Chapter 14: Organizational Culture

Chapter Learning outcomes

After reading this chapter, you should be able to know and learn the following:

- Describe organizational culture and why it is important for an organization.

- Understand the dimensions that make up a company’s culture.

- Distinguish between weak and strong cultures.

- Understand factors that create culture.

- Understand how to change culture.

- Understand how organizational culture and ethics relate.

- Understand cross-cultural differences in organizational culture.

- Understand the importance of embedding sustainability into culture

Introduction

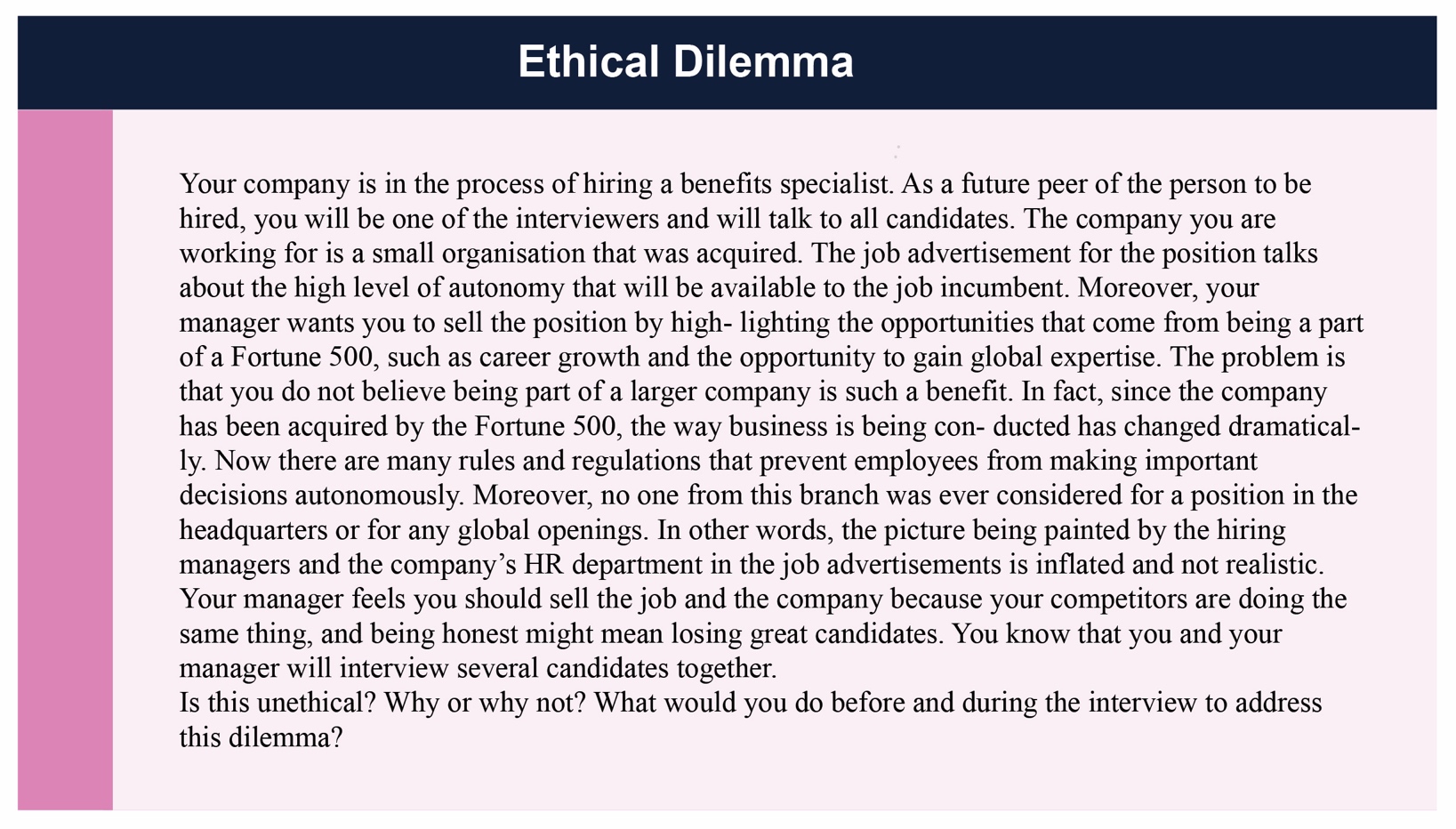

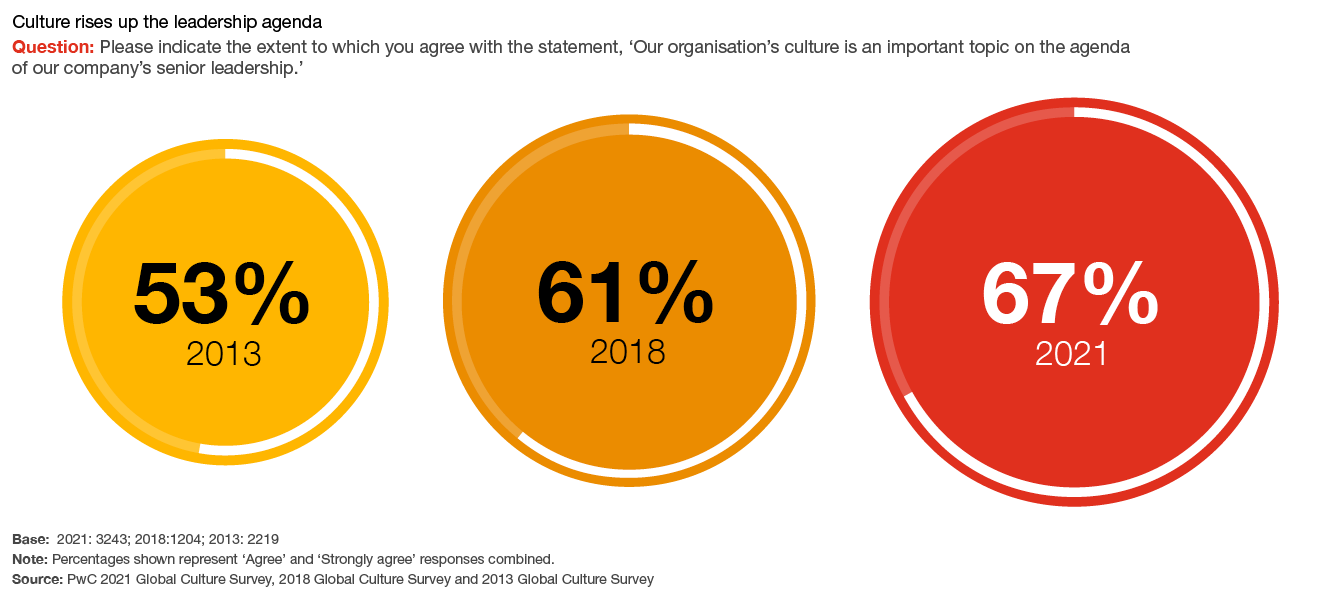

In a 2021 Global Culture Survey of 3,200 leaders and employees worldwide, PricewaterhouseCoopers, a leading, global consulting company highlighted the following findings:

- 67% of survey respondents said culture is more important than strategy or operations.

Just like individuals, you can think of organizations as having their own personalities, more typically known as organizational cultures. The opening case illustrates that Nordstrom is a retailer with the foremost value of making customers happy. At Nordstrom, when a customer is unhappy, employees are expected to identify what would make the person satisfied, and then act on it, without necessarily checking with a superior or consulting a lengthy policy book. If they do not, they receive peer pressure and may be made to feel that they let the company down. In other words, this organization seems to have successfully created a service culture. Understanding how culture is created, communicated, and changed will help you be more effective in your organizational life. But first, let’s define organizational culture.

14.1 Building a Customer Service Culture: The Case of Nordstrom

Nordstrom Inc. (NYSE: JWN) is a Seattle-based department store rivaling the likes of Saks Fifth Avenue, Neiman Marcus, and Bloomingdale’s. Nordstrom is a Hall of Fame member of Fortune magazine’s “100 Best Companies to Work For” list, including being ranked 34th in 2008. Nordstrom is known for its quality apparel, upscale environment, and generous employee rewards. However, what Nordstrom is most famous for is its delivery of customer service above and beyond the norms of the retail industry. Stories about Nordstrom service abound. For example, according to one story the company confirms, in 1975 Nordstrom moved into a new location that had formerly been a tire store. A customer brought a set of tires into the store to return them. Without a word about the mix-up, the tires were accepted, and the customer was fully refunded the purchase price. In a different story, a customer tried on several pairs of shoes but failed to find the right combination of size and color. As she was about to leave, the clerk called other Nordstrom stores but could only locate the right pair at Macy’s, a nearby competitor. The clerk had Macy’s ship the shoes to the customer’s home at Nordstrom’s expense. In a third story, a customer describes wandering into a Portland, Oregon, Nordstrom looking for an Armani tuxedo for his daughter’s wedding. The sales associate took his measurements just in case one was found. The next day, the customer got a phone call, informing him that the tux was available. When pressed, she revealed that using her connections she found one in New York, had it put on a truck destined to Chicago, and dispatched someone to meet the truck in Chicago at a rest stop. The next day she shipped the tux to the customer’s address, and the customer found that the tux had already been altered for his measurements and was ready to wear. What is even more impressive about this story is that Nordstrom does not sell Armani tuxedos.

How does Nordstrom persist in creating these stories? If you guessed that they have a large number of rules and regulations designed to emphasize quality in customer service, you’d be wrong. In fact, the company gives employees a 5½-inch by 7½-inch card as the employee handbook. On one side of the card, the company welcomes employees to Nordstrom and states that their number one goal is to provide outstanding customer service, and for this they have only one rule. On the other side of the card, the single rule is stated: “Use good judgment in all situations.” By leaving it in the hands of Nordstrom associates, the company seems to have empowered employees who deliver customer service heroics every day (Chatman & Eunyoung, 2003; McCarthy & Spector, 2005; Pfeffer, 2005).

14.2 Understanding Organizational Culture

What Is Organizational Culture?

Organizational culture refers to a system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that show employees what is appropriate and inappropriate behaviour (Chatman & Eunyoung, 2003; Kerr & Slocum Jr., 2005). These values have a strong influence on employee behaviour as well as organizational performance. In fact, the term organizational culture was made popular in the 1980s when Peters and Waterman’s best-selling book In Search of Excellence made the argument that company success could be attributed to an organizational culture that was decisive, customer oriented, empowering, and people oriented. Since then, organizational culture has become the subject of numerous research studies, books, and articles. However, organizational culture is still a relatively new concept. In contrast to a topic such as leadership, which has a history spanning several centuries, organizational culture is a young but fast-growing area within organizational behaviour.

Culture is by and large invisible to individuals. Even though it affects all employee behaviours, thinking, and behavioural patterns, individuals tend to become more aware of their organization’s culture when they have the opportunity to compare it to other organizations. If you have worked in multiple organizations, you can attest to this. Maybe the first organization you worked at was a place where employees dressed formally. It was completely inappropriate to question your boss in a meeting; such behaviours would only be acceptable in private. It was important to check your e-mail at night as well as during weekends or else you would face questions on Monday about where you were and whether you were sick. Contrast this company to a second organization where employees dress more casually. You are encouraged to raise issues and question to your boss or peers, even in front of clients. What is more important is not to maintain impressions but to arrive at the best solution to any problem. It is widely known that family life is very important, so it is acceptable to leave work a bit early to go to a family event. Additionally, you are not expected to do work at night or over the weekends unless there is a deadline. These two hypothetical organizations illustrate that organizations have different cultures, and culture dictates what is right and what is acceptable behaviour as well as what is wrong and unacceptable.

Why Does Organizational Culture Matter?

Some key questions you will ask yourself as you embark upon and over your career are:

“What should I do to get ahead in my organization? What makes people successful here? What will make me successful?”

Charles O’Reilly, co-director of the Stanford Graduate School of Business, posed that question and invited VMware’s (an American cloud computing) employees to reflect on what the company rewarded.

Employees started filling the board with the usual suspects—innovate, work hard, be open, and be collaborative. But with prompting, more specific behaviors started to appear: “Be available on email 24×7,” “Sound smart,” and “Get consensus on your decisions.” Once the team had finished, Professor O’Reilly pointed at the whiteboard and said, “That’s your culture. Your culture is the behaviors you reward and punish.”

The discussion about the behaviors that are rewarded and punished is much harder than it seems and leaders often struggle with this exercise. Listing values is easy; connecting them to actual behaviors is a different story.

Research indicates that stated values often don’t have a significant impact and can even have a negative effect. An MIT Sloan study found no correlation between a company’s expressed values and how employees felt they lived up to them. For example, promoting diversity but not supporting it with action can do more harm than good. Statements such as “We don’t discriminate” create an impression that the organization has achieved equity and fairness when, in fact, it hasn’t.

Behavioral cues, on the other hand, provide concrete guidance on how to translate values into actions. Leaders must clarify why they matter. According to the same study by MIT, less than one-quarter of companies connect values with behaviors, and a significant majority fail to link beliefs with business success.

You can’t call your culture “transparent” if people are afraid of speaking truth to power. You can’t say you have a “collaborative” workplace if you regularly promote selfish employees. You can’t pronounce your culture “innovative” if breakthrough ideas are often killed before they see the light of day.

An organization’s culture may be one of its strongest assets, as well as its biggest liability. In fact, it has been argued that organizations that have a rare and hard-to-imitate organizational culture benefit from it as a competitive advantage (Barney, 1986). In a survey conducted by the management consulting firm Bain & Company in 2007, worldwide business leaders identified corporate culture as important as corporate strategy for business success (Why culture can mean life or death, 2007). This comes as no surprise to many leaders of successful businesses, who are quick to attribute their company’s success to their organization’s culture.

Culture, or shared values within the organization, may be related to increased performance. Researchers found a relationship between organizational cultures and company performance, with respect to success indicators such as revenues, sales volume, market share, and stock prices (Kotter & Heskett, 1992; Marcoulides & Heck, 1993). At the same time, it is important to have a culture that fits with the demands of the company’s environment. To the extent shared values are proper for the company in question, company performance may benefit from culture (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987). For example, if a company is in the high-tech industry, having a culture that encourages innovativeness and adaptability will support its performance. However, if a company in the same industry has a culture characterized by stability, a high respect for tradition, and a strong preference for upholding rules and procedures, the company may suffer as a result of its culture. In other words, just as having the “right” culture may be a competitive advantage for an organization, having the “wrong” culture may lead to performance difficulties, may be responsible for organizational failure, and may act as a barrier preventing the company from changing and taking risks.

In addition to having implications for organizational performance, organizational culture can dictate employee behaviour. Culture is in fact a more powerful way of controlling and managing employee behaviours than organizational rules and regulations. When problems are unique, rules tend to be less helpful. Instead, creating a culture of customer service achieves the same result by encouraging employees to think like customers, knowing that the company priorities in this case are clear: keeping the customer happy is preferable to other concerns such as saving the cost of a refund.

Levels of Organizational Culture

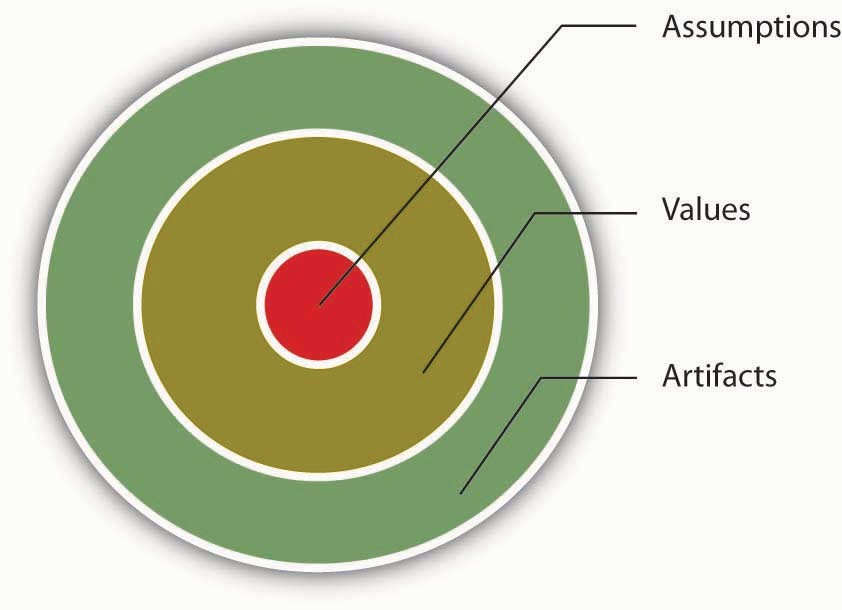

Organizational culture consists of some aspects that are relatively more visible, as well as aspects that may lie below one’s conscious awareness. Organizational culture can be thought of as consisting of three interrelated levels (Schein, 1992).

At the deepest level, below our awareness lie basic assumptions. Assumptions are taken for granted, and they reflect beliefs about human nature and reality. Organizational assumptions are usually “known,” but are not discussed, nor are they written or easily found. They are comprised of unconscious thoughts, beliefs, perceptions, and feelings (Schein, 2004).

“This will be difficult!”

In some cultures, like the US, this can mean “Yes, we can do that!”

In others, like Japan, this can mean, “No, it’s not possible.”

These are examples of cultural assumptions that often creep into our daily lives.

At the second level, values exist. Values are shared principles, standards, and goals. Values are officially introduced in a company’s mission, vision, and values statements.

HubSpot (an American developer and marketer of software products) has about 73,400 customers and more than 3,800 employees in the company as at February 2022 and have more than $674 million in annual revenue. HubSpot culture is driven by a shared passion for our mission and metrics. It is a culture of amazing, growth-minded people whose values include using good judgment and solving for the customer. Employees who work at HubSpot have HEART: Humble, Empathetic, Adaptable, Remarkable, Transparent. These are HubSpot’s key values.

Finally, at the surface we have artifacts, or visible, tangible aspects of organizational culture. For example, in an organization, one of the basic assumptions employees and managers share might be that happy employees benefit their organizations. This assumption could translate into values such as social equality, high quality relationships, and having fun. The artifacts reflecting such values might be an executive “open door” policy, an office layout that includes open spaces and gathering areas equipped with pool tables, and frequent company picnics in the workplace. For example, Alcoa Inc. designed their headquarters to reflect the values of making people more visible and accessible, and to promote collaboration (Stegmeier, 2008). In other words, understanding the organization’s culture may start from observing its artifacts: the physical environment, employee interactions, company policies, reward systems, and other observable characteristics.

When you are interviewing for a position, observing the physical environment, how people dress, where they relax, and how they talk to others is definitely a good start to understanding the company’s culture. However, simply looking at these tangible aspects is unlikely to give a full picture of the organization. An important chunk of what makes up culture exists below one’s degree of awareness. The values and, at a deeper level, the assumptions that shape the organization’s culture can be uncovered by observing how employees interact and the choices they make, as well as by inquiring about their beliefs and perceptions regarding what is right and appropriate behaviour.

These are examples of how leading brands link values to behaviours and thereby enable a productive, performance driven, culture:

Amazon punishes “complacency” and having a “Day 2 mentality.” Mediocrity is not welcomed. The tech giant rewards speed, relentlessness, and intellectual autonomy. This is consistent with Amazon’s aggressive culture.

HubSpot punishes taking shortcuts to achieve short-term results. Conversely, it rewards simplicity, being a “culture-add” (someone who actively improves the company), work and life balance, and results delivered, not hours worked.

Slack (an instant messaging program) punishes “brilliant jerks.” There’s no room for people who are disrespectful or not team players. Instead, Slack rewards empathy, a characteristic that’s crucial to getting a job at the tech company.

14.3 Characteristics of Organizational Culture

Dimensions of Culture

Which values characterize an organization’s culture? Even though culture may not be immediately observable, identifying a set of values that might be used to describe an organization’s culture helps us identify, measure, and manage culture more effectively. For this purpose, several researchers have proposed various culture typologies. One typology that has received a lot of research attention is the organizational culture profile (OCP), in which culture is represented by seven distinct values (Chatman & Jehn, 1991; O’Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell, 1991). We will describe the OCP as well as two additional dimensions of organizational culture that are not represented in that framework but are important dimensions to consider: service culture and safety culture.

Innovative Cultures

According to the OCP framework, companies that have innovative cultures are flexible and adaptable, and experiment with new ideas. These companies are characterized by a flat hierarchy in which titles and other status distinctions tend to be downplayed.

W. L. Gore & Associates has made its name by creating innovative, technology-driven solutions, from medical devices that treat aneurysms to high-performance GORE‑TEX fabrics. A privately held company whose annual sales exceed $2.5 billion, Gore is committed to perpetuating its more than 50-year tradition of product innovation. Gore focuses its efforts in four main areas: electronics, fabrics, industrial and medical products. Gore’s fabrics provide protection from the elements and enable wearers to remain comfortable across a broad range of activities and conditions.

Gore is as well known for its unique corporate culture as it is for its innovative products. The company uses a team-based environment that encourages personal initiative and person-to-person communication among all “associates,” as employees are known. Gore’s emphasis on minimal barriers to creativity and sound decision making has proved to be good business. The company has earned a reputation for integrity and ethical practices, a reputation reinforced by its unwavering commitment to product performance and reliability. By encouraging individual initiative and innovation, the corporate culture fosters both product success and associate satisfaction. Today Gore is one of only four companies to appear in every listing of the “100 Best Companies to Work for in America,” now published annually in Fortune magazine. The company also ranks consistently among the “Best Companies to Work For” in the U.K., Germany, Italy and France.

Aggressive Cultures

In an article of the New York Times dated February 22, 2017, it was written that when new employees join Uber, they are asked to subscribe to 14 core company values, including making bold bets, being “obsessed” with the customer, and “always be hustlin’.” The ride-hailing service particularly emphasizes “meritocracy,” the idea that the best and brightest will rise to the top based on their efforts, even if it means stepping on toes to get there.

Those values have helped propel Uber to one of Silicon Valley’s biggest success stories.

Yet the focus on pushing for the best result has also fueled what current and former Uber employees describe as an environment in which workers are sometimes pitted against one another and where a blind eye is turned to infractions from top performers.

Interviews with more than 30 current and former Uber employees, as well as reviews of internal emails, chat logs and tape-recorded meetings, paint a picture of an often unrestrained workplace culture. Among the most egregious accusations from employees, who either witnessed or were subject to incidents and who asked to remain anonymous because of confidentiality agreements and fear of retaliation: One Uber manager groped female co-workers’ breasts at a company retreat in Las Vegas. A director shouted a homophobic slur at a subordinate during a heated confrontation in a meeting. Another manager threatened to beat an underperforming employee’s head in with a baseball bat.

Susan Fowler, an engineer who left Uber in December 2016, published a blog post about her time at the company. She detailed a history of discrimination and sexual harassment by her managers, which she said was shrugged off by Uber’s human resources department. Ms. Fowler said the culture was stoked — and even fostered — by those at the top of the company.

“It seemed like every manager was fighting their peers and attempting to undermine their direct supervisor so that they could have their direct supervisor’s job,” Ms. Fowler wrote. “No attempts were made by these managers to hide what they were doing: They boasted about it in meetings, told their direct reports about it, and the like.”

Outcome-Oriented Cultures

The OCP framework describes outcome-oriented cultures as those that emphasize achievement, results, and action as important values. A good example of an outcome-oriented culture may be Best Buy Co. Inc.

Best Buy (BB) is continually redefining the norms of how their business operates. Here is one such example of tech innovation during the pandemic

At the beginning of the pandemic, it was incredibly important for BB to quickly understand how their customers’ needs for technology were changing, especially as people across the country had to immediately begin working and learning from home. BB also needed to quickly figure out how to engage with them safely and reliably, in an uncertain and rapidly changing environment.

Within just a couple of days BB implemented new technology that allowed their stores to continue supporting their customers’ essential tech needs in the safest ways possible, both for them and for their employees. That included offering contactless curbside pickup and the ability for store employees to conduct virtual consultations with customers. BB also quickly built out capabilities within our employee app that allowed for COVID-19 health screenings prior to employees’ shifts.

BB has leant how crucial it is for them to quickly adapt to their customer’s pressing technology needs, and have shifted to a “digital-first” mindset. Their teams are helping the company figure out where they can leverage tech and data science, so BB can quickly create breakthrough experiences, enable better ways to help customers and speed up how they test, learn and solve complex problems.

Outcome-oriented cultures hold employees as well as managers accountable for success and utilize systems that reward employee and group output. In these companies, it is more common to see rewards tied to performance indicators as opposed to seniority or loyalty. Research indicates that organizations that have a performance-oriented culture tend to outperform companies that are lacking such a culture (Nohria, Joyce, & Roberson, 2003). At the same time, some outcome-oriented companies may have such a high drive for outcomes and measurable performance objectives that they may suffer negative consequences. Companies over-rewarding employee performance such as Enron Corporation and WorldCom experienced well-publicized business and ethical failures. When performance pressures lead to a culture where unethical behaviours become the norm, individuals see their peers as rivals and short-term results are rewarded; the resulting unhealthy work environment serves as a liability (Probst & Raisch, 2005).

Stable Cultures

Stable cultures are predictable, rule-oriented, and bureaucratic. These organizations aim to coordinate and align individual effort for greatest levels of efficiency. When the environment is stable and certain, these cultures may help the organization be effective by providing stable and constant levels of output (Westrum, 2004). These cultures prevent quick action, and as a result may be a misfit to a changing and dynamic environment. Public sector institutions may be viewed as stable cultures. In the private sector, Kraft Foods Inc. is an example of a company with centralized decision making and rule orientation that suffered as a result of the culture-environment mismatch (Thompson, 2006). Its bureaucratic culture is blamed for killing good ideas in early stages and preventing the company from innovating. When the company started a change program to increase the agility of its culture, one of their first actions was to fight bureaucracy with more bureaucracy: they created the new position of VP of business process simplification, which was later eliminated (Boyle, 2004; Thompson, 2005; Thompson, 2006).

People-Oriented Cultures

People-oriented cultures value fairness, supportiveness, and respect for individual rights. These organizations truly live the mantra that “people are their greatest asset.” In addition to having fair procedures and management styles, these companies create an atmosphere where work is fun and employees do not feel required to choose between work and other aspects of their lives. In these organizations, there is a greater emphasis on and expectation of treating people with respect and dignity (Erdogan, Liden, & Kraimer, 2006). One study of new employees in accounting companies found that employees, on average, stayed 14 months longer in companies with people-oriented cultures (Sheridan, 1992).

Southwest Airlines’ culture is woven into all aspects of the company, from business performance to employee happiness. The airline puts employees first; this tribal type of company culture promotes strong relationships among colleagues.

Three crucial elements define Southwest Airlines’ company culture: appreciation, recognition, and celebration.

A decade or so ago, the company decided to formalize its workplace culture by identifying six core values and creating a Culture Services department.

Southwest Airlines has many rituals to bring its values to life and celebrate each other. One of the most significant is “Culture Blitzes” in which a team visits an airport, touching every Southwest employee with food, fun, and support. The team even cleans the planes, allowing the crew to leave as soon as they land.

The company’s logo is a heart and employees believe that ” without a heart, the plane is just a machine”.

Team-Oriented Cultures

Companies with team-oriented cultures are collaborative and emphasize cooperation among employees.

Slack’s company culture is a vivid metaphor of its own product. The company acts as an excellent collaboration hub, embracing an open by default communication approach. Rather than choose specific channels, Slack’s CEO wants communications to be transparent, so everyone knows what’s going on and are able to provide solutions.

At Slack, people work hard and go home. The company culture understands that people have lives – they expect high performance and total dedication, but only during regular working hours. Funnily enough, employees are forbidden to use the Slack app after 6 pm or during the weekend.

The power of words plays a crucial role in Slack culture. Employees are encouraged to speak well and with purpose. There’s an obsession with continually improving communication – both their own and their clients’.

A strong sense of community is essential to Slack’s powerful company culture. Empathy is vital to not only understanding the end user, but also their colleagues. Slack promotes diversity and recruits people with diverse backgrounds and voices. Everyone has an obligation to contribute and make things better.

Detail-Oriented Cultures

Organizations with detail-oriented cultures are characterized in the OCP framework as emphasizing precision and paying attention to details. Such a culture gives a competitive advantage to companies in the hospitality industry by helping them differentiate themselves from others.

How much would you empower your employees to serve your customers? The Ritz-Carlton has put a number to that very question.

The Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, LLC is an American multinational company that operates the luxury hotel chain known as The Ritz-Carlton. The company has 108 luxury hotels and resorts in 30 countries and territories with 29,158 rooms,

If you’re one of their customers, the good news is that…The Ritz-Carlton Will Spend $2,000 To Make You Happy. The Ritz empowers its employees to spend up to $2,000 to solve customer problems without asking for a manager.

The real point of the $2000 of discretion, as Ritz-Carlton president and COO Herve Humler explains, is as a tool to empower and encourage employees to use their time, effort and –when needed–the company’s money to enhance the experience of any guest– even a guest who is already having a blast! It’s an approach that’s not just about solving problems but about finding opportunities.

The hotel keeps records of all customer requests, such as which newspaper the guest prefers or what type of pillow the customer uses. This information is put into a computer system and used to provide better service to returning customers. Any requests hotel employees receive, as well as overhear, might be entered into the database to serve customers better. The hotel knows that in the long run they will be rewarded with loyalty and that the customer relationship they will preserve is worth far more than any individual transaction.

Service Culture

Service culture is not one of the dimensions of OCP, but given the importance of the retail industry in the overall economy, having a service culture can make or break an organization. Some of the organizations we have illustrated in this section, such as Nordstrom, Southwest Airlines and the Ritz-Carlton are famous for their service culture. In these organizations, employees are trained to serve the customer well, and cross-training is the norm. Employees are empowered to resolve customer problems in ways they see fit. Because employees with direct customer contact are in the best position to resolve any issues, employee empowerment is truly valued in these companies. For example, Umpqua Bank, operating in the northwestern United States, is known for its service culture. All employees are trained in all tasks to enable any employee to help customers when needed. Branch employees may come up with unique ways in which they serve customers better, such as opening their lobby for community events or keeping bowls full of water for customers’ pets. The branches feature coffee for customers, Internet kiosks, and withdrawn funds are given on a tray along with a piece of chocolate. They also reward employee service performance through bonuses and incentives (Conley, 2005; Kuehner-Herbert, 2003).

Safety Culture

Simply put, an organization’s workplace safety culture (sometimes called “safety climate”) describes the values, priorities, beliefs, and ideals individual members of that organization express relating to staying safe, as well as how those ideas propagate throughout the organization.

In organizations where safety-sensitive jobs are performed, creating and maintaining a safety culture provides a competitive advantage because the organization can reduce accidents, maintain high levels of morale and employee retention, and increase profitability by cutting workers’ compensation insurance costs.

Mark French, Dalkia Energy Solutions, says: “Dalkia uses the term “zero harm” to describe their safety efforts. It is a wonderful phrase that sums up what I feel my goal is as a safety professional. The real mission is to prevent any harm to my team, to the environment, and to the clients and communities that we service. Dalkia has a distinct focus on culture, not just on safety. It is a culture that is focused on people which means empowerment, inclusion, and a safe place to work.”

Matt McMahan, Texas Roadhouse, emphasizes the importance of adapting to the given situation: “The meaning of safety culture will differ depending on the circumstances. When referring to operational safety, it can mean daily awareness and frequent communication. In terms of safety management, the signs of a safety culture can mean the attention around identifying and determining appropriate treatment for the identified risks.”

Some companies suffer severe consequences when they are unable to develop such a culture.

Strength of Culture

A strong culture is one that is shared by organizational members (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987; Chatman & Eunyoung, 2003). In other words, if most employees in the organization show consensus regarding the values of the company, it is possible to talk about the existence of a strong culture. A culture’s content is more likely to affect the way employees think and behave when the culture in question is strong. For example, cultural values emphasizing customer service will lead to higher quality customer service if there is widespread agreement among employees on the importance of customer service related values (Schneider, Salvaggio, & Subirats, 2002).

Building a strong, agile company culture has contributed to Spotify’s rapid growth. Its experiment-friendly culture with an emphasis on test-and-learn and mistake-tolerance has become the paradigm for many to follow.

One of the clues lies in balancing employee autonomy and accountability. Spotify’s approach starts by aligning employees around one shared purpose and allowing teams to discover their own way to get there. This requires providing freedom for experimentation, balancing alignment with control, and autonomous team structures that are fully accountable..

At Spotify, flexibility is not about what people want, but about being more mindful of their choices. For example, take the “pull the plug” norm. While executives in most companies keep pushing projects even if they lack traction, Spotify employees are data-informed – when they don’t see the expected results, people can pull the plug.

Spotify employees are encouraged to break the rules with a purpose. If something works, they keep it; otherwise, they dump it. Context matters too. Spotify culture works under the premise that “What works well in most places, may not work in your environment.”

It is important to realize that a strong culture may act as an asset or liability for the organization, depending on the types of values that are shared. For example, imagine a company with a culture that is strongly outcome oriented. If this value system matches the organizational environment, the company outperforms its competitors. On the other hand, a strong outcome-oriented culture coupled with unethical behaviours and an obsession with quantitative performance indicators may be detrimental to an organization’s effectiveness. An extreme example of this dysfunctional type of strong culture is Enron.

A strong culture may sometimes outperform a weak culture because of the consistency of expectations. In a strong culture, members know what is expected of them, and the culture serves as an effective control mechanism on member behaviours. Research shows that strong cultures lead to more stable corporate performance in stable environments. However, in volatile environments, the advantages of culture strength disappear (Sorensen, 2002).

One limitation of a strong culture is the difficulty of changing a strong culture. If an organization with widely shared beliefs decides to adopt a different set of values, unlearning the old values and learning the new ones will be a challenge, because employees will need to adopt new ways of thinking, behaving, and responding to critical events. For example, the Home Depot Inc. had a decentralized, autonomous culture where many business decisions were made using “gut feeling” while ignoring the available data. When Robert Nardelli became CEO of the company in 2000, he decided to change its culture, starting with centralizing many of the decisions that were previously left to individual stores. This initiative met with substantial resistance, and many high-level employees left during his first year. Despite getting financial results such as doubling the sales of the company, many of the changes he made were criticized. He left the company in January 2007 (Charan, 2006; Herman & Wernle, 2007).

A strong culture may also be a liability during a merger. During mergers and acquisitions, companies inevitably experience a clash of cultures, as well as a clash of structures and operating systems. Culture clash becomes more problematic if both parties have unique and strong cultures.

Do Organizations Have a Single Culture?

So far, we have assumed that a company has a single dominant culture that is shared throughout the organization. However, you may have realized that this is an oversimplification. In reality there might be multiple cultures within any given organization. For example, people working on the sales floor may experience a different culture from that experienced by people working in the warehouse. The Marketing team formed by extrovert personalities represent a different subculture from those in Finance or Accounting teams. A culture that emerges within different departments, branches, or geographic locations is called a subculture. Subcultures may arise from the personal characteristics of employees and managers, as well as the different conditions under which work is performed.

A subculture can function quite well within the dominant culture.

Counterculture groups are also smaller groups of like-minded people who gather within a more dominant culture. However, different from a subculture, a countercultural group goes against the mainstream dominant culture. In fact, the key difference between a counterculture movement and subculture is the strong desire to change the dominant culture. These groups are created to fight against the pervasive values of a larger culture. They are formed around interests, dislikes, and disdain. Google’s employees formed a counterculture to resist participating in the making of drones for the United States armed forces. They said that it goes against the company’s values of “Don’t be evil”

14.4 Creating and Maintaining Organizational Culture

How Are Cultures Created?

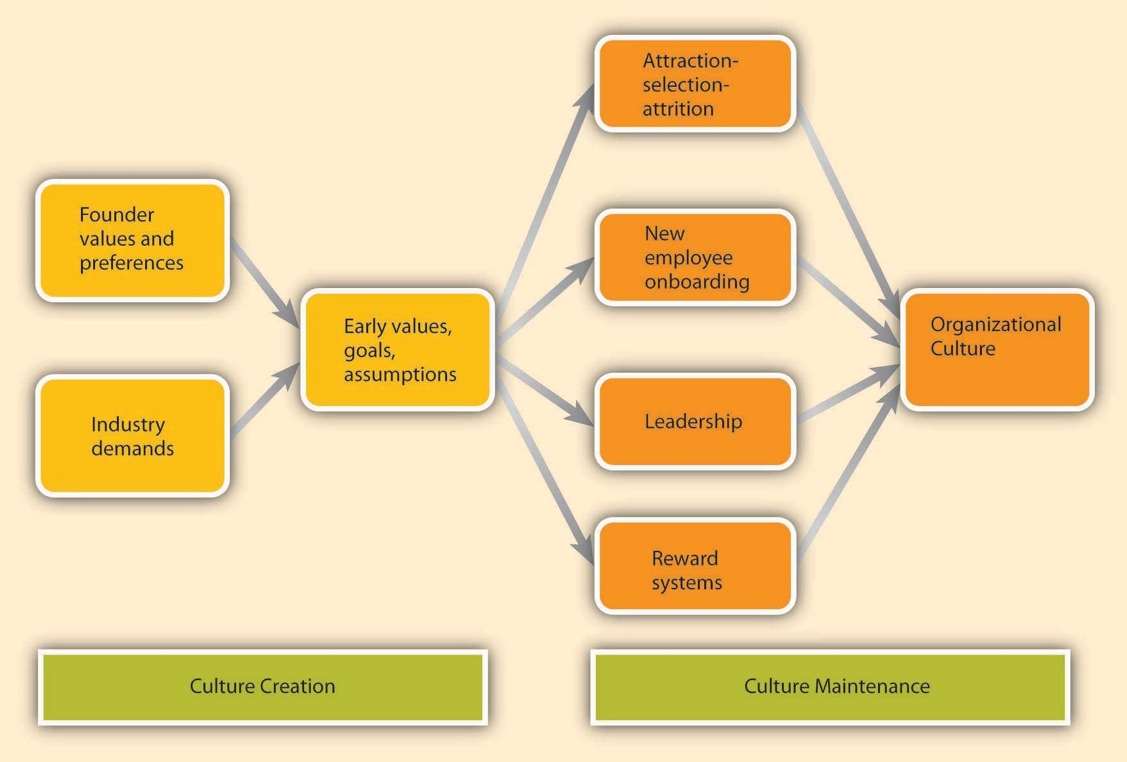

Where do cultures come from? Understanding this question is important so that you know how they can be changed. An organization’s culture is shaped as the organization faces external and internal challenges and learns how to deal with them. When the organization’s way of doing business provides a successful adaptation to environmental challenges and ensures success, those values are retained. These values and ways of doing business are taught to new members as the way to do business (Schein, 1992). The factors that are most important in the creation of an organization’s culture include founders’ values, preferences, and industry demands.

Founder’s Values

A company’s culture, particularly during its early years, is inevitably tied to the personality, background, and values of its founder or founders, as well as their vision for the future of the organization. This explains one reason why culture is so hard to change: It is shaped in the early days of a company’s history. When entrepreneurs establish their own businesses, the way they want to do business determines the organization’s rules, the structure set-up in the company, and the people they hire to work with them.

As a case in point, some of the existing corporate values of the ice cream company Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Holdings Inc. can easily be traced to the personalities of its founders Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield. In 1978, the two ex-hippie high school friends opened up their first ice-cream shop in a renovated gas station in Burlington, Vermont. Their strong social convictions led them to buy only from the local farmers and devote a certain percentage of their profits to charities. The core values they instilled in their business can still be observed in the current company’s devotion to social activism and sustainability: continuous contributions to charities, use of environmentally friendly materials, and dedication to creating jobs in low-income areas.

In 2021 , Ben & Jerry made decision to stop selling its ice cream in the Israeli occupied West Bank. The company said sales in the territories are “inconsistent with our values”, adding that the move reflected the concerns of “fans and trusted partners”.

In 2020, the ice cream brand unveiled a new flavour which takes aim at the Australian government’s use of fossil fuels. The tub for the Unfudge Our Future flavour — a mix of “chocolate and peanut butter non-dairy ice cream, fudge brownies and peanut butter cookie dough” — features the message: “Dear Scott Morrison, make fossil fuels history!”

In 2020, the company sparked debate across social media after it launched a scathing attack on the U.K. Government’s treatment of migrants. It wrote: “People wouldn’t make dangerous journeys if they had any other choice. The UK hasn’t resettled any refugees since March, but wars and violence continue. What we need is more safe and legal routes.”

Industry Demands

While founders undoubtedly exert a powerful influence over corporate cultures, the industry characteristics also play a role. Industry characteristics and demands act as a force to create similarities among organizational cultures. For example, despite some differences, many companies in the insurance and banking industries are stable and rule oriented, many companies in the high-tech industry have innovative cultures, and companies in the non-profit industry tend to be people oriented. If the industry is one with a large number of regulatory requirements—for example, banking, health care, and nuclear power plant industries—then we might expect the presence of a large number of rules and regulations, a bureaucratic company structure, and a stable culture. Similarly, the high-tech industry requires agility, taking quick action, and low concern for rules and authority, which may create a relatively more innovative culture (Chatman & Jehn, 1994; Gordon, 1991). The industry influence over culture is also important to know, because this shows that it may not be possible to imitate the culture of a company in a different industry, even though it may seem admirable to outsiders.

How Are Cultures Maintained?

As a company matures, its cultural values are refined and strengthened. The early values of a company’s culture exert influence over its future values. It is possible to think of organizational culture as an organism that protects itself from external forces. Organizational culture determines what types of people are hired by an organization and what types are left out. Moreover, once new employees are hired, the company assimilates new employees and teaches them the way things are done in the organization. We call these processes attraction-selection-attrition and onboarding processes. We will also examine the role of leaders and reward systems in shaping and maintaining an organization’s culture. It is important to remember two points: the process of culture creation is in fact more complex and less clean than the name implies. Additionally, the influence of each factor on culture creation is reciprocal. For example, just as leaders may influence what type of values the company has, the culture may also determine what types of behaviours leaders demonstrate.

Attraction-Selection-Attrition (ASA)

Organizational culture is maintained through a process known as attraction-selection-attrition.

First, employees are attracted to organizations where they will fit in. In other words, different job applicants will find different cultures to be attractive. Someone who has a competitive nature may feel comfortable and prefer to work in a company where interpersonal competition is the norm. Others may prefer to work in a team-oriented workplace. Research shows that employees with different personality traits find different cultures attractive. For example, out of the Big Five personality traits, employees who demonstrate neurotic personalities were less likely to be attracted to innovative cultures, whereas those who had openness to experience were more likely to be attracted to innovative cultures (Judge & Cable, 1997). As a result, individuals will self-select the companies they work for and may stay away from companies that have core values that are radically different from their own.

Of course, this process is imperfect and value similarity is only one reason a candidate might be attracted to a company. There may be other, more powerful attractions such as good benefits. For example, candidates who are potential misfits may still be attracted to Google because of the cool perks associated with being a Google employee.

At this point in the process, the second component of the ASA framework prevents them from getting in: Selection. Just as candidates are looking for places where they will fit in, companies are also looking for people who will fit into their current corporate culture. Many companies are hiring people for fit with their culture, as opposed to fit with a certain job. For example, Southwest Airlines prides itself for hiring employees based on personality and attitude rather than specific job-related skills, which are learned after being hired. This is important for job applicants to know, because in addition to highlighting your job-relevant skills, you will need to discuss why your personality and values match those of the company. Companies use different techniques to weed out candidates who do not fit with corporate values. For example, Google relies on multiple interviews with future peers. By introducing the candidate to several future coworkers and learning what these coworkers think of the candidate, it becomes easier to assess the level of fit. The Container Store Inc. ensures culture fit by hiring among their customers (Arnold, 2007). This way, they can make sure that job candidates are already interested in organizing their lives and understand the company’s commitment to helping customers organize theirs. Companies may also use employee referrals in their recruitment process. By using their current employees as a source of future employees, companies may make sure that the newly hired employees go through a screening process to avoid potential person-culture mismatch.

Even after a company selects people for person-organization fit, there may be new employees who do not fit in. Some candidates may be skillful in impressing recruiters and signal high levels of culture fit even though they do not necessarily share the company’s values. Moreover, recruiters may suffer from perceptual biases and hire some candidates thinking that they fit with the culture even though the actual fit is low. In any event, the organization is going to eventually eliminate candidates who do not fit in through attrition. Attrition refers to the natural process in which the candidates who do not fit in will leave the company. Research indicates that person-organization misfit is one of the important reasons for employee turnover (Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005; O’Reilly III, Chatman, & Caldwell, 1991).

New Employee Onboarding

Another way in which an organization’s values, norms, and behavioural patterns are transmitted to employees is through onboarding (also referred to as the organizational socialization process). Onboarding refers to the process through which new employees learn the attitudes, knowledge, skills, and behaviours required to function effectively within an organization. If an organization can successfully socialize new employees into becoming organizational insiders, new employees feel confident regarding their ability to perform, sense that they will feel accepted by their peers, and understand and share the assumptions, norms, and values that are part of the organization’s culture. This understanding and confidence in turn translate into more effective new employees who perform better and have higher job satisfaction, stronger organizational commitment, and longer tenure within the company (Bauer et al., 2007).

Netflix aims to set employees up for success from day one. The company adopts a “welcome home” approach, ensuring employees feel secure and grounded stepping into a new workplace.

“There is a general trust between managers and employees, with a big focus on feedback.” Glassdoor comment.

Following this approach, Netflix prepares all new hire necessities—such as office space, equipment and documents—for a smooth transition. New employee initiations start with an orientation process that is primarily ongoing for the first quarter of the employee’s first year.

Orientation covers company culture and vision, with insights spread out at different intervals throughout the employee’s learning process. During the onboarding period, managers ensure to schedule periodic introductions with different teams. What really stands out about Netflix’s onboarding program is the extraordinary amount of trust the company places in its new hires’ expertise. From the very first day, they are assigned important projects which they are expected to start working on immediately. By making them a significant player in the decision-making process from the get-go, Netflix empowers its new hires with a sense of authority.

“The managers are always ready to help.” Glassdoor comment

Managers also assign mentors to each new employee for additional guidance. In order to make their roles and the onboarding process feel engaging from day one, new employees are assigned key projects and tasks from the start. This ensures high engagement levels and a positive first impression which can have lasting effects, as the new employee feels immediately of added value.

“The job training course is excellent. ” Glassdoor comment

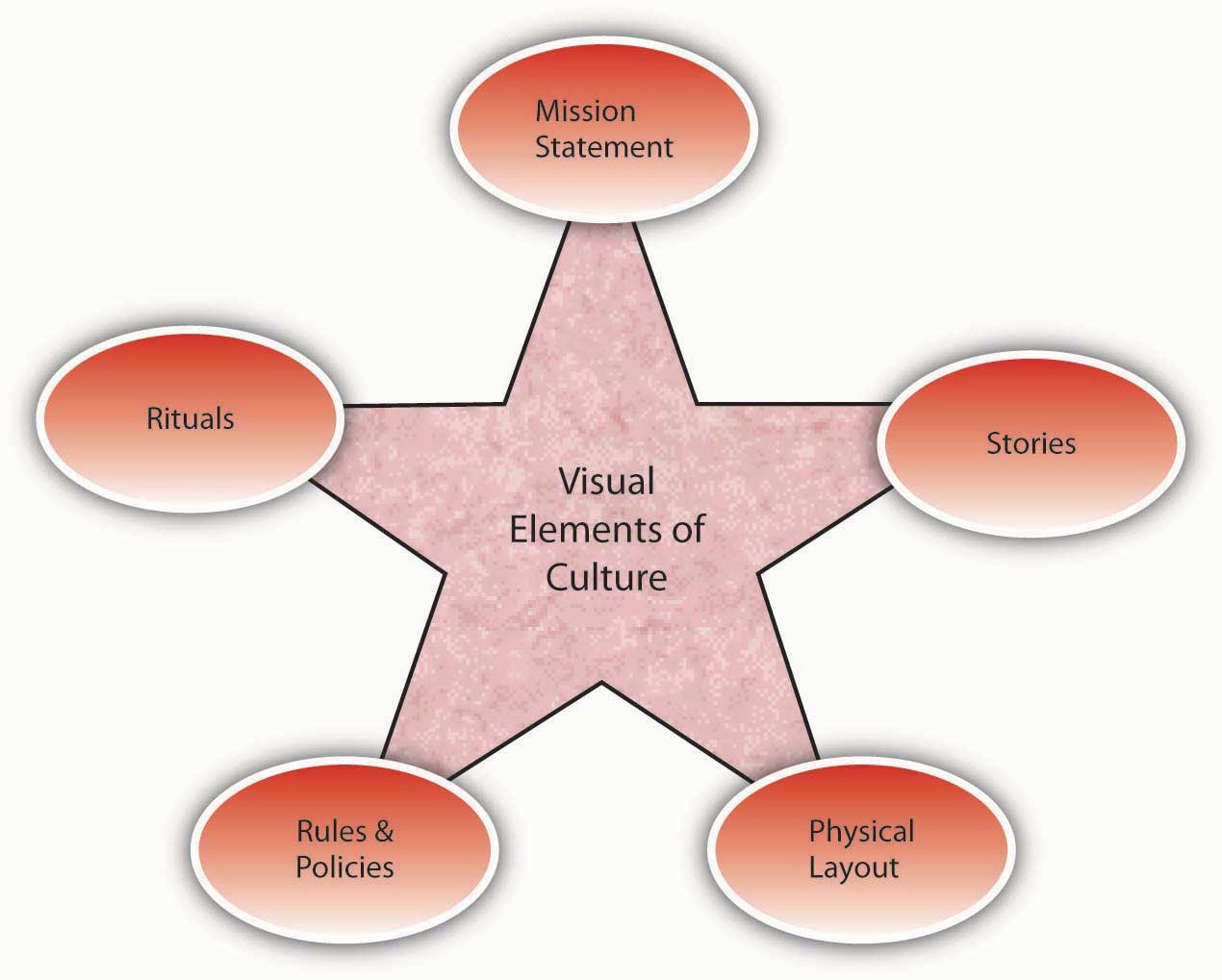

Visual Elements of Organizational Culture

How do you find out about a company’s culture? We emphasized earlier that culture influences the way members of the organization think, behave, and interact with one another. Thus, one way of finding out about a company’s culture is by observing employees or interviewing them. At the same time, culture manifests itself in some visible aspects of the organization’s environment. In this section, we discuss five ways in which culture shows itself to observers and employees.

Mission Statement

A mission statement is a statement of purpose, describing who the company is and what it does. Many companies have mission statements, but they do not always reflect the company’s values and its purpose. An effective mission statement is well known by employees, is transmitted to all employees starting from their first day at work, and influences employee behaviour.

These are some examples:

“To accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy.” : Tesla

“To connect the world’s professionals to make them more productive and successful.” : LinkedIn

“To be Earth’s most customer-centric company, where customers can find and discover anything they might want to buy online, and endeavors to offer its customers the lowest possible prices.” : Amazon

Not all mission statements are effective, because some are written by public relations specialists and can be found in a company’s website, but it does not affect how employees act or behave. In fact, some mission statements reflect who the company wants to be as opposed to who they actually are. If the mission statement does not affect employee behaviour on a day-to-day basis, it has little usefulness as a tool for understanding the company’s culture. An oft-cited example of a mission statement that had little impact on how a company operates belongs to Enron. Their missions and values statement began, “As a partner in the communities in which we operate, Enron believes it has a responsibility to conduct itself according to certain basic principles.” Their values statement included such ironic declarations as “We do not tolerate abusive or disrespectful treatment. Ruthlessness, callousness and arrogance don’t belong here” (Kunen, 2002). The company filed for bankruptcy in 2001 after fraudulently stating its business results for years. Shareholders lost $74 billion.

A mission statement that is taken seriously and widely communicated may provide insights into the corporate culture. For example, the Mayo Clinic’s mission statement is “The needs of the patient come first.” This mission statement evolved from the founders who are quoted as saying, “The best interest of the patient is the only interest to be considered.” Mayo Clinics have a corporate culture that puts patients first. For example, no incentives are given to physicians based on the number of patients they see. Because doctors are salaried, they have no interest in retaining a patient for themselves and they refer the patient to other doctors when needed (Jarnagin & Slocum, 2007). Wal-Mart Stores Inc. may be another example of a company who lives its mission statement, and therefore its mission statement may give hints about its culture: “Saving people money so they can live better” (Wal-Mart, 2008). In fact, their culture emphasizes thrift and cost control in everything they do. For example, even though most CEOs of large companies in the United States have lavish salaries and showy offices, Wal-Mart’s CEO Michael Duke and other high-level corporate officers work out of modest offices in the company’s headquarters.

Rituals

Rituals refer to repetitive activities within an organization that have symbolic meaning (Anand, 2005). Usually rituals have their roots in the history of a company’s culture. They create camaraderie and a sense of belonging among employees. They also serve to teach employees corporate values and create identification with the organization.

For example, at the cosmetics firm Mary Kay Inc., (the sixth largest network marketing company in the world in 2018, with a wholesale volume of US$3.25 billion) employees attend award ceremonies recognizing their top salespeople with an award of a new car—traditionally a pink Cadillac. These ceremonies are conducted in large auditoriums where participants wear elaborate evening gowns and sing company songs that create emotional excitement. During this ritual, employees feel a connection to the company culture and its values, such as self-determination, will power, and enthusiasm (Jarnagin & Slocum, 2007).

Another example of rituals is the Saturday morning meetings of Wal-Mart. This ritual was first created by the company founder Sam Walton, who used these meetings to discuss which products and practices were doing well and which required adjustment. He was able to use this information to make changes in Wal-Mart’s stores before the start of the week, which gave him a competitive advantage over rival stores who would make their adjustments based on weekly sales figures during the middle of the following week. Today, hundreds of Wal-Mart associates attend the Saturday morning meetings in the Bentonville, Arkansas, headquarters. The meetings, which run from 7:00 to 9:30 a.m., start and end with the Wal-Mart cheer; the agenda includes a discussion of weekly sales figures and merchandising tactics. As a ritual, the meetings help maintain a small-company atmosphere, ensure employee involvement and accountability, communicate a performance orientation, and demonstrate taking quick action (Schlender, 2005; Wal around the world, 2001).

Rules and Policies

Another way in which an observer may find out about a company’s culture is to examine its rules and policies. Companies create rules to determine acceptable and unacceptable behaviour, and thus the rules that exist in a company will signal the type of values it has. Policies about issues such as decision making, human resources, and employee privacy reveal what the company values and emphasizes. For example, a company that has a policy such as “all pricing decisions of merchandise will be made at corporate headquarters” is likely to have a centralized culture that is hierarchical, as opposed to decentralized and empowering. Similarly, a company that extends benefits to both part-time and full-time employees, as well as to spouses and domestic partners, signals to employees and observers that it cares about its employees and shows concern for their well-being. By offering employees flexible work hours, sabbaticals, and telecommuting opportunities, a company may communicate its emphasis on work-life balance. The presence or absence of policies on sensitive issues such as English-only rules, bullying or unfair treatment of others, workplace surveillance, open-door policies, sexual harassment, workplace romances, and corporate social responsibility all provide pieces of the puzzle that make up a company’s culture.

Physical Layout

A company’s building, including the layout of employee offices and other work spaces, communicates important messages about a company’s culture. The building architecture may indicate the core values of an organization’s culture. For example, visitors walking into the Nike Inc. campus in Beaverton, Oregon, can witness firsthand some of the distinguishing characteristics of the company’s culture. The campus is set on 74 acres and boasts an artificial lake, walking trails, soccer fields, and cutting-edge fitness centers. The campus functions as a symbol of Nike’s values such as energy, physical fitness, an emphasis on quality, and a competitive orientation. In addition, at fitness centers on the Nike headquarters, only those wearing Nike shoes and apparel are allowed in. This sends a strong signal that loyalty is expected. The company’s devotion to athletes and their winning spirits is manifested in campus buildings named after famous athletes, photos of athletes hanging on the walls, and honorary statues dotting the campus (Capowski, 1993; Collins & Porras, 1996; Labich & Carvell, 1995; Mitchell, 2002). A very different tone awaits visitors to Wal-Mart headquarters, where managers have gray and windowless offices (Berner, 2007). By putting its managers in small offices and avoiding outward signs of flashiness, Wal- Mart does a good job of highlighting its values of economy.

Stories

Perhaps the most colorful and effective way in which organizations communicate their culture to new employees and organizational members is through the skillful use of stories. A story can highlight a critical event an organization faced and the collective response to it, or can emphasize a heroic effort of a single employee illustrating the company’s values. The stories usually engage employee emotions and generate employee identification with the company or the heroes of the tale. A compelling story may be a key mechanism through which managers motivate employees by giving their behaviour direction and energizing them toward a certain goal (Beslin, 2007).

In this video Airbnb tells a real story of how two men who lived on the either side of the Berlin Wall (when Germany was separated as West Germany – a democracy and East Germany – a communist country) met each other in surprisingly unexpected and yet happy circumstances. The story highlights Airbnb’s culture of building a sense of belonging with its guests.

14.5 Changing An Organizational Culture

How Do Cultures Change?

Culture is part of a company’s DNA and is resistant to change efforts. Unfortunately, many organizations may not even realize that their current culture constitutes a barrier against organizational productivity and performance. Changing company culture may be the key to the company turnaround when there is a mismatch between an organization’s values and the demands of its environment.

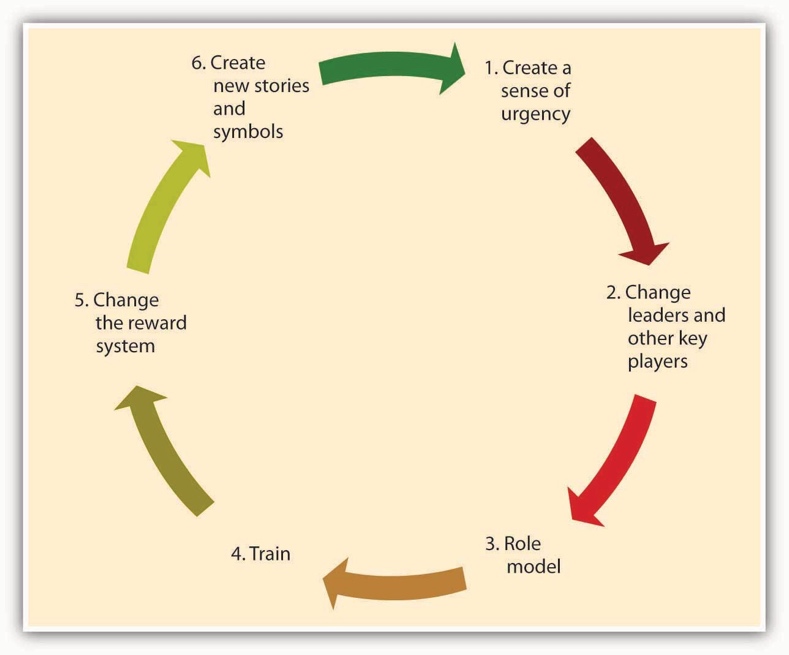

Certain conditions may help with culture change. For example, if an organization is experiencing failure in the short run or is under threat of bankruptcy or an imminent loss of market share, it would be easier to convince managers and employees that culture change is necessary. A company can use such downturns to generate employee commitment to the change effort. However, if the organization has been successful in the past, and if employees do not perceive an urgency necessitating culture change, the change effort will be more challenging. Sometimes the external environment may force an organization to undergo culture change. Mergers and acquisitions are another example of an event that changes a company’s culture. In fact, the ability of the two merging companies to harmonize their corporate cultures is often what makes or breaks a merger effort. When Ben & Jerry’s was acquired by Unilever, Ben & Jerry’s had to change parts of its culture while attempting to retain some of its unique aspects. Corporate social responsibility, creativity, and fun remained as parts of the culture. In fact, when Unilever appointed a veteran French executive as the CEO of Ben & Jerry’s in 2000, he was greeted by an Eiffel tower made out of ice cream pints, Edith Piaf songs, and employees wearing berets and dark glasses. At the same time, the company had to become more performance oriented in response to the acquisition. All employees had to keep an eye on the bottom line. For this purpose, they took an accounting and finance course for which they had to operate a lemonade stand (Kiger, 2005). Achieving culture change is challenging, and many companies ultimately fail in this mission. Research and case studies of companies that successfully changed their culture indicate that the following six steps increase the chances of success (Schein, 1990).

1. Creating a Sense of Urgency

In order for the change effort to be successful, it is important to communicate the need for change to employees. One way of doing this is to create a sense of urgency on the part of employees and explain to them why changing the fundamental way in which business is done is so important. In successful culture change efforts, leaders communicate with employees and present a case for culture change as the essential element that will lead the company to eventual success. As an example, consider the situation at IBM Corporation in 1993 when Lou Gerstner was brought in as CEO and chairman. After decades of dominating the market for mainframe computers, IBM was rapidly losing market share to competitors, and its efforts to sell personal computers—the original “PC”—were seriously undercut by cheaper “clones.” In the public’s estimation, the name IBM had become associated with obsolescence. Gerstner recalls that the crisis IBM was facing became his ally in changing the organization’s culture. Instead of spreading optimism about the company’s future, he used the crisis at every opportunity to get buy-in from employees (Gerstner, 2002).

2. Changing Leaders and Other Key Players

A leader’s vision is an important factor that influences how things are done in an organization. Thus, culture change often follows changes at the highest levels of the organization. Moreover, in order to implement the change effort quickly and efficiently, a company may find it helpful to remove managers and other powerful employees who are acting as a barrier to change. Because of political reasons, self-interest, or habits, managers may create powerful resistance to change efforts. In such cases, replacing these positions with employees and managers giving visible support to the change effort may increase the likelihood that the change effort succeeds. For example, when Robert Iger replaced Michael Eisner as CEO of the Walt Disney Company, one of the first things he did was to abolish the central planning unit, which was staffed by people close to ex-CEO Eisner. This department was viewed as a barrier to creativity at Disney, and its removal from the company was helpful in ensuring the innovativeness of the company culture (McGregor et al., 2007).

3. Role Modeling

Role modeling is the process by which employees modify their own beliefs and behaviours to reflect those of the leader (Kark & Dijk, 2007). CEOs can model the behaviours that are expected of employees to change the culture. The ultimate goal is that these behaviours will trickle down to lower level employees. For example, when Robert Iger took over Disney, in order to show his commitment to innovation, he personally became involved in the process of game creation, attended summits of developers, and gave feedback to programmers about the games. Thus, he modeled his engagement in the idea creation process. In contrast, modeling of inappropriate behaviour from the top will lead to the same behaviour trickling down to lower levels. A recent example of this type of role modeling is the scandal involving Hewlett-Packard Development Company LP board members. In 2006, when board members were suspected of leaking confidential company information to the press, the company’s top-level executives hired a team of security experts to find the source of the leak. The investigators sought the phone records of board members, linking them to journalists. For this purpose, they posed as board members and called phone companies to obtain the itemized home phone records of board members and journalists. When the investigators’ methods came to light, HP’s chairman and four other top executives faced criminal and civil charges. When such behaviour is modeled at top levels, it is likely to have an adverse impact on the company culture (Barron, 2007).

4. Training

Well-crafted training programs may be instrumental in bringing about culture change by teaching employees the new norms and behavioural styles. For example, after the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon reentry from a February 2003 mission, NASA decided to change its culture to become more safety sensitive and minimize decision-making errors leading to unsafe behaviours. The change effort included training programs in team processes and cognitive bias awareness. Similarly, when auto repairer Midas International Corporation felt the need to change its culture to be more committed to customers, they developed a training program making employees familiar with customer emotions and helping form better connections with them. Customer reports have been overwhelmingly positive in stores that underwent this training (BST to guide culture change effort at NASA, 2004).

5. Changing the Reward System

The criteria with which employees are rewarded and punished have a powerful role in determining the cultural values in existence. Switching from a commission-based incentive structure to a straight salary system may be instrumental in bringing about customer focus among sales employees. Moreover, by rewarding employees who embrace the company’s new values and even promoting these employees, organizations can make sure that changes in culture have a lasting impact. If a company wants to develop a team-oriented culture where employees collaborate with each other, methods such as using individual-based incentives may backfire. Instead, distributing bonuses to intact teams might be more successful in bringing about culture change.

6. Creating New Symbols and Stories

Finally, the success of the culture change effort may be increased by developing new rituals, symbols, and stories. Continental Airlines Inc. is a company that successfully changed its culture to be less bureaucratic and more team oriented in the 1990s. One of the first things management did to show employees that they really meant to abolish many of the detailed procedures the company had and create a culture of empowerment was to burn the heavy 800-page company policy manual in their parking lot. The new manual was only 80 pages. This action symbolized the upcoming changes in the culture and served as a powerful story that circulated among employees. Another early action was the redecorating of waiting areas and repainting of all their planes, again symbolizing the new order of things (Higgins & McAllester, 2004). By replacing the old symbols and stories, the new symbols and stories will help enable the culture change and ensure that the new values are communicated.

14.6 Embedding Sustainability into Culture

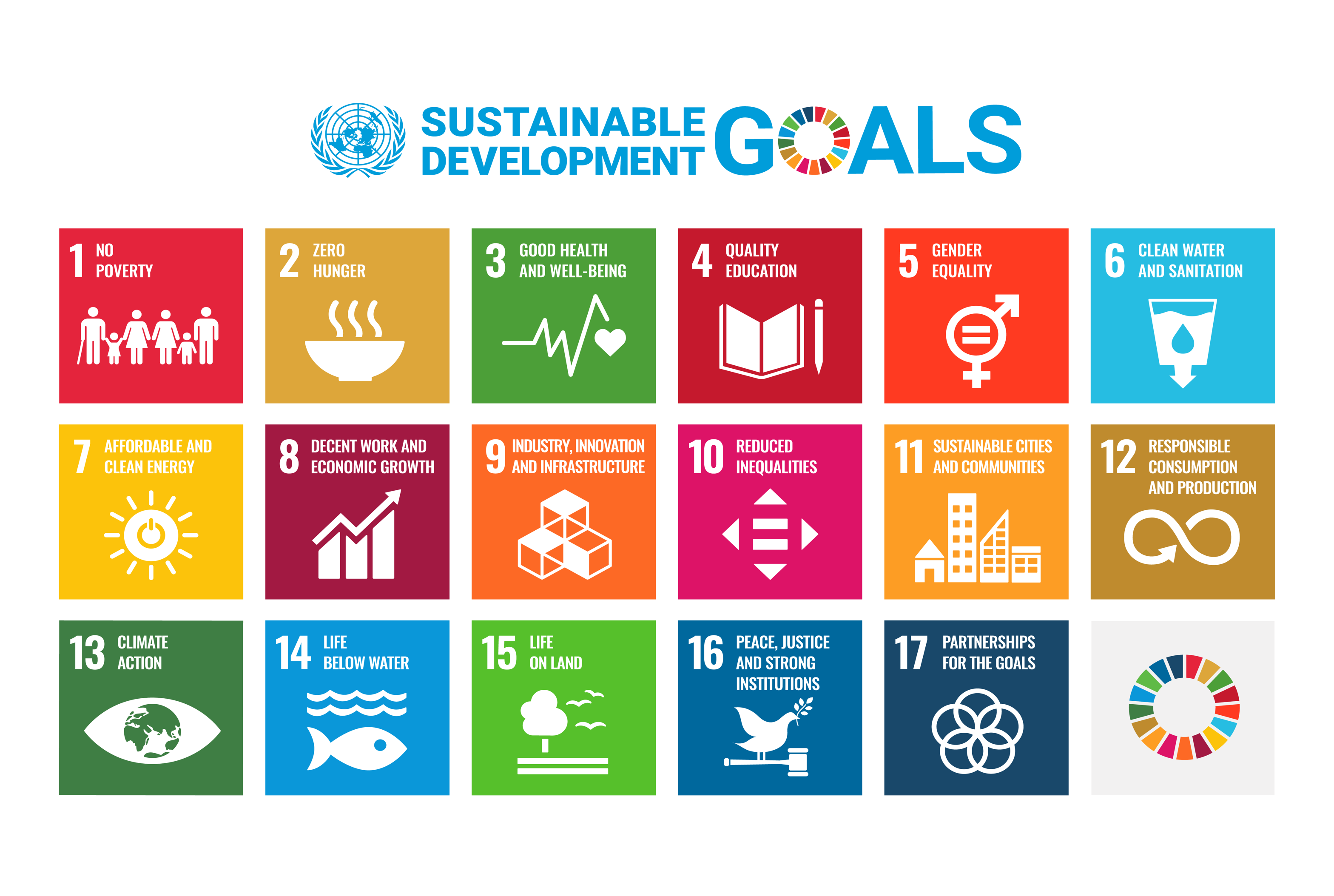

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that by 2030 all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

The 17 SDGs are integrated—they recognize that action in one area will affect outcomes in others, and that development must balance social, economic and environmental sustainability.

How do companies embed sustainability into their culture ?

Change is coming. Sustainability is now widely regarded as the next big revolution since the shift to digital and is disrupting the way that business gets done. For the environment and society, that’s a very good thing. But it adds extra pressure on the teams tasked with owning sustainability. While enterprises grapple to hit their compliance and risk management goals, they are also under pressure to develop sustainable consumer products, services and responsible social engagement.

Sustainability is the ability to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Businesses can achieve sustainability by reducing their environmental impact, integrating social responsibility into their operations, and, most importantly, developing a corporate culture of sustainability.

Recent data shows that 99% of organizations consider Sustainability and ESG (Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) are a key consideration for business.

E – Environment

This refers to a company’s ability to manage resources and prevent pollution. This criteria includes the energy a company takes in and the waste it discharges, the resources it needs and the consequences for living beings as a result. This could include the weather’s impact on selling seasons, emission regulation impacting supply chain logistics, plastic use and packaging. Environmental sustainability mainly impacts three different areas—climate, oceans and biodiversity.

S – Social

This refers to a company’s ability to identify and manage its business impact on people—or the steps a company takes to improve its social impact both within its company and greater community where they do business. This ensures that progress is made toward sustaining business operations that protects the supply chain and contributes to all stakeholder interests.

G – Governance

This refers to a company’s ability to establish the policies and leadership structure to ensure sustainability practices are put into place and supported. G is the internal system of practices, controls and procedures a company adopts in order to govern itself, make effective decisions, comply with the law and meet the needs of external stakeholders. Every company, which is itself a legal creation, requires governance.

Building a sustainability culture is hard work that begins with adopting a common language and understanding of sustainability goals. One of the challenges with building a sustainability culture is establishing a common terminology and having a shared sense of what sustainability is. Research by “The Conference Board” shows that most companies don’t have internal clarity on the meaning of sustainability. In a 2021 poll, the Board found that only a third (32 percent) of companies have a strong agreed-upon definition of sustainability across the business and there’s no universally accepted definition of sustainability. This lack of a common language makes it harder to build a sustainability culture, which by its very nature needs to be company specific.

Changing cultures is hard because it requires changing norms and values, often ones that are deeply held. Companies on a sustainability journey need to be sensitive to the culture that already exists and intentional about engaging people in implementing change. At one firm, for example, internal sustainability ambassadors run culture workshops where they discuss how sustainability objectives are integrated with the business and what behaviors are associated with achieving them, and videos of those workshops are shared on an internal website.

4 Steps to a Corporate Culture of Sustainability

Management needs to make sure that the strategy of the company and the sustainability efforts are aligned. The Center for Sustainable and Inclusive Business, often sees divergence, which of course makes the sustainability efforts fragile, lacking real commitment and prioritization. But there are many good examples. One such example is Unilever’s Planet Positive initiative, designed to give more than the company takes from the planet through plans to protect and regenerate 1.5 million hectares of land, forests, and oceans by 2030. Unilever says that is more land than it already uses to grow the renewable ingredients included in its beauty and personal care product range. And by 2025, the company says any plastic used in its packaging will be recyclable, reusable, or compostable.

Many of today’s leading companies in sustainability, like Nike, Coca-Cola, Telenor, IKEA, Siemens, and Nestlé, have stepped up largely as a consequence of a crisis. Oil giant Shell, already the focus of activist protests over drilling in the Arctic, faced boycott calls due its purchase of cheap Russian crude oil after Russia invaded Ukraine. Shell rapidly backed down and said it will exit all its Russian operations and write down up to $5 billion as a result.

All companies struggle with quantifying the return on their sustainability investments. How does the company justify expenses on sustainability initiatives ? With regards to compliance this is a straightforward issue. With regards to areas of competitive advantage, however, companies need to link sustainability to a business case. But the ones that do form a relatively small group.

In a McKinsey Global survey, respondents were asked whether their companies track the impact of ESG ( Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) programs on various stakeholder groups. The biggest percentage among those stakeholder groups, 51%, was for considering the impact on board directors “entirely or to a great extent”. This reinforces how important boards are in collaborations with key stakeholders such as NGOs, governments, and international organizations.

Collaboration is also critical for efficient sustainability practices, particularly in solving crises and in shaping broader solutions. MIT/BCG data showed that 67% of executives see sustainability as an area where collaboration is necessary to succeed. Finally, and most importantly, engage the organization broadly: One good example of engagement is Salesforce, a company so committed to making every employee and department accountable to sustainability that it recently enshrined it into its core values.

Now that sustainability is part of its DNA, the company can leverage its full might to advance climate action and further operationalize sustainability across its entire business.

The sustainable Seneca is one of the three pillars of Au Large, along with the equitable Seneca and the more virtual Seneca.

With the release of its first sustainability plan, Seneca is focusing on four priority themes: leadership, community, education and research, and operations.

Sustainability is a complex objective that goes well beyond the environment. It also includes social equity, cultural vitality and economic responsibility. Everyone at Seneca has a role to play. And, together, the institution is accepting the challenge to build the sustainable Seneca.

Read more on Sustainable Seneca

14.7 The Role of Ethics and National Culture

Organizational Culture and Ethics

A recent study of 3,000 employees and managers in the United States confirms that the degree to which employees in an organization behave ethically depends on the culture of the organization (Gebler, 2006). Without a culture emphasizing the importance of integrity, honesty, and trust, mandatory ethics training programs are often doomed to fail. Thus, creating such a culture is essential to avoiding the failures of organizations such as WorldCom and Enron. How is such a culture created?

The factors we highlighted in this chapter will play a role in creating an ethical culture. Among all factors affecting ethical culture creation, leadership may be the most influential. Leaders, by demonstrating high levels of honesty and integrity in their actions, can model the behaviours that are demanded in an organization. If their actions contradict their words, establishing a culture of ethics will be extremely difficult. As an example, former chairman and CEO of Enron Kenneth Lay forced all his employees to use his sister’s travel agency, even though the agency did not provide high-quality service or better prices (Watkins, 2003). Such behaviour at the top is sure to trickle down. Leaders also have a role in creating a culture of ethics because they establish the reward systems being used in a company. There is a relationship between setting very difficult goals for employees and unethical behaviour (Schweitzer, Ordonez, & Douma, 2004). When leaders create an extremely performance-oriented culture where only results matter and there is no tolerance for missing one’s targets, the culture may start rewarding unethical behaviours. Instead, in organizations such as General Electric Company where managers are evaluated partly based on metrics assessing ethics, behaving in an ethical manner becomes part of the core company values (Heineman, 2007).

Organizational Culture Around the Globe

The values, norms, and beliefs of a company may also be at least partially imposed by the national culture. When an entrepreneur establishes an organization, the values transmitted to the organization may be because of the cultural values of the founder and the overall society. If the national culture in general emphasizes competitiveness, a large number of the companies operating in this context may also be competitive. In countries emphasizing harmony and conflict resolution, a team-oriented culture may more easily take root. For example, one study comparing universities in Arab countries and Japan found that the Japanese universities were characterized by modesty and frugality, potentially reflecting elements of the Japanese culture. The study also found that the Arab universities had buildings that were designed to impress and had restricted access, which may be a reflection of the relatively high-power distance of the Arab cultures. Similarly, another study found that elements of Brazilian culture such as relationships being more important than jobs, tendency toward hierarchy, and flexibility were reflected in organizational culture values such as being hierarchical and emphasizing relational networks (Dedoussis, 2004; Garibaldi de Hilal, 2006). It is important for managers to know the relationship between national culture and company culture because the relationship explains why it would sometimes be challenging to create the same company culture globally.

14.8 Mini Case Scenario

MISSING THE MESSAGE