1 Introduction to Operations Management

Learning Objectives

- What is Operations Management?

- Describe the transformation process and some categories.

- Why should a business student study Operations Management?

- What are some of the Professional Organizations involved in Operations Management?

- Describe each of the three phases of Operations Management history.

- Discuss how producing goods is different from performing services.

Operations management is a vast topic but can be bundled into a few distinct categories, each of which will be covered in later units. (It should be noted that entire courses could be devoted to each of these topics individually). Since most people do not work in a formal operations department, we will begin with an overview of operations management itself.

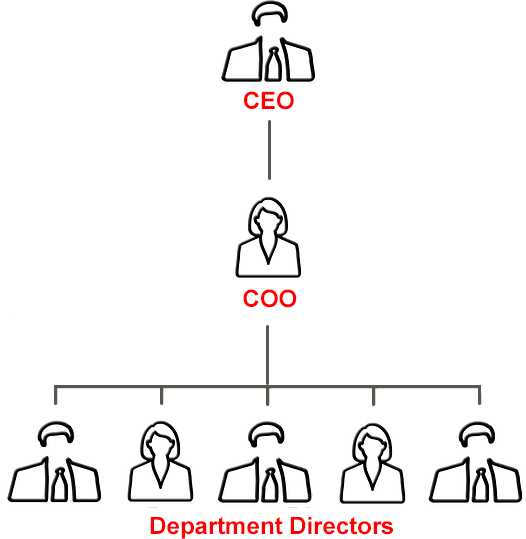

The top manager of an operations department is usually called the Director of Operations.

Most operations departments will report to a Chief Operating Officer (COO), who reports to the Chief Executive Officer (CEO).

The COO is often considered the most important figure in a firm, next to the CEO.

The history of operations management can be traced back to the industrial revolution when production began to shift from small, local companies to large-scale production firms. One of the most significant contributions to operations management came in the early 20th century when Henry Ford pioneered the assembly line manufacturing process. This process drastically improved productivity and made automobiles affordable to the masses. Understanding the motivations behind innovations of the past can help us identify factors that may motivate individuals in the future of operations management.

What is Operations Management?

Operations management is the management of the processes that transform inputs into the goods and services that add value for the customer. Consider the ingredients of your breakfast this morning. Unless you live on a farm and produced them yourself, they passed through a number of different processing steps between the farmer and your table and were handled by several different organizations.

Every day, you use a multitude of physical objects and a variety of services. Most of the physical objects have been manufactured and most of the services have been provided by people in organizations. Just as fish are said to be unaware of the water that surrounds them, most of us give little thought to the organizational processes that produce these goods and services for our use. The study of operations deals with how the goods and services that you buy and consume every day are produced.

The following video shows some of the basic strategic areas in operations management. We will cover some of these areas in addition to some tools and techniques used in operations management.

Transformation Processes

A transformation process is any activity or group of activities that takes one or more inputs, transforms and adds value to them, and provides outputs for customers or clients. Where the inputs are raw materials, it is relatively easy to identify the transformation involved, such as when milk is transformed into cheese or butter. Where the inputs are information or people, the nature of the transformation may be less obvious. For example, a hospital transforms ill patients (the input) into healthy patients (the output).

Examples of Transformation Processes

- changes in the physical characteristics of materials or customers

- changes in the location of materials, information or customers

- changes in the ownership of materials or information

- storage or accommodation of materials, information or customers

- changes in the purpose or form of information

- changes in the physiological or psychological state of customers

Often all three types of input – materials, information and customers – must be transformed by a single organisation. For example, withdrawing money from a bank account involves information about the customer’s account, materials (such as cheques and currency), and the customer. Treating a patient in hospital involves not only the “customer’s” state of health, but also any materials used in treatment and information about the patient.

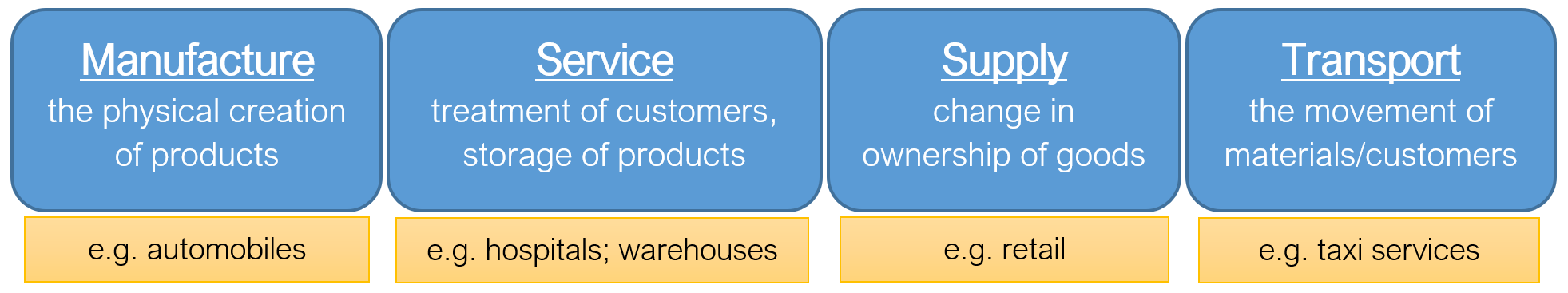

As Figure 1.2 demonstrates, transformation processes can be categorized into four groups: manufacture (the physical creation of products, e.g. automobiles), service (the treatment of customers or storage of products, e.g. hospitals or warehouses), supply (a change in ownership of goods, e.g. retail), and transport (the movement of materials or customers, e.g. taxi service).

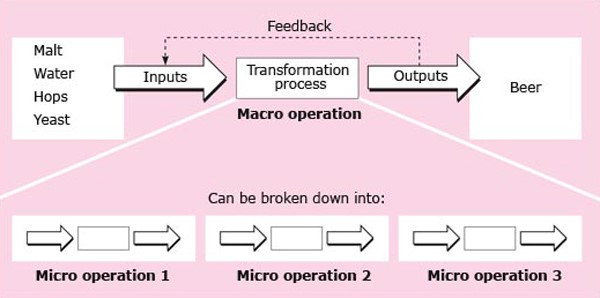

Several different transformations are usually required to produce a good or service. The overall transformation can be described as the macro operation, and the more detailed transformations within this macro operation as micro operations. For example, the macro operation in a brewery is making beer (Figure 1.3). The micro operations include:

- milling the malted barley into grist

- mixing the grist with hot water to form wort

- cooling the wort and transferring it to the fermentation vessel

- adding yeast to the wort and fermenting the liquid into beer

- filtering the beer to remove the spent yeast

- decanting the beer into casks or bottles.

The Operations Function

Every organization has an operations function, whether or not it is called ‘operations’. The goal or purpose of most organizations involves the production of goods and/or services. To do this, they have to procure resources, convert them into outputs and distribute them to their intended users. The term operations embraces all the activities required to create and deliver an organization’s goods or services to its customers or clients.

Within large and complex organizations, operations is usually a major functional area, with people specifically designated to take responsibility for managing all or part of the organization’s operations processes. It is an important functional area because it plays a crucial role in determining how well an organization satisfies its customers. In the case of private-sector companies, the mission of the operations function is usually expressed in terms of profits, growth and competitiveness; in public and voluntary organizations, it is often expressed in terms of providing value for money.

Operations management is concerned with the design, management, and improvement of the systems that create the organization’s goods or services. The majority of most organizations’ financial and human resources are invested in the activities involved in making products or delivering services. Operations management is therefore critical to organizational success.

Other functions of the Business :

A typical organization has four distinct basic functional areas; operations, marketing and sales, finance, and human resources. Operations is the area that is responsible for directly creating the product or service for which the customer will pay. The other three departments ensure that the operations of the business has everything needed in order to do the work.

Marketing – ensures that operations is producing the right product or service in a way that provides customers with all the features or characteristics that they value.

Finance – ensures that the funds for materials, supplies, payroll and equipment are available when needed.

Human Resources – ensures that the correct employees, with the adequate skills and experience are recruited, hired and trained. They are responsible for compensation, collection of income taxes, administration of benefits, succession planning and more. Without HR, there would be no employees in the operations department.

Why should I study Operations Management?

In most organizations, operations tends to be the largest department in terms of the number of employees. For a new graduate, you may be smart to look for a position within the operations of a business. In a larger company these jobs are far more plentiful than those in smaller departments. If you have a passion for working for a large organization, you might want to focus more on which organization you go to work for, and less focus on the actual job title. Soon enough, if you’re punctual, energetic and proactive, you will likely apply or get promoted into the job you desire.

Operations is where the largest share of the firm’s dollars are spent. It is a huge focus of top management.

All other departments in the organization are interrelated with operations. In finance, marketing and human resources, you will be interacting with operations on a regular basis. You should understand the businesses’ core transformation process regardless of the department in which you work.

Major innovations are made through operations. If you look at successful companies such as Toyota, Amazon, or Dell, you will find that the keys to their success came from innovations to the operations processes of their businesses.

Operational innovation means coming up with entirely new ways of filling orders, developing products, providing customer service, or doing any other activity that an enterprise performs.

- Effectiveness refers to making the right actions and plans in order to improve the business and add value for the customer. It is helping to get the business doing the right things for the customer.

- Efficiency is different. To be efficient means doing things well at the lowest cost possible. To be efficient, we look for ways to reduce unnecessary or redundant activities that add unnecessary cost and could be avoided.

Resources for Operations Management learners and professionals:

- Supply Chain Management Association (SCMA)

- Canadian Institute of Traffic and Transportation (CITT)

- Association for Supply Chain Management (APICS)

- American Society for Quality (ASQ)

- Project Management Institute (PMI)

Activity:

Look at ONE of the Associations above and answer the following questions:

- Is this organization Canadian, or multinational?

- Is there an opportunity for students to join? If yes, is there a fee, and how much?

- Are there opportunities for networking and to meet professionals?

- Do they offer job search assistance?

- Would you consider joining either of these organizations? Why or why not?

Development of Operations Management

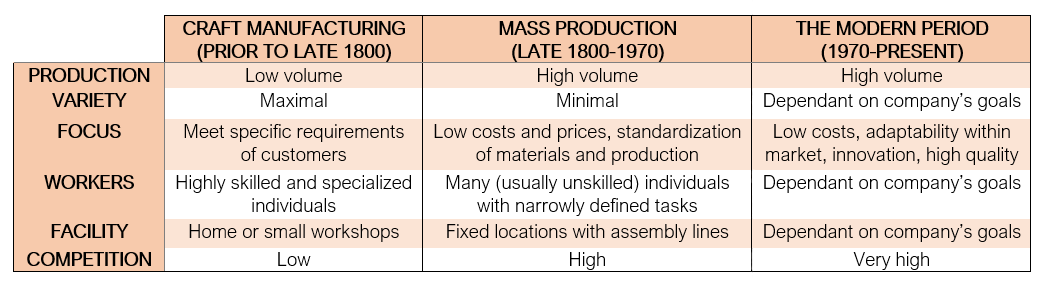

Operations in some form have been around as long as human endeavor itself but, in manufacturing at least, it has changed dramatically over time, and there are three major phases – craft manufacturing, mass production and the modern period. Let’s look at each of these briefly in turn.

Craft manufacturing

Craft manufacturing describes the process by which skilled craftspeople produce goods in low volume, with a high degree of variety, to meet the requirements of their individual customers. Over the centuries, skills have been transmitted from masters to apprentices and journeymen, and controlled by guilds. Craftspeople usually worked at home or in small workshops. Such a system worked well for small-scale local production, with low levels of competition. Some industries, such as furniture manufacture and clock-making, still include a significant proportion of craft working.

Mass production

In many industries, craft manufacturing began to be replaced by mass production in the 19th century. Mass production involves producing goods in high volume with low variety – the opposite of craft manufacturing. Customers are expected to buy what is supplied, rather than goods made to their own specifications. Producers concentrated on keeping costs, and hence prices, down by minimizing the variety of both components and products and setting up large production runs. They developed aggressive advertising and employed sales forces to market their products.

An important innovation in operations that made mass production possible was the system of standardized and interchangeable parts known as the “American system of manufacture” (Hounshell, 1984), which developed in the United States and spread to the United Kingdom and other countries. Instead of being produced for a specific machine or piece of equipment, parts were made to a standard design that could be used in different models. This greatly reduced the amount of work required in cutting, filing and fitting individual parts, and meant that people or companies could specialize in particular parts of the production process.

A second innovation was the development by Frederick Taylor (1911) of the system of ‘scientific management’, which sought to redesign jobs using similar principles to those used in designing machines. Taylor argued that the role of management was to analyze jobs in order to find the ‘one best way’ of performing any task or sequence of tasks, rather than allowing workers to determine how to perform their jobs. By breaking down activities into tasks that were sequential, logical and easy to understand, each worker would have narrowly defined and repetitious tasks to perform, at high speed and therefore with low costs (Kanigel, 1999).

A third innovation was the development of the moving assembly line by Henry Ford. Instead of workers bringing all the parts and tools to a fixed location where one car was put together at a time, the assembly line brought the cars to the workers. Ford thus extended the ideas of scientific management, with the assembly line controlling the pace of production. This completed the development of a system through which large volumes of standardized products could be assembled by unskilled workers at constantly decreasing costs – the apogee of mass production.

The modern period

Mass production worked well as long as high volumes of mass-produced goods could be produced and sold in predictable and slowly changing markets. However, during the 1970s, markets became highly fragmented, product life cycles reduced dramatically, and consumers had far greater choice than ever before.

An unforeseen challenge to Western manufacturers emerged from Japan. New Japanese production techniques, such as total quality management (TQM), just-in-time (JIT) and employee involvement were emulated elsewhere in the developed world with mixed results. More recently, the mass production paradigm has been replaced, but there is yet no single approach to managing operations that has become similarly dominant. The different approaches for managing operations that are currently popular include:

- Flexible specialization (Piore and Sabel, 1984) in which firms (especially small firms) focus on separate parts of the value-adding process and collaborate within networks to produce whole products. Such an approach requires highly developed networks, effective processes for collaboration and the development of long-term relationships between firms.

- Lean production (Womack et al., 1990) which developed from the highly successful Toyota Production System. It focuses on the elimination of all forms of waste from a production system. A focus on driving inventory levels down also exposes inefficiencies, reduces costs, and cuts lead times.

- Mass customisation (Pine et al., 1993) which seeks to combine high volume, as in mass production, with adapting products to meet the requirements of individual customers. Mass customisation is becoming increasingly feasible with the advent of new technology and automated processes.

- Agile manufacturing (Kidd, 1994) which emphasizes the need for an organization to be able to switch frequently from one market-driven objective to another. Again, agile manufacturing has only become feasible on a large scale with the advent of enabling technology.

In various ways, these approaches all seek to combine the high volume and low cost associated with mass production with the product customization, high levels of innovation and high levels of quality associated with craft production.

Producing Goods and Services

The production and goods and the performance of services are both part of operations management. There are however some key differences in the two.

In the production of goods the result is the creation of a tangible product such as a vehicle, an article of clothing, a cell phone or a shovel. A service on the other hand is an intangible such as a car repair, a haircut, or a medical treatment. There are some key differences in managing these two types of businesses.

- Services have a much higher amount of customer contact. The customer will generally come to the service provider for the service to take place, or the service provider will come to the customer.

- In manufacturing the customer rarely comes to our facility. The purchase generally takes place at a different location than the one where the manufacturing occurred. That simplifies matters quite a bit.

- Services have a higher amount of labour content than manufacturing organizations.

. - Services have a much higher degree of input variability than do manufacturing companies. Each customer often arrives to a service with a unique set of circumstances that may require extra time and skills on the part of the service provider.

. - Measurement of quality is much more straight-forward in a manufacturing setting. There are many technical ways of deciding if manufactured goods have the required quality level.

- In services many factors will affect the customers impression of the quality of the service received.

- Measurement of productivity is very straight-forward in a manufacturing operation due to high degree of standardization in the inputs and outputs used.

- In services it is more difficult to measure productivity.

- Inventory can be stored in the case of a manufacturing organization. If goods are not sold in the intended week, then they can be put into storage to be sold at a later date.

- In services, once the time period has passed, the opportunity to use that capacity is gone.