5.3 Unemployment

Learning Objectives

- Explain how unemployment is measured in Canada.

- Define three different types of unemployment.

- Define and illustrate graphically what is meant by the natural level of employment. Relate the natural level of employment to the natural rate of unemployment.

For an economy to produce all it can and achieve a solution on its production possibilities curve, the factors of production in the economy must be fully employed. Failure to fully employ these factors leads to a solution inside the production possibilities curve in which society is not achieving the output it is capable of producing.

In thinking about the employment of society’s factors of production, we place special emphasis on labour. The loss of a job can wipe out a household’s entire income; it is a more compelling human problem than, say, unemployed capital, such as a vacant apartment. In measuring unemployment, we thus focus on labour rather than on capital and natural resources.

Measuring Unemployment

Statistics Canada defines a person as unemployed if he or she is not working but is looking for and available for work. The labour force is the total number of people working or unemployed. The unemployment rate is the percentage of the labour force that is unemployed.

To estimate the unemployment rate, government uses the information they collect in surveys of various Canadian households. At each of these randomly selected households, the surveyor asks about the employment status of each adult (everyone age 15 or over) who lives there. Many households include more than one adult; the survey gathers information on about roughly 100,000 adults. The surveyor asks if each adult is working. If the answer is yes, the person is counted as employed. If the answer is no, the surveyor asks if that person has looked for work at some time during the previous four weeks and is available for work at the time of the survey. If the answer to that question is yes, the person is counted as unemployed. If the answer is no, that person is not counted as a member of the labour force. Figure 5.8 “Computing the Unemployment Rate” shows the survey’s results for the civilian (nonmilitary) population for November 2010. The unemployment rate is then computed as the number of people unemployed divided by the labour force—the sum of the number of people not working but available and looking for work plus the number of people working.

A monthly survey of households divides the civilian adult population into three groups. Those who have jobs are counted as employed; those who do not have jobs but are looking for them and are available for work are counted as unemployed; and those who are not working and are not looking for work are not counted as members of the labor force. The unemployment rate equals the number of people looking for work divided by the sum of the number of people looking for work and the number of people employed.

The problem of understating unemployment among women has been fixed, but others remain. A worker who has been cut back to part-time work still counts as employed, even if that worker would prefer to work full time. A person who is out of work, would like to work, has looked for work in the past year, and is available for work, but who has given up looking, is considered a discouraged worker. Discouraged workers are not counted as unemployed, but a tally is kept each month of the number of discouraged workers.

The official measures of employment and unemployment can yield unexpected results. For example, when firms expand output, they may be reluctant to hire additional workers until they can be sure the demand for increased output will be sustained. They may respond first by extending the hours of employees previously reduced to part-time work or by asking full-time personnel to work overtime. None of that will increase employment, because people are simply counted as “employed” if they are working, regardless of how much or how little they are working. In addition, an economic expansion may make discouraged workers more optimistic about job prospects, and they may resume their job searches. Engaging in a search makes them unemployed again—and increases unemployment. Thus, an economic expansion may have little effect initially on employment and may even increase unemployment.

Types of Unemployment

Workers may find themselves unemployed for different reasons. Each source of unemployment has quite different implications, not only for the workers it affects but also for public policy.

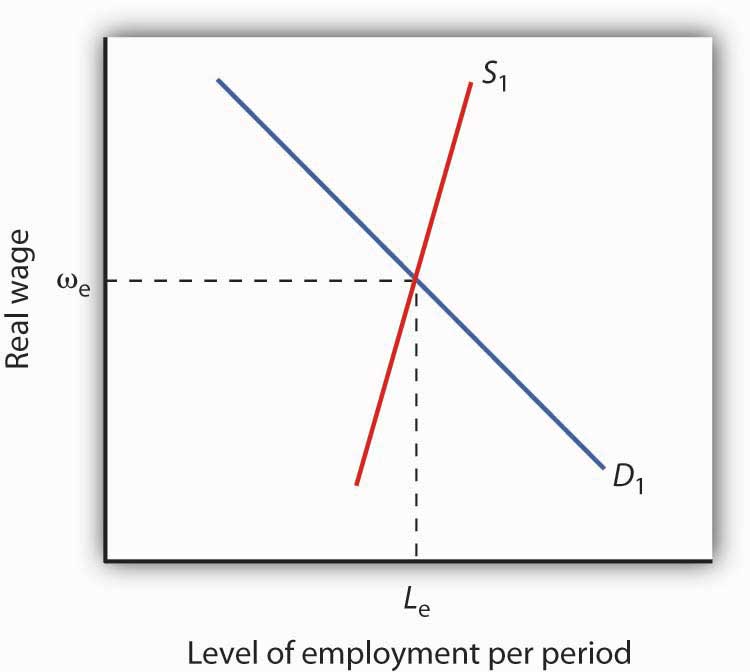

Figure 5.9 “The Natural Level of Employment” applies the demand and supply model to the labour market. The price of labour is taken as the real wage, which is the nominal wage divided by the price level; the symbol used to represent the real wage is the Greek letter omega, ω. The supply curve is drawn as upward sloping, though steep, to reflect studies showing that the quantity of labour supplied at any one time is nearly fixed. Thus, an increase in the real wage induces a relatively small increase in the quantity of labour supplied. The demand curve shows the quantity of labor demanded at each real wage. The lower the real wage, the greater the quantity of labour firms will demand. In the case shown here, the real wage, ωe, equals the equilibrium solution defined by the intersection of the demand curve D1 and the supply curve S1. The quantity of labour demanded, Le, equals the quantity supplied. The employment level at which the quantity of labour demanded equals the quantity supplied is called the natural level of employment. It is sometimes referred to as full employment.

Even if the economy is operating at its natural level of employment, there will still be some unemployment. The rate of unemployment consistent with the natural level of employment is called the natural rate of unemployment. Business cycles may generate additional unemployment. We discuss these various sources of unemployment below.

Frictional Unemployment

Even when the quantity of labour demanded equals the quantity of labour supplied, not all employers and potential workers have found each other. Some workers are looking for jobs, and some employers are looking for workers. During the time it takes to match them up, the workers are unemployed. Unemployment that occurs because it takes time for employers and workers to find each other is called frictional unemployment.

The case of college graduates engaged in job searches is a good example of frictional unemployment. Those who did not land a job while still in school will seek work. Most of them will find jobs, but it will take time. During that time, these new graduates will be unemployed. If information about the labor market were costless, firms and potential workers would instantly know everything they needed to know about each other and there would be no need for searches on the part of workers and firms. There would be no frictional unemployment. But information is costly. Job searches are needed to produce this information, and frictional unemployment exists while the searches continue.

Structural Unemployment

Another reason there can be unemployment even if employment equals its natural level stems from potential mismatches between the skills employers seek and the skills potential workers offer. Every worker is different; every job has its special characteristics and requirements. The qualifications of job seekers may not match those that firms require. Even if the number of employees firms demand equals the number of workers available, people whose qualifications do not satisfy what firms are seeking will find themselves without work. Unemployment that results from a mismatch between worker qualifications and the characteristics employers require is called structural unemployment.

Structural unemployment emerges for several reasons. Technological change may make some skills obsolete or require new ones. The widespread introduction of personal computers since the 1980s, for example, has lowered demand for typists who lacked computer skills.

Structural unemployment can occur if too many or too few workers seek training or education that matches job requirements. Students cannot predict precisely how many jobs there will be in a particular category when they graduate, and they are not likely to know how many of their fellow students are training for these jobs. Structural unemployment can easily occur if students guess wrong about how many workers will be needed or how many will be supplied.

Structural unemployment can also result from geographical mismatches. Economic activity may be booming in one region and slumping in another. It will take time for unemployed workers to relocate and find new jobs. And poor or costly transportation may block some urban residents from obtaining jobs only a few miles away.

Public policy responses to structural unemployment generally focus on job training and education to equip workers with the skills firms demand. The government publishes regional labour-market information, helping to inform unemployed workers of where jobs can be found. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) which is now called USMCA, created a free trade region encompassing Mexico, the United States, and Canada, has created some structural unemployment in the three countries.

Although government programs may reduce frictional and structural unemployment, they cannot eliminate it. Information in the labour market will always have a cost, and that cost creates frictional unemployment. An economy with changing demands for goods and services, changing technology, and changing production costs will always have some sectors expanding and others contracting—structural unemployment is inevitable. An economy at its natural level of employment will therefore have frictional and structural unemployment.

Cyclical Unemployment

Of course, the economy may not be operating at its natural level of employment, so unemployment may be above or below its natural level. In a later chapter we will explore what happens when the economy generates employment greater or less than the natural level. Cyclical unemployment is unemployment in excess of the unemployment that exists at the natural level of employment.

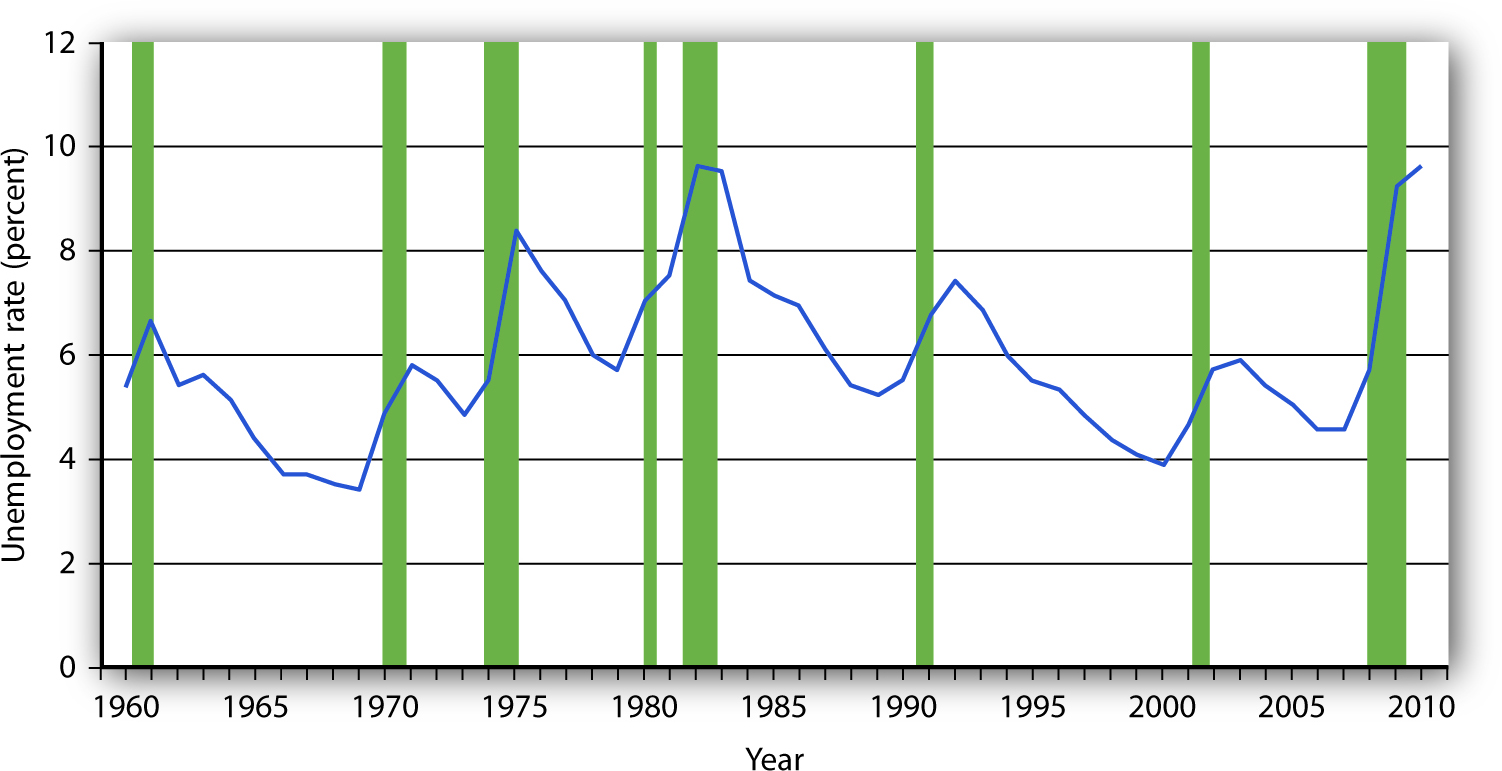

Figure 5.10 “Unemployment Rate, 1960–2010” shows the unemployment rate in the United States for the period from 1960 through November 2010. We see that it has fluctuated considerably. How much of it corresponds to the natural rate of unemployment varies over time with changing circumstances. For example, in a country with a demographic “bulge” of new entrants into the labour force, frictional unemployment is likely to be high, because it takes the new entrants some time to find their first jobs. This factor alone would raise the natural rate of unemployment. A demographic shift toward more mature workers would lower the natural rate. During recessions, highlighted in Figure 5.10 “Unemployment Rate, 1960–2010”, the part of unemployment that is cyclical unemployment grows. The analysis of fluctuations in the unemployment rate, and the government’s responses to them, will occupy center stage in much of the remainder of this book.

Figure 5.10 Unemployment Rate in the US, 1960–2010

The chart shows the unemployment rate for each year from 1960 to 2010. Recessions are shown as shaded areas.

Source: Economic Report of the President, 2010, Table B-42. Data for 2010 is average of first eleven months from the Bureau of Labor Statistics home page.

UNEMPLOYMENT RATES IN CANADA

Historical Unemployment Rates in Canada

Key Takeaways

- People who are not working but are looking and available for work at any one time are considered unemployed. The unemployment rate is the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed.

- When the labor market is in equilibrium, employment is at the natural level and the unemployment rate equals the natural rate of unemployment.

- Even if employment is at the natural level, the economy will experience frictional and structural unemployment. Cyclical unemployment is unemployment in excess of that associated with the natural level of employment.

Try It!

Given the data in the table, compute the unemployment rate in Year 1 and in Year 2. Explain why, in this example, both the number of people employed and the unemployment rate increased.

| Year | Number employed (in millions) | Number unemployed (in millions) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 2 |

| 2 | 21 | 2.4 |

Canada lost nearly 2 million jobs in April amid COVID-19 crisis: Statistics Canada

CBC News · Posted: May 08, 2020 8:41 AM ET | Last Updated: May 8

Canada lost almost two million jobs during the month of April, a record high, as the impact of COVID-19 on the economy made itself known.

Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey data released Friday brings the total number of jobs lost during the crisis to more than three million.

The closure of non-essential services to slow the spread of COVID-19 has devastated the economy and forced businesses to shutter temporarily.

Statistics Canada says the unemployment rate soared to 13 per cent as the full force of the pandemic hit, compared with 7.8 per cent in March.

Economists on average had expected the loss of four million jobs and an unemployment rate of 18 per cent, according to financial markets data firm Refinitiv.

Douglas Porter, chief economist with BMO Economics, said those high projections could be tied to reports that more than seven million Canadians had applied for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB).

“The 5.2 percentage point rise in the jobless rate was considerably less than expected, and massively smaller than the 10.3 percentage point spike in the U.S. jobless rate,” he said in an emailed statement.

Since comparable data became available in 1976, the April unemployment rate was second-highest only to December 1982, when it reached 13.1 per cent.

“By most accounts, unemployment soared to over 25 per cent during the worst of the Great Depression, as high as 30 per cent by some measures,” said Porter.

The rapid decline in employment is unprecedented, Statistics Canada says. The decline since February (-15.7 per cent) outpaces previous financial crises, including the 1981-1982 recession, which resulted in a drop of -5.4 per cent over 17 months.

“Today’s job numbers start to complete the picture of just how devastating the COVID-19 crisis has been to the Canadian labour market,” said economist Brendon Bernard of job site Indeed Canada in an email.

“While April’s decline was a bit more modest than expected, that 6.4 per cent of all Canadian adults could lose employment in a single month is staggering.”

Fewer hours for many who are still working

Job losses are not the only way the COVID-19 crisis has impacted employment. In addition to those who are now out of work, the number of people who were employed but worked less than half their usual hours because of the pandemic increased by 2.5 million from February to April.

That means the cumulative effect of the economic shutdown — people both no longer employed or working far less — was a staggering 5.5 million as of the week of April 12.

All provinces have been hard hit by the crisis. Employment dropped in all provinces for the second month running, with losses of more than 10 per cent everywhere.

Quebec had the worst losses in April at -18.7 per cent, or 821,000 jobs.

Here are the jobless rates last month by province (numbers from the previous month in brackets):

- Newfoundland and Labrador 16.0 per cent (11.7).

- Prince Edward Island 10.8 (8.6).

- Nova Scotia 12.0 (9.0).

- New Brunswick 13.2 (8.8).

- Quebec 17.0 (8.1).

- Ontario 11.3 (7.6).

- Manitoba 11.4 (6.4).

- Saskatchewan 11.3 (7.3).

- Alberta 13.4 (8.7).

- British Columbia 11.5 (7.2).

As for Canada’s three territories, due to logistical challenges, Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey methodology is somewhat different there than in the rest of Canada, said Bernard.

“Employment rates in the territories haven’t been hit as hard as the rest of Canada. That said, Nunavut saw a noticeable drop in the share of the population with a job in April, a sign of how public health concerns and economic uncertainty have extended beyond just the pandemic’s hot spots.”

There is evidence to suggest, however, that many pandemic-related job losses are temporary.

In the month of April, almost all of the newly unemployed — 97 per cent — were on temporary layoff, indicating they expect to return to their previous places of work as the shutdown is relaxed.

At the same time, workplace participation declined to 3.7 percentage points, bringing Canada’s participation rate to 59.8 per cent, as more than 1 million dropped out of the labour force, said Porter.

Among those still employed, the Labour Force Survey found that an additional 3.3 million workers were working from home in April.

Vulnerable workers most affected

Losses continued to be more rapid in jobs with less security and poorer pay.

Over the two-month period since February, overall employment (not adjusted for seasonality) declined 17.8 per cent.

But it was above average among employees with temporary jobs (-30.2 per cent) and those who had been in their jobs one year or less (-29.5 per cent).

Declines were sharper for employees earning less than two-thirds of the median hourly wage of $25.04 (-38.1 per cent) and those paid by the hour (-25.1 per cent).

Statistics Canada said this is consistent with job declines observed in accommodation and food services, and wholesale and retail trade, which tend to be more precarious and lower paying.

The number of people age 15 and older living households where no one is employed increased 23.5 per cent — or more than 1.6 million — in the two months between February and April.

Among couples, the number where neither partner is employed increased by 22.5 per cent, or 845,000, while single parents who are not employed increased by 53.9 per cent, or 126,000.

Small companies hardest hit

Smaller companies — defined as those with fewer than 20 employees — have shed 30.8 per cent of their workers, medium-sized firms have let 25.1 per cent of workers go, and large companies have seen employment decline by 12.6 per cent.

Hard-hit sectors at the outset include retail, hotels, restaurants and bars, which continued to see losses in April. The losses in the service sector also continued in April, down 1.4 million, or 9.6 per cent, Statistics Canada says.

Proportionally, the losses were greater in goods-producing sectors like construction and manufacturing, which combined lost 621,000 jobs for a drop of 15.8 per cent after being virtually unchanged in March.

The federal government announced Friday it will extend its emergency wage-subsidy to the end of June. The program — which covers 75 per cent of employees’ pay, up to $847, to help employers keep their workers on the payroll for the duration of the COVID-19 crisis — was previously set to end June 6.

Average wages in April were up 10.8 per cent compared with a year ago. Economists say the increase is because a disproportionate share of job losses in low-paying positions has allowed the average wage to rise.

“At the same time, relatively more people remained employed in industries where work can be done from home, such as public administration and professional, scientific and technical services, two of the highest-paying industries,” the report says.

Answer to Try It! Problem

In Year 1 the total labour force includes 22 million workers, and so the unemployment rate is 2/22 = 9.1%. In Year 2 the total labour force numbers 23.4 million workers; therefore the unemployment rate is 2.4/23.4 = 10.3%. In this example, both the number of people employed and the unemployment rate rose, because more people (23.4 − 22 = 1.4 million) entered the labour force, of whom 1 million found jobs and 0.4 million were still looking for jobs.