Chapter 11: Making Decisions

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Understand what is involve in decision-making.

- Compare and contrast different decision-making models.

- Compare and contrast individual and group decision-making.

- Understand potential decision-making traps and how to avoid them.

- Understand the pros and cons of different decision-making aids.

- Engage in ethical decision making.

- Understand cross cultural differences in decision-making.

11.1 Decision-Making Culture: The Case of Google

Google (NASDAQ: GOOG) is one of the best-known and most admired companies around the world, so much so that “googling” is the term many use to refer to searching information on the web. What started out as a student project by two Stanford University graduates—Larry Page and Sergey Brin—in 1996, Google became the most frequently used web search engine on the internet with 1 billion searches per day in 2009, as well as other innovative applications such as Gmail, Google Earth, grew from 10 employees working in a garage in Palo Alto to 10,000 employees operating around the world by 2009. What is the formula behind this success?

Google strives to operate based on solid principles that may be traced back to its founders. In a world crowded with search engines, they were probably the first company that put users first. Their mission statement summarizes their commitment to end-user needs: “To organize the world’s information and to make it universally accessible and useful.” While other companies were focused on marketing their sites and increasing advertising revenues, Google stripped the search page of all distractions and presented users with a blank page consisting only of a company logo and a search box. Google resisted pop-up advertising, because the company felt that it was annoying to end-users. They insisted that all their advertisements would be clearly marked as “sponsored links.” This emphasis on improving user experience and always putting it before making more money in the short term seems to have been critical to their success.

Keeping their employees happy is also a value they take to heart. Google created a unique work environment that attracts, motivates, and retains the best players in the field. Google was ranked as the number 1 “Best Place to Work For” by Fortune magazine in 2007 and number 4 in 2010. This is not surprising if one looks closer at how Google treats employees. On their Mountain View, California, campus called the “Googleplex,” employees are treated to free gourmet food options including sushi bars and espresso stations. In fact, many employees complain that once they started working for Google, they tend to gain 10 to 15 pounds! Employees have access to gyms, shower facilities, video games, on-site child care, and doctors. Google provides 4 months of paternal leave with 75% of full pay and offers $500 for take-out meals for families with a newborn. These perks create a place where employees feel that they are treated well and their needs are taken care of. Moreover, they contribute to the feeling that they are working at a unique and cool place that is different from everywhere else they may have worked.

In addition, Google encourages employee risk taking and innovation. How is this done? When a vice president in charge of the company’s advertising system made a mistake costing the company millions of dollars and apologized for the mistake, she was commended by Larry Page, who congratulated her for making the mistake and noting that he would rather run a company where they are moving quickly and doing too much, as opposed to being too cautious and doing too little. This attitude toward acting fast and accepting the cost of resulting mistakes as a natural consequence of working on the cutting edge may explain why the company is performing much ahead of competitors such as Microsoft and Yahoo! One of the current challenges for Google is to expand to new fields outside of their web search engine business. To promote new ideas, Google encourages all engineers to spend 20% of their time working on their own ideas.

Google’s culture is reflected in their decision making as well. Decisions at Google are made in teams. Even the company management is in the hands of a triad: Larry Page and Sergey Brin hired Eric Schmidt to act as the CEO of the company, and they are reportedly leading the company by consensus. In other words, this is not a company where decisions are made by the senior person in charge and then implemented top down. It is common for several small teams to attack each problem and for employees to try to influence each other using rational persuasion and data. Gut feeling has little impact on how decisions are made. In some meetings, people reportedly are not allowed to say “I think…” but instead must say “the data suggests…” To facilitate teamwork, employees work in open office environments where private offices are assigned only to a select few. Even Kai-Fu Lee, the famous employee whose defection from Microsoft was the target of a lawsuit, did not get his own office and shared a cubicle with two other employees.

How do they maintain these unique values? In a company emphasizing hiring the smartest people, it is very likely that they will attract big egos that may be difficult to work with. Google realizes that its strength comes from its “small company” values that emphasize risk taking, agility, and cooperation. Therefore, they take their hiring process very seriously. Hiring is extremely competitive and getting to work at Google is not unlike applying to a college. Candidates may be asked to write essays about how they will perform their future jobs. Recently, they targeted potential new employees using billboards featuring brain teasers directing potential candidates to a web site where they were subjected to more brain teasers. Each candidate may be interviewed by as many as eight people on several occasions. Through this scrutiny, they are trying to select “Googley” employees who will share the company’s values, perform at high levels, and be liked by others within the company.

Will this culture survive in the long run? It may be too early to tell, given that the company was only founded in 1998. The founders emphasized that their initial public offering (IPO) would not change their culture and they would not introduce more rules or change the way things are done in Google to please Wall Street. But can a public corporation really act like a start-up? Can a global giant facing scrutiny on issues including privacy, copyright, and censorship maintain its culture rooted in its days in a Palo Alto garage? Larry Page is quoted as saying, “We have a mantra: don’t be evil, which is to do the best things we know how for our users, for our customers, for everyone. So I think if we were known for that, it would be a wonderful thing” (Elgin, Hof & Greene, 2005; Hardy, 2005; Mangalindan, 2004; Schoeneman, 2006; Warner, 2004).

11.2 Understanding Decision Making

Decision making refers to making choices among alternative courses of action—which may also include inaction. While it can be argued that management is decision making, half of the decisions made by managers within organizations ultimately fail (Ireland & Miller, 2004; Nutt, 2002; Nutt, 1999). Therefore, increasing effectiveness in decision making is an important part of maximizing your effectiveness at work. This chapter will help you understand how to make decisions alone or in a group while avoiding common decision-making pitfalls.

Types of Decisions

Most discussions of decision making assume that only senior executives make decisions or that only senior executives’ decisions matter. This is a dangerous mistake.

Despite the far-reaching nature of the decisions in the previous example, not all decisions have major consequences or even require a lot of thought. For example, before you come to class, you make simple and habitual decisions such as what to wear, what to eat, and which route to take as you go to and from home and school. You probably do not spend much time on these mundane decisions. These types of straightforward decisions are termed programmed decisions, or decisions that occur frequently enough that we develop an automated response to them. The automated response we use to make these decisions is called the decision rule. For example, many restaurants face customer complaints as a routine part of doing business. Because complaints are a recurring problem, responding to them may become a programmed decision. The restaurant might enact a policy stating that every time they receive a valid customer complaint, the customer should receive a free dessert, which represents a decision rule.

On the other hand, unique and important decisions require conscious thinking, information gathering, and careful consideration of alternatives. These are called nonprogrammed decisions. For example, in 2005 McDonald’s Corporation became aware of the need to respond to growing customer concerns regarding the unhealthy aspects (high in fat and calories) of the food they sell. This is a nonprogrammed decision, because for several decades, customers of fast-food restaurants were more concerned with the taste and price of the food, rather than its healthiness. In response to this problem, McDonald’s decided to offer healthier alternatives such as the choice to substitute French fries in Happy Meals with apple slices and in 2007 they banned the use of trans fat at their restaurants.

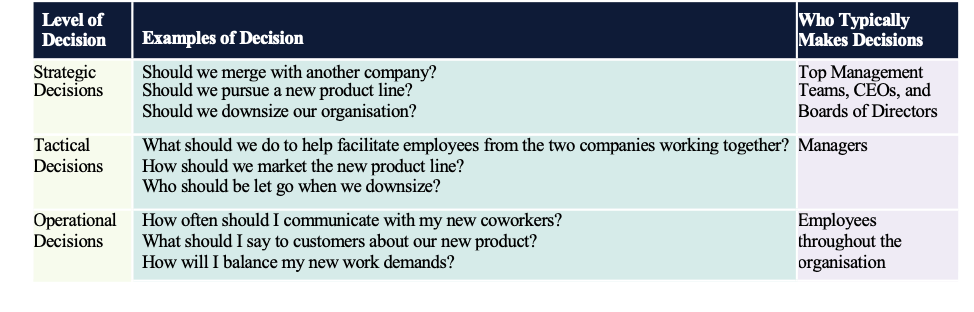

Decisions can be classified into three categories based on the level at which they occur. Strategic decisions set the course of an organization. Tactical decisions are decisions about how things will get done. Finally, operational decisions refer to decisions that employees make each day to make the organization run. For example, think about the restaurant that routinely offers a free dessert when a customer complaint is received. The owner of the restaurant made a strategic decision to have great customer service. The manager of the restaurant implemented the free dessert policy as a way to handle customer complaints, which is a tactical decision. Finally, the servers at the restaurant are making individual decisions each day by evaluating whether each customer complaint received is legitimate and warrants a free dessert.

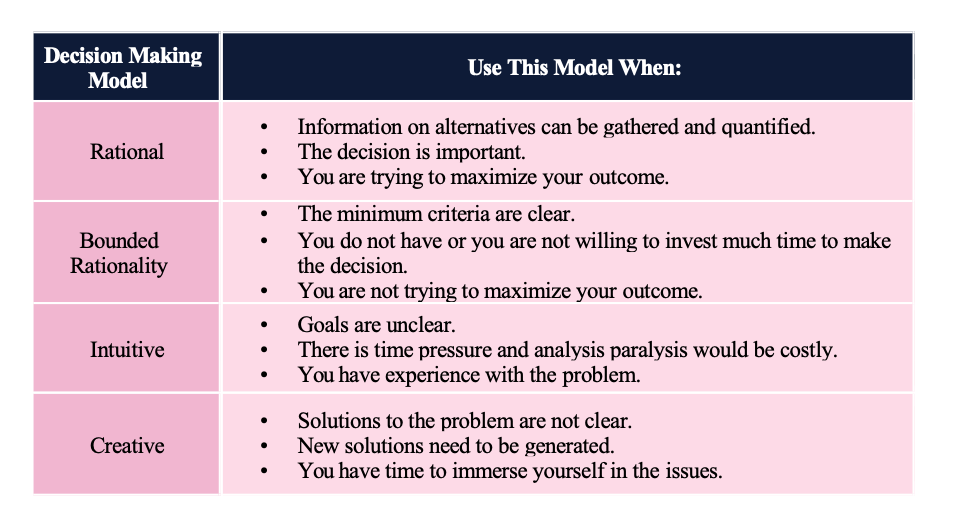

In this chapter, we are going to discuss different decision-making models designed to understand and evaluate the effectiveness of nonprogrammed decisions. We will cover four decision-making approaches, starting with the rational decision-making model, moving to the bounded rationality decision-making model, the intuitive decision-making model, and ending with the creative decision-making model.

Making Rational Decisions

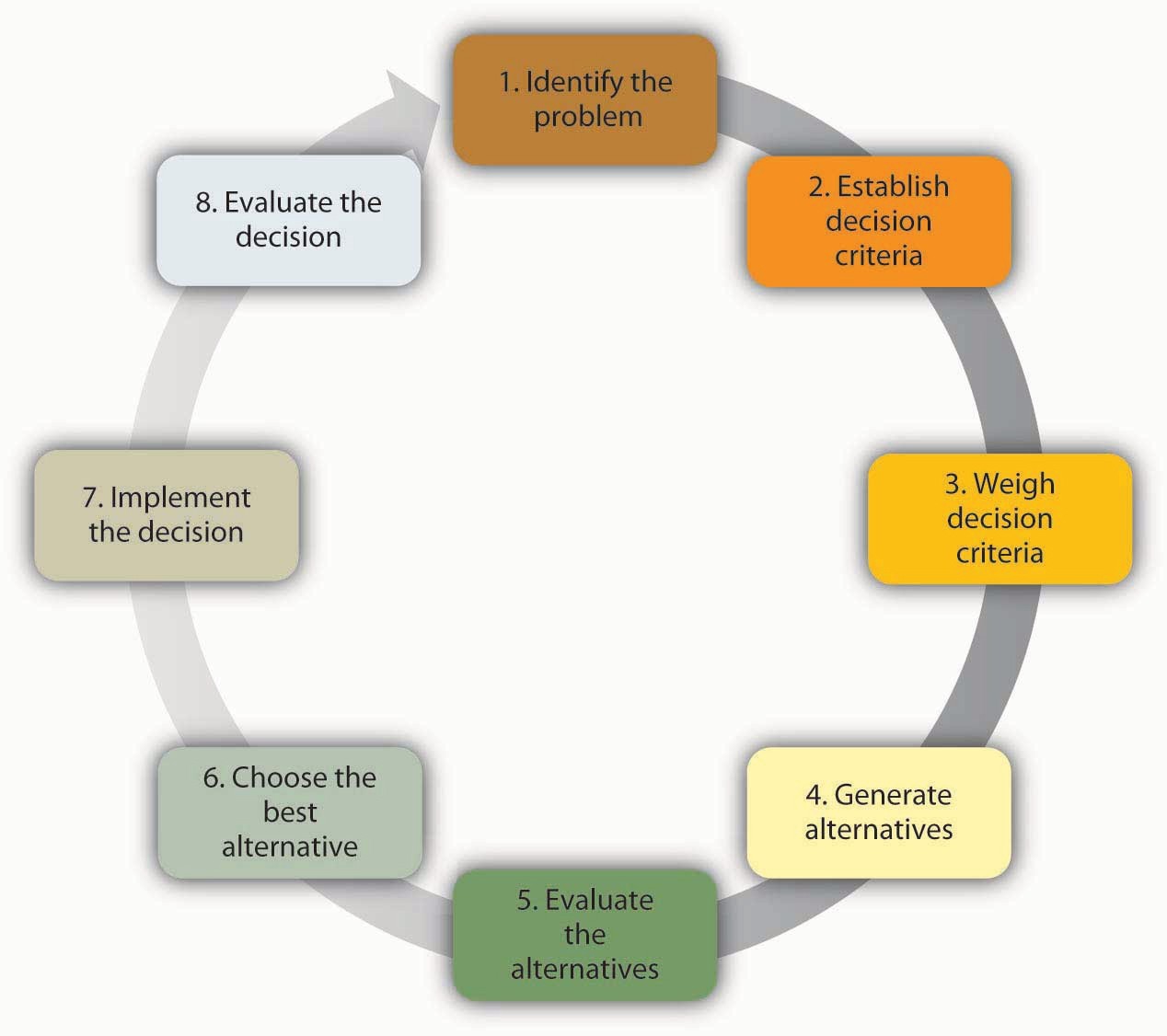

The rational decision-making model describes a series of steps that decision makers should consider if their goal is to maximize the quality of their outcomes. In other words, if you want to make sure that you make the best choice, going through the formal steps of the rational decision-making model may make sense.

Let’s imagine that your old, clunky car has broken down, and you have enough money saved for a substantial down payment on a new car. It will be the first major purchase of your life, and you want to make the right choice. The first step, therefore, has already been completed—we know that you want to buy a new car. Next, in step 2, you’ll need to decide which factors are important to you. How many passengers do you want to accommodate? How important is fuel economy to you? Is safety a major concern? You only have a certain amount of money saved, and you don’t want to take on too much debt, so price range is an important factor as well. If you know you want to have room for at least five adults, get at least 20 miles per gallon, drive a car with a strong safety rating, not spend more than $22,000 on the purchase, and like how it looks, you have identified the decision criteria. All the potential options for purchasing your car will be evaluated against these criteria. Before we can move too much further, you need to decide how important each factor is to your decision in step 3. If each is equally important, then there is no need to weigh them, but if you know that price and mpg are key factors, you might weigh them heavily and keep the other criteria with medium importance. Step 4 requires you to generate all alternatives about your options. Then, in step 5, you need to use this information to evaluate each alternative against the criteria you have established. You choose the best alternative (step 6), and then you would go out and buy your new car (step 7).

Of course, the outcome of this decision will influence the next decision made. That is where step 8 comes in. For example, if you purchase a car and have nothing but problems with it, you will be less likely to consider the same make and model when purchasing a car the next time.

While decision makers can get off track during any of these steps, research shows that searching for alternatives in the fourth step can be the most challenging and often leads to failure. In fact, one researcher found that no alternative generation occurred in 85% of the decisions he studied (Nutt, 1994).

Conversely, successful managers know what they want at the outset of the decision-making process, set objectives for others to respond to, carry out an unrestricted search for solutions, get key people to participate, and avoid using their power to push their perspective (Nutt, 1998).

The rational decision-making model has important lessons for decision makers. First, when making a decision, you may want to make sure that you establish your decision criteria before you search for alternatives. This would prevent you from liking one option too much and setting your criteria accordingly. For example, let’s say you started browsing cars online before you generated your decision criteria. You may come across a car that you feel reflects your sense of style and you develop an emotional bond with the car. Then, because of your love for the particular car, you may say to yourself that the fuel economy of the car and the innovative braking system are the most important criteria. After purchasing it, you may realize that the car is too small for your friends to ride in the back seat, which was something you should have thought about. Setting criteria before you search for alternatives may prevent you from making such mistakes. Another advantage of the rational model is that it urges decision makers to generate all alternatives instead of only a few. By generating a large number of alternatives that cover a wide range of possibilities, you are unlikely to make a more effective decision that does not require sacrificing one criterion for the sake of another.

Despite all its benefits, you may have noticed that this decision-making model involves a number of unrealistic assumptions as well. It assumes that people completely understand the decision to be made, that they know all their available choices, that they have no perceptual biases, and that they want to make optimal decisions. Nobel Prize winning economist Herbert Simon observed that while the rational decision-making model may be a helpful device in aiding decision makers when working through problems, it doesn’t represent how decisions are frequently made within organizations. In fact, Simon argued that it didn’t even come close.

Making “Good Enough” Decisions

The bounded rationality model of decision making recognizes the limitations of our decision-making processes. According to this model, individuals knowingly limit their options to a manageable set and choose the first acceptable alternative without conducting an exhaustive search for alternatives. An important part of the bounded rationality approach is the tendency to satisfice (a term coined by Herbert Simon from satisfy and suffice), which refers to accepting the first alternative that meets your minimum criteria. For example, many college graduates do not conduct a national or international search for potential job openings. Instead, they focus their search on a limited geographic area, and they tend to accept the first offer in their chosen area, even if it may not be the ideal job situation. Satisficing is similar to rational decision making. The main difference is that rather than choosing the best option and maximizing the potential outcome, the decision maker saves cognitive time and effort by accepting the first alternative that meets the minimum threshold.

Making Intuitive Decisions

The intuitive decision-making model has emerged as an alternative to other decision making processes. This model refers to arriving at decisions without conscious reasoning. A total of 89% of managers surveyed admitted to using intuition to make decisions at least sometimes and 59% said they used intuition often (Burke & Miller, 1999). Managers make decisions under challenging circumstances, including time pressures, constraints, uncertainty, changing conditions, and high visibility, and high stakes outcomes. Thus, it makes sense that they would not have the time to use the rational decision-making model. Yet when CEOs, financial analysts, and health care workers are asked about the critical decisions they make, seldom do they attribute success to luck. To an outside observer, it may seem like they are making guesses as to the course of action to take, but it turns out that experts systematically make decisions using a different model than was earlier suspected. Research on life-or-death decisions made by fire chiefs, pilots, and nurses finds that experts do not choose among a list of well thought out alternatives. They don’t decide between two or three options and choose the best one. Instead, they consider only one option at a time. The intuitive decision-making model argues that in a given situation, experts making decisions scan the environment for cues to recognize patterns (Breen, 2000; Klein, 2003; Salas & Klein, 2001). Once a pattern is recognized, they can play a potential course of action through to its outcome based on their prior experience.

Making Creative Decisions

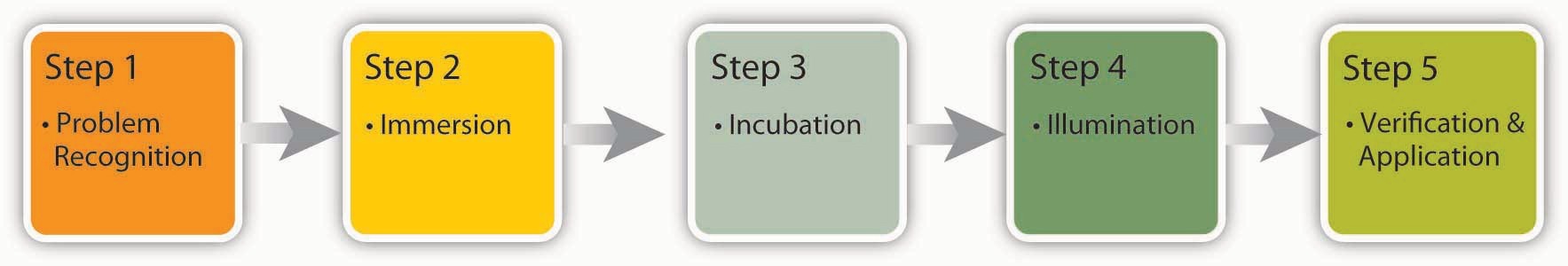

In addition to the rational decision making, bounded rationality, and intuitive decision-making models, creative decision making is a vital part of being an effective decision maker. Creativity is the generation of new, imaginative ideas. With the flattening of organizations and intense competition among companies, individuals and organizations are driven to be creative in decisions ranging from cutting costs to generating new ways of doing business. Please note that, while creativity is the first step in the innovation process, creativity and innovation are not the same thing. Innovation begins with creative ideas, but it also involves realistic planning and follow-through. Innovations such as 3M’s Clearview Window Tinting grow out of a creative decision-making process about what may or may not work to solve real-world problems.

The five steps to creative decision making are similar to the previous decision-making models in some key ways. All the models include problem identification, which is the step in which the need for problem solving becomes apparent. If you do not recognize that you have a problem, it is impossible to solve it. Immersion is the step in which the decision maker consciously thinks about the problem and gathers information. A key to success in creative decision making is having or acquiring expertise in the area being studied. Then, incubation occurs. During incubation, the individual sets the problem aside and does not think about it for a while. At this time, the brain is actually working on the problem unconsciously. Then comes illumination, or the insight moment when the solution to the problem becomes apparent to the person, sometimes when it is least expected. This sudden insight is the “eureka” moment, similar to what happened to the ancient Greek inventor Archimedes, who found a solution to the problem he was working on while taking a bath. Finally, the verification and application stage happen when the decision maker consciously verifies the feasibility of the solution and implements the decision.

A NASA scientist describes his decision-making process leading to a creative outcome as follows: He had been trying to figure out a better way to de-ice planes to make the process faster and safer. After recognizing the problem, he immersed himself in the literature to understand all the options, and he worked on the problem for months trying to figure out a solution. It was not until he was sitting outside a McDonald’s restaurant with his grandchildren that it dawned on him. The golden arches of the M of the McDonald’s logo inspired his solution—he would design the deicer as a series of Ms. This represented the illumination stage. After he tested and verified his creative solution, he was done with that problem, except to reflect on the outcome and process.

11.3 Faulty Decision Making

Avoiding Decision-Making Traps

No matter which model you use, it is important to know and avoid the decision-making traps that exist. Daniel Kahnemann (another Nobel Prize winner) and Amos Tversky spent decades studying how people make decisions. They found that individuals are influenced by overconfidence bias, hindsight bias, anchoring bias, framing bias, and escalation of commitment.

Overconfidence bias occurs when individuals overestimate their ability to predict future events. Many people exhibit signs of overconfidence. For example, 82% of the drivers surveyed feel they are in the top 30% of safe drivers, 86% of students at the Harvard Business School say they are better looking than their peers, and doctors consistently overestimate their ability to detect problems (Tilson, 1999). Much like friends that are 100% sure they can pick the winners of this week’s football games despite evidence to the contrary, these individuals are suffering from overconfidence bias. Similarly, in 2008, the French bank Société Générale lost over $7 billion as a result of the rogue actions of a single trader. Jérôme Kerviel, a junior trader in the bank, had extensive knowledge of the bank’s control mechanisms and used this knowledge to beat the system. Interestingly, he did not make any money from these transactions himself, and his sole motive was to be successful. He secretly started making risky moves while hiding the evidence. He made a lot of profit for the company early on and became overly confident in his abilities to make even more. In his defense, he was merely able to say that he got “carried away” (The rogue rebuttal, 2008). People who purchase lottery tickets as a way to make money are probably suffering from overconfidence bias. It is three times more likely for a person driving 10 miles to be killed in a car accident than to win the jackpot (Orkin, 1991).

Hindsight bias is the opposite of overconfidence bias, as it occurs when looking backward in time and mistakes seem obvious after they have already occurred. In other words, after a surprising event occurred, many individuals are likely to think that they already knew the event was going to happen. This bias may occur because they are selectively reconstructing the events. Hindsight bias tends to become a problem when judging someone else’s decisions. For example, let’s say a company driver hears the engine making unusual sounds before starting the morning routine. Being familiar with this car in particular, the driver may conclude that the probability of a serious problem is small and continues to drive the car. During the day, the car malfunctions and stops miles away from the office. It would be easy to criticize the decision to continue to drive the car because in hindsight, the noises heard in the morning would make us believe that the driver should have known something was wrong and taken the car in for service. However, the driver in question may have heard similar sounds before with no consequences, so based on the information available at the time, continuing with the regular routine may have been a reasonable choice. Therefore, it is important for decision makers to remember this bias before passing judgments on other people’s actions.

Anchoring refers to the tendency for individuals to rely too heavily on a single piece of information. Job seekers often fall into this trap by focusing on a desired salary while ignoring other aspects of the job offer such as additional benefits, fit with the job, and working environment. Similarly, but more dramatically, lives were lost in the Great Bear Wilderness Disaster when the coroner, within 5 minutes of arriving at the accident scene, declared all five passengers of a small plane dead, which halted the search effort for potential survivors. The next day two survivors who had been declared dead walked out of the forest. How could a mistake like this have been made? One theory is that decision biases played a large role in this serious error, and anchoring on the fact that the plane had been consumed by flames led the coroner to call off the search for any possible survivors (Becker, 2007).

Framing bias is another concern for decision makers. Framing bias refers to the tendency of decision makers to be influenced by the way that a situation or problem is presented. For example, when making a purchase, customers find it easier to let go of a discount as opposed to accepting a surcharge, even though they both might cost the person the same amount of money. Similarly, customers tend to prefer a statement such as “85% lean beef” as opposed to “15% fat” (Li, Sun & Wang, 2007). It is important to be aware of this tendency, because depending on how a problem is presented to us, we might choose an alternative that is disadvantageous simply because of the way it is framed.

Escalation of commitment occurs when individuals continue on a failing course of action after infor-mation reveals it may be a poor path to follow. It is sometimes called the “sunken costs fallacy,” because continuation is often based on the idea that one has already invested in the course of action. For example, imagine a person who purchases a used car, which turns out to need something repaired every few weeks. An effective way of dealing with this situation might be to sell the car without incurring further losses, donate the car, or use it until it falls apart. However, many people would spend hours of their time and hundreds, even thousands of dollars repairing the car in the hopes that they might recover their initial investment. Thus, rather than cutting their losses, they waste time and energy while trying to justify their purchase of the car.

Why does escalation of commitment occur? There may be many reasons, but two are particularly important. First, decision makers may not want to admit that they were wrong. This may be because of personal pride or being afraid of the consequences of such an admission. Second, decision makers may incorrectly believe that spending more time and energy might somehow help them recover their losses. Effective decision makers avoid escalation of commitment by distinguishing between when persistence may actually pay off versus when it might mean escalation of commitment. To avoid escalation of commitment, you might consider having strict turning back points. For example, you might determine up front that you will not spend more than $500 trying to repair the car and will sell it when you reach that point. You might also consider assigning separate decision makers for the initial buying and subsequent selling decisions. Periodic evaluations of an initially sound decision to see whether the decision still makes sense is also another way of preventing escalation of commitment. This type of review becomes particularly important in projects such as the Iridium phone, in which the initial decision is not immediately implemented but instead needs to go through a lengthy development process. In such cases, it becomes important to periodically assess the soundness of the initial decision in the face of changing market conditions. Finally, creating an organizational climate in which individuals do not fear admitting that their initial decision no longer makes economic sense would go a long way in preventing escalation of commitment, as it could lower the regret the decision maker may experience (Wong & Kwong, 2007).

So far we have focused on how individuals make decisions and how to avoid decision traps. Next we shift our focus to the group level. There are many similarities as well as many differences between individual and group decision making. There are many factors that influence group dynamics and also affect the group decision-making process. We will discuss some of them in the following section.

11.4 Decision Making in Groups

When it Comes to Decision Making, are two Heads Better Than One?

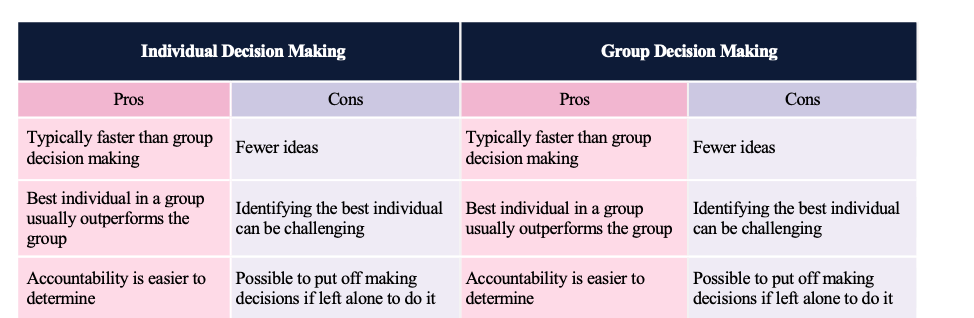

The answer to this question depends on several factors. Group decision making has the advantage of drawing from the experiences and perspectives of a larger number of individuals. Hence, a group may have the potential to be more creative and lead to more effective decisions. In fact, groups may sometimes achieve results beyond what they could have done as individuals. Groups may also make the task more enjoyable for the members. Finally, when the decision is made by a group rather than a single individual, implementation of the decision will be easier, because group members will be more invested in the decision. If the group is diverse, better decisions may be made, because different group members may have different ideas based on their backgrounds and experiences. Research shows that for top management teams, diverse groups that debate issues make decisions that are more comprehensive and better for the bottom line (Simons, Pelled, & Smith, 1999).

Despite its popularity within organizations, group decision making suffers from a number of disadvantages. We know that groups rarely outperform their best member (Miner, 1984). While groups have the potential to arrive at an effective decision, they often suffer from process losses. For example, groups may suffer from coordination problems. Anyone who has worked with a team of individuals on a project can attest to the difficulty of coordinating members’ work or even coordinating everyone’s presence in a team meeting. Furthermore, groups can suffer from groupthink. Finally, group decision making takes more time compared to individual decision making, because all members need to discuss their thoughts regarding different alternatives.

Thus, whether an individual or a group decision is preferable will depend on the specifics of the situation. For example, if there is an emergency and a decision needs to be made quickly, individual decision making might be preferred. Individual decision making may also be appropriate if the individua; in question has all the information needed to make the decision and if implementation problems are not expected. On the other hand, if one person does not have all the information and skills needed to make a decision, if implementing the decision will be difficult without the involvement of those who will be affected by the decision, and if time urgency is more modest, then decision making by a group may be more effective.

Groupthink

Have you ever been in a decision-making group that you felt was heading in the wrong direction but you didn’t speak up and say so? If so, you have already been a victim of groupthink. Groupthink is a tendency to avoid a critical evaluation of ideas the group favors. Iriving Janis, author of a book called Victims of Groupthink, explained that groupthink is characterized by eight

- Illusion of invulnerability is shared by most or all of the group members, which creates excessive optimism and encourages them to take extreme risks.

- Collective rationalizations occur, in which members downplay negative information or warnings that might cause them to reconsider their assumptions.

- An unquestioned belief in the group’s inherent morality occurs, which may incline members to ignore ethical or moral consequences of their actions.

- Stereotyped views of outgroups are seen when groups discount rivals’ abilities to make effective responses.

- Direct pressure is exerted on any members who express strong arguments against any of the group’s stereotypes, illusions, or commitments.

- Self-censorship occurs when members of the group minimize their own doubts and counter-arguments.

- Illusions of unanimity occur, based on self-censorship and direct pressure on the group. The lack of dissent is viewed as unanimity.

- The emergence of self-appointed mind guards happens when one or more members protect the group from information that runs counter to the group’s assumptions and course of action.

Tools and Techniques for Making Better Decisions

Nominal Group Technique (NGT) was developed to help with group decision making by ensuring that all members participate fully. NGT is not a technique to be used routinely at all meetings. Rather, it is used to structure group meetings when members are grappling with problem solving or idea generation. It follows four steps (Delbecq, Van de Ven, & Gustafson, 1975). First, each member of the group begins by independently and silently writing down ideas. Second, the group goes in order around the room to gather all the ideas that were generated. This process continues until all the ideas are shared. Third, a discussion takes place around each idea, and members ask for and give clarification and make evaluative statements. Finally, group members vote for their favourite ideas by using ranking or rating techniques. Following the four-step NGT helps to ensure that all members participate fully, and it avoids group decision-making problems such as groupthink.

Delphi Technique is unique because it is a group process using written responses to a series of questionnaires instead of physically bringing individuals together to make a decision. The first questionnaire asks individuals to respond to a broad question such as stating the problem, outlining objectives, or proposing solutions. Each subsequent questionnaire is built from the information gathered in the previous one. The process ends when the group reaches a consensus. Facilitators can decide whether to keep responses anonymous. This process is often used to generate best practices from experts. For example, Purdue University Professor Michael Campion used this process when he was editor of the research journal Personnel Psychology and wanted to determine the qualities that distinguished a good research article. Using the Delphi technique, he was able to gather responses from hundreds of top researchers from around the world and distill them into a checklist of criteria that he could use to evaluate articles submitted to his journal, all without ever having to leave his office (Campion, 1993).

Majority rule refers to a decision-making rule in which each member of the group is given a single vote and the option receiving the greatest number of votes is selected. This technique has remained popular, perhaps due to its simplicity, speed, ease of use, and representational fairness. Research also supports majority rule as an effective decision-making technique (Hastie & Kameda, 2005). However, those who did not vote in favor of the decision will be less likely to support it.

Consensus is another decision-making rule that groups may use when the goal is to gain support for an idea or plan of action. While consensus tends to require more time, it may make sense when support is needed to enact the plan. The process works by discussing the issues at hand, generating a proposal, calling for consensus, and discussing any concerns. If concerns still exist, the proposal is modified to accommodate them. These steps are repeated until consensus is reached. Thus, this decision-making rule is inclusive, participatory, cooperative, and democratic. Research shows that consensus can lead to better accuracy (Roch, 2007), and it helps members feel greater satisfaction with decisions (Mohammed & Ringseis, 2001). However, groups take longer with this approach, and if consensus cannot be reached, members tend to become frustrated (Peterson, 1999).

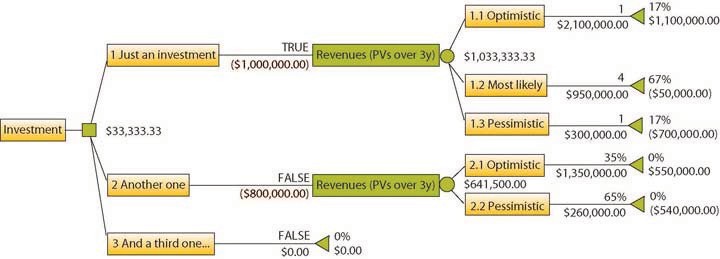

Decision trees are diagrams in which answers to yes or no questions lead decision makers to address additional questions until they reach the end of the tree. Decision trees are helpful in avoiding errors such as framing bias (Wright & Goodwin, 2002). Decision trees tend to be helpful in guiding the decision maker to a predetermined alternative and ensuring consistency of decision making—that is, every time certain conditions are present, the decision maker will follow one course of action as opposed to others if the decision is made using a decision tree.

11.5 The Roles of Ethics and National Culture

Ethics and Decision Making

Because many decisions involve an ethical component, one of the most important considerations in management is whether the decisions you are making as an employee or manager are ethical. Here are some basic questions you can ask yourself to assess the ethics of a decision (Blanchard & Peale, 1988).

- Is this decision fair?

- Will I feel better or worse about myself after I make this decision?

- Does this decision break any organizational rules?

- Does this decision break any laws?

- How would I feel if this decision were broadcasted on the news?

The current economic crisis in the United States and many other parts of the world is a perfect example of legal yet unethical decisions resulting in disaster. Many experts agree that one of the driving forces behind the sliding economy was the lending practices of many banks (of which several no longer exist). In March of 2008, a memo from JPMorgan Chase & Co. was leaked to an Oregon newspaper called “Zippy Cheats & Tricks” (Zippy is Chase’s automated, computer-based loan approval system). Although Chase executives firmly stated that the contents of the memo were not company policy, the contents clearly indicate some of the questionable ethics involved with the risky loans now clogging the financial system.

In the memo, several steps were outlined to help a broker push a client’s approval through the system, including, “In the income section of your 1003, make sure you input all income in base income. DO NOT break it down by overtime, commissions or bonus. NO GIFT FUNDS! If your borrower is getting a gift, add it to a bank account along with the rest of the assets. Be sure to remove any mention of gift funds on the rest of your 1003. If you do not get Stated/Stated, try resubmitting with slightly higher income. Inch it up $500 to see if you can get the findings you want. Do the same for assets” (Manning, 2008).

While it is not possible to determine how widely circulated the memo was, the mentality it captures was clearly present during the lending boom that precipitated the current meltdown. While some actions during this period were distinctly illegal, many people worked well within the law and simply made unethical decisions. Imagine a real estate agent that knows a potential buyer’s income. The buyer wants to purchase a home priced at $400,000, and the agent knows the individual cannot afford to make payments on a mortgage of that size. Instead of advising the buyer accordingly and losing a large commission, the agent finds a bank willing to lend money to an unqualified borrower, collects the commission for the sale, and moves on to the next client. It is clear how these types of unethical yet legal decisions can have dramatic consequences.

Suppose you are the CEO of a small company that needs to cut operational costs or face bankruptcy. You have decided that you will not be issuing the yearly bonus that employees have come to expect. The first thing you think about after coming to this decision is whether or not it is fair. It seems logical to you that since the alternative would be the failure of the company and everyone losing their jobs, not receiving a bonus is preferable to being out of work. Additionally, you will not be collecting a bonus yourself, so that the decision will affect everyone equally. After deciding that the decision seems fair, you try to assess how you will feel about yourself after informing employees that there will not be a bonus this year. Although you do not like the idea of not being able to issue the yearly bonus, you are the CEO, and CEOs often have to make tough decisions. Since your ultimate priority is to save the company from bankruptcy, you decide it is better to withhold bonuses rather than issuing them, knowing the company cannot afford it. Despite the fact that bonuses have been issued every year since the company was founded, there are no organizational policies or laws requiring that employees receive a bonus; it has simply been a company tradition. The last thing you think about is how you would feel if your decision were broadcast on the news. Because of the dire nature of the situation, and because the fate of the business is at stake, you feel confident that this course of action is preferable to laying off loyal employees. As long as the facts of the situation were reported correctly, you feel the public would understand why the decision was made.

Decision Making Around the Globe

Decision-making styles and approaches tend to differ depending on the context, and one important contextual factor to keep in mind is the culture in which decisions are being made. Research on Japanese and Dutch decision makers show that while both cultures are consensus-oriented, Japanese managers tend to seek consensus much more than Dutch managers (Noorderhaven, 2007). Additionally, American managers tend to value quick decision making, while Chinese managers are more reflective and take their time to make important decisions—especially when they involve some sort of potential conflict.

Another example of how decision-making styles may differ across cultures is the style used in Japan called nemawashi. Nemawashi refers to building consensus within a group before a decision is made. Japanese decision makers talk to parties whose support is needed beforehand, explain the subject, address their concerns, and build their support. Using this method clearly takes time and may lead to slower decision making. However, because all parties important to the decision will give their stamp of approval before the decision is made, this technique leads to a quicker implementation of the final decision once it is decided.

11.6 Mini Case Scenario

WHO DO YOU HIRE? ENSURE THAT YOUR DECISION IS THE RIGHT

Your organization, Lux Hotel & Spa, has a strong commitment to diversity and inclusion. This commitment is regularly communicated by leadership and your direct manager. The organization has taken concrete steps to increase diversity and inclusion, such as diversity training, embedding diversity into annual performance measures and setting “soft” targets for diversity in hiring. You’re the hotel food and beverage manager for Lux’s Toronto location. As part of your duties, you’re responsible for hiring, coordinating and supervising food service staff. You’re looking for a cook for one of the three onsite restaurants and have interviewed a number of candidates. You have narrowed it down to two candidates. Both are recent graduates of George Brown College’s culinary program and have part-time experience working in restaurants while in school. Both interview well and seem well-suited for the role. In the context of this decision, the hotel’s metrics identified a gap in women chefs and cooks. There are no women chefs at Lux Toronto, and only 15% of Lux Toronto’s cooks are women. It’s also close to year-end performance reviews. At your mid-year review, your boss had asked what you are doing, or planning to do, to increase the level of diversity within food and beverage as the diversity numbers have remained unchanged in your area. You hate to admit this but you’re concerned that the woman candidate won’t work the long and late evening hours required in the restaurant. Your experience has been that many women cannot or do not want to commit in the same way men once they have children. Who do you hire? Why? Were there any steps you could have taken before and after the recruitment and hiring stage to ensure your decision is a good one?

WHO DO YOU HIRE?

The Twist

Your boss asks you to present to the Executive Committee your personal philosophy about diversity hiring, the challenges you face, and how you plan to address them.

What are the key points of your presentation in light of the decision you just made?

©Ted Rogers Leadership Centre. This case is made available for public use under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivs (CC BY-NC-ND) license.

Empowered Decision Making: The Case of Ingar Skaug

“If you always do what you always did, you always get what you always got,” says Ingar Skaug—and he should know. Skaug is president and CEO of Wilh. Wilhelmsen ASA (OSE: ABM), a leading global maritime industry company based in Norway with 23,000 employees and 516 offices worldwide. He faced major challenges when he began his job at Wilhelmsen Lines in 1989. The entire top management team of the company had been killed in an airplane crash when returning from a ship dedication ceremony. As you can imagine, employees were mourning the loss of their friends and leadership team. While Skaug knew that changes needed to be made within the organization, he also knew that he had to proceed slowly and carefully in implementing any changes. The biggest challenge he saw was the decision-making style within the company.

Skaug recalls this dilemma as follows:

I found myself in a situation in Wilhelmsen Lines where everyone was coming to my office in the morning and they expected me to take all the decisions. I said to people, “Those are not my decisions. I don’t want to take those decisions. You take those decisions.” So for half a year they were screaming about that I was very afraid of making decisions. So I had a little bit of a struggle with the organization, with the people there at the time. They thought I was a very poor manager because I didn’t dare to make decisions. I had to teach them. I had to force the people to make their own decisions.

His lessons paid off over the years. The company has now invented a cargo ship capable of transporting 10,000 vehicles while running exclusively on renewable energy via the power of the sun, wind, and water. He and others within the company cite the freedom that employees feel to make decisions and mistakes on their way to making discoveries as a major factor in their success in revolutionizing the shipping industry one innovation at a time (Furness, 2005; McCarthy et al., 2005; Norwegian, 2006).

11.7 Conclusion

Decision making is a critical component of business. Some decisions are obvious and can be made quickly without investing much time and effort in the decision-making process. Others, however, require substantial consideration of the circumstances surrounding the decision, available alternatives, and potential outcomes. Fortunately, there are several methods that can be used when making a difficult decision, depending on various environmental factors. Some decisions are best made by groups. Group decision-making processes also have multiple models to follow, depending on the situation. Even when specific models are followed, groups and individuals can often fall into potential decision-making pitfalls. If too little information is available, decisions might be made based on a feeling. On the other hand, if too much information is presented, people can suffer from analysis paralysis, in which no decision is reached because of the overwhelming number of alternatives.

Ethics and culture both play a part in decision making. From time to time, a decision can be legal but not ethical. These gray areas that surround decision making can further complicate the process, but following basic guidelines can help people ensure that the decisions they make are ethical and fair. Additionally, different cultures can have different styles of decision making. In some countries such as the United States, it may be customary to come to a simple majority when making a decision. Conversely, a country such as Japan will often take the time to reach consensus when making decisions. Being aware of the various methods for making decisions as well as potential problems that may arise can help people become effective decision makers in any situation.

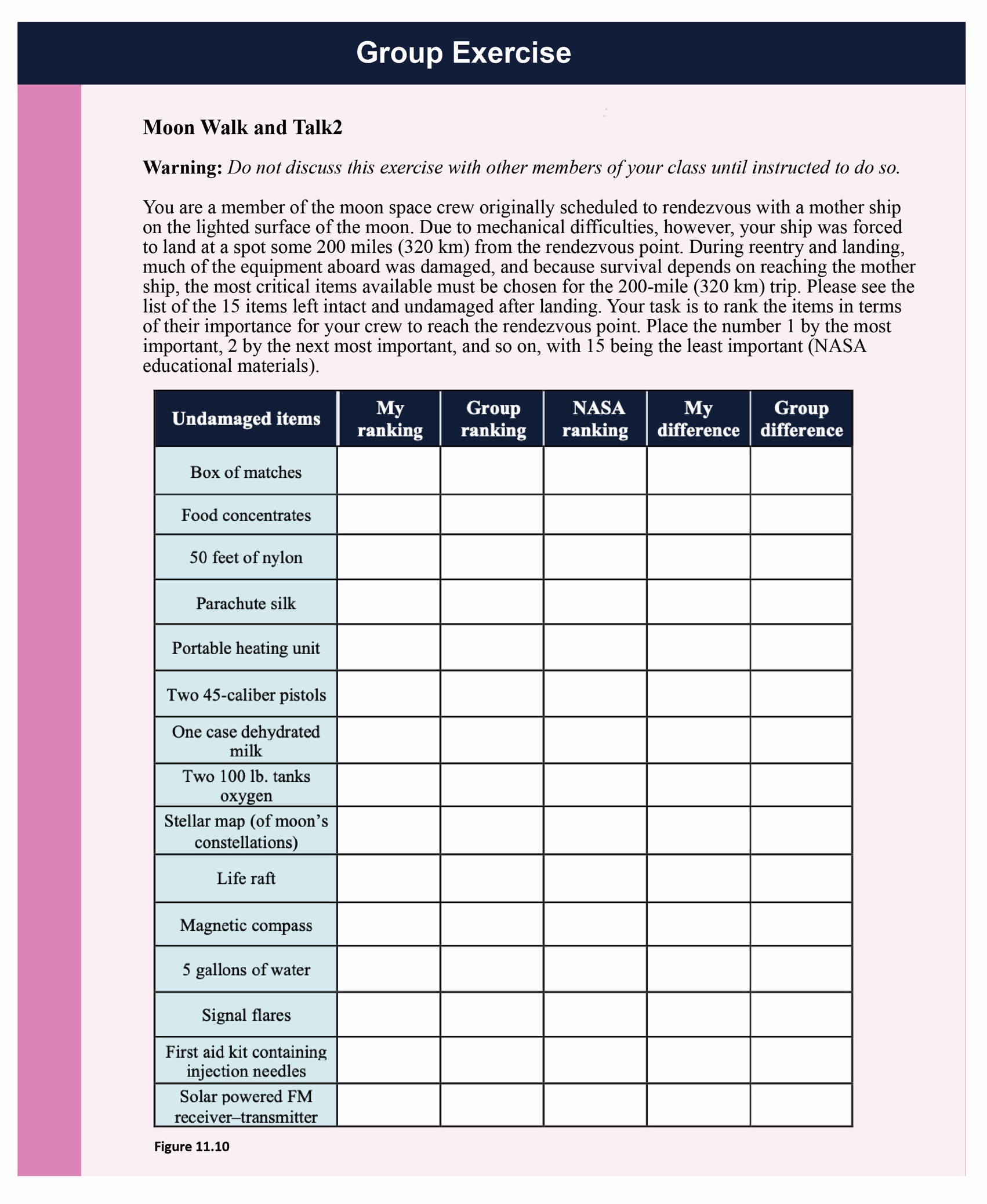

11.8 Exercises