9.5 The Monetary Base and the Money Supply

Table 8.1 showed that bank deposits are the major component of the money supply in Canada, as in most industrial countries. Bank deposits depend in turn on the cash reserves held by banks and the public’s willingness to hold bank deposits and borrow from the banks.

To complete our analysis of how the money supply is determined, we need to examine three things:

The source of the cash in the economy.

The amount of that cash that is deposited in the banking system, rather than held as cash balances by the public.

The relationship between the cash supply to the economy and the money supply that results from public and bank behaviour.

Today, in developed countries, central banks are the source of bank reserves. The central bank, the Bank of Canada in Canada, controls the issue of token money in the form of Bank of Canada notes. These are the $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100 bank notes you can withdraw from the bank when you wish to covert some of your bank balance to cash. Bank reserves are mainly the banks’ holdings of these central bank notes in their vaults and bank machines. Our bank deposits are now convertible into Bank of Canada notes. The central bank has the responsibility to manage the supply of cash in the economy.

The cash the central bank provides to the economy is called the monetary base (MB) and is sometimes referred to as the stock of high-powered money. It is the legal tender into which bank deposits can be converted. It is the ultimate means of payment in transactions and the settlement of debts. Notes and coins in circulation and held by the banking system are the main part of the money issued by the central bank. As we discussed earlier, the commercial banks hold small settlement balances in the central bank to make inter-bank payments arising from cheque clearings.

Monetary base (MB): legal tender comprising notes and coins in circulation plus the cash held by the banks.

The public’s decisions about the use of cash or banks deposits determine how much of the monetary base is held by the banks. The simple example of deposit creation in Table 8.4 assumed the public deposited all its cash with the banks. This was a useful simplification that ignores changes in the cash people hold. We will drop this assumption in what follows.

Our main interest is the relationship between the money supply in the economy, the total of cash in circulation plus bank deposits, and the monetary base created by the central bank. Assuming the public holds just a small fixed amount of cash and using our earlier discussion of the fractional reserve ratio in the banking system, we can define a deposit multiplier. The deposit multiplier provides the link between the monetary base created by the central bank and the money supply in the economy. It also predicts the change in money supply that would result from a change in the monetary base supplied by the central bank.

Deposit multiplier: the change in the bank deposits caused by a change in the monetary base.

Bank deposits= deposit multiplier × bank reserves

Deposit multiplier=Δ deposits / Δ bank reserves

The value of the deposit multiplier depends on rr, the banks’ ratio of cash reserves to total deposits. Banks’ choice of a ratio of cash reserves to total deposits (rr) determines how much they can expand lending and create bank deposits based on their reserve holdings. The lower the reserve ratio (rr), the more deposits banks can create against given cash reserves, and the larger is the multiplier. This is the relationship illustrated in Table 8.4.

Similarly, the lower the non-bank public’s holding of cash, the larger is the share of the monetary base held by the banks. When the banks hold more monetary base, they can create more bank deposits. The lower the non-bank public’s currency ratio, the larger are bank holdings of monetary base and the larger the money supply for any given monetary base.

The Money Multiplier

Suppose banks wish to hold cash reserves R equal to a fraction rr of their deposits D. Then:

Bank cash reserves = reserve ratio × deposits,

R = rrD (8.2)

To keep the example simple assume that we can ignore the small amount of cash held by the non-bank sector. As a result, the monetary base is mainly held as cash in bank vaults and automatic banking machines. This means from Equation 8.2 that:

Monetary base = reserve ratio × deposits,

MB = rrD (8.3)

and the deposit multiplier, which defines the change in total deposits as a result of a change in the monetary base, is:

Change in deposits = change in monetary base divided by the reserve ratio,

ΔD / ΔMB = 1 / rr (8.4)

which will be greater than 1 as long as rr is less than 1.

If, for example, banks want to hold cash reserves equal to 5 percent, and the non-bank public does not change their holdings of cash, the deposit multiplier will be:

ΔD / ΔMB = 10.05 = 20

When public cash holdings are constant, the deposit multiplier tells us how much deposits (and therefore the money supply in the economy), notes, and coins in circulation (outside the banks and bank deposits) would change as a result of a change in the monetary base. In this example, a $1 change in the monetary base results in a change in deposits and the money supply equal to $20.

Money supply (M)=cash in circulation+bank deposits (D)

M = cash + (R/rr) (8.5)

We can see from the way we have found the deposit multiplier that it depends on the decisions made by the banks in terms of their reserve holdings. For simplicity the public holds a fixed amount of cash in addition to bank deposits as money. If you experiment with different values for rr, you will see how the deposit and money multiplier would change if the reserve ratio were to change. Furthermore, if the public were to change their cash holdings the cash reserves available to the banks would change and the deposit multiplier would cause a larger change in the money supply.

The importance of bank reserve decisions and public cash holdings decisions is illustrated by recent financial conditions in Europe. As a result of banking crisis and bailouts during and after the financial crisis of 2008, the public had concerns about the safety of bank deposits and decided to hold more cash. At the same time banks found it difficult to evaluate the credit worthiness of potential borrowers and the risks involved in short-term corporate lending or junior government bonds. The public’s cash holdings increased and the banks increased their reserve ratios. These shifts in behaviour would reduce the money supply, making credit conditions tighter, unless the central bank provided offsetting increases in the monetary base.

How big is the money multiplier?

Now that we have a formula for the money multiplier, we can ask: What is the size of the multiplier in Canada? Based on data in Table 8.1 above, in January 2017, the monetary base was $84.6 billion, and the money supply defined as M1B was $814.8 billion. These data suggest a bank reserve ratio with respect of M1B =$84.6/$814.8 which is approximately 10.4 percent giving a money supply multiplier of 1/0.104=9.6.

ΔM / ΔMB = $814.8 / $84.6 = 9.6

Each $100 change in monetary base would change the money supply by about $960.

However, using a broader definition of money supply such as ‘currency outside banks and all chartered bank deposits’ gives a Canadian money supply of $1,510.5 and a money multiplier of $1,510.5/$84.6 = 17.85.

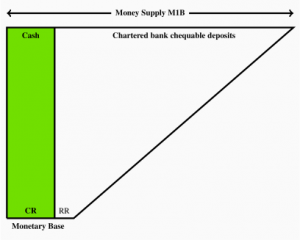

Figure 8.1 summarizes the relationship between the monetary base and the money supply. It shows the monetary base used either as cash in circulation or held as cash reserves by the banks. Since banks operate with fractional reserve ratios, the leverage banks have to expand the money supply through their lending and deposits creation based on their reserves RR. We also see that the money supply is heavily dependent on the size of the monetary base, reserve ratios used by the banks and the willingness of the public to hold bank deposits and the willingness of the banks to lend.

Figure 8.1 The monetary base and the money supply

The explanation of banking and the money supply in this chapter provides the money supply function we will use in the next chapter. It is combined there with a demand for money function in the money market to determine the equilibrium rate of interest. That rate of interest integrates money and financial markets with the markets for goods and services in aggregate demand.

A simple money supply function illustrates the determinants of the money supply. The three key variables are:

MB, the monetary base;

the public’s holdings of cash; and

rr, the banks’ reserve ratio.

Using Equation 8.5 above, where M is the money supply, we can write:

M = (1/rr) × MB (8.6)

The central bank’s control of the monetary base, MB, gives it control of the money supply, M, as long as cash holdings and rr are constant.

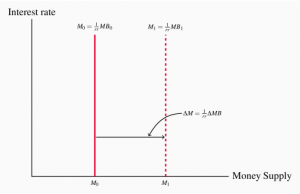

Figure 8.2 uses a diagram to illustrate the money supply function and changes in the money supply. The line M0 shows the size of the money supply for a given monetary base MB0 and the money multiplier. The money supply in this diagram is vertical, because we assume cash holdings and the reserve ratio are not affected by the interest rate. M is therefore independent of the nominal interest rate i, which is measured on the vertical axis. This is the supply side of the money market with quantity measured on the horizontal axis and interest rate, which is analogous to price, on the vertical axis.

Figure 8.2 The money supply function

The vertical M1 illustrates the increase in the money supply as a result of an increase in monetary base from MB0 to MB1, working through the money multiplier. A reduction in the monetary base would shift the M line to the left based on the same relationship.

Monetary policy

The central bank conducts monetary policy through its control of the monetary base. The money supply function shows us how, if rr is constant, the central bank’s control of the monetary base gives it the power to change money supply and other financial conditions in the economy. If the central bank increases the monetary base, banks have larger cash reserves and increase their lending, offering favourable borrowing rates to attract new loans and create more deposits. In Figure 8.2 the increase in the monetary base to MB1 causes an increase in money supply (ΔM) by the change in MB (ΔMB), multiplied by the money multiplier. The money supply function shifts to the right to M1. A decrease in the monetary base would shift the M function to the left, indicating a fall in the money supply.