Chapter 5: Theories of Motivation

Chapter Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you should be able to know and learn the following:

- Understand the role of motivation in determining employee performance.

- Classify the basic needs of employees.

- Describe how fairness perceptions are determined and consequences of these perceptions.

- Understand the importance of rewards and punishments.

- Apply motivation theories to analyze performance problems.

Introduction

The challenges and motivators in a post pandemic world.

The world is becoming progressively more digital with every passing year, so today’s workforce looks a lot different than it did 25 years ago. This progression, expedited by the global pandemic of Covid19, presents new challenges that today’s employers must learn to navigate to motivate their teams, prevent employee burnout and minimize turnover.

To understand and overcome the challenges in motivating today’s workforce, especially companies with significant numbers of non-desk workers, we must understand both the challenges and the motivators of new age, digital employees.

Let’s start with the challenges.

The top challenges chosen by the vast majority of employers

A. Building a great employee experience

1.Listen to people. Ensure that employees have a means of communication. Many non-desk workers are not connected to the company in a way that allows two-way communication.

2.Get feedback from surveys and focus groups, then implement change if need be. Keep an open channel of communication so that employees feel connected. Be committed to employee development and growth.

3.Equip and enable managers to support their teams. Creating a positive employee experience goes a long way with employee engagement and motivation.

B. Creating calm and reassurance in periods of turbulence

1.We can all agree that the world has been in a period of turbulence over the past two years. As a leader in an organization, you must pause and breathe. Managers can unintentionally pass their stress onto other employees.

2.Do the research and prevent the spread of misinformation. Speak clearly and confidently to your teams and colleagues so that you appear to have control over the situation. Transparency will create trust and go a long way in calming the workforce.

C. Fighting burnout

1.Let’s talk about the ever-elusive fight against burnout. It’s easy to understand that the outside stressors of everyday life during and after a pandemic paired with the daily stressors of work are enough to burn anyone out. More than 70% of employees reported feeling burnt out over the past year, making history (Forbes.com).

2.It’s never been more critical than it is now to tackle feelings of physical and emotional exhaustion. The key to avoiding burnout is getting in front of it, as it is much easier to prevent burnout than reverse it.

D. Turnover and letting employees go

1.Turnover tends to be a result of a poor approach to the above challenges. It’s no secret that the cost of turnover is high, estimated at 1.5 – 2 times an employee’s salary and $1,500 per hourly employee (builtin.com).

Therefore, organizations should actively avoid turnover by putting into place best practices and implementing a solid plan to tackle the above challenges.

E. Retaining top talent

1.With the cost of turnover being so high, retaining top talent is a priority. The key here is employee engagement, so ask questions to gain insight on employees to instill the correct development and training programs.

Weekly one-on-one meetings with department heads or managers are an excellent way to ask questions and get to know these individuals. Including all employees in the communication loop creates an atmosphere of teamwork and ensures that everyone’s efforts are appreciated.

2.Create on-the-job learning opportunities, whether significant or small. Vary learning experiences and provide insightful feedback that is constructive and accompanied by manageable action steps.

F. Communicating effectively

These challenges arguably have a common denominator – they’re a causal effect of poor communication. Therefore, effective communication could essentially eliminate or solve these challenges.

It seems simple, yet effective communication is complex and involves complex solutions. Everyone communicates differently. The good news is there are a plethora of companies specializing in making communications in the workforce easy.

According to Pew Research, 91% of Americans between the ages of 18 and 64 own a smartphone, making them far and away the most popular way to communicate. Due to this information, the most innovative and easiest way to reach employees and increase engagement would be to interact via the smartphone.

Employee engagement apps can simplify your workforce management system and workplace communication making it accessible for all employees, non-desk workers, remote and office workers alike. Some of these platforms include Artificial Intelligence which provides highly structured communications.

These communications give the right message to the right person at the right time, prevent spray and pray messaging, and the chaos and lack of usage that reply-all messaging creates.

Now that the challenges have been addressed, let’s understand the motivators.

Why is it that, on some days, it can feel harder than others to get up when your alarm goes off, do your workout, complete a work or school assignment, or make dinner for your family?

Motivation (or a lack thereof) is usually behind why we do the things that we do.

There are different types of motivation, and as it turns out, understanding why you are motivated to do the things that you do can help you keep yourself motivated — and can help you motivate others.

There are two types of motivator categories in a company’s culture, intrinsic and extrinsic.

What Is Intrinsic Motivation?

When you’re intrinsically motivated, your behavior is motivated by your internal desire to do something for its own sake — for example, your personal enjoyment of an activity, or your desire to learn a skill because you’re eager to learn.

Examples of intrinsic motivation could include:

- Reading a book because you enjoy the storytelling

- Exercising because you want to relieve stress

- Cleaning your home because it helps you feel organized

What Is Extrinsic Motivation?

When you’re extrinsically motivated, your behavior is motivated by an external factor pushing you to do something in hopes of earning a reward — or avoiding a less-than-positive outcome.

Examples of extrinsic motivation could include:

- Reading a book to prepare for a test

- Exercising to lose weight

- Cleaning your home to prepare for visitors coming over

If you have a job, and you must complete a project, you’re probably extrinsically motivated — by your manager’s praise or a potential raise or commission — even if you enjoy the project while you’re doing it. If you’re in school, you’re extrinsically motivated to learn a foreign language because you’re being graded on it — even if you enjoy practicing and studying it.

So, intrinsic motivation is good, and extrinsic motivation is good. The key is to figure out why you — and your team — are motivated to do things and encouraging both types of motivation.

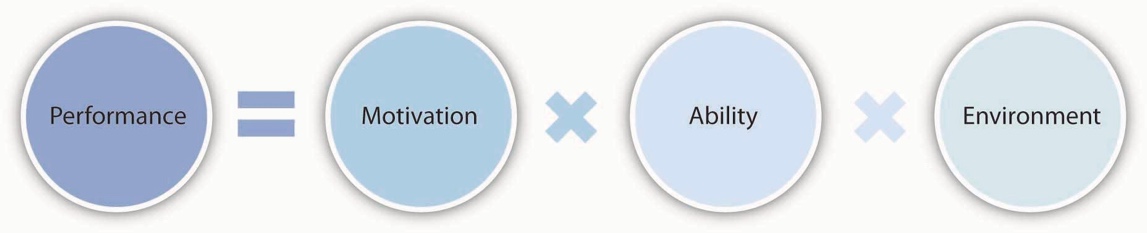

If someone is not performing well, what could be the reason? According to this equation, motivation, ability, and environment are the major influences over employee performance.

Motivation is one of the forces that lead to performance. Motivation is defined as the desire to achieve a goal or a certain performance level, leading to goal-directed behaviour. When we refer to someone as being motivated, we mean that the person is trying hard to accomplish a certain task. Motivation is clearly important if someone is to perform well; however, it is not sufficient. Ability—or having the skills and knowledge required to perform the job—is also important and is sometimes the key predictor of effectiveness. Finally, environmental factors such as having the resources, information, and support to perform well are critical to determine performance. At different times, one of these three factors may be the key to high performance. For example, for an employee sweeping the floor, motivation may be the most important factor that determines performance. In contrast, even the most motivated individual would not be able to successfully design a house without the necessary talent involved in building quality homes. Being motivated is not the same as being a high performer and is not the sole reason why people perform well, but it is nevertheless a key influence over our performance level.

So, what motivates people? Why do some employees try to reach their targets and pursue excellence while others merely show up at work and count the hours? As with many questions involving human beings, the answer is anything but simple. Instead, there are several theories explaining the concept of motivation. We will discuss motivation theories under two categories: need-based theories and process theories.

5.1 A Motivating Place to Work: The Case of Rogers Communications Inc

Rogers Communications Inc has been identified as one of Canada’s 100 top employers by Media Corp Canada, who investigate Canadian companies based on 8 criteria: (1) Physical Workplace; (2) Work Atmosphere & Social; (3) Health, Financial & Family Benefits; (4) Vacation & Time Off; (5) Employee Communications; (6) Performance Management; (7) Training & Skills Development; and (8) Community Involvement. Employers are compared to other organizations in their field to determine which offers the most progressive and forward-thinking programs (Media Corp Canada,2019).

5.2 Need-Based Theories of Motivation

Early researchers thought that employees try hard and demonstrate behaviour to satisfy their own personal needs. For example, an employee who is always walking around the office talking to people may have a need for companionship, and his or her behaviour may be a way of satisfying this need. At the time, researchers developed theories to understand what people need. Two theories may be placed under this category: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and McClelland’s acquired-needs theory.

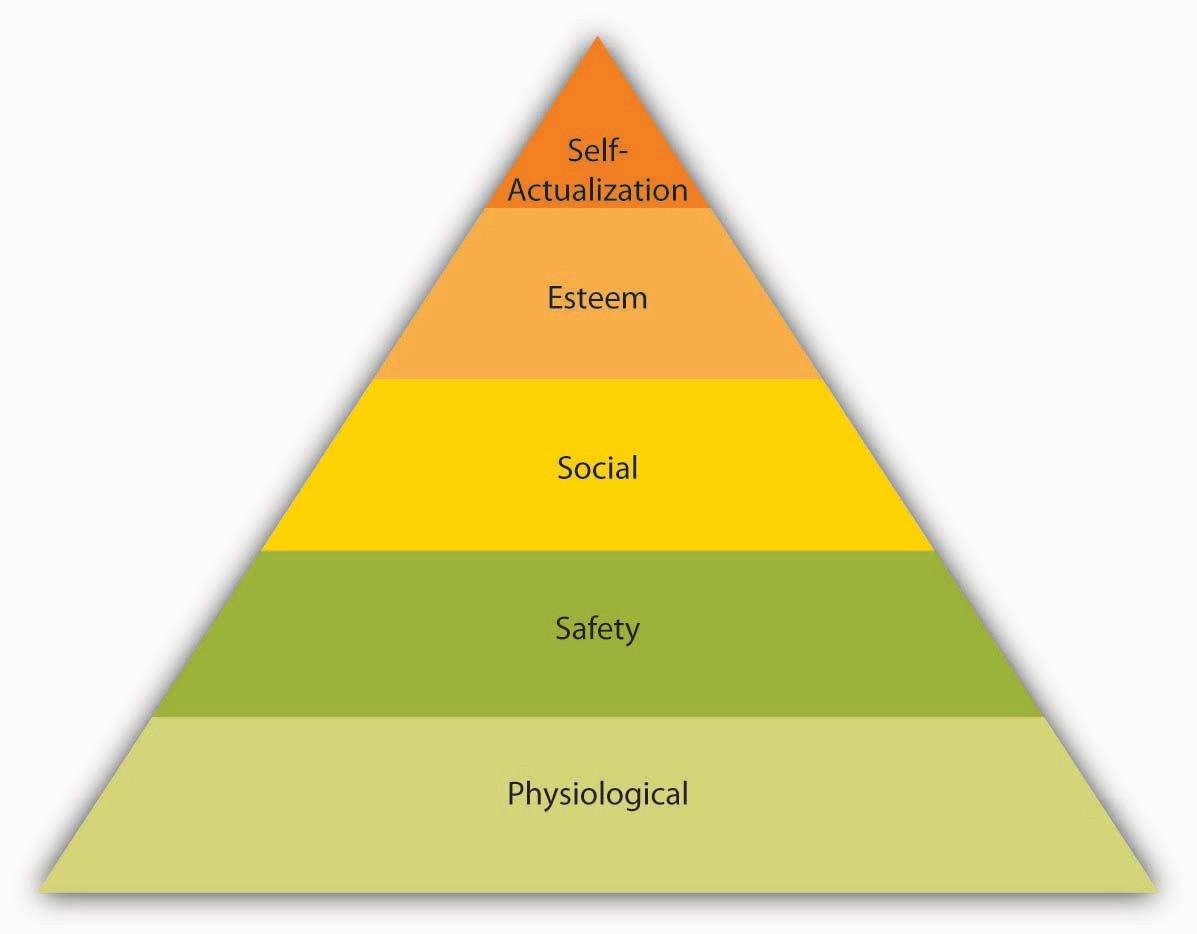

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Abraham Maslow is among the most prominent psychologists of the twentieth century. His hierarchy of needs is an image familiar to most business students and managers. The theory is based on a simple idea: human beings have needs that are ranked (Maslow, 1943; Maslow, 1954). There are some needs that are basic to all human beings, and in their absence nothing else matters. As we satisfy these basic needs, we start looking to satisfy higher order needs. In other words, once a lower-level need is satisfied, it no longer serves as a motivator.

The most basic of Maslow’s needs are physiological needs. Physiological needs refer to the need for food, water, and other biological needs. These needs are basic because when they are lacking, the search for them may overpower all other urges. Imagine being very hungry. At that point, all your behaviour may be directed at finding food. Once you eat, though, the search for food ceases and the promise of food no longer serves as a motivator. Once physiological needs are satisfied, people tend to become concerned about safety needs. Are they free from the threat of danger, pain, or an uncertain future? On the next level up, social needs refer to the need to bond with other human beings, be loved, and form lasting attachments with others. In fact, attachments, or lack of them, are associated with our health and well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). The satisfaction of social needs makes esteem needs more salient. Esteem needs refer to the desire to be respected by one’s peers, feel important, and be appreciated. Finally, at the highest level of the hierarchy, the need for self-actualization refers to “becoming all you are capable of becoming.” This need manifests itself by the desire to acquire new skills, take on new challenges, and behave in a way that will lead to the attainment of one’s life goals.

How can an organization satisfy its employees’ various needs? In the long run, physiological needs may be satisfied by the person’s paycheck, but it is important to remember that pay may satisfy other needs such as safety and esteem as well. Providing generous benefits that include health insurance and company-sponsored retirement plans, as well as offering a measure of job security, will help satisfy safety needs. Social needs may be satisfied by having a friendly environment and providing a workplace conducive to collaboration and communication. Company picnics and other social get-togethers may also be helpful if most employees are motivated primarily by social needs (but may cause resentment if they are not and if they must sacrifice a Sunday afternoon for a company picnic). Providing promotion opportunities at work, recognizing a person’s accomplishments verbally or through more formal reward systems, and conferring job titles that communicate to the employee that one has achieved high status within the organization are among the ways of satisfying esteem needs. Finally, self-actualization needs may be satisfied by the provision of development and growth opportunities on or off the job, as well as by work that is interesting and challenging. By making the effort to satisfy the different needs of each employee, organizations may ensure a highly motivated workforce.

Acquired-Needs Theory

Among the need-based approaches to motivation, David McClelland’s acquired-needs theory is the one that has received the greatest amount of support. According to this theory, individuals acquire three types of needs because of their life experiences. These needs are the need for achievement, the need for affiliation, and the need for power. All individuals possess a combination of these needs, and the dominant needs are thought to drive employee behaviour.

McClelland used a unique method called the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) to assess the dominant need (Spangler, 1992). This method entails presenting research subjects an ambiguous picture and asking them to write a story based on it. The instructions will be: “Take a look at the following picture. Who is this person? What is she doing? Why is she doing it?” The story you tell about the woman in the picture would then be analyzed by trained experts. The idea is that the stories the photo evokes would reflect how the mind works and what motivates the person. (Apperception: the mental process by which a person makes sense of an idea by assimilating it to the body of ideas he or she already possesses. For example: a perception would be seeing a dog and thinking “There is a dog.” Apperception would be seeing a dog and thinking “That dog looks like the one that bit my friend Andres”)

If the story you come up with contains themes of success, meeting deadlines, or coming up with brilliant ideas, you may be high in need for achievement. Those who have high need for achievement have a strong need to be successful. As children, they may be praised for their hard work, which forms the foundations of their persistence (Mueller & Dweck, 1998). As adults, they are preoccupied with doing things better than they did in the past. These individuals are constantly striving to improve their performance. They relentlessly focus on goals, particularly stretch goals that are challenging in nature (Campbell, 1982).

Are individuals who are high in need for achievement effective managers? Because of their success in lower-level jobs where their individual contributions matter the most, those with high need for achievement are often promoted to higher level positions (McClelland & Boyatzis, 1982). However, a high need for achievement has significant disadvantages in management positions. Management involves getting work done by motivating others.

If the story you created in relation to the picture you are analyzing contains elements of making plans to be with friends or family, you may have a high need for affiliation. Individuals who have a high need for affiliation want to be liked and accepted by others. When given a choice, they prefer to interact with others and be with friends (Wong & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991).

Finally, if your story contains elements of getting work done by influencing other people or the desire to make an impact on the organization, you may have a high need for power. Those with a high need for power want to influence others and control their environment. A need for power may in fact be a destructive element in relationships with colleagues if it takes the form of seeking and using power for one’s own good and prestige.

5.3 Process-Based Theories

A separate stream of research views motivation as something more than action aimed at satisfying a need. Instead, process-based theories view motivation as a logical process. Individuals analyze their work environment, develop thoughts and feelings, and react in certain ways. Process theories attempt to explain the thought processes of individuals who demonstrate motivated behaviour. Under this category, we will review equity theory, expectancy theory, and reinforcement theory.

Equity Theory

Imagine that you are paid $10 an hour working as an office assistant. You have held this job for 6 months. You are very good at what you do, you come up with creative ways to make things easier around you, and you are a good colleague who is willing to help others. You stay late when necessary and are flexible if requested to change hours. Now imagine that you found out they are hiring another employee who is going to work with you, who will hold the same job title, and who will perform the same type of tasks. This person has more advanced computer skills, but it is unclear whether these will be used on the job. The starting pay for this person will be $14 an hour. How would you feel? Would you be as motivated as before, going above and beyond your duties?

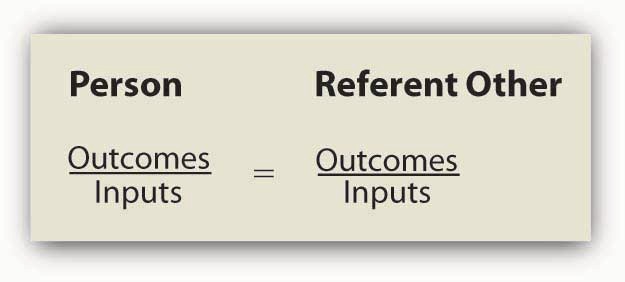

If your reaction to this scenario is along the lines of “this would be unfair,” your behaviour may be explained using equity theory (Adams, 1965). According to this theory, individuals are motivated by a sense of fairness in their interactions. Moreover, our sense of fairness is a result of the social comparisons we make. Specifically, we compare our inputs and outcomes with other people’s inputs and outcomes. We perceive fairness if we believe that the input-to-outcome ratio we are bringing into the situation is like the input-to-outcome ratio of a comparison person, or a referent. Perceptions of inequity create tension within us and drive us to action that will reduce perceived inequity.

What Are Inputs and Outcomes?

Inputs are the contributions people feel they are making to the environment. In the previous example, the person’s hard work; loyalty to the organization; amount of time with the organization; and level of education, training, and skills may have been relevant inputs. Outcomes are the perceived rewards someone can receive from the situation. For the hourly wage employee in our example, the $10 an hour pay rate was a core outcome. There may also be other, more peripheral outcomes, such as acknowledgment or preferential treatment from a manager. In the prior example, however, the person may reason as follows: I have been working here for 6 months. I am loyal, and I perform well (inputs). I am paid $10 an hour for this (outcomes). The new person does not have any experience here (referent’s inputs) but will be paid $14 an hour. This situation is unfair.

Who is the Referent?

The referent other may be a specific person as well as a category of people. Referents should be comparable to us—otherwise the comparison is not meaningful. It would be pointless for a student worker to compare himself to the CEO of the company, given the differences in inputs and outcomes. Instead, individuals may compare themselves to someone performing similar tasks within the same organization or, in the case of a CEO, a different organization.

Reactions to Unfairness

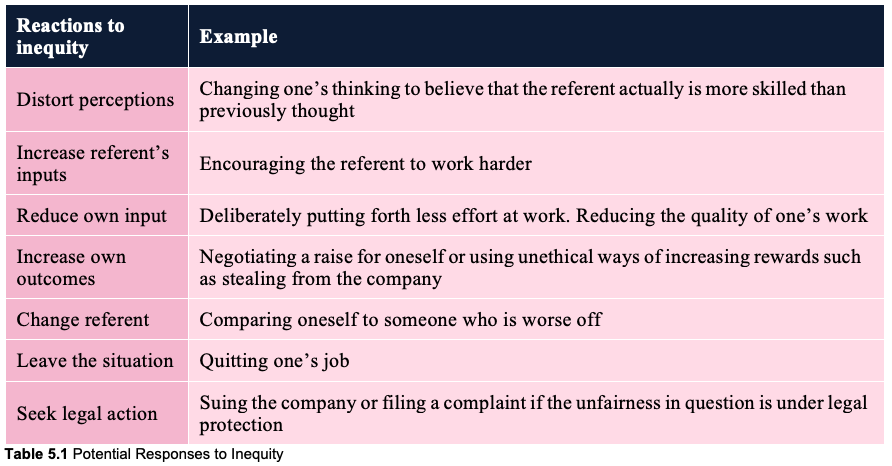

The theory outlines several potential reactions to perceived inequity. Oftentimes, the situation may be dealt with perceptually by altering our perceptions of our own or the referent’s inputs and outcomes. For example, we may justify the situation by downplaying our own inputs (I don’t really work very hard on this job), valuing our outcomes more highly (I am gaining valuable work experience, so the situation is not that bad), distorting the other person’s inputs (the new hire really is more competent than I am and deserves to be paid more), or distorting the other person’s outcomes (she gets $14 an hour but will have to work with a lousy manager, so the situation is not unfair).

Another option would be to have the referent increase inputs. If the other person brings more to the situation, getting more out of the situation would be fair. If that person can be made to work harder or work on more complicated tasks, equity would be achieved.

The person experiencing a perceived inequity may also reduce inputs or attempt to increase outcomes. If the lower paid person puts forth less effort, the perceived inequity would be reduced. Research shows that people who perceive inequity reduce their work performance or reduce the quality of their inputs (Carrell & Dittrich, 1978; Goodman & Friedman, 1971). Increasing one’s outcomes can be achieved through legitimate means such as negotiating a pay raise. At the same time, research shows that those feeling inequity sometimes resort to stealing to balance the scales (Greenberg, 1993).

Other options include changing the comparison person (e.g., others doing similar work in different organizations are paid only minimum wage) and leaving the situation by quitting (Schmidt & Marwell, 1972). Sometimes it may be necessary to consider taking legal action as a potential outcome of perceived inequity. For example, if an employee finds out the main reason behind a pay gap is gender related, the person may react to the situation by taking legal action because sex discrimination in pay is illegal in Canada.

Fairness Beyond Equity: Procedural and Interactional Justice

Equity theory looks at perceived fairness as a motivator. However, the way equity theory defines fairness is limited to fairness of rewards. Starting in the 1970s, research on workplace fairness began taking a broader view of justice. Equity theory deals with outcome fairness, and therefore it is considered to be a distributive justice theory.

Distributive justice refers to the degree to which the outcomes received from the organization are perceived to be fair. Two other types of fairness have been identified: procedural justice and interactional justice.

Let’s assume that you just found out you are getting a promotion. Clearly, this is an exciting outcome and comes with a pay raise, increased responsibilities, and prestige. If you feel you deserve to be promoted, you will perceive high distributive justice (you getting this promotion is fair). However, you later found out upper management picked your name out of a hat! What would you feel? You might still like the outcome but feel that the decision-making process was unfair. If so, you are describing feelings of procedural justice.

Procedural justice refers to the degree to which fair decision-making procedures are used to arrive at a decision. People do not care only about reward fairness. They also expect decision-making processes to be fair. In fact, research shows that employees care about the procedural justice of many organizational decisions, including layoffs, employee selection, surveillance of employees, performance appraisals, and pay decisions (Alge, 2001; Bauer et al., 1998; Kidwell, 1995). People also tend to care more about procedural justice in situations in which they do not get the outcome they feel they deserve (Brockner & Wiesenfeld, 1996). If you did not get the promotion and later discovered that management chose the candidate by picking names out of a hat, how would you feel? This may be viewed as adding insult to injury. When people do not get the rewards they want, they tend to hold management responsible if procedures are not fair (Brockner et al., 2007).

Now let’s imagine the moment your boss told you that you are getting a promotion. Your manager’s exact words were, “Yes, we are giving you the promotion. The job is so simple that we thought even you can handle it.” Now what is your reaction? The feeling of unfairness you may now feel is explained by interactional justice. Interactional justice refers to the degree to which people are treated with respect, kindness, and dignity in interpersonal interactions. We expect to be treated with dignity by our peers, supervisors, and customers. When the opposite happens, we feel angry. Even when faced with negative outcomes such as a pay cut, being treated with dignity and respect serves as a buffer and alleviates our stress (Greenberg, 2006).

Expectancy Theory

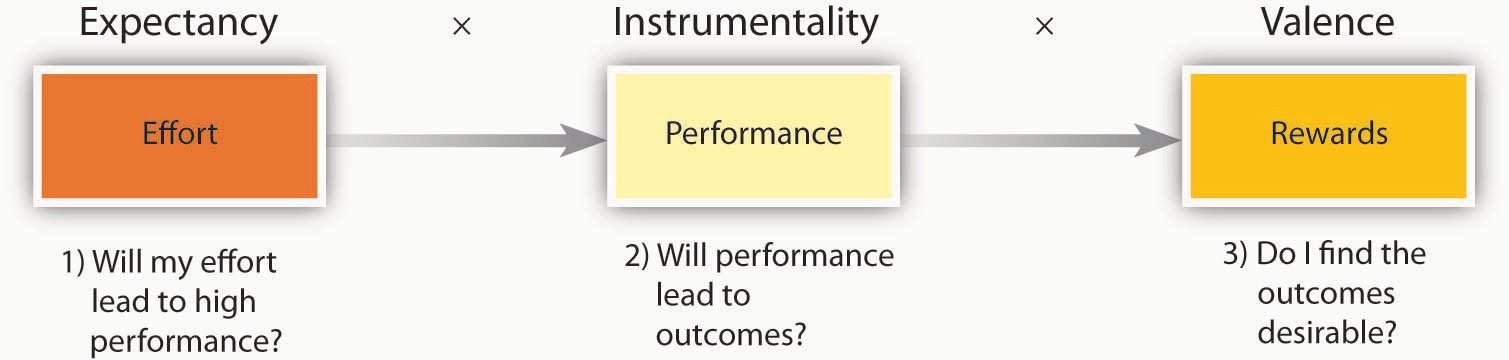

The expectancy theory of motivation, or the expectancy theory, is the belief that an individual chooses their behaviors based on what they believe leads to the most beneficial outcome. The individual’s motivation to put forth more or less effort is determined by a rational calculation in which individuals evaluate their situation (Porter & Lawler, 1968; Vroom, 1964).

This theory is dependent on how much value a person places on different motivations. This results in a decision they expect to give them the highest return for their efforts.

According to this theory, individuals ask themselves three questions.

The first question is whether the person believes that high levels of effort will lead to outcomes of interest, such as performance or success. This perception is labeled expectancy. For example, do you believe that the effort you put forth in a class is related to performing well in that class? If you do, you are more likely to put forth effort.

The second question is the degree to which the person believes that performance is related to subsequent outcomes, such as rewards. This perception is labeled instrumentality. For example, do you believe that getting a good grade in the class is related to rewards such as getting a better job, or gaining approval from your instructor, or from your friends or parents? If you do, you are more likely to put forth effort.

Finally, individuals are also concerned about the value of the rewards awaiting them as a result of performance. The anticipated satisfaction that will result from an outcome is labeled valence. For example, do you value getting a better job, or gaining approval from your instructor, friends, or parents? If these outcomes are desirable to you, your expectancy and instrumentality is high, and you are more likely to put forth effort.

Expectancy theory is a well-accepted theory that has received a lot of research attention (Heneman & Schwab, 1972; Van Eerde & Thierry, 1996). It is simple and intuitive. Consider the following example. Let’s assume that you are working in the concession stand of a movie theater. You have been selling an average of 100 combos of popcorn and soft drinks a day. Now your manager asks you to increase this number to 300 combos a day. Would you be motivated to try to increase your numbers? Here is what you may be thinking:

- Expectancy: is the belief that if an individual raises their efforts, their reward may rise as well. Expectancy is what motivates a person to gather the right tools to get the job done, which could include raw materials and resources, skills to perform the job and support and information from supervisors. Can I do it? If I try harder, can I really achieve this number? Is there a link between how hard I try and whether I reach this goal or not? If you feel that you can achieve this number if you try, you have high expectancy.

- Instrumentality: is the belief that the reward you receive depends on your performance in the workplace. What is in it for me? What is going to happen if I reach 300? What are the outcomes that will follow? Are they going to give me a 2% pay raise? Am I going to be named the salesperson of the month? Am I going to receive verbal praise from my manager? If you believe that performing well is related to certain outcomes, instrumentality is high.

- Valence: is the importance you place on the expected outcome of your performance. This often depends on your individual needs, goals, values and sources of motivation. For example, if you expect to be one of the top performers on your team, you may place high importance on achieving that goal, even if others don’t expect you to achieve this level of performance. How do I feel about the outcomes in question? Do I feel that a 2% pay raise is desirable? Do I find being named the salesperson of the month attractive? Do I think that being praised by my manager is desirable? If your answers are yes, valence is positive. In contrast, if you find the outcomes undesirable (you definitely do not want to be named the salesperson of the month because your friends would make fun of you), valence is negative.

If your answers to all three questions are affirmative—you feel that you can do it, you will get an outcome if you do it, and you value the reward—you are more likely to be motivated to put forth more effort toward selling more combos.

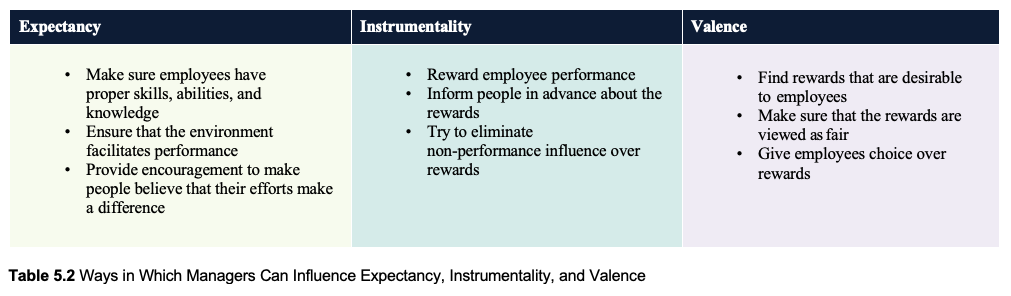

As a manager, how can you motivate employees? In fact, managers can influence all three perceptions (Cook, 1980).

Influencing Expectancy Perceptions

Employees may not believe that their effort leads to high performance for a multitude of reasons. First, they may not have the skills, knowledge, or abilities to successfully perform their jobs. The answer to this problem may be training employees or hiring people who are qualified for the jobs in question. Second, low levels of expectancy may be because employees may feel that something other than effort predicts performance, such as political behaviours on the part of employees. If employees believe that the work environment is not conducive to performing well (resources are lacking or roles are unclear), expectancy will also suffer. Therefore, clearing the path to performance and creating an environment in which employees do not feel restricted will be helpful. Finally, some employees may perceive little connection between their effort and performance level because they have an external locus of control, low self-esteem, or other personality traits that condition them to believe that their effort will not make a difference. In such cases, providing positive feedback and encouragement may help motivate employees.

Reinforcement Theory

Reinforcement theory is based on a simple idea that may be viewed as common sense. Beginning at infancy we learn through reinforcement. If you have observed a small child discovering the environment, you will see reinforcement theory in action. When the child discovers that twisting and turning a tap leads to water coming out and finds this outcome pleasant, he is more likely to repeat the behaviour. If he burns his hand while playing with hot water, the child is likely to stay away from the faucet in the future.

Despite the simplicity of reinforcement, how many times have you seen positive behaviour ignored, or worse, negative behaviour rewarded? In many organizations, this is a familiar scenario. People go above and beyond the call of duty, yet their actions are ignored or criticized. People with disruptive habits may receive no punishments because the manager is afraid of the reaction the person will give when confronted. Problem employees may even receive rewards such as promotions so they will be transferred to a different location and become someone else’s problem.

Reinforcement Interventions

How does a leader modify a team members’ behaviour so that the team member becomes more productive. ?

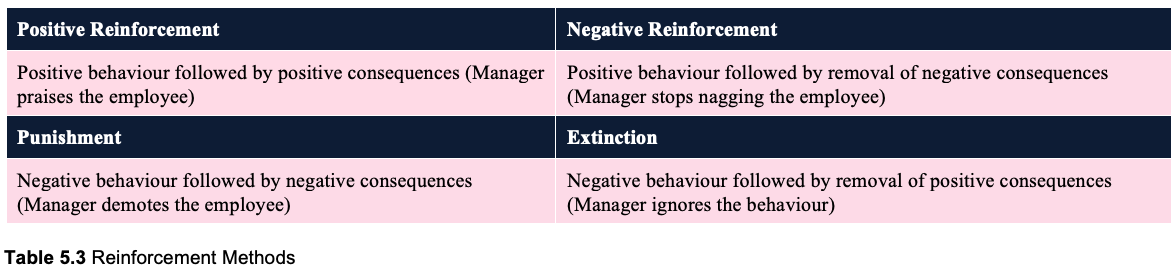

Reinforcement theory describes four interventions to modify employee behaviour. Two of these (Positive and Negative reinforcement) are methods of increasing the frequency of desired behaviours, while the remaining two (Punishment and Extinction) are methods of reducing the frequency of undesired behaviours.

Positive reinforcement is a method of increasing the desired behaviour (Beatty & Schneier, 1975). Positive reinforcement involves making sure that behaviour is met with positive consequences. For example, praising an employee for treating a customer respectfully is an example of positive reinforcement. If the praise immediately follows the positive behaviour, the employee will see a link between the behaviour and positive consequences and will be motivated to repeat similar behaviours.

Negative reinforcement is also used to increase the desired behaviour. Negative reinforcement involves removal of unpleasant outcomes once desired behaviour is demonstrated. Nagging an employee to complete a report is an example of negative reinforcement. The negative stimulus in the environment will remain present until positive behaviour is demonstrated. The problem with negative reinforcement is that the negative stimulus may lead to unexpected behaviours and may fail to stimulate the desired behaviour. For example, the person may start avoiding the manager to avoid being nagged.

Extinction is used to decrease the frequency of negative behaviours. Extinction is the removal of rewards following negative behaviour. Sometimes, negative behaviours are demonstrated because they are being inadvertently rewarded. For example, it has been shown that when people are rewarded for their unethical behaviours, they tend to demonstrate higher levels of unethical behaviours (Harvey & Sims, 1978). Thus, when the rewards following unwanted behaviours are removed, the frequency of future negative behaviours may be reduced. For example, if a co-worker is forwarding unsolicited e-mail messages containing jokes, commenting and laughing at these jokes may be encouraging the person to keep forwarding these messages. Completely ignoring such messages may reduce their frequency.

Punishment is another method of reducing the frequency of undesirable behaviours. Punishment involves presenting negative consequences following unwanted behaviours. Giving an employee a warning for consistently being late to work is an example of punishment.

An inspiring speech for your reflection

Jon Fisher (born January 19, 1972) is an entrepreneur, investor, author, speaker, philanthropist and inventor. Fisher is known for a viral commencement speech at the University of San Francisco. Here is an excerpt.

5.4 Motivation in Action: The Case of Trader Joe’s

People in Hawaiian T-shirts. Delicious fresh fruits and vegetables. A place where parking is tight and aisles are tiny. A place where you will be unable to find half the things on your list but will go home satisfied. We are, of course, talking about Trader Joe’s (a privately held company), a unique grocery store headquartered in California and located in 22 states. By selling store-brand and gourmet foods at affordable prices, this chain created a special niche for itself. Yet the helpful employees who stock the shelves and answer questions are definitely key to what makes this store unique and helps it achieve twice the sales of traditional supermarkets.

Shopping here is fun and chatting with employees is a routine part of this experience. Employees are upbeat and friendly to each other and to customers. If you look lost, there is the definite offer of help. But somehow the friendliness does not seem scripted. Instead, if they see you shopping for big trays of cheese, they might casually inquire if you are having a party and then point to other selections. If they see you chasing your toddler, they are quick to tie a balloon to his wrist. When you ask them if they have any cumin, they get down on their knees to check the back of the aisle, with the attitude of helping a guest that is visiting their home. How does a company make sure its employees look like they enjoy being there to help others?

One of the keys to this puzzle is pay. Trader Joe’s sells cheap organic food, but they are not “cheap” when it comes to paying their employees. Employees, including part-timers, are among the best paid in the retail industry. Full-time employees earn an average of $40,150 in their first year and also earn average annual bonuses of $950 with $6,300 in retirement contributions. Store managers’ average compensation is $132,000. With these generous benefits and above-market wages and salaries, the company has no difficulty attracting qualified candidates.

But money only partially explains what energizes Trader Joe’s employees. They work with people who are friendly and upbeat. The environment is collaborative, so that people fill in for each other and managers pick up the slack when the need arises, including tasks like sweeping the floors. Plus, the company promotes solely from within, making Trader Joe’s one of few places in the retail industry where employees can satisfy their career aspirations. Employees are evaluated every 3 months and receive feedback about their performance.

Employees are also given autonomy on the job. They can open a product to have the customers try it and can be honest about their feelings toward different products. They receive on- and off-the-job training and are intimately familiar with the products, which enables them to come up with ideas that are taken seriously by upper management. In short, employees love what they do, work with nice people who treat each other well, and are respected by the company. When employees are treated well, it is no wonder they treat their customers well daily (Lewis, 2005; McGregor et al., 2004; Speizer, 2004).

5.5 Conclusion

In this chapter, we have reviewed the basic motivation theories that have been developed to explain motivated behaviour. Several theories view motivated behaviour as attempts to satisfy needs. Based on this approach, managers would benefit from understanding what people need so that the actions of employees can be understood and managed. Other theories explain motivated behaviour using the cognitive processes of employees. Employees respond to unfairness in their environment, they learn from the consequences of their actions and repeat the behaviours that lead to positive results, and they are motivated to exert effort if they see their actions will lead to outcomes that would get them desired rewards. None of these theories are complete on their own, but each theory provides us with a framework we can use to analyze, interpret, and manage employee behaviours in the workplace.