2.3 Technical Communication is Transactional

McDonald Kyte

(Perkins, 2013) Image. From Adobe Stock [Vector] by Feodora / Education License – Standard Image

(Perkins, 2013) Image. From Adobe Stock [Vector] by Feodora / Education License – Standard Image

Communication models are frameworks that describe the process of communication. Over the years, various models have been developed to better understand how communication occurs between individuals and groups. These models can be broadly categorized into three types: transmission (linear), interaction, and transactional.

The transmission model and interaction model of communication differ from the transactional model in terms of the power and autonomy granted to participants, the assumed purpose of communication, and the factors considered relevant to a communication episode.

Transmission Model of Communication

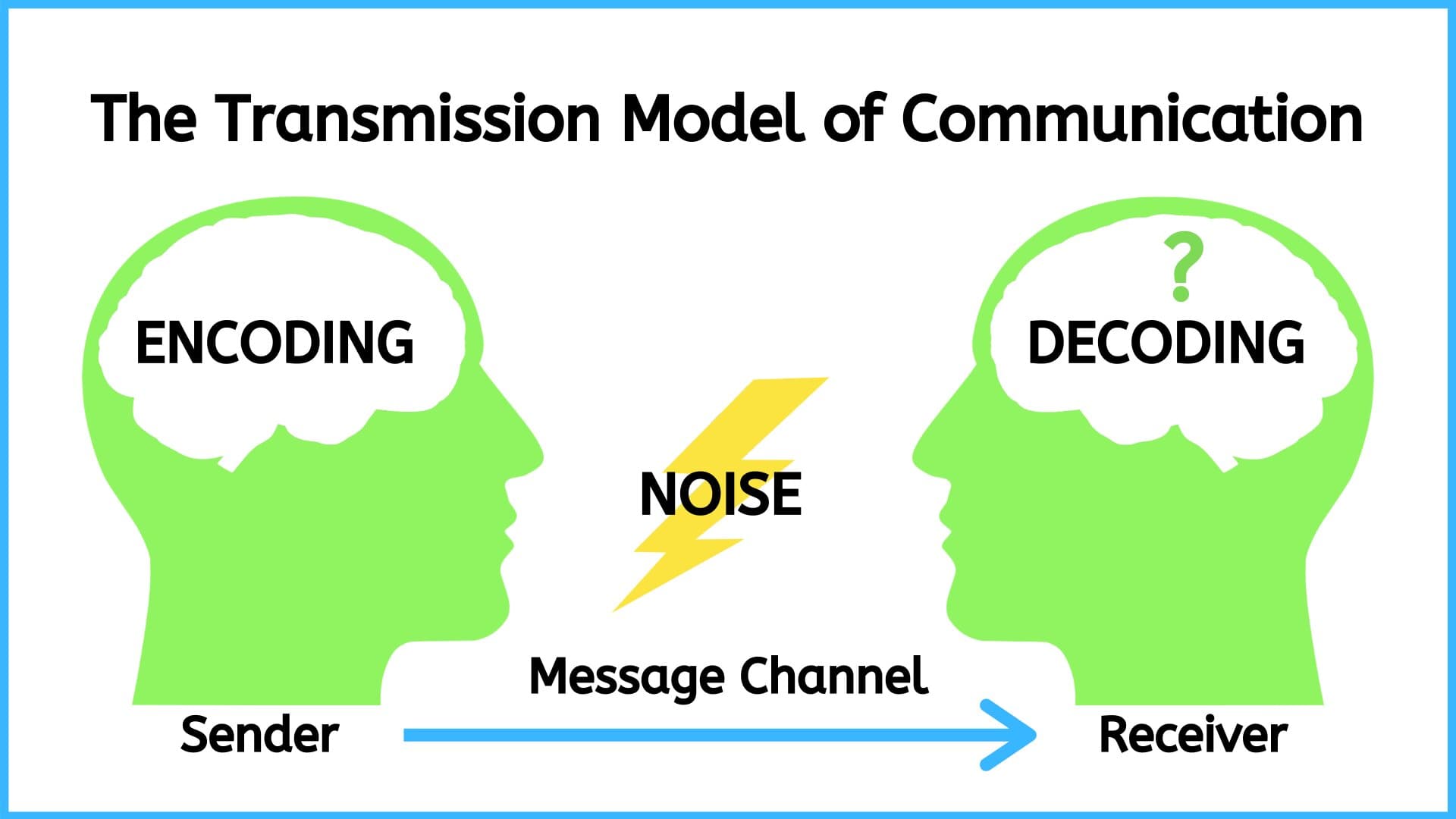

The transmission model of communication, Figure 2.3.1, (also called a sender approach) proposes that people are alternately senders and receivers (Shannon & Weaver, 1949). Senders transmit messages to receivers either face to face or through channels such as the telephone or computer. In terms of this model, physical noise (such as static, music, other voices, or loud machinery) may distort the message or how it is understood. As mentioned, one shortfall of this approach is that it tends to support an uneven balance of power. The person assumed to have the most valuable information is often given license to set the tone and terms of an interaction (Merkelsen, 2011).

Figure 2.3.1: The Transmission Model of Communication (Lapum et al., 2020)

Figure 2.3.1: The Transmission Model of Communication (Lapum et al., 2020)

Another limitation of the transmission model is that it depicts communication as the product of relatively detached and discrete components. Information, senders, and receivers are portrayed as distinct and separate entities, and the channel is assumed to be a neutral conduit for information (albeit one that is subject to the effects of noise). A common metaphor of the transmission model is tossing a ball back and forth. For the most part, we expect a ball to arrive at the receiver in the same form it left the sender, not to morph during the process. By the same token, senders and receivers are treated as independent agents.

As we will discuss later, which communication behaviours and channels are the most effective depends a great deal on the people, culture, and circumstances involved.

In sum, the greatest weakness of the transmission model is that it presents an overly simplistic, sender-oriented perspective on communication

Ogood-Schramm Interaction Model of communication

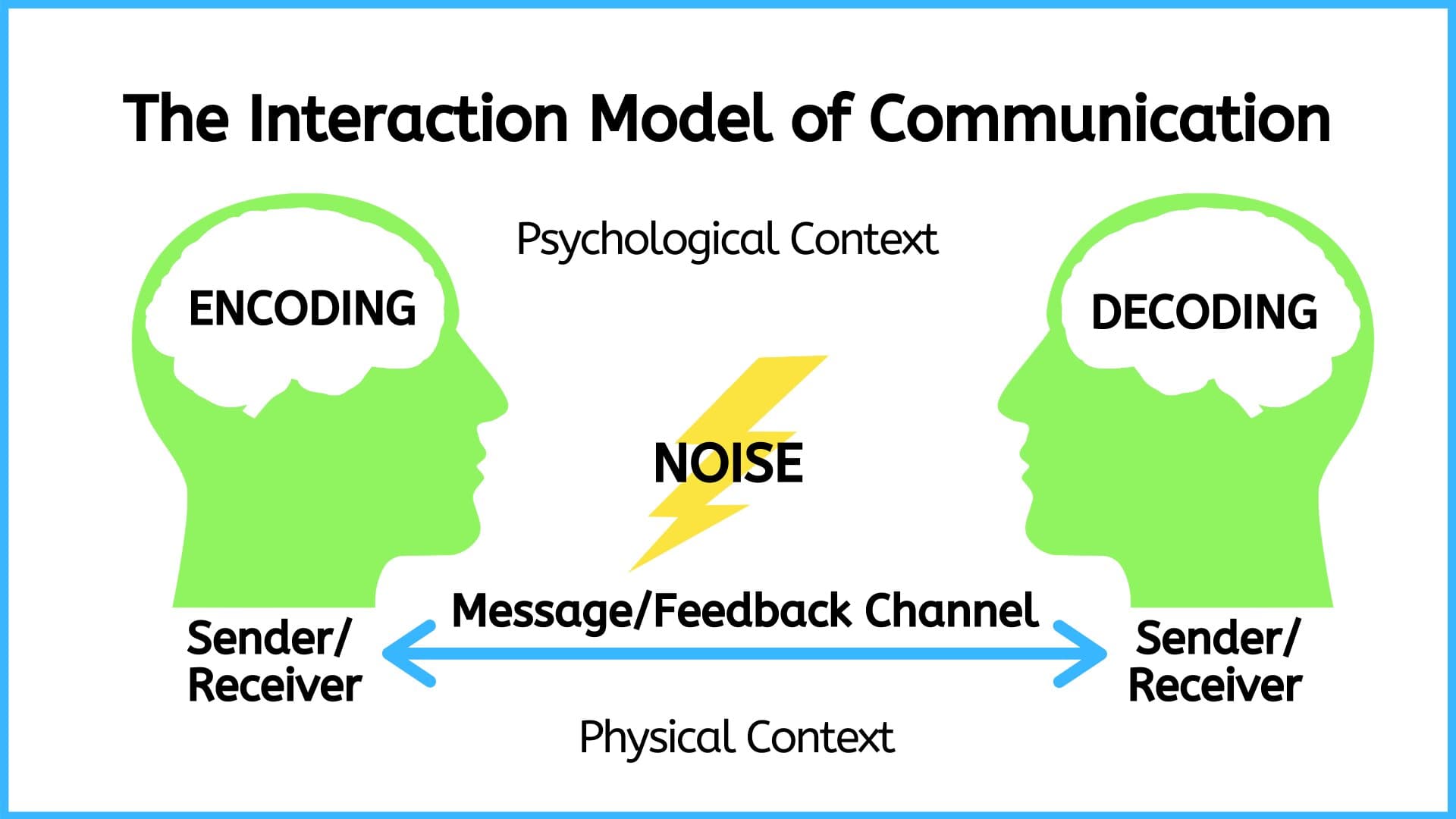

The interaction model of communication considers both the sender and the receiver responsible for the effectiveness of the communication. One of the major differences between the transmission model and the interaction model is the increased emphasis on feedback (Libretexts, 2021).

Figure 2.3.2 Transmission-Model-of-Communication (Lapum et al., 2020)

The encoder or carrier, decoder or listener, interpreter, or receiver, and message are components of the Osgood-Schramm communication model. According to this circular model of communication, information travels in both directions between the sender and the receiver during communication. Hence, once a person decodes a message, then they can encode it and send a message back to the sender. They could continue encoding and decoding into a continuous cycle. The entire process of communication is futile if the recipient cannot understand or decode the sender’s message. This model illustrates that feedback is a crucial component and it is cyclical. It also shows that communication is complex because it accounts for interpretation.

Nonetheless, the Osgood-Schramm model has major drawbacks. It cannot handle sophisticated communication procedures. This model does not account for many senders or receivers or the possibility of a multi-step communication process. It does not consider the possibility of unequal communication; this model frequently fails in scenarios involving different power dynamics among communications.

Transaction Model of communication

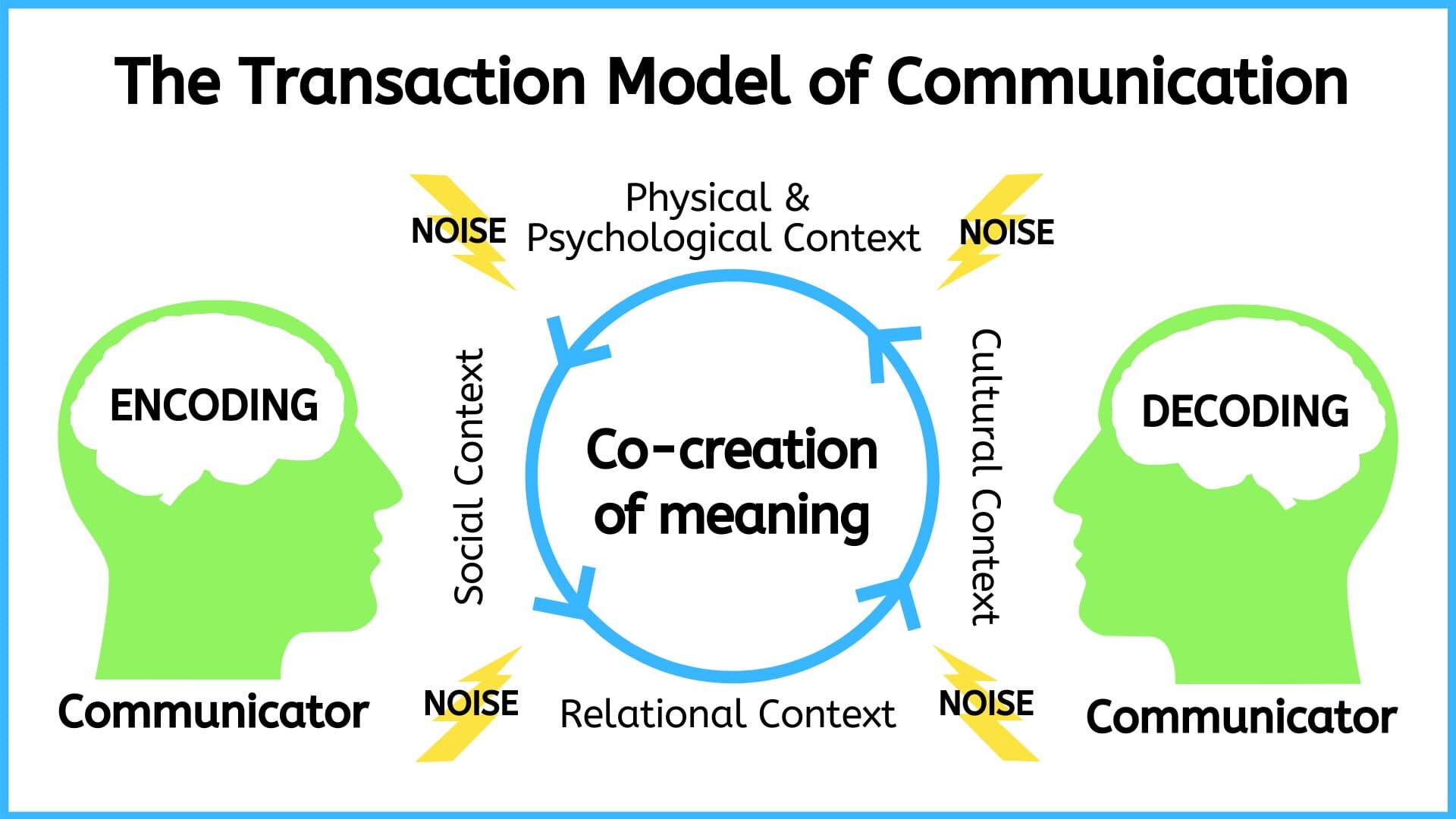

The transaction Model of communication (see Figure 1.5) differs from the Transmission Model in important ways, including the conceptualization of communication, the role of sender and receiver, and the role of context (Barnlund, 1970).

Figure 2.3.3 Transmission-Model-of-Communication

The transactional model of communication offers an alternative to the basic sender/receiver model by suggesting that individuals are both senders and receivers who are engaged in a continuously evolving communication process of mutual influence. In this model, the actions and words of one person affect others, and vice versa. Rather than just transmitting information, the emphasis is on creating shared meaning, highlighting the interactions “between people”. The transactional perspective encourages a more balanced sharing of power among individuals.

The transactional approach underscores the importance of being aware of cues, both verbal and nonverbal, that indicate how others are interpreting communication. Recognizing this, effective communicators do not treat messages casually. Instead, they carefully consider their words and actions based on how others receive them. They actively seek feedback, pay attention to feedback cues, and balance speaking with listening.

The transactional model also highlights that various environmental, cultural, and personal factors play a role in how communication is understood. Cultural differences extend to how different societies discuss professional issues, share information, expect the amount of details within a given context, and much more.

The transactional model considers “noise” as representing anything, whether internal (such as thoughts and feelings) or external (such as cultural context), that could hinder the shared understanding. However, as Wittenberg et al (2015) emphasize, the model does not suggest eliminating or minimizing these natural expressions of people’s identities. Instead, the transactional model encourages individuals to acknowledge cultural differences and seek mutually beneficial ways to respect diversity. This model emphasizes that communication is a collaborative process, constantly evolving as individuals and groups contribute to the meaning of the interaction.

Importance of Intercultural Communication

(McLain, n.d.) Image: From Adobe Stock [Vector] by Helga / Education License – Standard Image

(McLain, n.d.) Image: From Adobe Stock [Vector] by Helga / Education License – Standard Image

Edward Hall (1976), a pioneer in intercultural communication studies, made distinctions between cultures based on how much detail they include in their communication. In “high-context” cultures like China, Japan, India, South Africa, Argentina, Spain, the Middle East and others, communication tends to include limited amount of detail because both writers and readers assume that readers can infer specifics from their existing knowledge. High-context cultures often exhibit less-direct verbal and nonverbal communication, utilizing small communication gestures and reading more meaning into these less-direct messages. Here, successful communication relies on the contextual information readers bring to the message.

Conversely, in “low-context” cultures like Canada, the United States, and much of Northern Europe, writers assume readers have little contextual knowledge. In low-context cultures, communication must be more explicit, direct, and elaborate because individuals are not expected to know each other’s histories or backgrounds, and communication is not necessarily shaped by long-standing relationships between speakers. Thus, they provide extensive detail to cover every aspect of the topic thoroughly.

Understanding these cultural differences and adapting communications accordingly is crucial, especially when writing from one context to another or communicating with a culturally diverse audience. Anderson (2013) explains that in high-context cultures, readers might feel overwhelmed or annoyed by excessive details, as it implies they lack expected knowledge. On the other hand, in low-context cultures, it is assumed that readers are responsible for bringing very little contextual knowledge to a communication. Hence, low-context readers may feel neglected or confused if a writer does not provide sufficient detail or if the expected information is omitted as it may not align with their perceived needs. Refer to Chapter 4.4 Intercultural Communication for a detailed reading on intercultural communication.

In summary, the transmission model is linear and sender-focused, the interaction model emphasizes feedback and two-way communication, and the transactional model recognizes the simultaneous roles of both participants in shaping communication.

How to avoid Miscommunication

Communication is a fundamental human activity. However, can be complicated for several reasons. These complexities arise from the various factors involved in the process of transmitting and receiving messages such as physical and psychological noise, language barriers, complexity of the message, differences in perception and education, cultural and contextual differences, and quality of feedback.

Understanding the potential complications can help individuals and organizations develop strategies to improve communication effectiveness, such as choosing appropriate channels, being mindful of cultural differences, and providing clear feedback. Addressing these complexities is crucial for ensuring that messages are accurately transmitted and received, ultimately leading to better understanding and collaboration.

Exercise 2.3.1 Interactive Video

In the TED-Ed lesson “How Miscommunication Happens (And How to Avoid It)” Katherine Hampsten (2016) explores the intricate process of communication, explains how miscommunication often arises due to differences in personal experiences, emotions, and cultural backgrounds, and provides strategies that can enhance communication effectiveness and reduce misunderstandings.

Watch the video:

If the video does not work, click the YouTube link or copy and paste the link into a new tab: https://youtu.be/gCfzeONu3Mo

Now that you have watched the video, answer the following questions or discuss them in small groups.

Finally, reflect on the following questions:

- What are the perceptual filters that affect how you communicate? Can you identify at least three?

- How do these filters help or harm how you interpret communication?

- Why is feedback crucial in the communication process? Share a situation where feedback helped you understand or clarify a message.

- Have you ever encountered a situation where cultural differences led to miscommunication? How did you handle it, and what did you learn from that experience?

- How has technology affected the way we communicate? Discuss both the advantages and challenges technology presents in preventing miscommunication.

OUTLINING YOUR COMMUNICATION’S GOALS – A guide for technical communication

PURPOSE

- What is the purpose of your communication?

- What outcome do you want your communication to achieve?

- Who is your audience (decision-makers, experts/advisers, or implementers or all of them)?

CREATING A USEFUL COMMUNICATION

- What task will your communication help your reader perform?

- What information does your reader want? (What questions will your reader ask?)

- How will your reader search for the information? (May use more than one strategy.)

____ Sequential reading from beginning to end

____ Reading for key points

____ Reference reading

____ Other (describe)

- How will your reader use the information?

____ Compare alternatives (What will be the points of comparison?)

____ Determine how the information will affect them (or the organization)

____ Perform a procedure (following instructions step by step)

____ Other (describe)

CREATING A PERSUASIVE COMMUNICATION

- What is your reader’s attitude toward your subject? What do you want it to be?

- What is your reader’s attitude toward you? What do you want it to be?

- What is your reader’s attitude toward your organization? What do you want it to be?

READER’S PROFILE

- Position/Job within the organization

- Primary audience (decision maker), secondary audience (experts or advisers), or implementers

- Familiarity with the content (topic, problem, issue) of your communication

- Familiarity with specialized terminology and jargon

- Personal characteristics you should consider.

- Cultural characteristics you should consider.

CONTEXT

- What features of the context may affect the way your reader reads your communication?

- What expectations, regulations, or other factors constrain the way you can write?

Adapted from Technical Communication: A readers-centered approach, Anderson (2013)

References

Anderson, P. V. (2013). Technical communication. Cengage Learning.

Barnlund, D. C. (1970). A transactional model of communication. In K. K. Sereno & C. C. Mortensen (Eds.), Foundations of communication theory (pp. 83–92). Harper and Row.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Garden City, NY: Anchor.

Lapum, E. B. J., St-Amant, O., Hughes, M., & Garmaise-Yee, J. (2020, August 14). Transmission model of communication. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.library.torontomu.ca/communicationnursing/chapter/transmission-model-of-communication/

Libretexts. (2021, August 6). 2.4: Models of Interpersonal Communication. Social Sci LibreTexts. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Courses/Pueblo_Community_College/Interpersonal_Communication_-_A_Mindful_Approach_to_Relationships_(Wrench_et_al.)/02%3A_Overview_of_Interpersonal_Communication/2.04%3A_Models_of_Interpersonal_Communication:~:text=Osgood%2DSchramm’s%20model%20of%20communication,decoding%20into%20a%20continuous%20cycle.

McLain, K. B. (n.d.). Working Effectively with Home Care Clients. Pressbooks. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/home-health-aide/chapter/working-effectively-with-home-care-clients/

Merkelsen H. Risk communication and citizen engagement: What to expect from dialogue. J Risk Res. 2011;14(5):631–645.

Perkins, L. (2013). Communication: A Modern Illusion. Retrieved from http://purl.flvc.org/fsu/fd/FSU_migr_uhm-0204

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois

Wittenberg, E., Ferrell, B. R., Goldsmith, J., Smith, T., Ragan, S. L., & Handzo, G. (2015). Textbook of Palliative Care Communication. Oxford University Press, USA.