1.4 Case Studies: The Cost of Poor Communication

No one knows exactly how much poor communication costs business, industry and government each year, but estimates suggest billions. In fact, a recent estimate claims that the cost in the U.S. alone is close to $4 billion annually! (Bernoff, 2016). Poorly worded or inefficient emails, careless reading or listening to instructions, documents that go unread due to poor design, hastily presenting inaccurate information, sloppy proofreading — all of these examples result in inevitable costs. The problem is that these costs aren’t usually included on the corporate balance sheet at the end of each year, so often the problem remains unsolved.

(What is the Cost of Poor Communication, 2022)

Knowledge Check

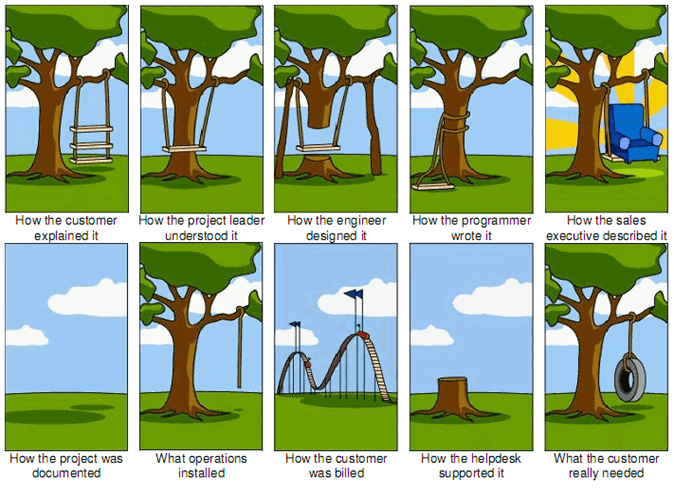

You may have seen the Project Management Tree Cartoon before (Figure 1.4.1); it has been used and adapted widely to illustrate the perils of poor communication during a project.

The waste caused by imprecisely worded regulations or instructions, confusing emails, long-winded memos, ambiguously written contracts, and other examples of poor communication is not as easily identified as the losses caused by a bridge collapse or a flood. But the losses are just as real—in reduced productivity, inefficiency, and lost business. In more personal terms, the losses are measured in wasted time, work, money, and ultimately, professional recognition. In extreme cases, losses can be measured in property damage, injuries, and even deaths.

CASE STUDY AND DISCUSSION: The Cost of Poor Communication

Read the article How Poorly Written Emails Cause Disasters and Cost Lives: 5 Questions for Carolyn Boiarsky contributed by Tim Ward (2017)

Read the article How Poorly Written Emails Cause Disasters and Cost Lives: 5 Questions for Carolyn Boiarsky contributed by Tim Ward (2017)

As a communications expert, I’m obsessed by what makes for effective communications. So I was both surprised and delighted to discover a new book that looks at miscommunication. Risk Communication and Miscommunication analyses some famous disasters, such as the Columbia Shuttle explosion and the Horizon BP blowout in the Gulf of Mexico. The author highlights how engineers, scientists and technical experts’ poorly written emails, memos and PowerPoint slides created chains of bad decisions that resulted in catastrophes. If technical experts would read this book and apply its principles, they could prevent future disasters and save lives. I interviewed the author, Carolyn Boiarsky, a professor of English at Purdue University Northwest-Calumet Campus, to find out more about her research:

Question 1: What was the role of miscommunication in the Columbia Shuttle disaster?

Answer: There were two major situations in which miscommunication occurred. The first occurred when an engineer offsite wrote a rambling email to the engineers who had been working 24/7 to figure out to what extent the tile had damaged the shuttle. The engineer came very close to figuring out what had probably happened but because he rambled on about personal issues at the beginning of the message, the engineers did not read it.

The second error occurred when the engineers were reporting their findings to NASA in a PowerPoint presentation. The mathematical model they had used to determine the extent of the damage was invalid for damage that was as large as this was but the engineers only indicated this at the bottom of the slide where few people would notice it.

Question 2: What was in an engineer’s email that led to the BP Deepwater Horizon blowout in the Gulf of Mexico?

Answer: One of the engineers on the rig wrote an email to his manager who was on land basically crying for help in making some controversial decisions about closing off the well. The manager responded to the engineer by indicating that he was going dancing that evening and would be in touch with the engineer the following day. The message from the engineer on the rig rambled, including personal information, so that the tone appeared to be a whine rather than a request for an immediate decision. The writer needed to recognize the reader’s psychological context: he had been receiving emails related to problems on the rig for several weeks. This one did not appear different from the others. In addition, the tone and rambling style of the writer’s message was similar to messages found on social media. Thus. the reader’s response was similar to one he might have written in response to a message on social media; he failed to recognize the difference. The engineer on the rig either needed to indicate at the very beginning of the message that this problem was different from the others, that the consequences could be more disastrous, and that the reader’s response was needed immediately or he needed to speak directly to the person via telephone rather than rely on electronic media to convey his message.

Question 3: After analyzing these fatal miscommunications, what’s your advice to scientists, engineers and other technical experts for communicating effectively?

Answer: All messages need to be reader-based. In other words, think of how the reader will read the message. A good rule of thumb is to start off immediately by (1) stating the purpose for the message, (2) providing a one-sentence summary of what the e-mail is about and (3) indicate the number of requests to which you need a response.

Question 4: Can you give an example from your book where technical experts communicated well and prevented a disaster?

Answer: When the Mississippi River was rising in 2011, the Army Corps of Engineers in the Kansas District Office realized that the Morganza Floodway might need to be opened to prevent flooding in New Orleans. If that were the case, the residents on the land that would be flooded when the Spillway opened would need to be evacuated along with any livestock. They would also need to remove all hazardous materials and waste that could leak into the water. The Corps recognized that potentially the action could anger the residents for being uprooted and frustrate them in terms of knowing when and how they would know that they would need to move.

To remind residents that they had been warned about the possibility of their land being flooded when they acquired their property as well as to alleviate residents’ anxiety over being uprooted and to motivate them to evacuate, if necessary, the Corps wrote two letters. The first, sent annually in January, reminded residents of their contract with the government that included their possible need to evacuate the area should there be a need to open the Floodway. The second was sent in late spring and got to the point immediately – their land might be flooded if the Mississippi River continued to rise. The letter provided residents with instructions on what to do and how they would be notified if the Floodway had to be opened. The letter also indicated that the damage they would sustain should they decide to remain would be considerable.

Question 5: What can corporations, governments, and other decision-making bodies do to improve the quality of their internal communications?

Answer:

For managers:

- Provide a safety-conscious environment.

- Ensure a non-threatening environment so that problems can be discussed without fear of retaliation.

- Provide complete explanations of potential or actual problems.

For Writers

- Always think of how your readers’ will read your message and write accordingly.

- Focus on a single purpose for each message.

- Include information readers not only want but may also need.

- Provide the most important information in the first paragraph.

Note:

- Carolyn Boiarsky, professor of English at Purdue University Northwest-Calumet Campus, specializes in technical communication. She’s the author of 3 books on communication, including Risk Communication and Miscommunication: Case Studies in Science, Technology, Engineering Government and Community Organizations.

- Tim Ward is the co-owner of Intermedia Communications Training and co-author of The Master Communicator’s Handbook – a resource for experts and thought leaders seeking to create meaningful change.

![]() Discuss the following questions in small groups and present your ideas to your group members:

Discuss the following questions in small groups and present your ideas to your group members:

- How did poorly written emails and communication contribute to the Columbia Shuttle disaster and the BP Deepwater Horizon blowout in the Gulf of Mexico? What key mistakes were made in each case?

- According to Carolyn Boiarsky, what are the key principles for technical experts to communicate effectively and avoid miscommunication? How can these principles be applied in various technical fields, especially aviation industry?

- Can you think of examples from your own experience or knowledge where miscommunication or poorly written messages led to negative consequences? How could these situations have been avoided or resolved?

- The author mentions a successful communication example from the Army Corps of Engineers during the Mississippi River flooding in 2011. What strategies did they use to effectively communicate with residents and prevent a disaster?

- How can corporations, governments, and other decision-making bodies improve the quality of their internal communications, based on the insights shared in the interview? Can you provide examples of organizations that have successfully implemented such strategies?

The following “case studies” show how poor communications can have real-world costs and consequences. For example, consider the “Comma Quirk” in the Rogers contract that cost $2 million (Robertson, 2006). Also, check out how a small error in spelling a company name cost £8.8 million (The Guardian, 2015). Or examine Tufte’s discussion (.pdf) of the failed PowerPoint presentation that attempted to prevent the Columbia Space Shuttle disaster (2001). Or you might want to read about how the failure of project managers and engineers to communicate effectively resulted in the deadly Hyatt Regency walkway collapse (McFadden, 2017). The case studies below offer a few more examples that might be less extreme, but much more common.

Knowledge Check

Review the Case Study 1 and 2 below. Answer that questions that follow each case study. Exercises adapted from T.M. Georges’ Analytical Writing for Science and Technology (1996).

CASE 1: The promising chemist who buried his results

Bruce, a research chemist for a major petrochemical company, wrote a dense report about some new compounds he had synthesized in the laboratory from oil-refining by-products. The bulk of the report consisted of tables listing their chemical and physical properties, diagrams of their molecular structure, chemical formulas and computer printouts of toxicity tests. Buried at the end of the report was casual speculation that one of the compounds might be a particularly effective insecticide.

Seven years later, the same oil company launched a major research program to find more effective but environmentally safe insecticides. After six months of research, someone uncovered Bruce’s report and his toxicity tests. A few hours of further testing confirmed that one of Bruce’s compounds was the safe, economical insecticide they had been looking for.

Unfortunately, Bruce had since left the company because he felt that the importance of his research was not being appreciated.

CASE 2: The unaccepted current regulator proposal

The Acme Electric Company worked day and night to develop a new current regulator designed to cut the electric power consumption in aluminum plants by 35%. They knew that, although the competition was fierce, their regulator could be produced more cheaply, was more reliable, and worked more efficiently than the competitors’ products.

The owner, eager to capture the market, personally but somewhat hastily put together a 120-page proposal and sent it to the three major aluminum manufacturers, recommending that their regulators be installed at all company plants.

She devoted the first 87 pages of the proposal to the mathematical theory and engineering design behind this new regulator, and the next 32 to descriptions of the new assembly line she planned to set up to produce regulators quickly. Buried in an appendix were the test results that compared her regulator’s performance with present models, and a poorly drawn graph showed how much the dollar savings would be.

Acme Electric didn’t get the contracts, despite having the best product. Six months later, the company filed for bankruptcy.

Now, in small groups, examine each “case” and determine the following:

- Define the rhetorical situation: Who is communicating to whom about what, how, and why? What was the goal of the communication in each case?

- Identify the communication error (poor task or audience analysis? Use of inappropriate language or style? Poor organization or formatting of information? Other?)

- Explain what costs/losses were incurred by this problem.

- Identify possible solutions or strategies that would have prevented the problem, and what benefits would be derived from implementing solutions or preventing the problem.

Present your findings in a brief, informal presentation to the class.

CASE 3: The instruction manual that scared customers away

As one of the first to enter the field of office automation, Sagatec Software, Inc. had built a reputation for designing high-quality and user-friendly database and accounting programs for business and industry. When they decided to enter the word-processing market, their engineers designed an effective, versatile, and powerful program that Sagatec felt sure would outperform any competitor.

To be sure that their new word-processing program was accurately documented, Sagatec asked the senior program designer to supervise the writing of the instruction manual. The result was a thorough, accurate and precise description of every detail of the program’s operation.

When Sagatec began marketing its new word processor, cries for help flooded in from office workers who were so confused by the massive manual that they couldn’t even find out how to get started. Then several business journals reviewed the program and judged it “too complicated” and “difficult to learn.” After an impressive start, sales of the new word-processing program plummeted.

Sagatec eventually put out a new, clearly written training guide that led new users step by step through introductory exercises and told them how to find commands quickly. But the rewrite cost Sagatec $350,000, a year’s lead in the market, and its reputation for producing easy-to-use business software.

CASE 4: One garbled memo – 26 baffled phone calls

Joanne supervised 36 professionals in 6 city libraries. To cut the costs of unnecessary overtime, she issued this one-sentence memo to her staff:

After the 36 copies were sent out, Joanne’s office received 26 phone calls asking what the memo meant. What the 10 people who didn’t call about the memo thought is uncertain. It took a week to clarify the new policy.

CASE 5: Big science — Little rhetoric

The following excerpt is from Carl Sagan’s book, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (Sagan, 1995) itself both a plea for and an excellent example of clear scientific communication:

The Superconducting Supercollider (SSC) would have been the preeminent instrument on the planet for probing the fine structure of matter and the nature of the early Universe. Its price tag was $10 to $15 billion. It was cancelled by Congress in 1993 after about $2 billion had been spent — a worst of both worlds outcome. But this debate was not, I think, mainly about declining interest in the support of science. Few in Congress understood what modern high-energy accelerators are for. They are not for weapons. They have no practical applications. They are for something that is, worrisomely from the point of view of many, called “the theory of everything.” Explanations that involve entities called quarks, charm, flavor, color, etc., sound as if physicists are being cute. The whole thing has an aura, in the view of at least some Congresspeople I’ve talked to, of “nerds gone wild” — which I suppose is an uncharitable way of describing curiosity-based science. No one asked to pay for this had the foggiest idea of what a Higgs boson is. I’ve read some of the material intended to justify the SSC. At the very end, some of it wasn’t too bad, but there was nothing that really addressed what the project was about on a level accessible to bright but skeptical non-physicists. If physicists are asking for 10 or 15 billion dollars to build a machine that has no practical value, at the very least they should make an extremely serious effort, with dazzling graphics, metaphors, and capable use of the English language, to justify their proposal. More than financial mismanagement, budgetary constraints, and political incompetence, I think this is the key to the failure of the SSC.

CASE 6: The co-op student who mixed up genres

Chris was simultaneously enrolled in a university writing course and working as a co-op student at the Widget Manufacturing plant. As part of his co-op work experience, Chris shadowed his supervisor/mentor on a safety inspection of the plant, and was asked to write up the results of the inspection in a compliance memo. In the same week, Chris’s writing instructor assigned the class to write a narrative essay based on some personal experience. Chris, trying to be efficient, thought that the plant visit experience could provide the basis for his essay assignment as well.

He wrote the essay first because he was used to writing essays and was pretty good at it. He had never even seen a compliance memo, much less written one, so was not as confident about that task. He began the essay like this:

On June 1, 2018, I conducted a safety audit of the Widget Manufacturing plant in New City. The purpose of the audit was to ensure that all processes and activities in the plant adhere to safety and handling rules and policies outlined in the Workplace Safety Handbook and relevant government regulations. I was escorted on a 3-hour tour of the facility by…

Chris finished the essay and submitted it to his writing instructor. He then revised the essay slightly, keeping the introduction the same, and submitted it to his co-op supervisor. He “aced” the essay, getting an A grade, but his supervisor told him that the report was unacceptable and would have to be rewritten – especially the beginning, which should have clearly indicated whether or not the plant was in compliance with safety regulations. Chris was aghast! He had never heard of putting the “conclusion” at the beginning. He missed the company softball game that Saturday so he could rewrite the report to the satisfaction of his supervisor.

Exercises adapted from T.M. Georges’ Analytical Writing for Science and Technology (1996).

Review the video below for a few suggestions on improving workplace communication.

(The Recipe for Great Communication, 2015)

References

Bernoff, J. (2016, October 16). Bad writing costs business billions. Daily Beast. https://www.thedailybeast.com/bad-writing-costs-businesses-billions?ref=scroll

Georges, T. M. (1996). Analytical writing for science and technology. https://www.scribd.com/document/96822930/Analytical-Writing

McFadden, C. (2017, July 4). Understanding the tragic Hyatt Regency walkway collapse. Interesting Engineering. https://interestingengineering.com/understanding-hyatt-regency-walkway-collapse

Robertson, G. (2006, August 6). Comma quirk irks Rogers. Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/comma-quirk-irks-rogers/article1101686/

Sagan, C. (1995). The demon-haunted world: science as a candle in the dark. New York, NY: Random House.

The £8.8m typo: How one mistake killed a family business. (28 Jan. 2015). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/law/shortcuts/2015/jan/28/typo-how-one-mistake-killed-a-family-business-taylor-and-sons

The Colin James Method. (2022). What is the cost of poor communication [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zTCXCpJ-CpU

The Latimer Group. (2015). The recipe to great communication [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFWsTsvJ8Xw

Tufte, E. (2001). The cognitive style of PowerPoint. https://www.inf.ed.ac.uk/teaching/courses/pi/2016_2017/phil/tufte-powerpoint.pdf

Ward, J. (2019, July 8). The project management tree swing cartoon, past and present. TamingData. https://www.tamingdata.com/2010/07/08/the-project-management-tree-swing-cartoon-past-and-present/. CC-BY-ND 4.0.

Ward, T. (2017, October 7). How poorly written emails cause disasters and cost lives: 5 questions for Carolyn Boiarsky. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/how-poorly-written-emails_b_12374770