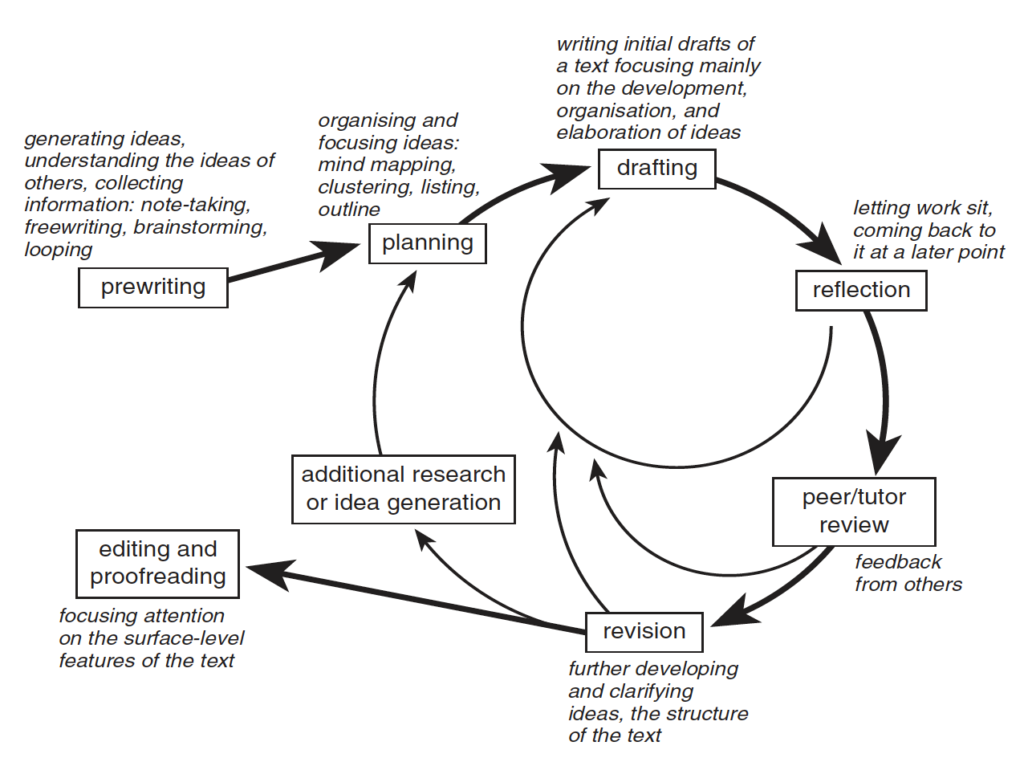

Just as we use design processes to creatively solve complex problems, we use writing processes to create complex documents. In both cases, there are steps or stages, but we don’t always proceed directly from one step to the next in a chronological manner. These processes are often iterative, meaning we might return to previous stages in the process from time to time. The more complex the task, the more iteration might be needed. Examine the Design Process (Figure 1.5.1) and Writing Process (Figure 1.5.2) diagrams below. What similarities and differences can you see in these two processes? How are they similar or different to your own processes?

You may have come across a writing process diagram before, and it may or may not have worked well for you. There is no single process that works for everyone in every situation. The key is to recognize the various steps in a typical writing process and figure out how to use or adapt them most effectively for your situation.

Knowledge Check: Review the video, 5 Steps of the Academic Writing Process, and answer the embedded questions.

You may have also come across the 40-20-40 writing process, which suggests that you should break up the amount of time you spend on the writing task into three distinct stages of planning, drafting and revising, and give each one a specific percentage of the time you have available.

With the increasing use of LLMs in the writing process, the ratio of time spent on planning, drafting and revising should be revised to more realistically represent the balance of AI-engaged and human-engaged time: Consider the 35-15-50 ratio.

35-15-50 AI-enhanced Writing Process

Stage 1 – Planning: Spend 35% of your time planning your document (task analysis, thinking, discussing, free-writing, researching, brainstorming, concept mapping, focusing ideas, outlining, etc.). In this phase, integrate LLM assistance with intentionality, clearly separating “just me” tasks from “LLM” tasks. For example, you should carefully think through the task at hand to narrow the focus of your work and determine the extent of research required and how the LLM and other genAI applications can assist. You should begin by conducting some research to familiarize yourself with key issues and topic areas, then integrate genAI research applications into the process to deepen your knowledge. You can then work interactively with the LLM to brainstorm ideas and generate outline options to get started on ideation.

Stage 2 – Drafting: Spend 15% of your time drafting your document. At this point, you can enlist the LLM through detailed prompting and with a solid outline to draft your message or document. As covered in Chapter 2.5 on prompting, the quality and detail in your prompt will determine how many times you will need to ask the LLM for revisions or improvements, so the more detail you include in your prompt the more efficient the process will be. Remember, the LLM output should always be treated as draft content to be carefully reviewed and revised by you, the human.

Stage 3 – Revising: Spend 50% of your time revising, editing, and proofreading. The work at this stage is intensive because LLMs are fallible machines, and you cannot rely on them to produce ready-to-go content. Your professional reputation and that of the organization you work for rely on accurate and complete messaging and documents. So engaging in a thorough review of the output before you put it in your documents is the only ethical thing to do. Your review should include the following:

- Checking for content alignment with your purpose

- Ensuring alignment with organizational values, such as diversity, inclusivity, and sustainability

- Corroborating all claims and refining them so they accurately represent the original intent

- Verifying all citations and ensuring that all claims are supported by accurate citations

- Adding details that the LLM would not have any way of discovering

- Editing for sentiment by adjusting the vocabulary so the tone meets the moment

More on integrating genAI applications into your process in Chapter 2.4.

These percentages are a helpful guideline, as they emphasize the need to allot significant time for revision, but don’t always work for all people in all situations (such as final exams). It also does not clearly account for the need to iterate; sometimes while revising your draft (Stage 3), you may have to go back to the planning stage (Stage 1) to do additional research, adjust your focus, or reorganize ideas to create a more logical flow. Writing, like any kind of design work, demands an organic and dynamic process.

As with the design process, the writing process must begin with an understanding of the problem you are trying to solve. In an educational context, this means understanding the assignment you’ve been given, the requirements of that assignment, the objectives you are meant to achieve, and the constraints you must work within (due dates, word limits, research requirements, etc.). This is often referred to as “Task Analysis.” In professional contexts, you must also consider who your intended reader(s) will be, why they will be reading this document, and what their needs are, as well as deadlines and documentation requirements.

Knowledge Check

EXERCISE 1.5.1 Planning your writing process

Consider an upcoming writing assignment or task you must complete. To avoid putting it off until the last minute (and possibly doing a poor job), try planning a writing process for this task, and build in milestones. Anticipate how long various sub-tasks and stages might take. Make sure to include time for “task and audience analysis” to fully understand what’s involved before you start. Consider the following:

- What is the purpose of the document? What are the specific requirements? Who will read it and why?

- How much planning is needed? What will this entail? Will you need to do research? Do you need to come up with a topic or focus, or has one been assigned to you?

- How complicated will the document be? Will it have several sections? Graphics? How much revision will be needed to perfect your document? Will you have time for a peer/tutor review?

You will be asked to complete project plans for some more involved assignments, which will help you plan your work and estimate the amount of time it will take you to complete it. For now, try using Seneca Libraries’ Assignment Calculator to see if it offers something similar to your planned writing process.

References

Curry, M.J. & Hewings, A. (2003). Approaches to teaching writing. In Teaching Academic Writing: A Toolkit for Higher Education. New York: Routledge. Used with permission.

Green Dot Consulting Group. (n.d.). Image. The design process. https://www.thegreendotgroup.com/process-improvement-tools-and-templates-resource-center/design-thinking-tools-and-templates/.

Scribbr. (2021). 5 steps of the academic writing process [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xM7sAD_oEDk