Chapter 8: Communication

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the communication process.

- Compare and contrast different types of communication.

- Compare and contrast different communication channels.

- Understand and learn to overcome barriers to effective communication.

- Understand the role listening plays in communication.

- Learn how verbal and nonverbal communication can carry different meanings among cultures.

You’ve Got Mail…and You’re Fired! The Case of RadioShack

No one likes to receive bad news, and few like to give it. In what is heralded as one of the biggest human resources blunders of 2006, one company found a way around the discomfort of firing someone face-to-face. A total of 400 employees at the Fort Worth, Texas, headquarters of RadioShack Corporation (NYSE: RSH) got the ultimate e-mail message early one Tuesday morning. The message simply said, “The work force reduction notification is currently in progress. Unfortunately, your position is one that has been eliminated.” Company officials argued that using electronic notification was faster and allowed more privacy than breaking the news in person, and additionally, those employees who were laid off received generous severance packages. Organizational consultant Ken Siegel disagrees, proclaiming, “The bottom line is this: To almost everyone who observes or reads this, it represents a stupefying new low in the annals of management practice.” It’s unclear what, if any, the long-term effect will be for RadioShack. It isn’t just RadioShack that finds it challenging to deal with letting employees go. Terminating employees can be a painful job for many managers. The communication that takes place requires careful preparation and substantial levels of skill. BusinessWeek ethics columnist, Bruce Weinstein, suggests that anyone who is involved with communicating with downsized employees has an ethical responsibility to do it correctly, which includes doing it in person, doing it privately, giving the person your full attention, being honest but sensitive, and not rushing the person. Some organizations outsource the job of letting someone go to “terminators” who handle this difficult task for them. In fact, Up in the Air, the 2009 movie starring George Clooney that was nominated for six Oscars, chronicles changes at a workforce reduction firm and highlights many of these issues.

Downsizing has been referred to using many euphemisms (language that softens the sound of the word) for termination. Here are just a few ways to say you’re about to lose your job without saying you’ve been fired:

- Career alternative enhancement program

- Career-change opportunity

- Dehiring staff

- Downsizing employment

- Employee reduction activities

- Implementing a skills mix adjustment

- Negative employee retention

- Optimizing outplacement potential

- Rectification of a workforce imbalance

- Redundancy elimination

- Right-sizing employment

- Vocation relocation policy

Regardless of how it’s done or what it’s called, is downsizing effective for organizations? Jeffrey Pfeffer, a faculty member at Stanford and best-selling author, argues no:

“Contrary to popular belief, companies that announce layoffs do not enjoy higher stock prices than peers—either immediately or over time. A study of 141 layoff announcements between 1979 and 1997 found negative stock returns to companies announcing layoffs, with larger and permanent layoffs leading to greater negative effects. An examination of 1,445 downsizing announcements between 1990 and 1998 also reported that downsizing had a negative effect on stock-market returns, and the negative effects were larger the greater the extent of the downsizing. Yet another study comparing 300 layoff announcements in the United States and 73 in Japan found that in both countries, there were negative abnormal shareholder returns following the announcement.”He further notes that evidence doesn’t support the idea that layoffs increase individual company productivity either: “A study of productivity changes between 1977 and 1987 in more than 140,000 U.S. companies using Census of Manufacturers data found that companies that enjoyed the greatest increases in productivity were just as likely to have added workers as they were to have downsized” (Hollon, 2006; Joyce, 2006; Pfeffer, 2006; Weinstein, 2008).

8.2 Understanding Communication

Communication is vital to organizations—it’s how we coordinate actions and achieve goals. It is defined in Webster’s dictionary as a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behaviours. We know that 50% to 90% of a manager’s time is spent communicating (Schnake et al., 1990), and communication ability is related to a manager’s performance (Penley et al., 1991). In most work environments, a miscommunication is an annoyance—it can interrupt workflow by causing delays and interpersonal strife. But, in some work arenas, like operating rooms and airplane cockpits, communication can be a matter of life and death.

So, just how prevalent is miscommunication in the workplace? You may not be surprised to learn that the relationship between miscommunication and negative outcomes is very strong. Data suggest that deficient interpersonal communication was a causal factor in approximately 70% to 80% of all accidents over the last 20 years.

Poor communication can also lead to lawsuits. For example, you might think that malpractice suits are filed against doctors based on the outcome of their treatments alone. But a 1997 study of malpractice suits found that a primary influence on whether or not a doctor is sued is the doctor’s communication style. While the combination of a bad outcome and patient unhappiness can quickly lead to litigation, a warm, personal communication style leads to greater patient satisfaction. Simply put, satisfied patients are less likely to sue.

In business, poor communication costs money and wastes time. One study found that 14% of each workweek is wasted on poor communication (Armour, 1998). In contrast, effective communication is an asset for organizations and individuals alike. Effective communication skills, for example, are an asset for job seekers. A recent study of recruiters at 85 business schools ranked communication and interpersonal skills as the highest skills they were looking for, with 89% of the recruiters saying they were important (Alsop, 2006). On the flip side, good communication can help a company retain its star employees. Surveys find that when employees think their organizations do a good job of keeping them informed about matters that affect them and when they have access to the information they need to do their jobs, they are more satisfied with their employers. So can good communication increase a company’s market value? The answer seems to be yes. “When you foster ongoing communications internally, you will have more satisfied employees who will be better equipped to communicate with your customers effectively,” says Susan Meisinger, president and CEO of the Society for Human Resource Management. Research finds that organizations that can improve their communication integrity also increase their market value by as much as 7% (Meisinger, 2003). We will explore the definition and benefits of effective communication in our next section.

The Communication Process

Communication fulfills three main functions within an organization, including coordination, the transmission of information, and sharing of emotions and feelings. All these functions are vital to a successful organization. The coordination of effort within an organization helps people work toward the same goals. Transmitting information is a vital part of this process. Sharing emotions and feelings bonds teams and unites people in times of celebration and crisis. Effective communication helps people grasp issues, build rapport with coworkers, and achieve consensus. So, how can we communicate effectively? The first step is to understand the communication process.

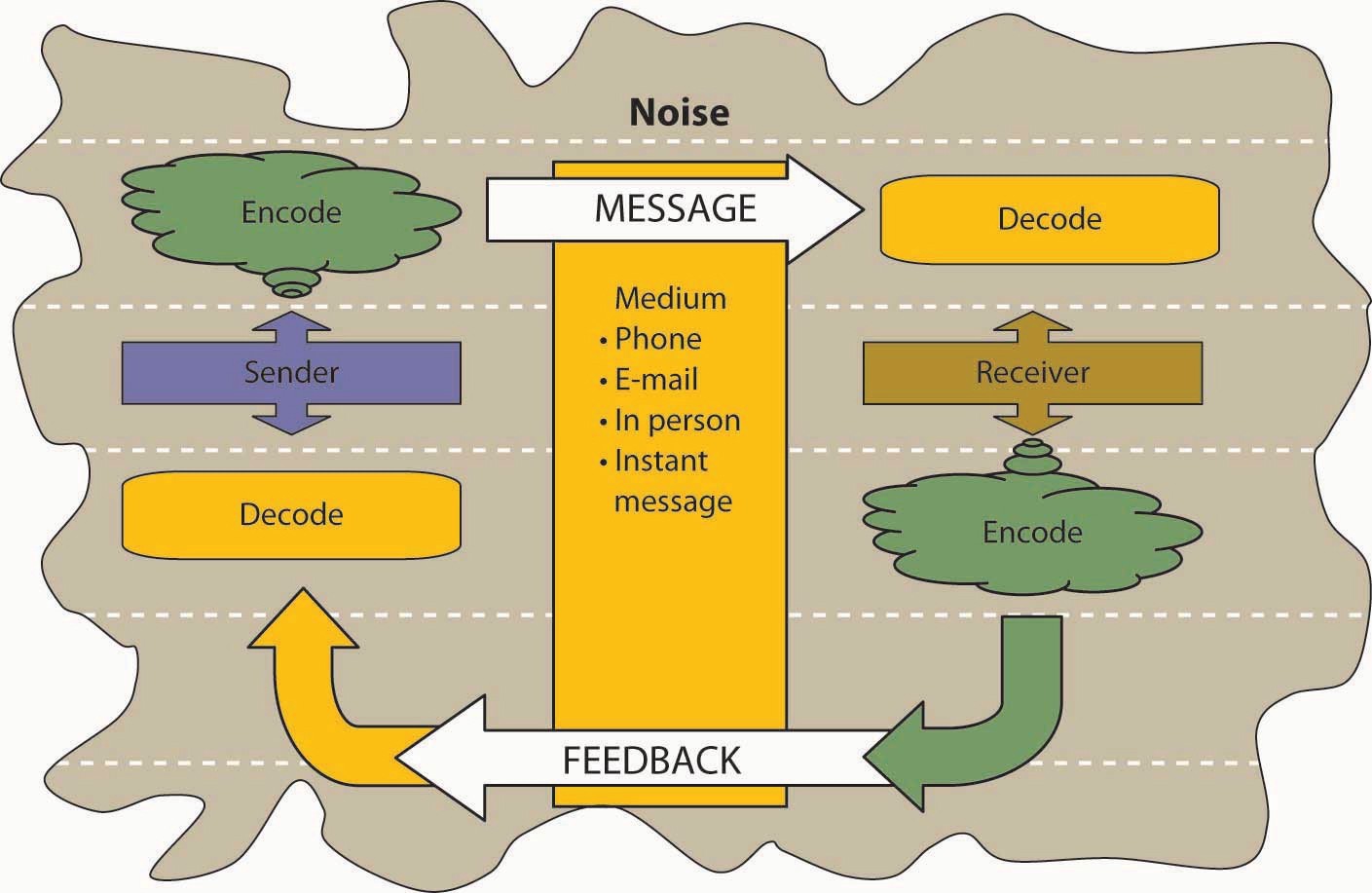

We all exchange information with others countless times each day by phone, e-mail, the printed word, and of course, in person. Let us take a moment to see how a typical communication cycle works using this as a guide.

A sender, such as a boss, coworker, or customer, originates the message with a thought. For example, the boss’s thought could be: “Get more printer toner cartridges!”

The sender encodes the message, translating the idea into words.

The boss may communicate this thought by saying, “Hey you guys, let’s order more printer toner cartridges.”

The medium of this encoded message may be spoken words, written words, or signs. The receiver is the person who receives the message.

The receiver decodes the message by assigning meaning to the words.

In this example, our receiver, Bill, has a to-do list a mile long. “The boss must know how much work I already have,” the receiver thinks. Bill’s mind translates his boss’s message as, “Could you order some printer toner cartridges, in addition to everything else I asked you to do this week…if you can find the time?”

The meaning that the receiver assigns may not be the meaning that the sender intended because of factors such as noise. Noise is anything that interferes with or distorts the message being transformed. Noise can be external in the environment (such as distractions), or it can be within the receiver. For example, the receiver may be extremely nervous and unable to pay attention to the message. Noise can even occur within the sender: The sender may be unwilling to take the time to convey an accurate message, or the words that are chosen can be ambiguous and prone to misinterpretation.

Picture the next scene. The place: a staff meeting. The time: a few days later. Bill’s boss believes the message about printer toner has been received.

“Are the printer toner cartridges here yet?” Bill’s boss asks.

“You never said it was a rush job!” Bill protests.

“But!”

“But!”

Miscommunications like these happen in the workplace every day. We’ve seen that miscommunication does occur in the workplace, but how does miscommunication happen? It helps to think of the communication process. The series of arrows pointing the way from the sender to the receiver and back again can, and often do, fall short of their target.

8.3 Communication Barriers

Barriers to Effective Communication

The biggest single problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

– George Bernard Shaw

Filtering

Filtering is the distortion or withholding of information to manage a person’s reactions. Some examples of filtering include a manager keeping a division’s negative sales figures from a superior, in this case, the vice president. The old saying, “Don’t shoot the messenger!” illustrates the tendency of receivers to vent their negative response to unwanted messages to the sender. A gatekeeper (the vice president’s assistant, perhaps) who doesn’t pass along a complete message is also filtering. Additionally, the vice president may delete the e-mail announcing the quarter’s sales figures before reading it, blocking the message before it arrives.

As you can see, filtering prevents members of an organization from getting the complete picture of a situation. To maximize your chances of sending and receiving effective communications, it’s helpful to deliver a message in multiple ways and to seek information from multiple sources. In this way, the impact of any one person’s filtering will be diminished.

Since people tend to filter bad news more during upward communication, it is also helpful to remember that those below you in an organization may be wary of sharing bad news. One way to defuse this tendency to filter is to reward employees who convey information upward, regardless of whether the news is good or bad.

Here are some of the criteria that individuals may use when deciding whether to filter a message or pass it on:

- Past experience: Were previous senders rewarded for passing along news of this kind in the past, or were they criticized?

- Knowledge and perception of the speaker: Has the receiver’s direct superior made it clear that “no news is good news?”

- Emotional state, involvement with the topic, and level of attention: Does the sender’s fear of failure or criticism prevent the message from being conveyed? Is the topic within the sender’s realm of expertise, increasing confidence in the ability to decode the message, or is the sender out of a personal comfort zone when it comes to evaluating the message’s significance? Are personal concerns impacting the sender’s ability to judge the message’s value?

Once again, filtering can lead to miscommunications in business. Listeners translate messages into their own words, each creating a unique version of what was said (Alessandra, 1993).

Selective Perception

Small things can command our attention when we’re visiting a new place—a new city or a new company. Over time, however, we begin to make assumptions about the environment based on our past experiences. Selective perception refers to filtering what we see and hear to suit our own needs. This process is often unconscious. We are bombarded with too much stimuli every day to pay equal attention to everything, so we pick and choose according to our own needs. Selective perception is a time-saver and a necessary tool in a complex culture. But it can also lead to mistakes.

Think back to the example conversation between the person asked to order more toner cartridges and his boss earlier in this chapter. Since Bill found the to-do list from his boss to be unreasonably demanding, he assumed the request could wait. (How else could he do everything else on the list?) The boss, assuming that Bill had heard the urgency of her request, assumed that Bill would place the order before returning to previously stated tasks. Both members of this organization were using selective perception to evaluate the communication. Bill’s perception was that the task could wait. The boss’s perception was that a timeframe was clear, though unstated. When two selective perceptions collide, a misunderstanding occurs.

Information Overload

Messages reach us in countless ways every day. Some messages are societal—advertisements that we may hear or see in the course of our day. Others are professional—e-mails, memos, and voice mails, as well as conversations with our colleagues. Others are personal—messages from and conversations with our loved ones and friends.

Add these together, and it’s easy to see how we may be receiving more information than we can take in.

This state of imbalance is known as information overload, which occurs “when the information processing demands on an individual’s time to perform interactions and internal calculations exceed the supply or capacity of time available for such processing” (Schick, Gordon, & Haka, 1990). Others note that information overload is “a symptom of the high-tech age, which is too much information for one human being to absorb in an expanding world of people and technology. It comes from all sources, including TV, newspapers, and magazines as well as wanted and unwanted regular mail, e-mail, and faxes. It has been exacerbated enormously because of the formidable number of results obtained from Web search engines.” Other research shows that working in such a fragmented fashion significantly impacts efficiency, creativity, and mental acuity (Overholt, 2001).

Going back to our example of Bill, let’s say he’s in his office on the phone with a supplier. While he’s talking, he hears the chime of his e-mail alerting him to an important message from his boss. He’s scanning through it quickly while still on the phone when a coworker pokes her head into his office, saying Bill’s late for a staff meeting. The supplier on the other end of the phone line has just given him a choice among the products and delivery dates he requested. Bill realizes he missed hearing the first two options, but he doesn’t have time to ask the supplier to repeat them all or to try reconnecting with him at a later time. He chooses the third option—at least he heard that one, he reasons, and it seemed fair. How good was Bill’s decision amidst all the information he was processing at the same time?

Workplace Gossip

The informal gossip network known as the grapevine is a lifeline for many employees seeking information about their company (Kurland & Pelled, 2000). Researchers agree that the grapevine is an inevitable part of organizational life. Research finds that 70% of all organizational communication occurs at the grapevine level (Crampton, 1998). Employees trust their peers as a source of information, but the grapevine’s informal structure can be a barrier to effective communication from the managerial point of view. Its grassroots structure gives it greater credibility in the minds of employees than information delivered through official channels, even when that information is false. Some downsides of the office grapevine are that gossip offers politically minded insiders a powerful tool for disseminating communication (and self-promoting miscommunications) within an organization. In addition, the grapevine lacks a specific sender, which can create a sense of distrust among employees: Who is at the root of the gossip network? When the news is volatile, suspicions may arise as to the person or person behind the message. Managers who understand the grapevine’s power can use it to send and receive messages of their own. They can also decrease the grapevine’s power by sending official messages quickly and accurately should big news arise.

Gender Differences in Communication

Men and women work together every day, but their different styles of communication can sometimes work against them. Generally speaking, women like to ask questions before starting a project, while men tend to “jump right in.” A male manager who’s unaware of how most women communicate their readiness to work may misperceive a ready employee as not being prepared.

Another difference that has been noticed is that men often speak in sports metaphors, while many women use their home as a starting place for analogies. Women who believe men are “only talking about the game” may be missing out on a chance to participate in a division’s strategy and opportunities for teamwork and “rallying the troops” for success (Krotz).

“It is important to promote the best possible communication between men and women in the workplace,” notes gender policy advisor Dee Norton, who provided the above example. “As we move between the male and female cultures, we sometimes have to change how we behave (speak the language of the other gender) to gain the best results from the situation. Successful organizations of the future are going to have leaders and team members who understand, respect, and apply the rules of gender culture appropriately” (CDR Dee Norton, 2008).

As we have seen, differences in men’s and women’s communication styles can lead to misunderstandings in the workplace. Being aware of these differences, however, can be the first step in learning to work with them instead of around them. Keep in mind that men tend to focus more on competition, data, and orders in their communications, while women tend to focus more on cooperation, intuition, and requests. Both styles can be effective in the right situations, but understanding the differences is the first step in avoiding misunderstandings.

Poor Listening

The greatest compliment that was ever paid to me was when one asked me what I thought and attended to my answer.

– Henry David Thoreau

A sender may strive to deliver a message. But the receiver’s ability to listen effectively is equally vital to successful communication. The average worker spends 55% of their workdays listening. Managers listen up to 70% of each day. Unfortunately, listening doesn’t lead to understanding in every case.

From several different perspectives, listening matters. Former Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca lamented, “I only wish I could find an institute that teaches people how to listen. After all, a good manager needs to listen at least as much as he needs to talk” (Iacocca & Novak, 1984). Research shows that listening skills were related to promotions (Sypher, Bostrom, & Seibert, 1989).

Listening matters. Listening takes practice, skill, and concentration. Alan Gulick, a Starbucks Corporation spokesperson, believes better listening can improve profits. If every Starbucks employee misheard one $10 order each day, their errors would cost the company a billion dollars annually. To teach its employees to listen, Starbucks created a code that helps employees taking orders hear the size, flavor, and use of milk or decaffeinated coffee. The person making the drink echoes the order aloud.

How Can You Improve Your Listening Skills?

Cicero said, “Silence is one of the great arts of conversation.” How often have we been in a conversation with someone else when we are not listening but itching to convey our portion? This behaviour is known as “rehearsing.” It suggests the receiver has no intention of considering the sender’s message and is preparing to respond to an earlier point instead. Effective communication relies on another kind of listening: active listening.

Active listening can be defined as giving full attention to what other people are saying, taking time to understand the points being made, asking questions as needed, and not interrupting at inappropriate times (O*NET Resource Center). Active listening creates a real-time relationship between the sender and receiver by acknowledging the content and receipt of a message. As we’ve seen in the Starbucks example above, repeating and confirming a message’s content offers a way to confirm that the correct content is flowing between colleagues. The process creates a bond between coworkers while increasing the flow and accuracy of messaging.

Becoming a More Effective Listener

As we’ve seen above, active listening creates a more dynamic relationship between a receiver and a sender. It strengthens personal investment in the information being shared. It also forges healthy working relationships among colleagues by making speakers and listeners equally valued members of the communication process.

Many companies offer public speaking courses for their staff, but what about “public listening”? Here are some more ways you can build your listening skills by becoming a more effective listener and banishing communication freezers from your discussions.

- Start by stopping. Take a moment to inhale and exhale quietly before you begin to listen. Your job as a listener is to receive information openly and accurately.

- Don’t worry about what you’ll say when the time comes. Silence can be a beautiful thing.

- Join the sender’s team. When the sender pauses, summarize what you believe has been said. “What I’m hearing is that we need to focus on marketing as well as sales. Is that correct?” Be attentive to physical as well as verbal communications. “I hear you saying that we should focus on marketing, but the way you’re shaking your head tells me the idea may not really appeal to you—is that right?”

- Don’t multitask while listening. Listening is a full-time job. It’s tempting to multitask when you and the sender are in different places, but doing that is counterproductive. The human mind can only focus on one thing at a time. Listening with only part of your brain increases the chances that you’ll have questions later, ultimately requiring more of the speaker’s time. (And when the speaker is in the same room, multitasking signals a disinterest that is considered rude.)

- Try to empathize with the sender’s point of view. You don’t have to agree, but can you find common ground (Barrett, 2006; Ten tips: Active listening, 2007)?

Communication Freezers

Communication freezers put an end to effective communication by making the receiver feel judged or defensive. Typical communication stoppers include criticizing, blaming, ordering, judging, or shaming the other person. Some examples of things to avoid saying include the following:

1. Telling the other person what to do:

- “You must…”

- “You cannot…”

2. Threatening with “or else” implied:

- “You had better…”

- “If you don’t…”

3. Making suggestions or telling the other person what they ought to do:

- “You should…”

- “It’s your responsibility to…”

4. Attempting to educate the other person:

- “Let me give you the facts.”

- “Experience tells us that…”

5. Judging the other person negatively:

- “You’re not thinking straight.”

- “You’re wrong.”

6. Giving insincere praise:

- “You have so much potential.”

- “I know you can do better than this.”

7. Psychoanalyzing the other person:

- “You’re jealous.”

- “You have problems with authority.”

8. Making light of the other person’s problems by generalizing:

- “Things will get better.”

- “Behind every cloud is a silver lining.”

9. Asking excessive or inappropriate questions (Tramel & Reynolds, 1981; Communication stoppers).

8.4 Different Types of Communication and Channels

Types of Communication

There are three types of communication including: verbal communication involving listening to a person to understand the meaning of a message, written communication, in which a message is read; and nonverbal communication, involving observing a person and inferring meaning. Let’s start with verbal communication, which is the most common form of communication.

Verbal Communication

Verbal communications in business take place over the phone or in person. The medium of the message is oral. Let’s return to our printer cartridge example. This time, the message is being conveyed from the sender (the manager) to the receiver (an employee named Bill) by telephone. We’ve already seen how the manager’s request to Bill (“Buy more printer toner cartridges!”) can go awry. Now let’s look at how the same message can travel successfully from sender to receiver.

Manager (speaking on the phone): “Good morning Bill!”

(By using the employee’s name, the manager is establishing a clear, personal link to the receiver.) Manager: “Your division’s numbers are looking great.”

(The manager’s recognition of Bill’s role in a winning team further personalizes and emotionalizes the conversation.)

Manager: “Our next step is to order more printer toner cartridges. Would you place an order for 1,000 printer toner cartridges with Jones Computer Supplies? Our budget for this purchase is $30,000, and the printer toner cartridges need to be here by Wednesday afternoon.” (The manager breaks down the task into several steps. Each step consists of a specific task, time frame, quantity, or goal.)

Bill: “Sure thing! I’ll call Jones Computer Supplies and order 1,000 more printer toner cartridges, not exceeding a total of $30,000, to be here by Wednesday afternoon.”

(Bill, a model employee, repeats what he has heard. This is the feedback portion of the communication. Feedback helps him recognize any confusion he may have had hearing the manager’s message. Feedback also helps the manager hear if she has communicated the message correctly.)

Storytelling is an effective form of verbal communication that serves an important organizational function by helping to construct common meanings for individuals within the organization. Stories can help clarify key values and also help demonstrate how certain tasks are performed within an organization. Story frequency, strength, and tone are related to higher organizational commitment (McCarthy, 2008). The quality of the stories is related to the ability of entrepreneurs to secure capital for their firms (Martens, Jennings, & Devereaux, 2007).

While the process may be the same, high-stakes communications require more planning, reflection, and skill than normal day-to-day interactions at work. Examples of high-stakes communication events include asking for a raise or presenting a business plan to a venture capitalist. In addition to these events, there are also many times in our professional lives when we have crucial conversations, which are defined as discussions in which not only are the stakes high, but also the opinions vary. Emotions run strong (Patterson et al., 2002). One of the most consistent recommendations from communications experts is to work toward using “and” instead of “but” when communicating under these circumstances. In addition, be aware of your communication style and practice being flexible; it is under stressful situations that communication styles can become the most rigid.

Written Communication

In contrast to oral and verbal communications, written business communications are printed messages. Examples of written communications include memos, proposals, e-mails, letters, training manuals, and operating policies. They may be printed on paper or appear on the screen. Written communication is often asynchronous. That is, the sender can write a message that the receiver can read at any time, unlike a conversation that is carried on in real-time. Written communication can also be read by many people (such as all employees in a department or all customers). It’s a “one-to-many” communication, as opposed to a one-to-one conversation. There are exceptions, of course: A voicemail is an oral message that is asynchronous. Conference calls and speeches are oral one-to-many communications, and e-mails can have only one recipient or many.

Normally, verbal communication takes place in real-time. Written communication, by contrast, can be constructed over a longer period of time. It also can be collaborative. Multiple people can contribute to the content of one document before that document is sent to the intended audience.

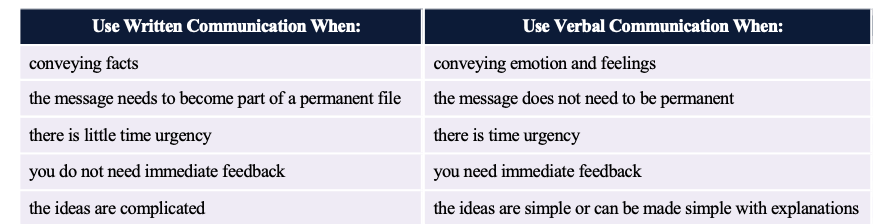

Verbal and written communications have different strengths and weaknesses. In business, the decision to communicate verbally or in written form can be a powerful one. As we’ll see below, each style of communication has particular strengths and pitfalls. When determining whether to communicate verbally or in writing, ask yourself: Do I want to convey facts or feelings? Verbal communications are a better way to convey feelings. Written communications do a better job of conveying facts.

Picture a manager making a speech to a team of 20 employees. The manager is speaking at a normal pace. The employees appear interested. But how much information is being transmitted? Probably not as much as the speaker believes. The fact is that humans listen much faster than they speak. The average public speaker communicates at a speed of about 125 words a minute, and that pace sounds fine to the audience. (In fact, anything faster than that probably would sound unusual. To put that figure in perspective, someone having an excited conversation speaks at about 150 words a minute.) Based on these numbers, we could assume that the audience has more than enough time to take in each word the speaker delivers, which creates a problem. The average person in the audience can hear 400 to 500 words a minute (Lee & Hatesohl). The audience has more than enough time to hear. As a result, their minds may wander.

As you can see, oral communication is the most often used form of communication, but it is also an inherently flawed medium for conveying specific facts. Listeners’ minds wander. It’s nothing personal—in fact, it’s a completely normal psychological occurrence. In business, once we understand this fact, we can make more intelligent communication choices based on the kind of information we want to convey.

Nonverbal Communication

What you say is a vital part of any communication. Surprisingly, what you don’t say can be even more important. Research shows that nonverbal cues can also affect whether or not you get a job offer. Judges examining videotapes of actual applicants were able to assess the social skills of job candidates with the sound turned off. They watched the rate of gesturing, time spent talking, and formality of dress to determine which candidates would be the most socially successful on the job (Gifford, Ng, & Wilkinson, 1985). Research also shows that 55% of in-person communication comes from nonverbal cues such as facial expressions, body stances, and tone of voice. According to one study, only 7% of a receiver’s comprehension of a message is based on the sender’s actual words, 38% is based on paralanguage (the tone, pace, and volume of speech), and 55% is based on nonverbal cues (body language) (Mehrabian, 1981). To be effective communicators, our body language, appearance, and tone must align with the words we’re trying to convey. Research shows that when individuals are lying, they are more likely to blink more frequently, shift their weight, and shrug (Siegman, 1985).

A different tone can change the perceived meaning of a message. For example, imagine that you’re a customer interested in opening a new bank account. At one bank, the bank officer is dressed neatly. She looks you in the eye when she speaks. Her tone is friendly. Her words are easy to understand yet professional sounding. “Thank you for considering Bank of the East Coast. We appreciate this opportunity and would love to explore ways that we can work together to help your business grow,” she says with a friendly smile. At the second bank, the bank officer’s tie is stained. He looks over your head and down at his desk as he speaks. He shifts in his seat and fidgets with his hands. His words say, “Thank you for considering Bank of the West Coast. We appreciate this opportunity and would love to explore ways that we can work together to help your business grow,” but he mumbles his words, and his voice conveys no enthusiasm or warmth. Which bank would you choose? The speaker’s body language must match his or her words. If a sender’s words and body language don’t match—if a sender smiles while telling a sad tale, for example—the mismatch between verbal and nonverbal cues can cause a receiver to dislike the sender actively.

Following are a few examples of nonverbal cues that can support or detract from a sender’s message.

Body Language

A simple rule of thumb is that simplicity, directness, and warmth convey sincerity. Sincerity is vital for effective communication. In some cultures, a firm handshake, given with a warm, dry hand, is a great way to establish trust. A weak, clammy handshake might convey a lack of trustworthiness. Gnawing one’s lip conveys uncertainty. A direct smile conveys confidence.

Newly conducted research by Amy Cuddy (2012) from Harvard University has found that not only can body language impact others’ perception of us, but it can also impact our own perception of ourselves! This Ted Talk below describes the research and the outcome: https://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are?language=en

Eye Contact

In business, the style and duration of eye contact vary greatly across cultures. In the United States, looking someone in the eye (for about a second) is considered a sign of trustworthiness.

Facial Expressions

The human face can produce thousands of different expressions. Experts have decoded these expressions as corresponding to hundreds of different emotional states (Ekman, Friesen, & Hager, 2008). Our faces convey basic information to the outside world. Happiness is associated with an upturned mouth and slightly closed eyes; fear with an open mouth and wide-eyed stare. Shifty eyes and pursed lips convey a lack of trustworthiness. The impact of facial expressions in conversation is instantaneous. Our brains may register them as “a feeling” about someone’s character. For this reason, it is important to consider how we appear in business as well as what we say. The muscles of our faces convey our emotions. We can send a silent message without saying a word. A change in facial expression can change our emotional state. Before an interview, for example, if we focus on feeling confident, our face will convey that confidence to an interviewer. Adopting a smile (even if we’re feeling stressed) can reduce the body’s stress levels.

Posture

The position of our body relative to a chair or other person is another powerful silent messenger that conveys interest, aloofness, professionalism, or lack thereof. Head up, back straight (but not rigid) implies an upright character. In interview situations, experts advise mirroring an interviewer’s tendency to lean in and settle back in a seat. The subtle repetition of the other person’s posture conveys that we are listening and responding.

Touch

The meaning of a simple touch differs between individuals, genders, and cultures. In Mexico, when doing business, men may find themselves being grasped on the arm by another man. To pull away is seen as rude. In Indonesia, to touch anyone on the head or to touch anything with one’s foot is considered highly offensive. In the Far East and some parts of Asia, according to business etiquette writer Nazir Daud, “It is considered impolite for a woman to shake a man’s hand” (Daud, 2008). Americans, as we have noted above, place great value in a firm handshake. But handshaking as a competitive sport (“the bone-crusher”) can come off as needlessly aggressive both at home and abroad.

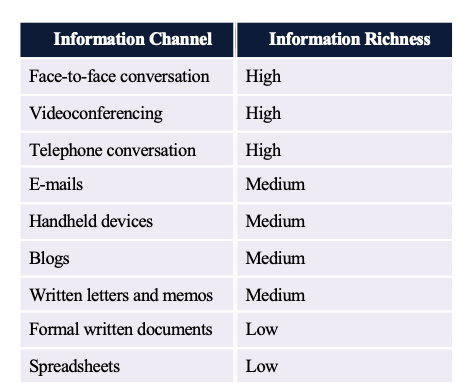

Communication Channels

The channel, or medium, used to communicate a message affects how accurately the message will be received. Channels vary in their “information-richness.” Information-rich channels convey more non-verbal information. Research shows that effective managers tend to use more information-rich communication channels than less effective managers (Allen & Griffeth, 1997; Yates & Orlikowski, 1992). The figure below illustrates the information richness of different channels.

The key to effective communication is to match the communication channel with the goal of the message (Barry & Fulmer, 2004). For example, written media may be a better choice when the sender wants a record of the content, has less urgency for a response, is physically separated from the receiver, and doesn’t require a lot of feedback from the receiver or when the message is complicated and may take some time to understand.

Oral communication, on the other hand, makes more sense when the sender is conveying a sensitive or emotional message, needs feedback immediately, and does not need a permanent record of the conversation.

Like face-to-face and telephone conversations, videoconferencing has high information richness, because receivers and senders can see or hear beyond just the words that are used—they can see the sender’s body language or hear the tone of their voice. Handheld devices, blogs, written letters, and memos offer medium-rich channels because they convey words and pictures or photos. Formal written documents, such as legal documents and budget spreadsheets, convey the least richness because the format is often rigid and standardized. As a result, the tone of the message is often lost.

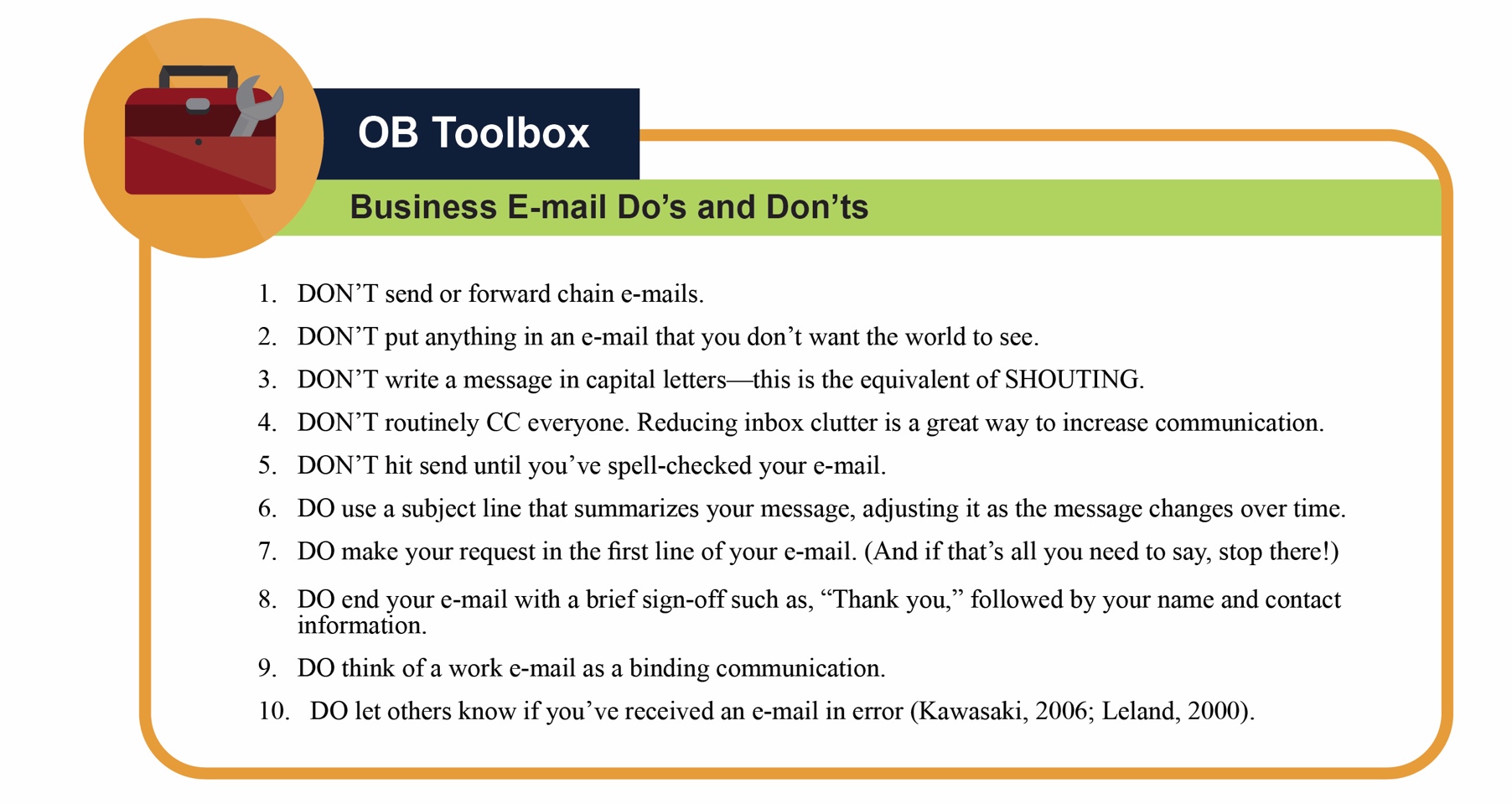

The growth of e-mail has been spectacular, but it has also created challenges in managing information and increasing the speed of doing business. Over 100 million adults in the United States use e-mail at least once a day (Taylor, 2002). Internet users around the world send an estimated 60 billion e-mails each day, and a large portion of these are spam or scam attempts (60 Billion emails sent daily worldwide, 2006). That makes e-mail the second most popular medium of communication worldwide, second only to voice. Less than 1% of all written human communications even reach paper these days (Isom, 2008). To combat the overuse of e-mail, companies such as Intel have even instituted “no e-mail Fridays.” During these times, all communication is done via other communication channels. Learning to be more effective in your e-mail communications is an important skill. To learn more, check out the OB Toolbox on business e-mail do’s and don’ts.

You might feel uncomfortable conveying an emotionally laden message verbally, especially when the message contains unwanted news. Sending an e-mail to your staff that there will be no bonuses this year may seem easier than breaking the bad news face-to-face, but that doesn’t mean that e-mail is an effective or appropriate way to break this kind of news. When the message is emotional, the sender should use verbal communication. Indeed, a good rule of thumb is that more emotionally laden messages require more thought in the choice of channel and how they are communicated.

Cross-Cultural Communication

Culture is a shared set of beliefs and experiences common to people in a specific setting. The setting that creates a culture can be geographic, religious, or professional. As you might guess, the same individual can be a member of many cultures, all of which may play a part in the interpretation of certain words.

The different and often “multicultural” identity of individuals in the same organization can lead to some unexpected and potentially large miscommunications. For example, during the Cold War, Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev told the American delegation at the United Nations, “We will bury you!” His words were interpreted as a threat of nuclear annihilation. However, a more accurate reading of Khruschev’s words would have been, “We will overtake you,” meaning economic superiority. The words, as well as the fear and suspicion that the West had of the Soviet Union at the time, led to a more alarmist and sinister interpretation (Garner, 2007).

Miscommunications can arise between individuals of the same culture as well. Many words in the English language mean different things to different people. Words can be misunderstood if the sender and receiver do not share common experiences. A sender’s words cannot communicate the desired meaning if the receiver has not had some experience with the objects or concepts the words describe (Effective communication, 2004).

It is particularly important to keep this fact in mind when you are communicating with individuals who may not speak English as a first language. For example, when speaking with non-native English-speaking colleagues, avoid “isn’t it?” questions. This sentence construction does not exist in many other languages and can be confusing for non-native English speakers. For example, to the question, “You are coming, aren’t you?” they may answer, “Yes” (I am coming) or “No” (I am coming), depending on how they interpret the question (Lifland, 2006).

Cultures also vary in terms of the desired amount of situational context related to interpreting situations. People in very high-context cultures put a high value on establishing relationships before working with others and tend to take longer to negotiate deals. Examples of high-context cultures include China, Korea, and Japan. Conversely, people in low-context cultures “get down to business” and tend to negotiate quickly. Examples of low-context cultures include Germany, Scandinavia, and the United States (Hall, 1976; Munter, 1993).

Finally, don’t forget the role of nonverbal communication. As we learned in the nonverbal communication section, in the United States, looking someone in the eye when talking is considered a sign of trustworthiness. In China, by contrast, a lack of eye contact conveys respect. A recruiting agency that places English teachers warns prospective teachers that something that works well in one culture can offend in another: “In Western countries, one expects to maintain eye contact when we talk with people. This is a norm we consider basic and essential. This is not the case among the Chinese. On the contrary, because of the more authoritarian nature of the Chinese society, steady eye contact is viewed as inappropriate, especially when subordinates talk with their superiors” (Chinese culture-differences and taboos).

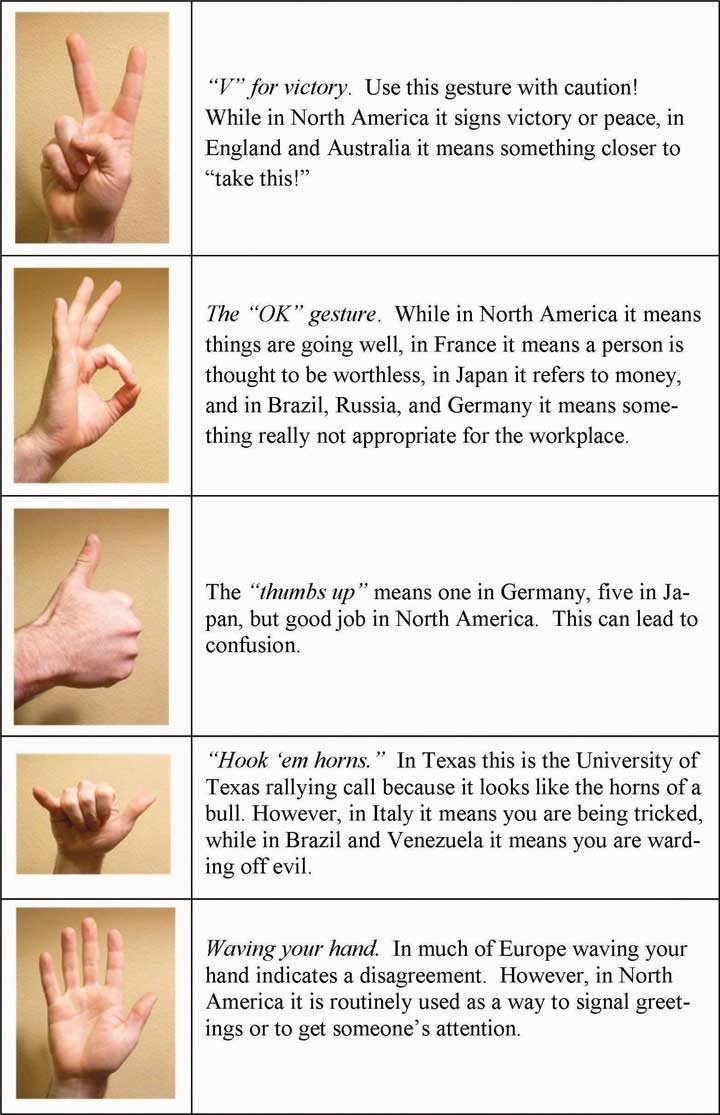

It’s easy to see how meaning could become confused, depending on how and when these signals are used. When in doubt, experts recommend that you ask someone around you to help you interpret the meaning of different gestures, that you be sensitive, and that you remain observant when dealing with a culture different from your own.

8.5 Employee Satisfaction Translates to Success: The Case of Edward Jones

Because of the economic turmoil that most financial institutions find themselves in today, it might come as a surprise that an individual investment company came in at number 2 on Fortune magazine’s “100 Best Companies to Work For” list in 2010, behind software giant SAS Institute Inc. Edward Jones Investments (a limited partnership company) was originally founded in St. Louis, Missouri, where its headquarters remain today. With more than 10,000 offices across the United States and Canada, they can serve nearly 7 million investors. This is the 10th year Edward Jones has made the Best Companies list. In addition, Edward Jones ranked highest in client satisfaction among full-service investment firms, according to an annual survey released by J. D. Power and Associates in 2009. How has Edward Jones maintained this favorable reputation in the eyes of both its employees and customers?

It begins with the perks offered, including profit sharing and telecommuting. But if you ask the company’s CEO, Tim Kirley, he will likely tell you that it goes beyond the financial incentives, and at the heart of it is the culture of honest communication that he adamantly promotes. Kirley works with senior managers and team members in what makes up an open floor plan and always tries to maintain his approachability. Examples of this include direct communication, letters to staff and videos, and Internet-posted talks. In addition, regular meetings are held to celebrate achievements and reinforce the firm’s ethos. Staff surveys are frequently administered, and feedback is widely taken into consideration so that the 10,000 employees feel heard and respected.

According to Fortune’s managing editor, Hank Gilman, “The most important considerations for this year’s list were hiring and how companies are helping their employees weather the recession.” Edward Jones was able to persevere through the trauma of the recent financial crisis with no layoffs and an 8% one-year job growth. While a salary freeze was enacted, profit sharing continued. Kirley insists that the best approach to the recent economic downturn is to remain honest with his employees even when the news he is delivering is not what they want to hear.

Edward Jones was established in 1922 by Edward D. Jones Sr., and long ago, the company recognized the importance of a satisfied workforce and how that can translate into customer satisfaction and long-term growth. The company’s internal policy of open communication seems to carry over to how advisors value their relationship with individual customers. Investors are most likely to contact their advisors by directly visiting them at a local branch or by picking up the phone and calling them. Edward Jones’s managing partner, Jim Weddle, explains it best himself: “We can stay focused on the long-term because we are a partnership, and we know who we are and what we do. When you respect the people who work here, you take care of them—not just in the good times, but in the difficult times as well” (100 best companies to work for, 2010; Keeping clients happy, 2009; Lawlor, 2008; Rodrigues & Clayton, 2009; St. Louis firms make Fortune’s best workplaces, 2009).

Communication in a Virtual Work Environment With New Technologies

Covid-19 has revolutionized the way we work and communicate with others while working. Remote work has had a significant impact on workplace communication, both positively and negatively, in some of the following ways:

- Increase in digital communication: With remote work, there has been a significant increase in the use of digital communication tools such as email, instant messaging, video conferencing, and project management software. These tools allow employees to communicate and collaborate effectively regardless of their location.

- Flexibility: Remote work has also allowed for greater flexibility in communication. Employees can choose the communication tools that work best for them, and they can communicate at times that are most convenient for them.

- Lack of nonverbal cues: One of the challenges of remote work is the lack of nonverbal cues. When communicating digitally, it can be challenging to pick up on facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice. This can lead to misinterpretation and misunderstandings.

- The increased importance of written communication skills: With the rise in digital communication, written communication skills have become more critical than ever. Employees need to be able to write clearly and effectively to avoid misunderstandings and confusion.

- Need for intentional communication: With remote work, communication needs to be intentional. Managers need to be more deliberate in communicating with their team members, and employees need to be more intentional in seeking out communication when they need it.

- More Asynchronous Communication: Remote work has allowed for more asynchronous communication, where people can communicate with each other at different times. For example, someone can send an email or a message outside of work hours, and the recipient can respond later.

- Increased Importance of Clear Communication: With remote work, there is a greater need for clear communication. Misunderstandings can arise more easily when people are not face-to-face, so it’s important to be clear in our writing and make sure we understand each other.

- Increased Use of Video Conferencing: Video conferencing has become more popular as remote work has become more common. This allows people to have face-to-face interactions without being in the same room, which can help build better relationships among colleagues.

Overall, remote work has had a significant impact on workplace communication. While there are some challenges, there are also many benefits to remote communication, such as increased flexibility and access to digital tools.

Not only has remote work significantly changed the way we communicate, but the increased adoption of new technologies such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, SharePoint, and even Ai Software such as Chat GPT has revolutionized how we communicate. It may be of interest to note that the above list of ways in which remote work has changed our communication at work was generated by Chat GPT! https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt

The adoption of Ai technology exploded in 2022, with the release of platforms such as Chat GPT changing the world of communication forever. Funk (2023) explains the benefits and challenges of Ai technology as follows (p2):

The Benefits of AI in Communication

Ability to improve accessibility and efficiency. For example, chatbots and virtual assistants can provide instant responses to inquiries and customer service requests, freeing up human customer service agents to focus on more complex tasks. AI-powered translation services can also break down language barriers and facilitate communication between individuals who speak different languages.

Enhance the personalization of communication. With access to large amounts of data, AI-powered tools can analyze user behavior and preferences, tailoring communication to suit the individual’s needs. Additionally, AI can use predictive capabilities to anticipate what a user may need or want, providing suggestions and recommendations that can enhance the user’s experience. For example, Spotify uses AI to curate personalized playlists for its users, based on their listening history and preferences.

Ability to analyze and interpret large amounts of data. This provides insights that can help individuals and organizations make more informed decisions. For example, social media monitoring tools can use AI to analyze trends and sentiment across social media platforms, helping businesses to better understand their audience and improve their marketing strategies.

The Challenges and Risks of AI in Communication

Difficultly to differentiate between AI-generated and human-generated communication. For example, as AI becomes more sophisticated, it may be more difficult to differentiate between text written by a computer versus a human. This could lead to issues with trust and transparency, particularly in areas such as journalism and marketing.

Increased Bias. AI algorithms may perpetuate biases and reinforce existing inequalities if they are not properly designed and tested. Research has shown that AI language models can perpetuate gender and racial biases, reflecting the biases that are present in the data they are trained on. For example, a study by the AI Now Institute found that popular language models such as GPT-2, 3, 4 and BERT have gender biases, with male pronouns and names being more frequently associated with career-related words than female pronouns and names.

Communication Among Neurodiverse Individuals

An increasing amount of research is being conducted examining the role of communication among neurodiverse individuals. To encourage sustainable growth, many bet performing companies are looking to identify new talent and have found that neurodiverse individuals — those with autism, Asperger’s syndrome, dyslexia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and dyspraxia — can create innovation and contribute to the skills needed for emerging areas such as artificial intelligence, automation, blockchain, cybersecurity and data management (Twaronite, 2020). Over 15% of the Canadian workforce is neurodiverse, and leveraging the unique capabilities of these employees is becoming a competitive advantage among organizations (Bitti, 2022). Leveraging the unique talents of neurodiverse individuals involves having an environment that encourages open and clear communication for all team members to connect with leaders, colleagues, and each other. Specifically, Twaronite (2020) recommends that workplaces:

- Communicate using straightforward language. Neurodiverse employees are more often likely to takecommunication at face value. Therefore, avoiding sarcasm and expressions that may be misunderstood or misinterpreted can go a long way. Neurodiverse colleagues will understand you more easily if you state youremotions and ask specific questions rather than open-ended ones.

- Embrace honesty. Individuals on the autism spectrum typically speak with complete honesty, and their frankness can sometimes be incorrectly mistaken for rudeness. It’s important to reflect and understand thatthese comments often stem from individuals coping with the stress of sensory overload. Finding ways to workwith and embrace different communication styles can help make certain everyone feels like they have a voice at the table.

- Pace the flow of information. Our neurodiverse colleagues have made invaluable contributions to ourorganization because of their technologically inclined and detail-oriented abilities, along with their strongskills in analytics, mathematics, pattern recognition, and information processes. However, when others communicate facts, data, and other information, it should be done so in a logical and ordered sequence toavoid information overload. Also, remember the power of the pause — allow for rest and recovery time inbetween sharing information — to give your team members more time to process what has been said.

- Be mindful of sensitivities. At times, individuals on the spectrum may be disconcerted by sounds, sights, andmovement. Changes in routine or personnel, such as having to work remotely abruptly, can take some timefor neurodiverse individuals to adjust. When communicating about changes, be patient and allow extra timefor them to adapt. (p.2)

8.6 Conclusion

In this chapter, we have reviewed why effective communication matters to organizations. Communication may break down as a result of many communication barriers that may be attributed to the sender or receiver. Therefore, effective communication requires familiarity with the barriers. Choosing the right channel for communication is also important because choosing the wrong medium undermines the message. When communication occurs in a cross-cultural context, extra caution is needed, given that different cultures have different norms regarding nonverbal communication, and different words will be interpreted differently across cultures. By being sensitive to the errors outlined in this chapter and adopting active listening skills, you may increase your communication effectiveness.