Unit 53: Informative and Persuasive Presentations

Learning Objectives

After studying this unit, you will be able to:

- describe the functions of the speech to inform

- provide examples of four main types of speeches to inform

- understand how to structure and develop a speech to inform

- identify and demonstrate how to use six principles of persuasion

- describe similarities and differences between persuasion and motivation

- identify and demonstrate the effective use of five functions of speaking to persuade

Introduction

Regardless of the type of presentation, you must prepare carefully. Are you trying to sell life insurance to a group of new clients, or presenting a proposal to secure financing to expand your business operation? Are you presenting the monthly update on the different sales divisions in your company, or providing customers with information on how to upgrade their latest computer purchase. Your future career will require you to present both to inform or to persuade. Knowing the difference between these two types of presentations and knowing how to construct each type of presentation will be beneficial to your future careers.

Presenting to Inform

At some point in your business career, you will be called upon to teach someone something. It may be a customer, coworker, or supervisor, and in each case, you are performing an informative speech. It is distinct from a sales speech, or persuasive speech, in that your goal is to communicate the information so that your listener understands. The informative speech is one performance you’ll give many times across your career, whether your audience is one person, a small group, or a large auditorium full of listeners. Once you master the art of the informative speech, you may mix and match it with other styles and techniques.

Functions

Informative presentations focus on helping the audience to understand a topic, issue, or technique more clearly. There are distinct functions inherent in a speech to inform, and you may choose to use one or more of these functions in your speech. Let’s take a look at the functions and see how they relate to the central objective of facilitating audience understanding.

Share: The basic definition of communication highlights the process of understanding and sharing meaning. An informative speech follows this definition when a speaker shares content and information with an audience. As part of a speech, you wouldn’t typically be asking the audience to respond or solve a problem. Instead, you’d be offering to share with the audience some of the information you have gathered related to a topic.

Increasing Understanding: How well does your audience grasp the information? This should be a guiding question to you on two levels. The first involves what they already know—or don’t know—about your topic, and what key terms or ideas might be necessary for someone completely unfamiliar with your topic to grasp the ideas you are presenting. The second involves your presentation and the illustration of ideas. The audience will respond to your attention statement and hopefully maintain interest, but how will you take your speech beyond superficial coverage of content and effectively communicate key relationships that increase understanding? These questions should serve as a challenge for your informative speech, and by looking at your speech from an audience-oriented perspective, you will increase your ability to increase the audience’s understanding.

Change Perceptions: How you perceive something has everything to do with a range of factors that are unique to you. We all want to make sense of our world, share our experiences, and learn that many people face the same challenges we do. For instance, many people perceive the process of speaking in public as a significant challenge, and in this text, we have broken down the process into several manageable steps. In so doing, we have to some degree changed your perception of public speaking.

When you present your speech to inform, you may want to change the audience member’s perceptions of your topic. You may present an informative speech on air pollution and want to change common perceptions such as the idea that most of North America’s air pollution comes from private cars. You won’t be asking people to go out and vote, or change their choice of automobiles, but you will help your audience change their perceptions of your topic.

Gain Skills: Just as you want to increase the audience’s understanding, you may want to help the audience members gain skills. If you are presenting a speech on how to make a meal from fresh ingredients, your audience may thank you for not only the knowledge of the key ingredients and their preparation but also the product available at the conclusion. If your audience members have never made their own meal, they may gain a new skill from your speech.

Exposition versus Interpretation: When you share information informally, you often provide your own perspective and attitude for your own reasons. The speech to inform the audience on a topic, idea, or area of content is not intended to be a display of attitude and opinion.

The speech to inform is like the classroom setting in that the goal is to inform, not to persuade, entertain, display attitude, or create comedy. If you have analyzed your audience, you’ll be better prepared to develop appropriate ways to gain their attention and inform them on your topic. You want to communicate thoughts, ideas, and relationships and allow each listener specifically, and the audience generally, to draw their own conclusions. The speech to inform is all about sharing information to meet the audience’s needs, not your own.

Exposition: Exposition means a public exhibition or display, often expressing a complex topic in a way that makes the relationships and content clear. The goal is to communicate the topic and content to your audience in ways that illustrate, explain, and reinforce the overall content to make your topic more accessible to the audience. The audience wants to learn about your topic and may have some knowledge of it as you do. It is your responsibility to consider ways to display the information effectively.

Interpretation and Bias: Interpretation involves adapting the information to communicate a message, perspective, or agenda. Your insights and attitudes will guide your selection of material, what you focus on, and what you delete (choosing what not to present to the audience). Your interpretation will involve personal bias.

Bias is an unreasoned or not-well-thought-out judgment. Bias involves beliefs or ideas held on the basis of conviction rather than current evidence. Beliefs are often called “habits of the mind” because we come to rely on them to make decisions. Which is the better, cheapest, most expensive, or the middle-priced product? People often choose the middle-priced product and use the belief “if it costs more it must be better” (and the opposite: “if it is cheap it must not be very good”). The middle-priced item, regardless of the actual price, is often perceived as “good enough.” All these perceptions are based on beliefs, and they may not apply to the given decision or even be based on any evidence or rational thinking.

We take mental shortcuts all day long, but in our speech to inform, we have to be careful not to reinforce bias.

Point of View: Clearly no one can be completely objective and remove themselves from their own perceptual process. People express themselves and naturally relate what is happening now to what has happened to them in the past. You are your own artist, but you also control your creations.

Objectivity involves expressions and perceptions of facts that are free from distortion by your prejudices, bias, feelings or interpretations. For example, is the post office box blue? An objective response would be yes or no, but a subjective response might sound like “Well, it’s not really blue as much as it is navy, even a bit of purple.” Subjectivity involves expressions or perceptions that are modified, altered, or impacted by your personal bias, experiences, and background. In an informative speech, your audience will expect you to present the information in a relatively objective form. The speech should meet the audience’s needs as they learn about the content, not your feelings, attitudes, or commentary on the content.

Knowledge Check

Types of Informative Presentations

Speaking to inform may fall into one of several categories. The presentation to inform may be an explanation, a report, a description, or a demonstration. Each type of informative speech is described below.

Explanation: Have you ever listened to a lecture or speech where you just didn’t get it? It wasn’t that you weren’t interested, at least not at first. Perhaps the presenter used language you didn’t understand or gave a confusing example. Soon you probably lost interest and sat there, attending the speech in body but certainly not in mind. An effective speech to inform will take a complex topic or issue and explain it to the audience in ways that increase audience understanding.

No one likes to feel left out. As the speaker, it’s your responsibility to ensure that this doesn’t happen. Also, know that to teach someone something new—perhaps a skill that they did not possess or a perspective that allows them to see new connections—is a real gift, both to you and the audience members. You will feel rewarded because you made a difference and they will perceive the gain in their own understanding.

Report: As a business communicator, you may be called upon to give an informative report where you communicate status, trends, or relationships that pertain to a specific topic. The informative report is a speech where you organize your information around key events, discoveries, or technical data and provide context and illustration for your audience. They may naturally wonder, “Why are sales up (or down)?” or “What is the product leader in your lineup?” and you need to anticipate their perspective and present the key information that relates to your topic.

Description: Have you ever listened to a friend tell you about their recent trip somewhere and found the details fascinating, making you want to travel there or visit a similar place? Describing information requires an emphasis on language that is vivid, captures attention, and excites the imagination. Your audience will be drawn to your effective use of color, descriptive language, and visual aids. An informative speech that focuses on the description will be visual in many ways. Use your imagination to place yourself in their perspective: how would you like to have someone describe the topic to you?

Demonstration: You want to teach the audience how to program the applications on a new smartphone. A demonstrative speech focuses on clearly showing a process and telling the audience important details about each step so that they can imitate, repeat, or do the action themselves. Consider the visual aids or supplies you will need.

By considering each step and focusing on how to simplify it, you can understand how the audience might grasp the new information and how you can best help them. Also, consider the desired outcome; for example, will your listeners be able to actually do the task themselves? Regardless of the sequence or pattern you will illustrate or demonstrate, consider how people from your anticipated audience will respond, and budget additional time for repetition and clarification.

Knowledge Check

Creating an Informative Presentation

An informational presentation is a common request in business and industry. It’s the verbal and visual equivalent of a written report. Informative presentations serve to present specific information for specific audiences for specific goals or functions. Table 53.1 below describes five main parts of a presentation to inform.

Table 53.1: Five Main Presentation Components and Their Functions (McLean, S., 2003)

|

Component |

Function |

|

Attention Statement |

Raise interest and motivate the listener |

|

Introduction |

Communicate a point and common ground |

|

Body |

Address key points |

|

Conclusion |

Summarize key points |

|

Residual Message |

Communicate central theme, moral of story, or main point |

Sample Speech Guidelines

Imagine that you have been assigned to give an informative presentation lasting five to seven minutes. Follow the guidelines in Table 53.2 below and apply them to your presentation.

Table 53.2: Seven Key Speech Guidelines

|

Topic |

Choose a product or service that interests you (if you have the option of choice) and report findings in your speech. Even if you are assigned a topic, find an aspect or angle that is of interest to research. |

|

Purpose |

Your general purpose, of course, is to inform. But you need to formulate a more specific purpose statement that expresses a point you have to make about your topic—what you hope to accomplish in your speech. |

|

Audience |

Think about what your audience might already know about your topic and what they may not know, and perhaps any attitudes toward or concerns about it. Consider how this may affect the way that you will present your information. |

|

Supporting Materials |

Using the information gathered in your search for information, determine what is most worthwhile, interesting, and important to include in your speech. Time limits will require that you be selective about what you use. Use visual aids! |

|

Organization |

|

|

Introduction |

Develop an opening that will

|

|

Conclusion |

The conclusion should review and/or summarize the important ideas in your speech and bring it to a smooth close. |

|

Delivery |

The speech should be delivered extemporaneously (not reading but speaking), using speaking notes and not reading from the manuscript. Work on maximum eye contact with your listeners. Use any visual aids or handouts that may be helpful. |

Informative presentations illustrate, explain, describe, and instruct the audience on topics and processes. Now let’s watch an example of an informative speech.

The Persuasive Presentation

No doubt there has been a time when you wanted to achieve a goal or convince someone about a need and you thought about how you were going to present your request. Consider how often people want something from you? When you watch television, advertisements reach out for your attention, whether you watch them or not. When you use the internet, pop-up advertisements often appear. Most people are surrounded, even inundated by persuasive messages. Mass and social media in the 21st century have had a significant effect on persuasive communication that you will certainly recognize.

Persuasion is an act or process of presenting arguments to move, motivate, or change the mind of your audience. Persuasion can be implicit or explicit and can have both positive and negative effects. Motivation is different from persuasion in that it involves the force, stimulus, or influence to bring about change. Persuasion is the process, and motivation is the compelling stimulus that encourages your audience to change their beliefs or behaviour, to adopt your position, or to consider your arguments. Let’s view the video below for an overview of the principles of a persuasive presentation.

Principles of Persuasion

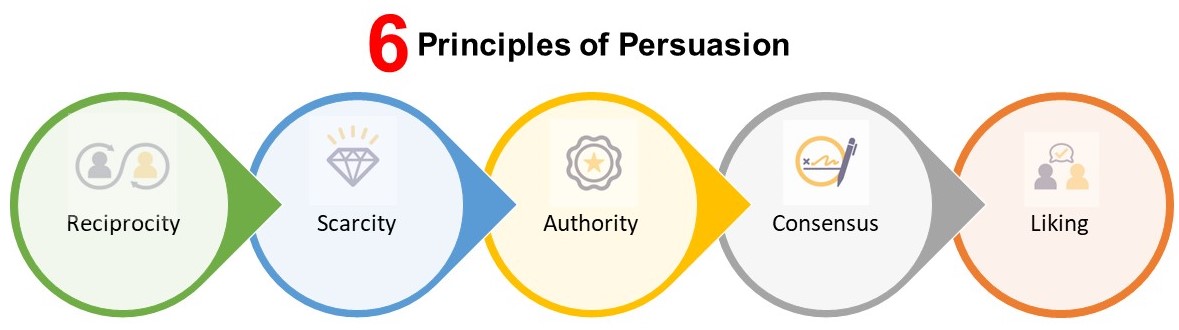

What is the best way to succeed in persuading your listeners? There is no one “correct” answer, but many experts have studied persuasion and observed what works and what doesn’t. Social psychologist Robert Cialdini (2006) offers us six principles of persuasion that are powerful and effective: Reciprocity, Scarcity, Authority, Commitment and consistency, Consensus, and Liking. These six principles are covered in more detail in Unit 41.

Developing a Persuasive Presentation

Persuasive presentations:

Stimulate

When you focus on stimulation as the goal of your speech, you want to reinforce existing beliefs, intensify them, and bring them to the forefront. By presenting facts, you will reinforce existing beliefs, intensify them, and bring the issue to the surface. You might consider the foundation of common ground and commonly held beliefs, and then introduce information that a mainstream audience may not be aware of that supports that common ground as a strategy to stimulate.

Convince

In a persuasive speech, the goal is to change the attitudes, beliefs, values, or judgments of your audience. Audience members are likely to hold their own beliefs and are likely to have their own personal bias. Your goal is to get them to agree with your position, so you will need to plan a range of points and examples to get audience members to consider your topic. Here is a five-step checklist to motivate your audience into some form of action:

1. Get their attention

2. Identify the need

3. Satisfy the need

4. Present a vision or solution

5. Take action

This simple organizational pattern can help you focus on the basic elements of a persuasive message that will motivate your audience to take action…

Include a Call to Action

When you call an audience to action with a speech, you are indicating that your purpose is not to stimulate interest, reinforce and accentuate beliefs, or convince them of a viewpoint. Instead, you want your listeners to do something, to change their behaviour in some way. The persuasive speech that focuses on action often generates curiosity, clarifies a problem, and as we have seen, proposes a range of solutions. The key difference here is there is a clear link to action associated with the solutions.

Solutions lead us to consider the goals of action. These goals address the question, “What do I want the audience to do as a result of being engaged by my speech?” The goals of action include adoption, discontinuance, deterrence, and continuance.

Adoption means the speaker wants to persuade the audience to take on a new way of thinking, or adopt a new idea. Examples could include buying a new product, or deciding to donate blood. The key is that the audience member adopts, or takes on, a new view, action, or habit.

Discontinuance involves the speaker persuading the audience to stop doing something that they have been doing. Rather than take on a new habit or action, the speaker is asking the audience member to stop an existing behaviour or idea.

Deterrence is a call to action that focuses on persuading the audience not to start something if they haven’t already started. The goal of action would be to deter, or encourage the audience members to refrain from starting or initiating the behavior.

Finally, with Continuance, the speaker aims to persuade the audience to continue doing what they have been doing, such as keep buying a product, or staying in school to get an education.

A speaker may choose to address more than one of these goals of action, depending on the audience analysis. If the audience is largely agreeable and supportive, you may find continuance to be one goal, while adoption is secondary.

Goals in call to action speeches serve to guide you in the development of solution steps. Solution steps involve suggestions or ways the audience can take action after your speech. Audience members appreciate a clear discussion of the problem in a persuasive speech, but they also appreciate solutions.

Increase Consideration

In a speech designed to increase consideration, you want to entice your audience to consider alternate viewpoints on the topic you have chosen. Audience members may hold views that are hostile in relation to yours, or perhaps they are neutral and simply curious about your topic. You won’t be asking for action in this presentation, simply to consider an alternative perspective.

Develop Tolerance of Alternate Perspectives

Finally, you may want to help your audience develop tolerance for alternate perspectives and viewpoints. Your goal is to help your audience develop tolerance, but not necessarily acceptance, of alternate perspectives. By starting from common ground, and introducing a related idea, you are persuading your audience to consider an alternate perspective.

A persuasive speech may stimulate thought, convince, call to action, increase consideration, or develop tolerance of alternate perspectives. Watch the following video of a persuasive speech with annotation to see the concepts above in action.

Knowledge Check

Persuasive Strategies

When you make an argument in a persuasive speech, you will want to present your position logically by supporting each point with appropriate sources. You will want to give your audience every reason to perceive you as an ethical and trustworthy speaker. Your audience will expect you to treat them with respect, and to present your argument in a way that does not make them defensive. Contribute to your credibility by building sound arguments and using strategic arguments with skill and planning.

Stephen Toulmin’s (1958) rhetorical strategy focuses on three main elements, shown in Table 53.3 as a claim, data, and warrant.

Table 53.3 Rhetorical strategy

|

Element |

Description |

Example |

|

Claim |

Your statement of belief or truth |

It is important to spay or neuter your pet. |

|

Data |

Your supporting reasons for the claim |

Millions of unwanted pets are euthanized annually. |

|

Warrant |

You create the connection between the claim and the supporting reasons |

Pets that are spayed or neutered do not reproduce, preventing the production of unwanted animals. |

This three-part rhetorical strategy is useful in that it makes the claim explicit, clearly illustrating the relationship between the claim and the data, and allows the listener to follow the speaker’s reasoning. You may have a good idea or point, but your audience will be curious and want to know how you arrived at that claim or viewpoint. The warrant often addresses the inherent and often unspoken question, “Why is this data so important to your topic?” and helps you illustrate relationships between information for your audience. This model can help you clearly articulate it for your audience.

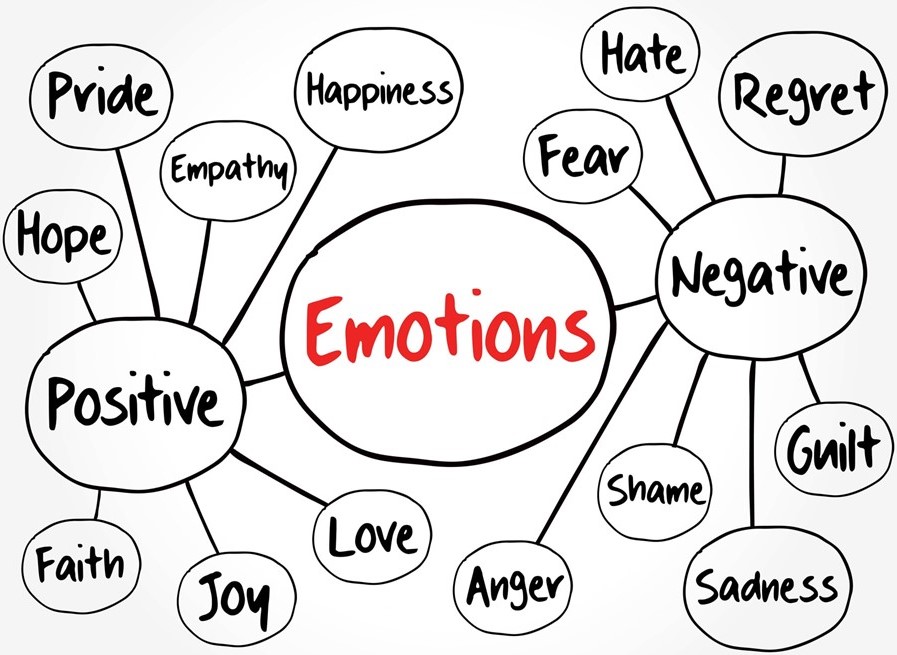

Appealing to Emotions

Emotions are psychological and physical reactions, such as fear or anger, to stimuli that we experience as a feeling. Our feelings or emotions directly impact our own point of view and readiness to communicate, but also influence how, why, and when we say things. Emotions influence not only how you say what you say, but also how you hear and what you hear. At times, emotions can be challenging to control. Emotions will move your audience, and possibly even move you, to change or act in certain ways.

Be wary of overusing emotional appeals, or misusing emotional manipulation in presentations and communication. You may encounter emotional resistance from your audience. Emotional resistance involves getting tired, often to the point of rejection, of hearing messages that attempt to elicit an emotional response. Emotional appeals can wear out the audience’s capacity to receive the message.

The use of an emotional appeal may also impair your ability to write persuasively or effectively. Never use a personal story, or even a story of someone you do not know if the inclusion of that story causes you to lose control. While it’s important to discuss relevant and sometimes emotionally difficult topics, you need to assess your own relationship to the message. Your documents should not be an exercise in therapy and you will sacrifice ethos and credibility, even your effectiveness, if you become angry or distraught because you are really not ready to discuss an issue you’ve selected.

Now that you’ve considered emotions and their role in a speech in general and a speech to persuade specifically, it’s important to recognize the principles about emotions in communication that serve you well when speaking in public. The video below reviews how to effectively integrate emotion, logic and credibility into your presentation.

Knowledge Check

DeVito (2003) offers five key principles to acknowledge the role emotions play in communication and offer guidelines for there expression.

Emotions Are Universal: Emotions are a part of every conversation or interaction that you have. Whether or not you consciously experience them while communicating with yourself or others, they influence how you communicate. By recognizing that emotions are a component in all communication interactions, you can place emphasis on understanding both the content of the message and the emotions that influence how, why, and when the content is communicated.

Expression of emotions is important, but requires the three Ts: tact, timing, and trust. If you find you are upset and at risk of being less than diplomatic, or the timing is not right, or you are unsure about the level of trust, then consider whether you can effectively communicate your emotions. By considering these three Ts, you can help yourself express your emotions more effectively.

Emotions Are Communicated Verbally and Nonverbally: You communicate emotions not only through your choice of words but also through the manner in which you say those words. The words themselves communicate part of your message, but the nonverbal cues, including inflection, timing, space, and paralanguage can modify or contradict your spoken message. Be aware that emotions are expressed in both ways and pay attention to how verbal and nonverbal messages reinforce and complement each other.

Emotional Expression Can Be Good and Bad: Expressing emotions can be a healthy activity for a relationship and build trust. It can also break down trust if expression is not combined with judgment. We’re all different, and we all experience emotions, but how we express our emotions to ourselves and others can have a significant impact on our relationships. Expressing frustrations may help the audience realize your point of view and see things as they have never seen them before. However, expressing frustrations combined with blaming can generate defensiveness and decrease effective listening. When you’re expressing yourself, consider the audience’s point of view, be specific about your concerns, and emphasize that your relationship with your listeners is important to you.

Emotions Are Often Contagious: It is important to recognize that we influence each other with our emotions, positively and negatively. Your emotions as the speaker can be contagious, so use your enthusiasm to raise the level of interest in your topic. Conversely, you may be subject to “catching” emotions from your audience.

In summary, everyone experiences emotions, and as a persuasive speaker, you can choose how to express emotion and appeal to the audience’s emotions.

Presenting Ethically

What comes to mind when you think of speaking to persuade? Perhaps the idea of persuasion may bring to mind propaganda and issues of manipulation, deception, intentional bias, bribery, and even coercion. Each element relates to persuasion, but in distinct ways. We can recognize that each of these elements in some ways has a negative connotation associated with it. Why do you think that deceiving your audience, bribing a judge, or coercing people to do something against their wishes is wrong? These tactics violate our sense of fairness, freedom, and ethics.

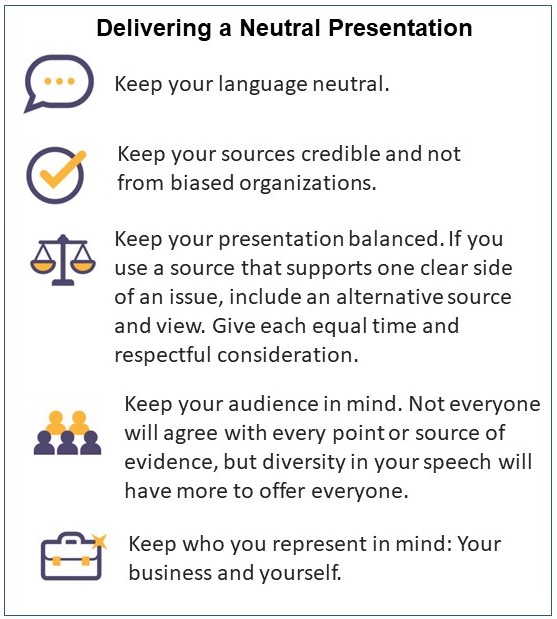

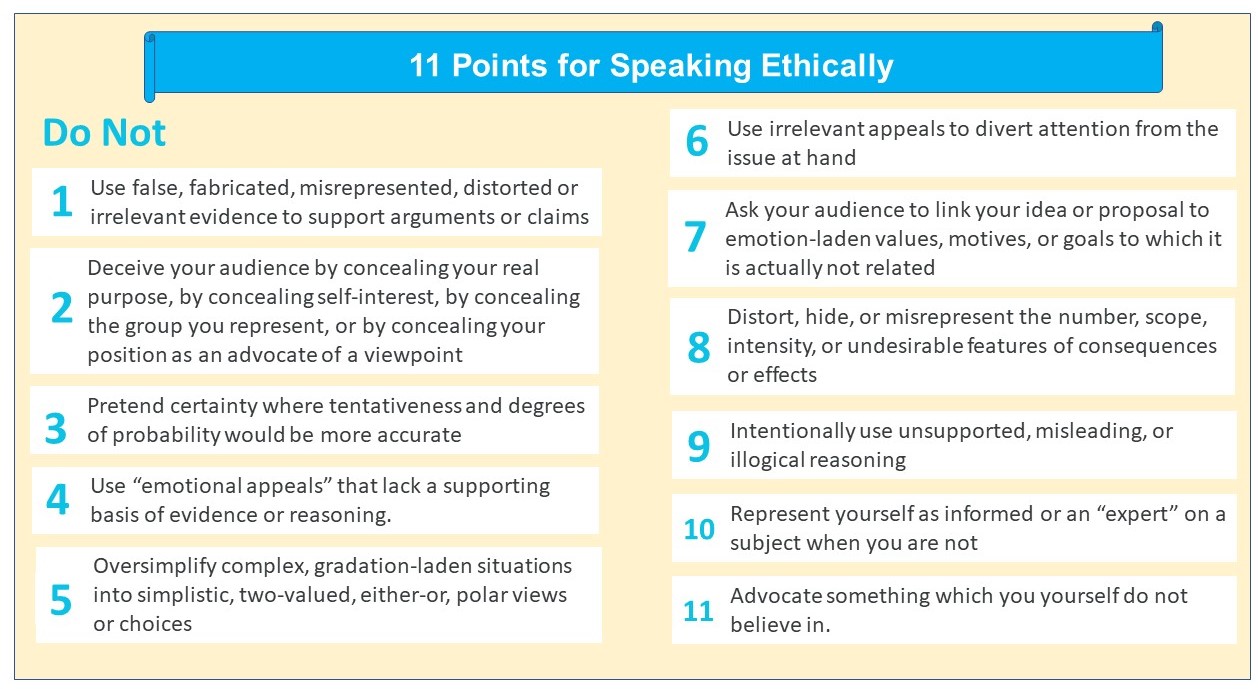

Figure 53.4 offers eleven points from the book Ethics in Human Communication (Johannesen, 1996). These points should be kept in mind as you prepare and present your persuasive message.

In your speech to persuade, consider honesty and integrity as you assemble your arguments. Your audience will appreciate your thoughtful consideration of more than one view, your understanding of the complexity, and you will build your ethos, or credibility, as you present your document. Be careful not to stretch the facts, or assemble them only to prove yourself, and instead prove the argument on its own merits. Deception, coercion, intentional bias, manipulation and bribery should have no place in your speech to persuade.

Knowledge Check

References

Comm Studies. (2019). Informative speech example [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=StPSgqwCnVk&t=60s

eCampusOntario. (2020). Chapter 7: Presentation to inform. Communication for business professionals. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/commbusprofcdn/chapter/introduction-5/

eCampusOntario. (2020). Chapter 8: Presentation to persuade. Communication for business professionals. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/commbusprofcdn/chapter/introduction-6/

Guffey, M., Loewry, D., & Griffin, E. (2019). Business communication: Process and product (6th ed.). Toronto, ON: Nelson Education. Retrieved from http://www.cengage.com/cgi-wadsworth/course_products_wp.pl?fid=M20b&product_isbn_issn=9780176531393&template=NELSON

Littleleague.org. (2020). “Calm” emotions & “positive” feelings: Two keys to stay healthy during self-Isolation. Resources for parents. Retrieved from https://www.littleleague.org/news/calm-emotions-positive-feelings-two-keys-to-stay-healthy-during-self-isolation/

Lyon, A. (2017). Ethos Pathos Logos [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ey232I5nUk

Lyon, A. (2017). How to Organize a Persuasive Speech or Presentation [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jnfoFN7TBhw

Lyon, A. (2019). Informative vs persuasive [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=85gg_pgij4I

Reciprocity is the mutual expectation for exchange of value or service.

You want what you can’t have, and it’s universal. People are often attracted to the exclusive, the rare, the unusual, and the unique

Trust is central to the purchase decision

People like to have consistency in what is said to them or in writing. Therefore, it is important that all commitments made are honored at all times.

People often look to each other when making a purchase decision, and the herd mentality is a powerful force across humanity

We tend to be attracted to people who communicate to us that they like us, and who make us feel good about ourselves. This principle involves the perception of safety and belonging in communication.

management of facts, ideas or points of view to play upon inherent insecurities or emotional appeals to one’s own advantage

use of lies, partial truths, or the omission of relevant information to deceive your audience

the selection of information to support your position while framing negatively any information that might challenge your belief

giving of something in return for an expected favour, consideration, or privilege

use of power to compel action