Chapter 7: Managing Stress and Emotions

Chapter Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you should be able to know and learn the following:

- Understand the stress cycle.

- Recognize the sources of stress for employees.

- Recognize the outcomes of stress.

- Understand how to manage stress in organizational contexts.

- Learn about emotional labour and how to manage it.

- Learn about emotional intelliegence and how to lead with it.

Introduction

The effects of stress and mental health in a post pandemic world

The debilitating effects of the Covid-19 pandemic—economic, governmental, and personal—are finally beginning to fade around the world and yet caution is till advised.

The virus still poses serious threats to public health, however, and interventions to disrupt its spread, such as quarantine and social distancing, will be required to keep the virus in check for the foreseeable future. Stress and anxiety tied to the coronavirus, coupled with the various institutional countermeasures, have exerted significant negative effects on the mental health of people worldwide. Numerous studies, including one conducted by researchers at Columbia University, found the global prevalence of depression and anxiety almost doubled from 2020 to 2021. According to researchers at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, three groups—women, young people, and persons of low socioeconomic status—are especially vulnerable to covid-related psychological trauma.

Even today, some people experience stress and anxiety, characterized by feelings of nervousness, worry, or unease. People remain concerned about becoming infected, the health and safety of loved ones, economic disruptions, instability in family routines, and other disruptions to daily life. People may feel overwhelmed and unable to deal with day-to-day activities when stress and anxiety are extremely intense or persistent. Mental distress can also weaken the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to the coronavirus and all manner of physical illness.

Fortunately, a return to normalcy seems to be finally upon us. Seneca College welcomed back students over the summer of 2022, reopening the main campus. While a departure from mandated quarantine is welcomed by most—allowing people to return to work or study, engage in outside activities, and socialize—it can also be a source of concern or dread. Post-quarantine anxiety may occur, for example, when one finds themselves surrounded by large crowds of people after such a prolonged period of limited social exposure. While returning to normalcy can be challenging, it is an important step toward the restoration of one’s mental health. Not to say such changes are easy. A 2021 survey by the American Psychological Association found nearly half of all survey respondents (49%) felt anxious about a return to person-to-person interactions.

Stress, especially chronic or prolonged stress, can have profound effects on the body. Stress is known to activate the so-called HPA axis, involving the Hypothalamus, Pituitary gland, and Adrenal glands. The end result is the release of adrenaline and a stress hormone called cortisol. Prolonged elevations in cortisol, due to chronic stress, exerts deleterious effects on the gastrointestinal system and many other parts of the body. Cortisol, for example, drives an elevation in both heart rate and blood pressure—preparing individuals for fight-or-flight—which is tied to a variety of cardiovascular issues. As such, long-term stress can increase an individual’s risk for hypertension, heart attack, or stroke. A less severe, but no less disruptive consequence of chronic stress involves muscle tension—imagine someone gritting their teeth. Musculoskeletal pain is also associated with both tension- and migraine headaches which can be highly disruptive in a person’s day-to-day living.

There is no single approach for dealing with stress and anxiety. However, a proactive approach to self-care and mindfulness will go a long way toward healing and repairing the physical and psychological toll of covid-19. It is important, when possible, to not do it alone—mental health is a collective responsibility and requires sustained efforts by individuals, families, and communities. To that end, it is well established that the use of appropriate precautionary behaviour, including face masks and social distancing, can ease one’s anxiety, allowing individuals to feel more confident in their ability to effectively manage social interactions.

Maintaining, or re-establishing, social connections with family, friends, and colleagues—whether online or in person—can help ease social anxiety. Relaxation techniques such as meditation or deep breathing exercises have also been shown to effectively reduce muscle tension and increase one’s psychological well-being. Alterations in sleep, including insomnia, are common symptoms of anxiety. It is imperative, therefore, to maintain a normal sleep-wake cycle and attain proper rest each night. It is also vital to stay physically active and exercise—maintaining a healthy body is one of the best ways to sustain a healthy mind. Finally, excessive consumption of licit or illicit substances, such as alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, or narcotics, should be avoided. Such substances may provide short-term stress relief, but they typically prolong and exacerbate anxiety in the long run.

7.1 What Is Stress?

Gravity. Mass. Magnetism. These words come from the physical sciences. So does the term stress. In its original form, the word stress relates to the amount of force applied to a given area. A steel bar stacked with bricks is being stressed in ways that can be measured using mathematical formulas. In human terms, psychiatrist Peter Panzarino notes, “Stress is simply a fact of nature—forces from the outside world affecting the individual” (Panzarino, 2008). The professional, personal, and environmental pressures of modern life exert their forces on us every day. Some of these pressures are good. Others can wear us down over time.

Stress is defined by psychologists as the body’s reaction to a change that requires a physical, mental, or emotional adjustment or response (Dyer, 2006). Stress is an inevitable feature of life. It is the force that gets us out of bed in the morning, motivates us at the gym, and inspires us to work.

We may not be able to avoid stress completely, but we can change how we respond to stress, which is a major benefit. Our ability to recognize, manage, and maximize our response to stress can turn an emotional or physical problem into a resource.

A new report released in May 2022, by Lifeworks’ (a human resources services and technology company headquartered in Toronto, Canada) has found that 46 per cent of Canadians are feeling an increased sensitivity to stress than they were prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, impacting their overall mental health.

According to the report many Canadians are expressing more “stress sensitivity concerns” about themselves and their colleagues compared to pre-pandemic levels.

The report found that 49 per cent of working Canadians say they have noticed their colleagues are more sensitive to stress, with 46 per cent indicating the same for themselves. Of those surveyed, 22 per cent said they were unsure.

In addition, 45 per cent of employed Canadians said the pandemic has had a negative impact on their ongoing mental health.

LifeWorks President and CEO Stephen Liptrap said stressors inside and outside of the workplace continue to make it challenging for Canadians to manage their mental well-being “in a healthy way.”

“It is important for employers to recognize there is often more than meets the eye when it comes to how employees are feeling, and that providing ongoing communication and support is critical to ensure employee mental health remains a top priority,” Liptrap said.

Workplace Stressors

Stressors are events or contexts that cause a stress reaction by elevating levels of adrenaline and forcing a physical or mental response. The key to remember about stressors is that they aren’t necessarily a bad thing. The saying “the straw that broke the camel’s back” applies to stressors. (“the straw that broke the camel’s back” – meaning – the last in a series of bad things that happen to make someone very upset, angry, etc. Example: It had been a difficult week, so when the car broke down, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back).

Having a few stressors in our lives may not be a problem, but because stress is cumulative, having many stressors day after day can cause a buildup that becomes a problem. The American Psychological Association surveys American adults about their stresses annually. Topping the list of stressful issues are money, work, and housing (American Psychological Association, 2007). But in essence, we could say that all three issues come back to the workplace. How much we earn determines the kind of housing we can afford, and when job security is questionable, home life is generally affected as well.

Understanding what can potentially cause stress can help avoid negative consequences. Now we will examine the major stressors in the workplace.

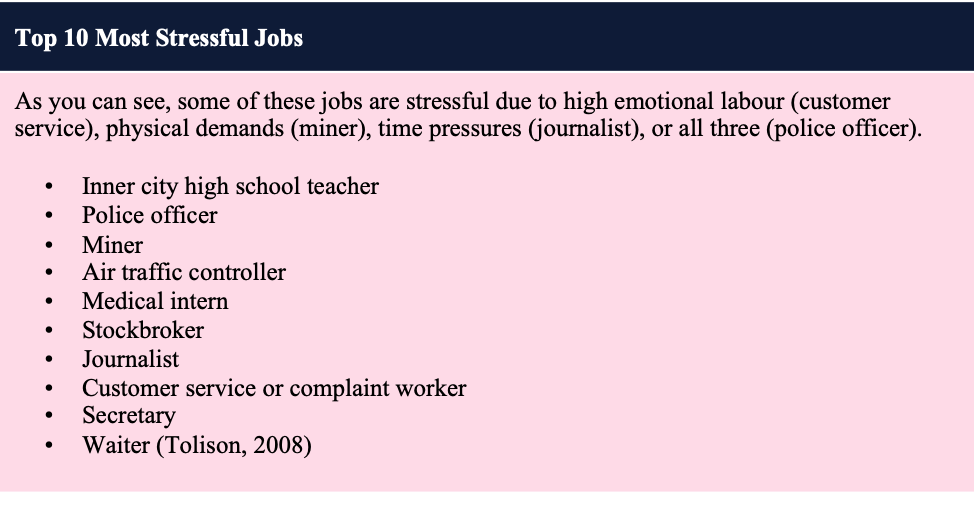

A major category of workplace stressors are role demands. In other words, some jobs and some work contexts are more potentially stressful than others.

Role Demands

Role ambiguity refers to vagueness in what our responsibilities are. If you started a new job and felt unclear about what you were expected to do, you have experienced role ambiguity. Having high role ambiguity is related to higher emotional exhaustion, more thoughts of leaving an organization, and lowered job attitudes and performance (Fisher & Gittelson, 1983; Jackson & Shuler, 1985; Örtqvist & Wincent, 2006).

Role conflict refers to facing contradictory demands at work. For example, your manager may want you to increase customer satisfaction and cut costs, while you feel that satisfying customers inevitably increases costs. In this case, you are experiencing role conflict because satisfying one demand makes it unlikely to satisfy the other.

Role overload is defined as having insufficient time and resources to complete a job. When an organization downsizes, the remaining employees will have to complete the tasks that were previously performed by the laid-off workers, which often leads to role overload. Like role ambiguity, both role conflict and role overload have been shown to hurt performance and lower job attitudes; however, research shows that role ambiguity is the strongest predictor of poor performance (Gilboa et al., 2008; Tubre & Collins, 2000). Research on new employees also shows that role ambiguity is a key aspect of their adjustment, and that when role ambiguity is high, new employees struggle to fit into the new organization (Bauer et al., 2007).

Information Overload

Have you started a Google search for something of interest and then suddenly realised that you have spend more than an hour on the web reading and viewing more than you had intended. And along that process you were bombarded with embedded videos that slowed down your speed of reading what you wanted to. According to marketing experts, the average person sees between 4,000 and 10,000 ads in a single day.

The gigantic mountain of information is at the root of the problem of information stress. Because we all have access to the internet, smartphones and social media, all information is always available. E-mails, apps, photos, videos and text messages. On and in Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, news media, apps, websites and business presentations… This is only a fraction of all the information we take in. Or – more accurately – that is fired at us.

Add these together and it’s easy to see how we may be receiving more information than we can take in. This state of imbalance is known as information overload, which can be defined as “occurring when the information processing demands on an individual’s time to perform interactions and internal calculations exceed the supply or capacity of time available for such processing” (Schick, Gordon, & Haka, 1990).

Many people suffer from information overload. Thanks to information, we can communicate quickly and extensively with others, we know what colleagues are doing and we know what is happening in the world. But for many people, it leaves a sour taste in the mouth. The overwhelming amount of information blurs the line between valuable information and distraction and makes it harder for them to keep track of and filter information. The result is information overload.

Psychologists report that information stress can exhaust and demoralise us, resulting in symptoms similar to attention deficit disorder (ADD). Ultimately, this can lead to overwork, burn-out or depression. It is one of the causes of the alarming increase in burn-outs in recent years: as many as one in ten Europeans, for example, have feelings resembling a burn-out.

The impact on productivity

Information overload related stress has a detrimental effect on productivity. After all, employees who are distracted by currently irrelevant information cannot spend their time doing useful work. Moreover, it takes a lot of time and cognitive energy to get back to the work we were doing before we were distracted by a notification or a new message.

Employees could take as long as 24 minutes before they are fully focused on the task they were doing before opening an email. This is because they also read other emails or send messages to friends, but also because they spend time scrolling through open applications to find out what they were doing again and get distracted by it again. Seeing an unread email while completing a task is said to lower your effective IQ by up to ten points. Even young people – who have grown up in a jungle of online distractions – appear to need uninterrupted periods of time in order to complete challenging tasks effectively.

Work–Family Conflict

Work–Family Conflict

We all play many roles: employee, manager, spouse, parent, child, sibling, friend, and community member. Each of these roles imposes demands on us that require time, energy and commitment to fulfill. Work-family or work-life conflict occurs when the cumulative demands of these many work and non-work roles are incompatible in some respect, so that participation in one role is made more difficult by participation in the other role

Specifically, work and family demands on a person may be incompatible with each other such that work interferes with family life and family demands interfere with work life. This stressor has steadily increased in prevalence, as work has become more demanding, and technology has allowed employees to work from home and be connected to the job around the clock.

The key findings from The 2001 National Work-Life Conflict Study were that Canadians identified the following factors of work-family-life conflict:

• Heavy workloads

• Cultures that do not support balance

• The perception that one has to choose between career advancement and balance

• Constant change

• Management that does not support balance

• Lack of policies

• Temporary work

• Work-related travel

Moreover, the fact that more households have dual-earning families in which both adults work means household and childcare duties are no longer the sole responsibility of a stay-at-home parent. This trend only compounds stress from the workplace by leading to the spillover of family responsibilities (such as a sick child or elderly parent) to work life. Research shows that individuals who have stress in one area of their life tend to have greater stress in other parts of their lives, which can create a situation of escalating stressors (Allen et al., 2000; Ford, Heinen, & Langkamer, 2007; Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1992; Hammer, Bauer, & Grandey, 2003).

Work–family conflict has been shown to be related to lower job and life satisfaction. Interestingly, it seems that work–family conflict is slightly more problematic for women than men (Kossek & Ozeki, 1998). Organizations that are able to help their employees achieve greater work–life balance are seen as more attractive than those that do not (Barnett & Hall, 2001; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Organizations can help employees maintain work–life balance by using organizational practices such as flexibility in scheduling as well as individual practices such as having supervisors who are supportive and considerate of employees’ family life (Thomas & Ganster, 1995).

Life Changes

Stress can result from positive and negative life changes. The Holmes-Rahe scale ascribes different stress values to life events ranging from the death of one’s spouse to receiving a ticket for a minor traffic violation. The values are based on incidences of illness and death in the 12 months after each event. On the Holmes-Rahe scale, the death of a spouse receives a stress rating of 100, getting married is seen as a midway stressful event, with a rating of 50, and losing one’s job is rated as 47. These numbers are relative values that allow us to understand the impact of different life events on our stress levels and their ability to impact our health and well-being (Fontana, 1989). Again, because stressors are cumulative, higher scores on the stress inventory mean you are more prone to suffering negative consequences of stress than someone with a lower score.

Outcomes of Stress

The outcomes of stress are categorized into physiological, psychological, and work outcomes.

Physiological

Stress manifests itself internally as nervousness, tension, headaches, anger, irritability, and fatigue. Stress can also have outward manifestations. Dr. Dean Ornish, author of Stress, Diet and Your Heart, says that stress is related to aging (Ornish, 1984). Chronic stress causes the body to secrete hormones such as cortisol, which tend to make our complexion blemished and cause wrinkles. Harvard psychologist Ted Grossbart, author of Skin Deep, says, “Tens of millions of Americans suffer from skin diseases that flare up only when they’re upset” (Grossbart, 1992). These skin problems include itching, profuse sweating, warts, hives, acne, and psoriasis. For example, Roger Smith, the former CEO of General Motors Corporation, was featured in a Fortune article that began, “His normally ruddy face is covered with a red rash, a painless but disfiguring problem which Smith says his doctor attributes 99% to stress” (Taylor, 1987).

The human body responds to outside calls to action by pumping more blood through our system, breathing in a shallower fashion, and gazing wide-eyed at the world. To accomplish this feat, our bodies shut down our immune systems. From a biological point of view, it’s a smart strategic move—but only in the short term. The idea can be seen as your body wanting to escape an imminent threat, so that there is still some kind of body around to get sick later. But in the long term, a body under constant stress can suppress its immune system too much, leading to health problems such as high blood pressure, ulcers, and being overly susceptible to illnesses such as the common cold.

Psychological

Depression and anxiety are two psychological outcomes of unchecked stress, which are as dangerous to our mental health and welfare as heart disease, high blood pressure, and strokes. The Harris poll found that 11% of respondents said their stress was accompanied by a sense of depression. “Persistent or chronic stress has the potential to put vulnerable individuals at a substantially increased risk of depression, anxiety, and many other emotional difficulties,” notes Mayo Clinic psychiatrist Daniel Hall-Flavin. Scientists have noted that changes in brain function—especially in the areas of the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland—may play a key role in stress-induced emotional problems (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2008).

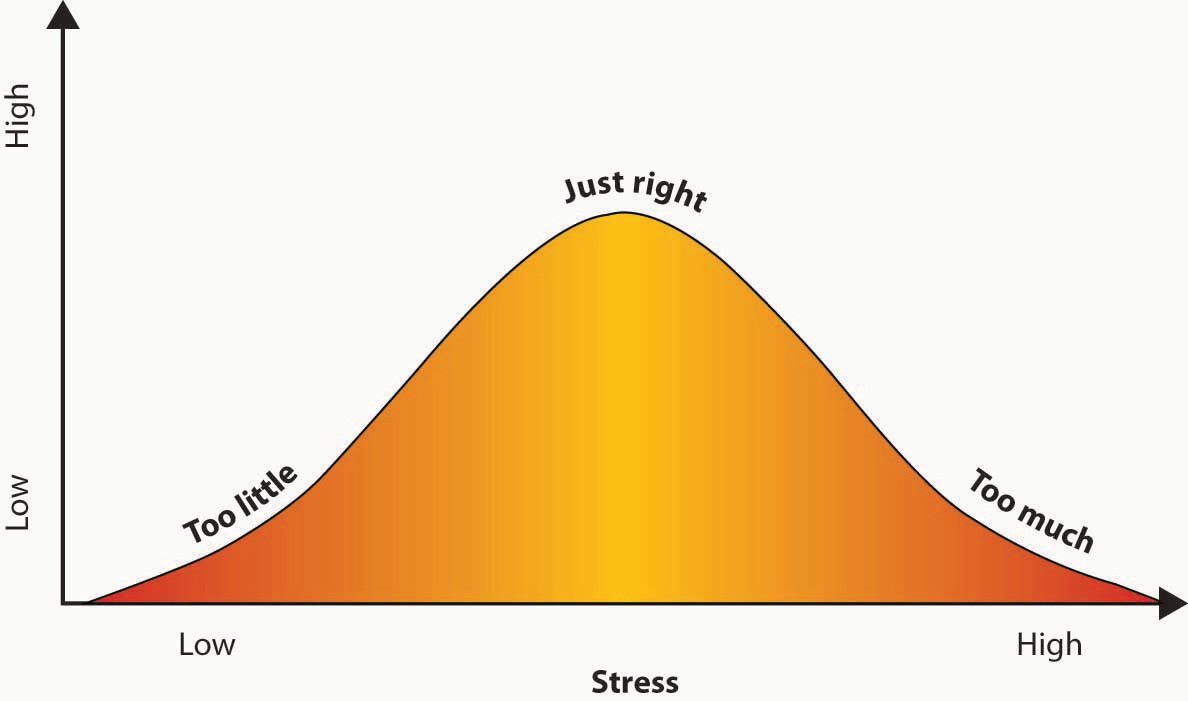

Work Outcomes

Stress is related to worse job attitudes, higher turnover, and decreases in job performance in terms of both in-role performance and organizational citizenship behaviours (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2008; Gilboa et al., 2008; Podsakoff et al., 2007). Research also shows that stressed individuals have lower organizational commitment than those who are less stressed (Cropanzano, Rupp, & Byrne, 2003). Interestingly, job challenge has been found to be related to higher performance, perhaps with some individuals rising to the challenge (Podsakoff et al., 2007). The key is to keep challenges in the optimal zone for stress—the activation stage—and to avoid the exhaustion stage (Quick et al., 1997).

Individual Differences in Experienced Stress

How we handle stress varies by individual, and part of that issue has to do with our personality type.

Type A personalities, as defined by the Jenkins Activity Survey (Jenkins, Zyzanski, & Rosenman, 1979), display high levels of speed/impatience, job involvement, and hard-driving competitiveness. Unchecked stress can lead to illness over time. It is easy to see how the fast-paced, adrenaline-pumping lifestyle of a Type A person can lead to increased stress, and research supports this view (Spector & O’Connell, 1994). Studies show that the hostility and hyper-reactive portion of the Type A personality is a major concern in terms of stress and negative organizational outcomes (Ganster, 1986).

Type B personalities, by contrast, are calmer by nature. They think through situations as opposed to reacting emotionally. Their fight-or-flight and stress levels are lower as a result. Our personalities are the outcome of our life experiences and, to some degree, our genetics. Some researchers believe that mothers who experience a great deal of stress during pregnancy introduce their unborn babies to high levels of the stress-related hormone cortisol in utero, predisposing their babies to a stressful life from birth (BBC News, 2007).

Men and women also handle stress differently. Researchers at Yale University discovered estrogen may heighten women’s response to stress and their tendency to depression as a result (Weaver, 2004). Still, others believe that women’s stronger social networks allow them to process stress more effectively than men (Personality, n.d.). So while women may become depressed more often than men, women may also have better tools for countering emotion-related stress than their male counterparts.

Work and academic acheivement

A 2019 study compared academic achievement between university students with type A and type B personalities.

Both personality types had characteristics that were both beneficial and detrimental to academic achievement.

Certain characteristics of type A personality, such as being hardworking and goal-orientated, increased academic achievement. Higher levels of hostility and impatience had a negative correlation to academic achievement.

Certain characteristics of a type B personality, such as being easygoing, having a lack of focus on study, and procrastination, linked to a decrease in academic achievement. Patience, taking tasks one by one, and sociability linked to an increase in academic achievement.

Overall, the study suggests students with type A personalities may achieve higher academic achievements.

Health

According to a 2017 study, people with a type A personality may be more at risk of stress and burnout than people with a type B personality.

This may be due to the different approaches people with type A or type B personalities take to deal with and manage stress.

People with type B personalities may be more adaptive and tolerant and more capable of managing stress, reducing the risk of stress-related health issues.

A 2019 study looked at the effects that mental and physical stress had on the heart in people with type A and B personality types.

The study concluded that mental stress may be harmful to both personality types, whereas physical stress may be beneficial to people with type A personalities.

In summary, people with these personality traits may want to develop coping strategies to allow them to manage stress in a healthy way to help prevent stress-related health issues.

Are you a Type A or Type B personality. Do this personality test and know.

7.2 Avoiding and Managing Stress

Individual Approaches to Managing Stress

The Corporate Athlete

Luckily, there are several ways to manage stress. One way is to harness stress’s ability to improve our performance. Jack Groppel was working as a professor of kinesiology and bioengineering at the University of Illinois when he became interested in applying the principles of athletic performance to workplace performance. Could eating better, exercising more, and developing a positive attitude turn distress into eustress? Groppel’s answer was yes. If professionals trained their minds and bodies to perform at peak levels through better nutrition, focused training, and positive action, Groppel said, they could become “corporate athletes” working at optimal physical, emotional, and mental levels.

The “corporate athlete” approach to stress is a proactive (action first) rather than a reactive (response- driven) approach. While an overdose of stress can cause some individuals to stop exercising, eat less nutritional foods, and develop a sense of hopelessness, corporate athletes ward off the potentially overwhelming feelings of stress by developing strong bodies and minds that embrace challenges, as opposed to being overwhelmed by them.

Flow

Turning stress into fuel for corporate athleticism is one way of transforming a potential enemy into a workplace ally. Another way to transform stress is by breaking challenges into smaller parts and embracing the ones that give us joy. In doing so, we can enter a state much like that of a child at play, fully focused on the task at hand, losing track of everything except our genuine connection to the challenge before us. This concept of total engagement in one’s work, or in other activities, is called flow.

The term flow was coined by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and is defined as a state of consciousness in which a person is totally absorbed in an activity. We’ve all experienced flow: It’s the state of mind in which you feel strong, alert, and in effortless control.

Work that flows includes the following:

Next, let us focus more on exactly how individual lifestyle choices affect our stress levels. Eating well, exercising, getting enough sleep, and employing time management techniques are all things we can affect that can decrease our feelings of stress.

Diet

Greasy foods often make a person feel tired. Why? Because it takes the body longer to digest fats, which means the body is diverting blood from the brain and making you feel sluggish. Eating big, heavy meals in the middle of the day may slow us down, because the body will be pumping blood to the stomach, away from the brain. A better choice for lunch might be fish, such as wild salmon. Fish keeps you alert because of its effect on two important brain chemicals—dopamine and norepinephrine—which produce a feeling of alertness, increased concentration, and faster reaction times (Wurtman, 1988).

Exercise

Exercise is another strategy for managing stress. The best kind of break to take may be a physically active one. Research has shown that physically active breaks lead to enhanced mental concentration and decreased mental fatigue. One study, conducted by Belgian researchers, examined the effect of breaks on workers in a large manufacturing company. One-half of the workers were told to rest during their breaks. The other half did mild calisthenics. Afterward, each group was given a battery of tests. The group who had done the mild calisthenics scored far better on all measures of memory, decision-making ability, hand-eye coordination, and fine motor control (Miller, 1986).

Strange as it may seem, exercise gives us more energy. How energetic we feel depends on our maximum oxygen capacity (the total amount of oxygen we utilize from the air we breathe). The more oxygen we absorb in each breath, the more energy and stamina we will have. Yoga and meditation are other physical activities that are helpful in managing stress. Regular exercise increases our body’s ability to draw more oxygen out of the air we breathe. Therefore, taking physically active breaks may be helpful in combating stress.

Sleep

” If we all slept enough? …our healthcare burden would plummet, we would have better mental health and fewer suicides, our business would be more productive, global economies would be healthier, our roads would be safer, and our children would be smarter…sleep is the very best health insurance policy you could wish for”. Dr Matthew Walker PhD.

Dr. Walker is the director of the Center for Human Sleep Science at the University of California, Berkeley. He points out that lack of sleep — defined as six hours or fewer — can have serious consequences. Sleep deficiency is associated with problems in concentration, memory and the immune system, and may even shorten life span. “Human beings are the only species that deliberately deprive themselves of sleep for no apparent gain,” Walker says. “Many people walk through their lives in an under slept state, not realizing it.”

You can listen to Dr. Walker speak on the power of sleep :c8eee8c1-c87e-4ddf-9cf3-35d957978009 (1)

It is a vicious cycle. Stress can make it hard to sleep. Not sleeping makes it harder to focus on work in general, as well as on specific tasks. Tired folks are more likely to lose their temper, upping the stress level of others. American insomnia is a stress-related epidemic—one-third of adults claim to have trouble sleeping and 37% admit to actually having fallen asleep while driving in the past year (Tumminello, 2007).

The Public Health Agency of Canada has the following recommendations and findings:

Current recommendations are:

Ages 18-64

7-9 Hours of sleep/night

Ages 65+

7-8 Hours of sleep/night

But

1 in 4 adults aged 18-34

1 in 3 adults aged 35-64

1 in 4 adults aged 65-79

are not getting enough sleep.

The work–life crunch experienced by many Americans makes a good night’s sleep seem out of reach. According to the journal Sleep, workers who suffer from insomnia are more likely to miss work due to exhaustion. These missed days ultimately cost employers thousands of dollars per person in missed productivity each year, which can total over $100 billion across all industries. As you might imagine, a person who misses work due to exhaustion will return to work to find an even more stressful workload. This cycle can easily increase the stress level of the team as well as the overtired individual.

For additional resources, go to the National Sleep Foundation website: http://www.nationalsleepfoundation.org.

Create a Social Support Network

Social support network refers to a network of people – friends, family, and peers – that we can turn to for emotional and practical support.

Whether you are facing a personal crisis and need immediate assistance, or you just want to spend time with people who care about you, these relationships play a critical role in how you function in your day-to-day life.

Social support refers to the psychological and material resources provided by a social network to help individuals cope with stress. Such social support may come in different forms, and might involve:

- Helping a person with various daily tasks when they are ill or offering financial assistance when they are in need

- Giving advice to a friend when they are facing a difficult situation

- Providing caring, empathy and concern for loved ones in need

A consistent finding is that those individuals who have a strong social support network are less stressed than those who do not (Halbesleben, 2006). Research finds that social support can buffer the effects of stress (Van Yperfen & Hagedoorn, 2003). Individuals can help build up social support by encouraging a team atmosphere in which coworkers support one another. Just being able to talk with and listen to others, either with coworkers at work or with friends and family at home, can help decrease stress levels.

Time Management

Time management is defined as the development of tools or techniques that help to make us more productive when we work. Effective time management is a major factor in reducing stress, because it decreases much of the pressure we feel. With information and role overload it is easy to fall into bad habits of simply reacting to unexpected situations.

Good time management is essential if you are to handle a heavy workload without excessive stress. Time management helps you to reduce long-term stress by giving you direction when you have too much work to do.

It puts you in control of where you are going and helps you to increase your productivity. By being efficient in your use of time, you should enjoy your current work more, and should find that you able to maximise the time outside work to relax and enjoy life.

Poor time management is a major cause of stress. I’m sure we have all had the feeling that there is too much to do and not enough time. We can start to feel panicky and anxious and lose focus. It’s important to note that you can have this feeling even if there’s hardly anything to do at all.

Symptoms of stress caused by poor time management:

- Irritability and mood swings

- Tiredness and fatigue

- Inability to focus or concentrate. Do you ever feel like you are just trying to get yourself through the day?

- Mental block, memory lapses and forgetfulness.

- Lack of, or loss of, sleep

- At worst, withdrawal and depression

Also, when you have failed to manage your time you may be unclear about what is important and end up working on the things that are put in front of you or reacting to demands made by others rather than doing the work that needs to be done.

Time management techniques include prioritizing, manageable organization, and keeping a schedule such as a paper or electronic organizing tool. Just like any new skill, developing time management takes conscious effort, but the gains might be worthwhile if your stress level is reduced.

Organizational Approaches to Managing Stress

The Great Resignation or the Great State of Discontent

When offices shuttered across the country in March 2020 and millions of workers submitted to mandatory stay-at-home orders, many employees were forced to work remotely. Overnight, organizations had to pivot to a virtual-first or virtual-only mode of operation.

In a matter of weeks, our kitchens and bedrooms became our offices and our study places. For some, the sudden shift meant more than bringing work into their home; it meant they wore the hats of professionals, schoolteachers, students and caregivers all at once. For others, the time they previously spent dining out, attending concerts with friends, or sweating it out at the gym was suddenly freed up. Our lives became unrecognizable, triggering a total re-evaluation of the role of work.

With people dying, workers losing their jobs en masse, and parents overextended and exhausted, stress took on new dimensions and work suddenly seemed less important.

The Great Resignation was an outcome of that situation. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, nearly four million Americans quit their jobs in July 2021 alone. The resignation rate at a point in time in the U.S. was more than 11 million jobs open. One recent study found that 95% of workers would consider a job change. Harvard Business Review noted that employees between the ages of 30 and 45 have had the greatest jump in resignation rates, with an average increase of more than 20% between 2020 and 2021. As Time Magazine put it, “the pandemic revealed just how much we hate our jobs.”

More than just a Great Resignation, this is a state of discontent.

What are the causes of discontent and stressors at work.?

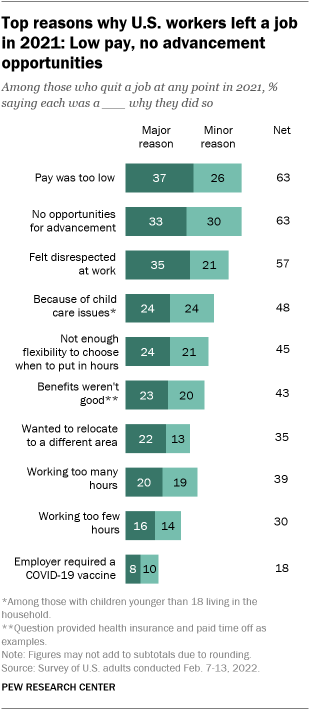

According to the Pew Research Centre, (see graphic below) besides dissatisfaction with pay and a lack of opportunities for advancement, the third most significant reason why workers in the United States left a job was ” Felt disrespected at work”

There are other factors that create dissatisfaction and stressful experiences at work :

- Poor workplace relationships – Job dissatisfaction might be caused by spending most of our time in an office environment, especially if that environment has inter-personal conflict that isn’t helping to fuel positivity.

- Denial of empowerment – Job satisfaction can often rest on how empowered an employee is made to feel within their role. They desire the opportunity to show their creativity or ingenuity and, if they’re denied this by a superior, it can often lead to job dissatisfaction, unhappiness and stress.

- Lack of work-life balance – Burnout caused by work overload is one of the major causes of employee dissatisfaction. Burnout can feel quite draining. Individuals who are burnt out from work might feel drained and tired most of the time. This may even be accompanied by physical symptoms – they may have back aches and headaches and may lose their appetite. Their sleep might be disrupted, and they may start to become reclusive and withdraw from others. They may have difficulty getting things done and may even feel like calling in sick to work more often than they should. Their confidence may be affected, and they may feel like a failure. This is in addition to feelings of helplessness – like there is no way out of their situation. Without a distinct line between work and home life, employees can quickly become overwhelmed and unable to switch off. Stress is a consequence of that state of being.

- Work isn’t meaningful – Repetitive work leads to boredom, to dissatisfaction and stress. This is typical of phone agents. Inbound customer service phone agents consistently have one of the highest turnover rates in the world. Agents deal with emotional customers, stress to perform, and often low pay.

- Felling unappreciated – Job satisfaction factors also include the amount of recognition and praise an employee receives from management. A recent study, by ADP, showed that two thirds of UK workers don’t feel valued, and many of them would consider leaving for a new opportunity because of this.

How can organizations reduce bad stress and develop sustainable long-term strategies for retention, employee satisfaction, and organizational growth, based on what is known about human desire, motivation, and job design?

Stress-related issues cost businesses billions of dollars per year in absenteeism, accidents, and lost productivity (Hobson, 2004). As a result, managing employee stress is an important concern for organizations as well as individuals. For example, Renault, the French automaker, invites consultants to train their 2,100 supervisors to avoid the outcomes of negative stress for themselves and their subordinates. IBM Corporation encourages its worldwide employees to take an online stress assessment that helps them create action plans based on their results. Even organizations such as General Electric Company (GE), known for their “winner takes all” mentality, are seeing the need to reduce stress. Lately, GE has brought in comedians to lighten up the workplace atmosphere, and those receiving low performance ratings are no longer called the “bottom 10s” but are now referred to as the “less effectives” (Dispatches from the war on stress, 2007).

Organizations can take many steps to helping employees with stress, including having more clear expectations of them, creating jobs where employees have autonomy and control, and creating a fair work environment. Finally, larger organizations normally utilize outside resources to help employees get professional help when needed.

Make Expectations Clear

One way to reduce stress is to state your expectations clearly. Workers who have clear descriptions of their jobs experience less stress than those whose jobs are ill defined (Jackson & Schuler, 1985; Sauter, Murphy, & Hurrell, 1990). The same thing goes for individual tasks. Can you imagine the benefits of working in a place where every assignment was clear and employees were content and focused on their work? It would be a great place to work as a manager, too. Stress can be contagious, but as we’ve seen above, this kind of happiness can be contagious too. Creating clear expectations doesn’t have to be a top–down event. Managers may be unaware that their directives are increasing their subordinates’ stress by upping their confusion. In this case, a gentle conversation that steers a project in a clearer direction can be a simple but powerful way to reduce stress. In the interest of reducing stress on all sides, it’s important to frame situations as opportunities for solutions as opposed to sources of anger.

Give Employees Autonomy

Giving employees a sense of autonomy is another thing that organizations can do to help relieve stress (Kossek, Lautschb, & Eaton, 2006). It has long been known that one of the most stressful things that individuals deal with is a lack of control over their environment. Research shows that individuals who feel a greater sense of control at work deal with stress more effectively both in the United States and in Hong Kong (Schaubroeck, Lam, & Xie, 2000). Similarly, in a study of American and French employees, researchers found that the negative effects of emotional labour were much less for those employees with the autonomy to customize their work environment and customer service encounters (Grandey, Fisk, & Steiner, 2005). Employees’ stress levels are likely to be related to the degree that organizations can build autonomy and support into jobs.

Create Fair Work Environments

Work environments that are unfair and unpredictable have been labelled “toxic workplaces.” A toxic workplace is one in which a company does not value its employees or treat them fairly (Webber, 1998). Statistically, organizations that value employees are more profitable than those that do not (Huselid, 1995; Pfeffer, 1998; Pfeffer & Veiga, 1999; Welbourne & Andrews, 1996). Research shows that working in an environment that is seen as fair helps to buffer the effects of stress (Judge & Colquitt, 2004). This reduced stress may be because employees feel a greater sense of status and self-esteem or due to a greater sense of trust within the organization. These findings hold for outcomes individuals receive as well as the process for distributing those outcomes (Greenberg, 2004). Whatever the case, it is clear that organizations have many reasons to create work environments characterized by fairness, including lower stress levels for employees. In fact, one study showed that training supervisors to be more interpersonally sensitive even helped nurses feel less stressed about a pay cut (Greenberg, 2006).

Telecommuting and Hybrid work

Telecommuting refers to working remotely. For example, some employees work from home, a remote satellite office, or from a coffee shop for some portion of the workweek. Being able to work away from the office is one option that can decrease stress for some employees.

A Qualtrics survey released in 2021 found that the ability to travel, move, and live away from an office — while still working their jobs — gave many a flexibility they don’t want to give up now that the pandemic is showing signs of abating.

- Over half of respondents (53%) said a long-term remote work policy would make them consider staying at their organization longer, and 10% said they would probably quit their job if they were forced back into the office full-time

- 80% of employees looking for a new job said it was important to them that their next job offer them the opportunity to live anywhere

- The younger generation seems to be more mobile: 25% of Gen Z and 17% of Millennials said they moved during the pandemic, compared to less than 10% of Gen X and Baby Boomers

Most don’t want to ditch the office completely, however. Many employees and leaders believe offices with a hybrid arrangement will outperform those without, especially as they cater to the individual needs of their employees.

The greatest advantages of hybrid work to date are : improved work-life balance, more efficient use of time, control over work hours and work location, burnout mitigation, and higher productivity. Hybrid work provides the flexibility for employees to work in ways that are most effective for them.

Employee Sabbaticals

Sabbaticals (paid time off from the normal routine at work) have long been a sacred ritual practiced by universities to help faculty stay current, work on large research projects, and recharge every 5 to 8 years. However, many companies such as Genentech Inc., Container Store Inc., and eBay Inc. are now in the practice of granting paid sabbaticals to their employees. While 11% of large companies offer paid sabbaticals and 29% offer unpaid sabbaticals, 16% of small companies and 21% of medium-sized companies do the same (Schwartz, 1999). For example, at PricewaterhouseCoopers International Ltd., you can apply for a sabbatical after just 2 years on the job if you agree to stay with the company for at least 1 year following your break. Time off ranges from 3 to 6 months and entails either a personal growth plan or one for social services where you help others (Sahadi, 2006).

Employee Assistance Programs

There are times when life outside work causes stress in ways that will impact our lives at work and beyond. These situations may include the death of a loved one, serious illness, drug and alcohol dependencies, depression, or legal or financial problems that are interfering with our work lives. Although treating such stressors is beyond the scope of an organization or a manager, many companies offer their employees outside sources for emotional counselling. Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) are often offered to workers as an adjunct to a company-provided health care plan. Small companies in particular use outside employee assistance programs, because they don’t have the needed expertise in-house. As their name implies, EAPs offer help in dealing with crises in the workplace and beyond. EAPs are often used to help workers who have substance abuse problems.

In Canada, a leading company, Lifeworks, offers such services in total wellbeing to clients to support the mental, physical, social and financial wellbeing of their people.

7.3 What Are Emotions?

Types of Emotions

Financial analysts measure the value of a company in terms of profits and stock. For employees, however, the value of a job is also emotional. The root of the word emotion comes from a French term meaning “to stir up.” And that’s a great place to begin our investigation of emotions at work. More formally, an emotion is defined as a short, intense feeling resulting from some event. Not everyone reacts to the same situation in the same way. For example, a manager’s way of speaking can cause one person to feel motivated, another to feel angry, and a third to feel sad. Emotions can influence whether a person is receptive to advice, whether they will quit a job, and how they will perform individually or on a team (Cole, Walter, & Bruch, 2008; George & Jones, 1996; Gino & Schweitzer, 2008). Of course, as you know, emotions can be positive or negative.

Positive emotions such as joy, love, and surprise result from our reaction to desired events. In the workplace, these events may include achieving a goal or receiving praise from a superior. Individuals experiencing a positive emotion may feel peaceful, content, and calm. A positive feeling generates a sensation of having something you didn’t have before. As a result, it may cause you to feel fulfilled and satisfied. Positive feelings have been shown to dispose a person to optimism, and a positive emotional state can make difficult challenges feel more achievable (Kirby, 2001). This is because being positive can lead to upward positive spirals where your good mood brings about positive outcomes, thereby reinforcing the good mood (Frederickson & Joiner, 2002).

Negative emotions such as anger, fear, and sadness can result from undesired events. In the workplace, these events may include not having your opinions heard, a lack of control over your day-to-day environment, and unpleasant interactions with colleagues, customers, and superiors. Negative emotions play a role in the conflict process, with those who can manage their negative emotions finding themselves in fewer conflicts than those who cannot.

The unwanted side effects of negative emotions at work are easy to see: an angry colleague is left alone to work through the anger; a jealous colleague is excluded from office gossip, which is also the source of important office news. But you may be surprised to learn that negative emotions can help a company’s productivity in some cases.

7.4 Emotions at Work

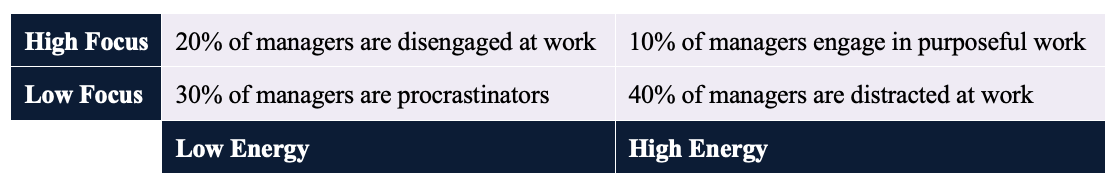

Graphic courtesy: David Steare, Pinterest

The graphic above indicates how the work environment influences the challenges and opportunities we face which could lead to positive or negative emotions and hence to job satisfaction and performance Our emotions are also impacted by our personality, the characteristics of which we studied in Chapter 3.

Emotions shape an individual’s belief about the value of a job, a company, or a team. Emotions also affect behaviours at work. Research shows that individuals within your own inner circle are better able to recognize and understand your emotions (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002).

So, what is the connection between emotions, attitudes, and behaviours at work? This connection may be explained using a theory named Affective Events Theory (AET). AET is a psychological model designed to explain the connection between emotions and feelings in the workplace and job performance, job satisfaction and behaviours. AET is underlined by a belief that human beings are emotional and that their behaviour is guided by emotion.

Researchers, Howard Weiss and Russell Cropanzano, studied the effects of six major kinds of emotions in the workplace: anger, fear, joy, love, sadness, and surprise (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Their theory argues that specific events on the job cause different kinds of people to feel different emotions. These emotions, in turn, inspire actions that can benefit or impede others at work (Fisher, 2002).

Jobs that are high in negative emotion can lead to frustration and burnout—an ongoing negative emotional state resulting from dissatisfaction (Lee & Ashforth, 1996; Maslach, 1982; Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Depression, anxiety, anger, physical illness, increased drug and alcohol use, and insomnia can result from frustration and burnout, with frustration being somewhat more active and burnout more passive. The effects of both conditions can impact coworkers, customers, and clients as anger boils over and is expressed in one’s interactions with others (Lewandowski, 2003).

Emotional Labour

The term was first coined by the sociologist Arlie Hochschild in her 1983 book on the topic, The Managed Heart. Emotional labor, as she conceived it, referred to the work of managing one’s own emotions that was required by certain professions. Flight attendants, who are expected to smile and be friendly even in stressful situations, is a key example. In recent years, the term’s popularity has grown immensely—in the United States Google searches for it are up, and it’s being mentioned more and more in books and academic articles.

Negative emotions are common among workers in service industries. Individuals who work in manufacturing rarely meet their customers face-to-face. If they’re in a bad mood, the customer would not know. Service jobs are just the opposite. Part of a service employee’s job is appearing a certain way in the eyes of the public. Individuals in service industries are professional helpers. As such, they are expected to be upbeat, friendly, and polite at all times, which can be exhausting to accomplish in the long run.

Humans are emotional creatures by nature. In the course of a day, we experience many emotions. Think about your day thus far. Can you identify times when you were happy to deal with other people and times that you wanted to be left alone? Now imagine trying to hide all the emotions you’ve felt today for 8 hours or more at work. That’s what cashiers, school teachers, massage therapists, fire fighters, and librarians, among other professionals, are asked to do. Emotional labour refers to the regulation of feelings and expressions for organizational purposes (Grandey, 2000).

Emotional Intelligence

One way to manage the effects of emotional labour is by increasing your awareness of the gaps between real emotions and emotions that are required by your professional persona. “What am I feeling? And what do others feel?” These questions form the heart of emotional intelligence. The term was coined by psychologists Peter Salovey and John Mayer and was popularized by psychologist Daniel Goleman in a book of the same name. Emotional intelligence looks at how people can understand each other more completely by developing an increased awareness of their own and others’ emotions (Carmeli, 2003).

You’ve seen them: The people who appear to be cool as a cucumber on deadline. Those who handle awkward family dinners with grace. The ones that get where you’re coming from, without you having to say a lot.

That’s because they may possess a certain skill set in spades — emotional intelligence.

Intelligence, in the general sense, is the ability to learn new concepts and apply your knowledge to problems. Emotional intelligence (EQ) is similar. It’s the ability to learn about yourself and apply that wisdom to the world around you.

Emotional Intelligence is different from other intelligences in that the focus is on emotioanl reasoning, ability and knowledge.

Daniel Goleman references 5 components in his book “Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ”

Self-awareness

If you’re self-aware, you can see your own patterns of behaviors and motives. You know how your emotions and actions impact those around you, for better or for worse. You can name your own emotions when they come up and understand why they’re there.

You can also recognize your triggers, identify your strengths, and see your own limitations.

Here’s an example:

Someone who is not self-aware encounters obstacles, sometimes the same ones repeatedly, and doesn’t understand why. Someone who is self-aware examines themselves honestly to get to the root of their problems.

Despite encountering the same problems, someone who’s self-aware is better equipped to deal with these obstacles.

Maybe people don’t like to talk to you. A person that isn’t self-aware would just get frustrated, or maybe not even notice that people are annoyed by them. A self-aware person examines the facts, and maybe admits (s)he rambles too much, doesn’t listen enough, isn’t engaging, or isn’t being present. They are better able to accept the situation, in order to then be more aware of what to improve.

In other words, the difference between someone who’s self-aware and someone who’s not is that one has the ability to diagnose the underlying issue.

Self-regulation

If you can self-regulate, your emotional reactions are in proportion to the given circumstances.

You know how to pause, as needed, and control your impulses. You think before you act and consider the consequences.

It also means you know how to ease tension, manage conflict, cope with difficult scenarios, and adapt to changes in your environment. It’s all about bringing out the part of yourself that helps manage emotions.

Self-regulation is a necessity for successful students. When it comes to test time, most people feel anxiety, which can be a demotivating factor. This is normal and expected. What’s important is how you implement self-regulation activities to ensure you study regularly.

One way to self-regulate while studying is to create a study diary. This will mean you have clear and exact dates when you need to sit down to study, which can prevent procrastination.

Another great self-regulation method for students is the Pomodoro technique. This technique involves setting a timer for 25 minutes and working on one task until the timer goes off. Then you take a five-minute break. After four rounds of this, you take a longer break of 20 or 30 minutes. This technique can help you stay focused and prevent burnout.

Motivation

If you’re intrinsically motivated, you have a thirst for personal development. You’re highly driven to succeed, whatever your version of success looks like.

You’re inspired to accomplish goals because it helps you grow as a person, rather than doing it for outside rewards like money, fame, status, or recognition.

Empathy

Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing .

If you’re empathic, you’re a healthy level of self-interested — but not self-centered.

In conversations, you can understand where someone is coming from. You can “walk a mile in their shoes,” so to speak. Even if the exact scenario hasn’t happened to you, you can draw on your life experience to imagine how it may feel and be compassionate about what they’re going through.

You’re slow to judge others and possess the awareness that we’re all just doing the best we can with the circumstances we’ve been given. When we know better, we do better.

Social skills

If you’ve developed your social skills, you’re adept at working in teams. You’re aware of others and their needs in a conversation or conflict resolution.

You’re welcoming in conversation, using active listening, eye contact, verbal communication skills, and open body language. You know how to develop a rapport with others or express leadership, if the occasion calls for it.

In the workplace, emotional intelligence can be used to form harmonious teams by taking advantage of the talents of every member. To accomplish this, colleagues well versed in emotional intelligence can look for opportunities to motivate themselves and inspire others to work together (Goleman, 1995). Chief among the emotions that helped create a successful team, Goleman learned, was empathy—the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes, whether that individual has achieved a major triumph or fallen short of personal goals (Goleman, 1998). Those high in emotional intelligence have been found to have higher self-efficacy in coping with adversity, perceive situations as challenges rather than threats, and have higher life satisfaction, which can all help lower stress levels (Law, Wong, & Song, 2004; Mikolajczak & Luminet, 2008).

Getting Emotional: The Case of American Express

Death and money can be emotional topics. Sales reps at American Express Company’s (NYSE: AXP) life insurance division had to deal with both these issues when selling life insurance, and they were starting to feel the strain of working with such volatile emotional materials every day. Part of the problem representatives faced seemed like an unavoidable side effect of selling life insurance. Many potential clients were responding fearfully to the sales representatives’ calls. Others turned their fears into anger. They replied to the representatives’ questions suspiciously or treated them as untrustworthy.

The sales force at American Express believed in the value of their work, but over time, customers’ negative emotions began to erode employee morale. Sales of policies slowed. Management insisted that the representatives ignore their customers’ feelings and focus on making sales. The representatives’ more aggressive sales tactics seemed only to increase their clients’ negative emotional responses, which kicked off the cycle of suffering again. It was apparent something had to change.

In an effort to understand the barriers between customers and sales representatives, a team led by Kate Cannon, a former American Express staffer and mental-health administrator, used a technique called emotional resonance to identify employees’ feelings about their work. Looking at the problem from an emotional point of view yielded dramatic insights about clients, sales representatives, and managers alike.

The first step she took was to acknowledge that the clients’ negative emotions were barriers to life insurance sales. Cannon explained, “People reported all kinds of emotional issues—fear, suspicion, powerlessness, and distrust—involved in buying life insurance.” Clients’ negative emotions, in turn, had sparked negative feelings among some American Express life insurance sales representatives, including feelings of incompetence, dread, untruthfulness, shame, and even humiliation. Management’s focus on sales had created an emotional disconnect between the sales reps’ work and their true personalities. Cannon discovered that sales representatives who did not acknowledge their clients’ distress felt dishonest. The emotional gap between their words and their true feelings only increased their distress.

Cannon also found some good news. Sales representatives who looked at their job from the customer’s point of view were flourishing. Their feelings and their words were in harmony. Clients trusted them. The trust between these more openly emotional sales representatives and their clients led to greater sales and job satisfaction. To see if emotional skills training could increase job satisfaction and sales among other members of the team, Cannon instituted a course in emotional awareness for a test group of American Express life insurance sales representatives. The goal of the course was to help employees recognize and manage their feelings. The results of the study proved the value of emotional clarity. Coping skills, as measured on standardized psychological tests, improved for the representatives who took Cannon’s course.

The emotional awareness training program had significant impact on American Express’s bottom line. Over time, as Cannon’s team expanded their emotion-based program, American Express life insurance sales rose by tens of millions of dollars. American Express’s exercise in emotional awareness shows that companies can profit when feelings are recognized and consciously managed. Employees whose work aligns with their true emotions make more believable corporate ambassadors. The positive use of emotion can benefit a company internally as well. According to a Gallup poll of over 2 million employees, the majority of workers rated a caring boss higher than increased salary or benefits. In the words of career expert and columnist Maureen Moriarty, “Good moods are good for business” (Kirkwood, 2002; Moriarty, 2007; Schwartz, 2008).

7.5 Conclusion

Stress is a major concern for individuals and organizations. Exhaustion is the outcome of prolonged stress. Individuals and organizations can take many approaches to lessening the negative health and work outcomes associated with being overstressed. Emotions play a role in organizational life. Understanding these emotions helps individuals to manage them. Emotional labour can be taxing on individuals, while emotional intelligence may help individuals cope with the emotional demands of their jobs.